How an East Village building went from gangster hangout to Andy Warhol’s Electric Circus

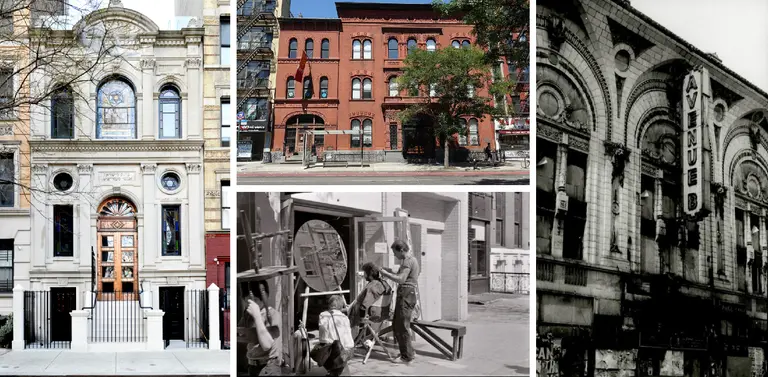

Google Street View of 19-25 St. Mark’s Place today

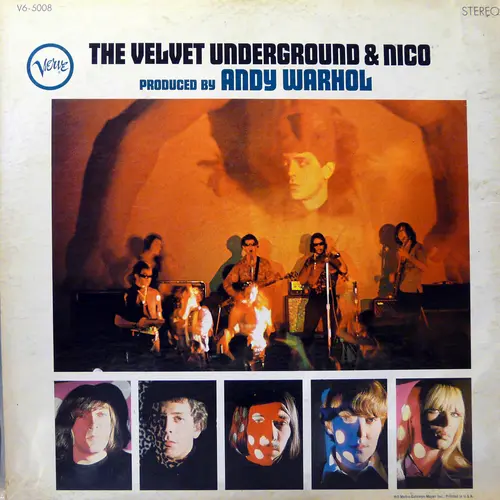

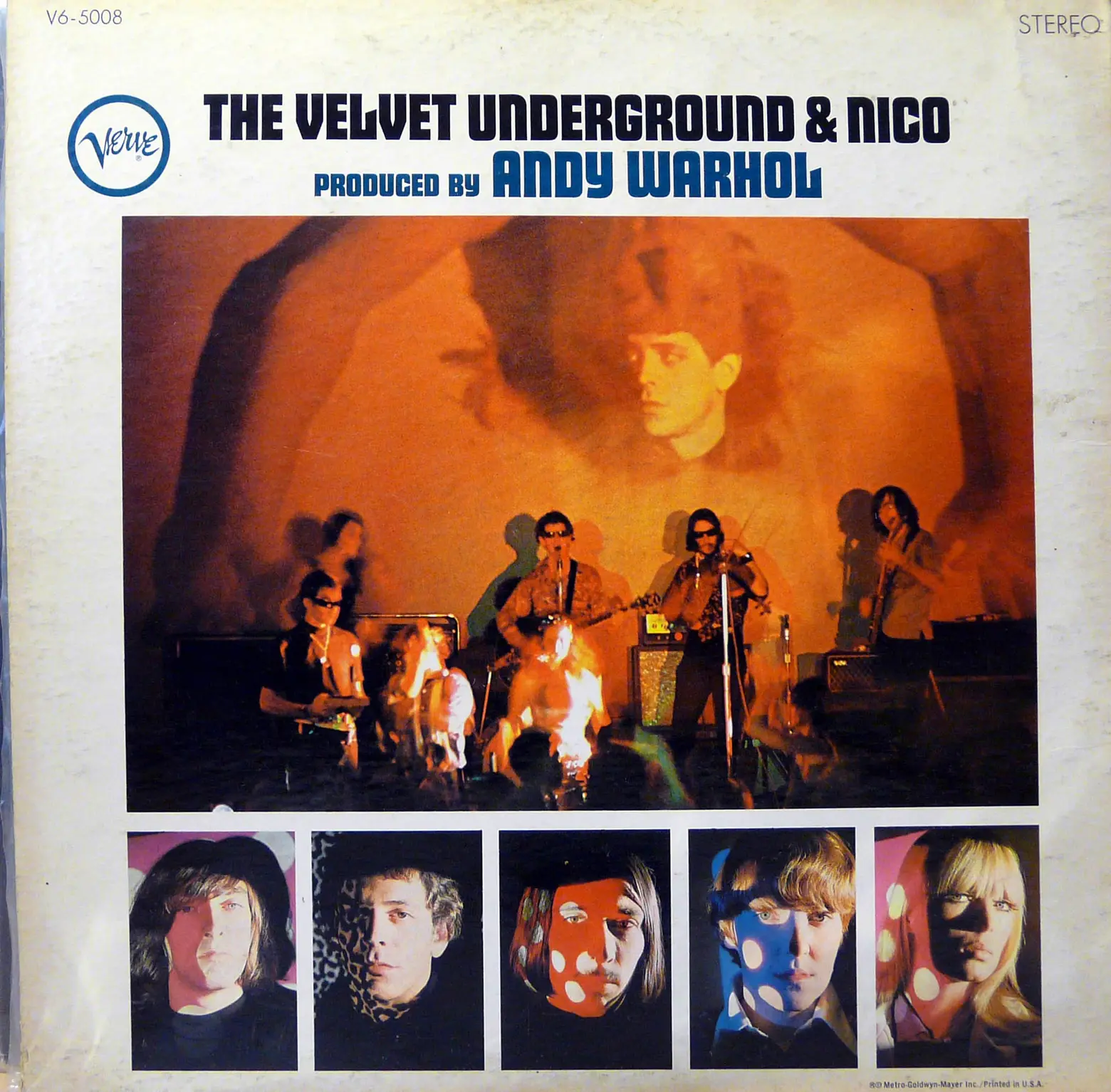

Fifty years ago this week, the Velvet Underground released their second album, “White Light/White Heat.” Their darkest record, it was also arguably the Velvet’s most influential, inspiring a generation of alternative musicians with the noisy, distorted sound with which the band came to be so closely identified.

Perhaps the place with which the Velvets have come to be most closely identified is the Electric Circus, the Andy Warhol-run East Village discotheque where they performed as the house band as part of a multi-media experience known as the “Exploding Plastic Inevitable.” Many New Yorkers would be surprised to discover that the space the club once occupied at 19-25 St. Mark’s Place has since been home to a Chipotle and a Supercuts. But the history of the building that launched the career of the godfathers of punk is full of more twists, turns, and ups and downs than one the Velvet’s extended distorted jams that once reverberated within its walls.

20 St. Mark’s Place, via GVSHP

20 St. Mark’s Place, via GVSHP

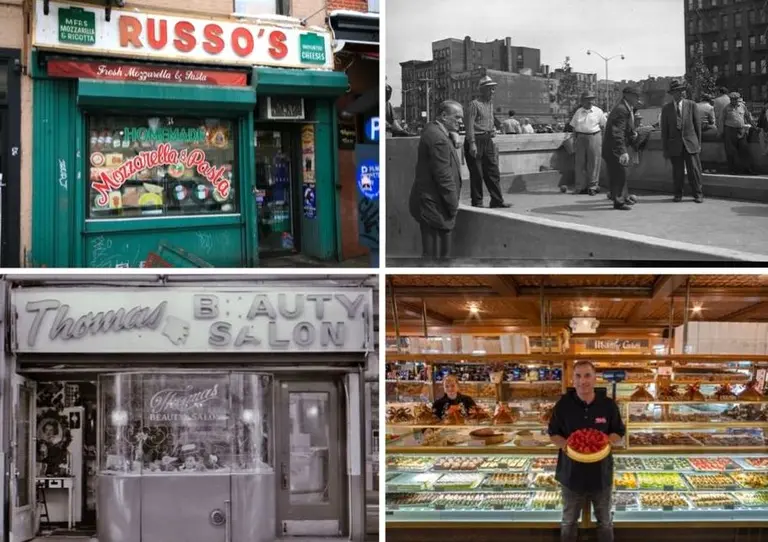

19 through 25 St. Mark’s Place were originally built as four separate rowhouses around 1833 by renowned developer Thomas E. Davis. Davis also built 4 St. Mark’s Place (the former home of Trash and Vaudeville), 20 St. Mark’s Place (the former home of Sounds Records), and the two houses that lie underneath the metallic façade of the Ukrainian National Home just around the corner at 140-142 Second Avenue (a building with its own twisting ethnic and musical history). The houses at 19 to 25 probably originally looked very much like its surviving neighbors at numbers 4 and 20. When these houses were built, St. Mark’s Place was one of the most fashionable addresses in New York City, and they would have been occupied by some of the city’s most well-heeled residents.

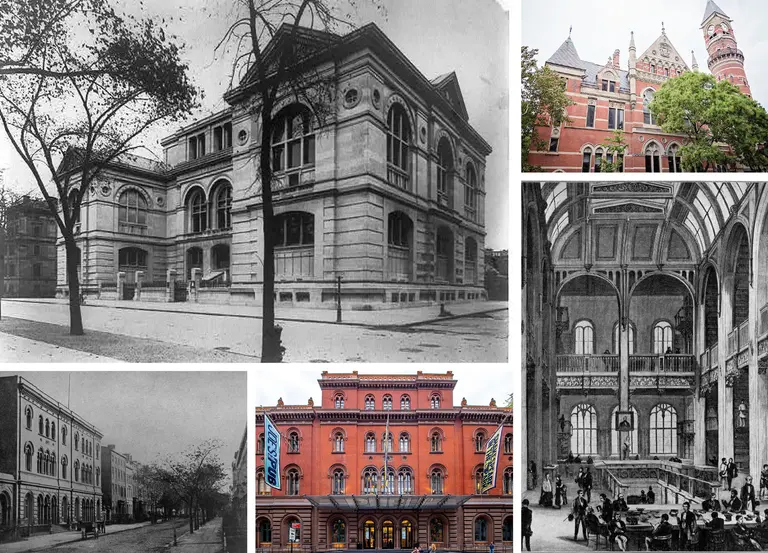

But what we today call the East Village did not stay fashionable for long. Massive immigration in the mid-19th century, especially from revolution-wracked Germany, meant by 1850 many of these homes were converted into boarding houses. By 1870 the buildings had been acquired by the Arion Society, a singing and music club that was one of many German organizations to set down roots in the vicinity, such as the Deutsche-Amerikanische Shutzen Gesellschaft (German-American Shooting Society) across the street at 12 St. Mark’s Place, or the former Ottendorfer Library and German Dispensary around the corner at 135-137 Second Avenue. The takeover of the buildings by the Arion Society appears to have been the beginning of their physical transformation as well, with an elaborate mansard roof added on top at this time.

Arlington Hall c. 1892, via Wiki Commons

Arlington Hall c. 1892, via Wiki Commons

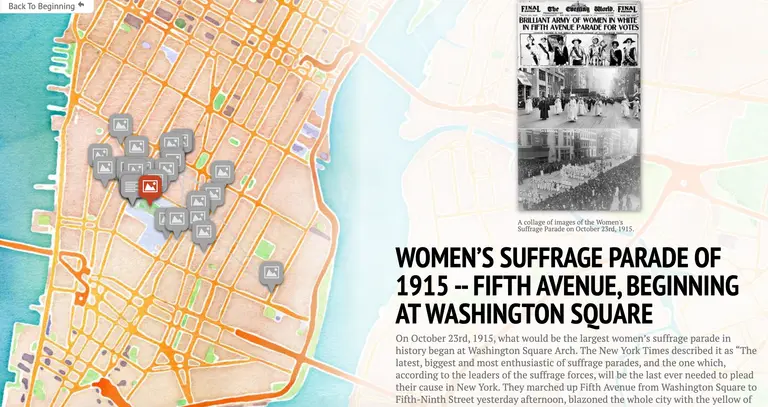

By 1887, the Arion Society had moved uptown, as did many German-Americans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The space became Arlington Hall, a ballroom and community hall that hosted weddings, dances, political rallies, and union meetings, often for the burgeoning Jewish and Italian immigrant population in the neighborhood. Everyone from New York City Police Commissioner Teddy Roosevelt to newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst attended events there.

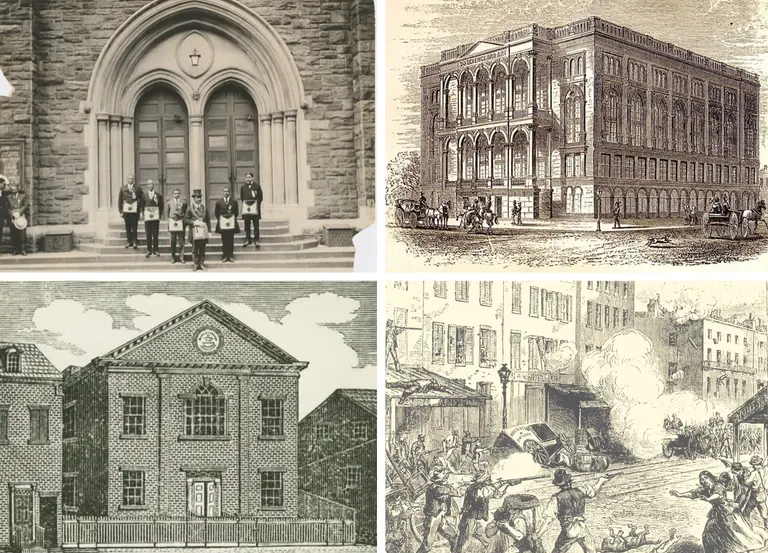

But Arlington Hall also attracted some less savory characters. In 1914, a fatal shootout between bitter rival gangs lead by Benjamin “Dopey Benny” Fein and Jack Sirocco lasting several hours took place inside the hall and spilled out onto the streets. While neither Fein nor Sirocco were injured in the gun battle, Sirocco disappeared from New York shortly thereafter, and Fein was arrested for the murder of court clerk Frederick Strauss, who was killed in the crossfire between the two gangs. “Dopey Benny” Fein, so named because of his perpetually half-closed eyes, was released when no witnesses would identify him.

By the 1920s, Poles and Ukrainians added to the heady immigrant mix on St. Mark’s Place. At this time, the buildings were acquired by the Polish National Home, or Polski Dom Nardowy, with a restaurant and meeting hall downstairs and space for Polish organizations above, not unlike the Ukrainian National Home still operating around the corner.

By the 1950s, the space was attracting an increasingly Beatnik crowd. The migration of the Beats, artists, writers, and other bohemians east to St. Marks Place and the rest of the East Village was accelerated by the dismantling of the Third Avenue Elevated in 1955, which had run along the west side of this block, separating it from Greenwich Village.

Out of the Polish National Home came a restaurant and bar in the downstairs space known as “The Dom,” from the Polish for “home,” where seminal 60s bands like The Fugs played.

But without a doubt, the space reached its zenith of hipness in 1966 when Andy Warhol and filmmaker Paul Morrissey took it over to create a discotheque called The Electric Circus. The club featured a multimedia experience called the “Exploding Plastic Inevitable” that merged music, projected lightshows, trapeze artists, mimes, jugglers, fire-eaters, and dancing in a space designed to look like a surreal Moroccan tent. It was here that the Velvet Underground performed nightly as the House band and were first exposed to a larger downtown audience before recording their first album with Nico in early 1967.

The Velvets were not the only band to get their start here; Sly and the Family Stone, the Allman Brothers, Deep Purple, and the Chambers Brothers, among many others, staged early performances here, attended by the likes of Tom Wolfe and George Plimpton.

But like so many of the transformative moments of the 1960s, this one was short-lived. A darker cloud descended over the neighborhood, as violence, drugs, and crime replaced the utopian aspirations. In March of 1970, a bomb went off on the dance floor of the Electric Circus, purportedly set by the Black Panthers. Though never proven, it was enough to tarnish the club’s image and keep patrons away. It finally closed its doors in 1971.

By the 1980s, the building had been taken over by a social service agency called the All Craft Center, which offered services and counseling to clients with drug and alcohol problems. The buildings were painted a bleak blue and white and often covered in graffiti. The Center and its leader, the Rev. Joyce Hartwell, were the subject of some controversy for the loose management of the sprawling social service facility and the scores of clients who regularly camped out in front of the buildings on St. Marks Place. A never-realized plan to build a 176-room hotel in the rear of the buildings as a source of revenue also elicited pushback from neighbors.

But during this period the buildings remained in much the same condition, at least on the outside, as they did after their first renovation in 1870. Even the mansard roof remained intact, if it like the rest of the buildings were now frequently covered in a grim coat of graffiti and paint. A peculiar moment in the buildings’ history came in 1986 when they were featured in the video for Billy Joel’s platitudinous top 40 hit “A Matter of Trust,” in which Joel and his band perform in the old Dom space with the windows wide open, inviting the neighborhood in to listen. The video, above, captures a surprisingly clear picture of the buildings and St. Marks Place at the time, albeit scrubbed clean and on its best behavior for the video shoot.

By the early 2000s, however, the All Craft Center was no more, and the buildings were sold to a developer. The exterior of 19-25 St. Marks Place was entirely refaced, and stores, including the aforementioned Chipotle and Supercuts, went into the former Dom and Electric Circus spaces. The 1870 mansard roof was removed and a large multi-story penthouse addition was added above.

The buildings are now almost unrecognizable from their prior incarnations as gangster hangout or pop art performance venue. Believing the twisting nearly 200-year history behind the recently added façade is, at this point, just a matter of trust.

+++

RELATED:

- Jewish gangsters, jazz legends, and Joy Division: The evolution of the Ukrainian National Home

- The long cultural and musical history of Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Lady Studios in Greenwich Village

- Iconic album covers of Greenwich Village and the East Village: Then and now

This post comes from the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Since 1980, GVSHP has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid.

Via

Via