Jewish gangsters, jazz legends, and Joy Division: The evolution of the Ukrainian National Home

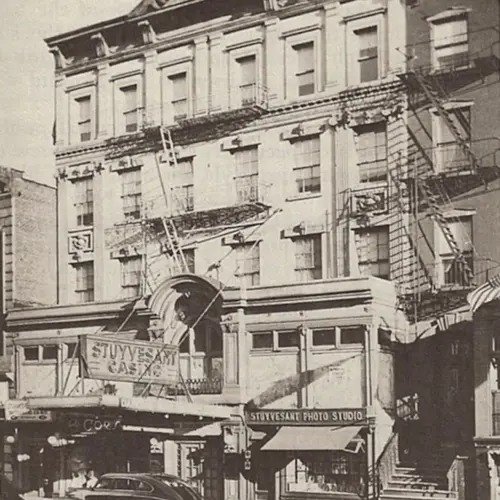

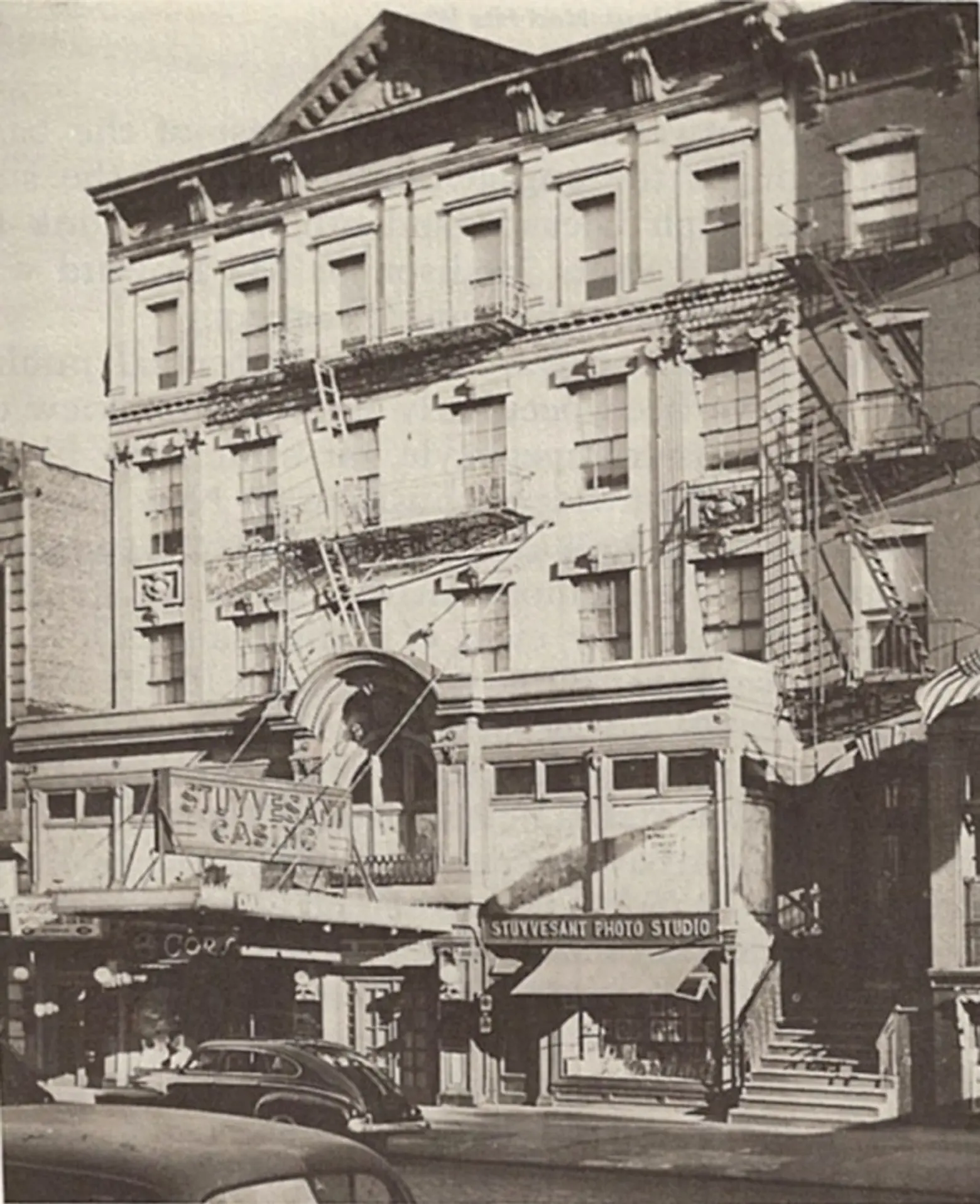

The Stuyvesant Casino in 1945, via the Swedish Buck Johnson Society (L); The Ukrainian National Home Today, via Wally Gobetz/Flickr (R)

On 2nd Avenue, just south of 9th Street at No. 140-142, sits one of the East Village’s oddest structures. Clad in metal and adorned with Cyrillic lettering, the building sports a slightly downtrodden and forbidding look, seeming dropped into the neighborhood from some dystopian sci-fi thriller.

In reality, for the last half century the building has housed the Ukrainian National Home, best known as a great place to get some good food or drink. But scratch the surface of this architectural oddity and you’ll find a winding history replete with Jewish gangsters, German teetotalers, jazz-playing hipsters, and the American debut of one of Britain’s premier post-punk bands, all in a building which, under its metallic veneer, dates back nearly two centuries.

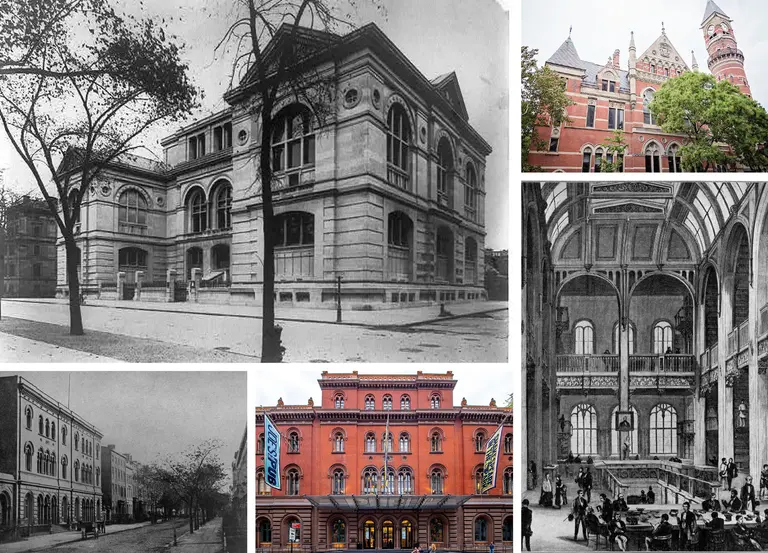

138 Second Avenue with 140-142 to its left, via HDC/Six to Celebrate

138 Second Avenue with 140-142 to its left, via HDC/Six to Celebrate

The exact date of construction of 140-142 Second Avenue is not known, but evidence indicates it was built around 1830. Then one of New York’s most fashionable streets, this stretch of Second Avenue had been part of Peter Stuyvesant’s farm, which after his death was divided among his heirs. In the early 1830s, urban development reached this area, and stately federal-style single-family homes were built for successful merchants along this street and nearby St. Mark’s Place. 140-142 Second Avenue was probably first constructed at this time as two such houses, which likely looked very much like nearby 4 St. Marks Place. It also probably looked a lot like its neighbor to the south, 138 Second Avenue, before it had a full fourth floor added in the late 19th century and a two-story commercial addition in front in the early 20th century.

The first big change to hit 140-142 Second Avenue in its evolution from single-family rowhouse to its present form was the immigration of huge numbers of Germans to New York in the mid-19th century, largely settling in today’s East Village. The area came to be known as Kleindeutschland or “Little Germany,” the largest settlement of Germans outside Berlin and Vienna. Second Avenue was its main street.

In 1881, in the heart of this thriving German community, the German Young Men’s Christian Association bought 140-142 Second Avenue and opened the largest such center in the area. The German YMCA was considered a moral cornerstone of this boisterous immigrant community, which was known for its fondness for beer and other drink. But alcohol was typically banned from gatherings at the German YMCA, which presented itself as an alternative to the countless and popular bars, saloons, and social halls found throughout the neighborhood.

But within just a couple of short decades of the Y’s founding, the neighborhood was changing again. The 1904 General Slocum ferry disaster, which killed more than 1,000 residents of this neighborhood, devastated the German-American community of Kleindeutschland. World War I’s anti-German fervor drove many of the few remaining German-Americans away from communities associated with their brethren. A new wave of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, largely Jewish, began to flood into this neighborhood, displacing the second- and third-generation German-Americans who now had the means to move to less crowded areas of the city such as Yorkville, Bushwick, and Maspeth, Queens.

It was at this time that this part of the Lower East Side became the center of Jewish life in America, and one of the most crowded, culturally vibrant, and also crime-ridden neighborhoods in New York. Second Avenue was the center of much of this activity, as it transformed from the main street of Kleindeutschland to the center of the Yiddish Rialto, a street bustling with theaters, cafes, nickelodeons, bars, and vaudeville houses, to which average New Yorkers and more than few mobsters were drawn.

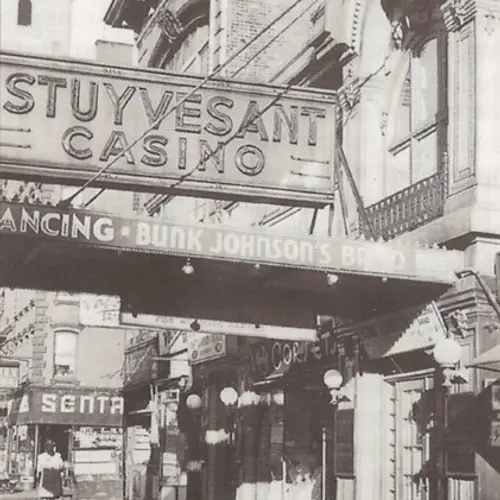

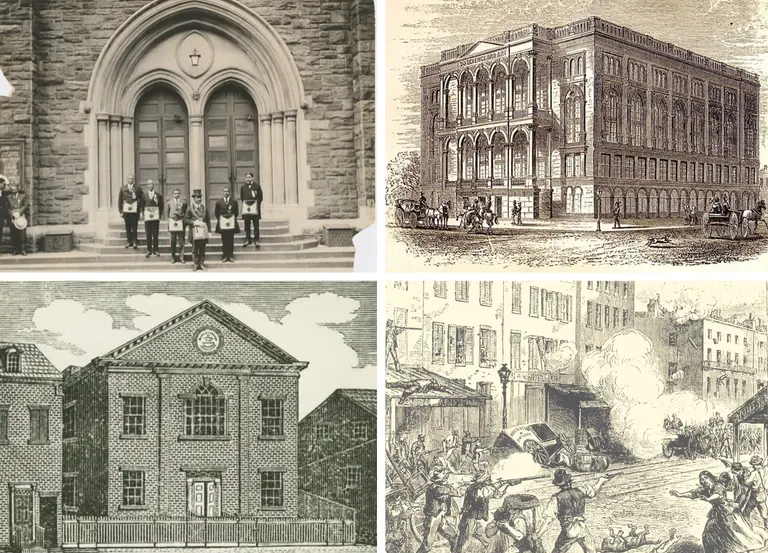

The Stuyvesant Casino in 1945, via the Swedish Buck Johnson Society

The Stuyvesant Casino in 1945, via the Swedish Buck Johnson Society

Reflecting these changes, by 1909 the very straitlaced German YMCA was gone from 140-142 Second Avenue, replaced by the decidedly more secular and profane Stuyvesant Casino. It’s likely that it was at this time that the two federal houses that survived on this spot got a newly unified facade, full fourth floor, and the two-story commercial extension along Second Avenue, which was so common for buildings in this bustling entertainment district, bursting at its seams to try to accommodate all the activity.

From the beginning, the Casino attracted a broad cross-section of the neighborhood’s population looking for a place to congregate and celebrate. And while some of those occasions may have been more wholesome, such as a reception for returning Jewish World War I veterans in 1919, some were decidedly less so.

The Casino’s earliest and most enduring brush with infamy came in 1911 when notorious Lower East Side gangster “Big” Jack Zelig (born Zelig Harry Lefkowitz in 1888, also known as “The Big Yid”), leader of the feared Eastman Gang, killed would-be assassin Julie Morell in the club. Allegedly fellow Eastman Gang members Jack Siroco and Chick Tricker had sent Morrell to off Zelig so they could wrest control of the operation from him. While Zelig turned the tables and survived that night, he would eventually meet his undoing nearby just a year later when he was shot in the head on a Second Avenue streetcar heading north from Segal’s Cafe at 76 Second Avenue, en route to 14th Street.

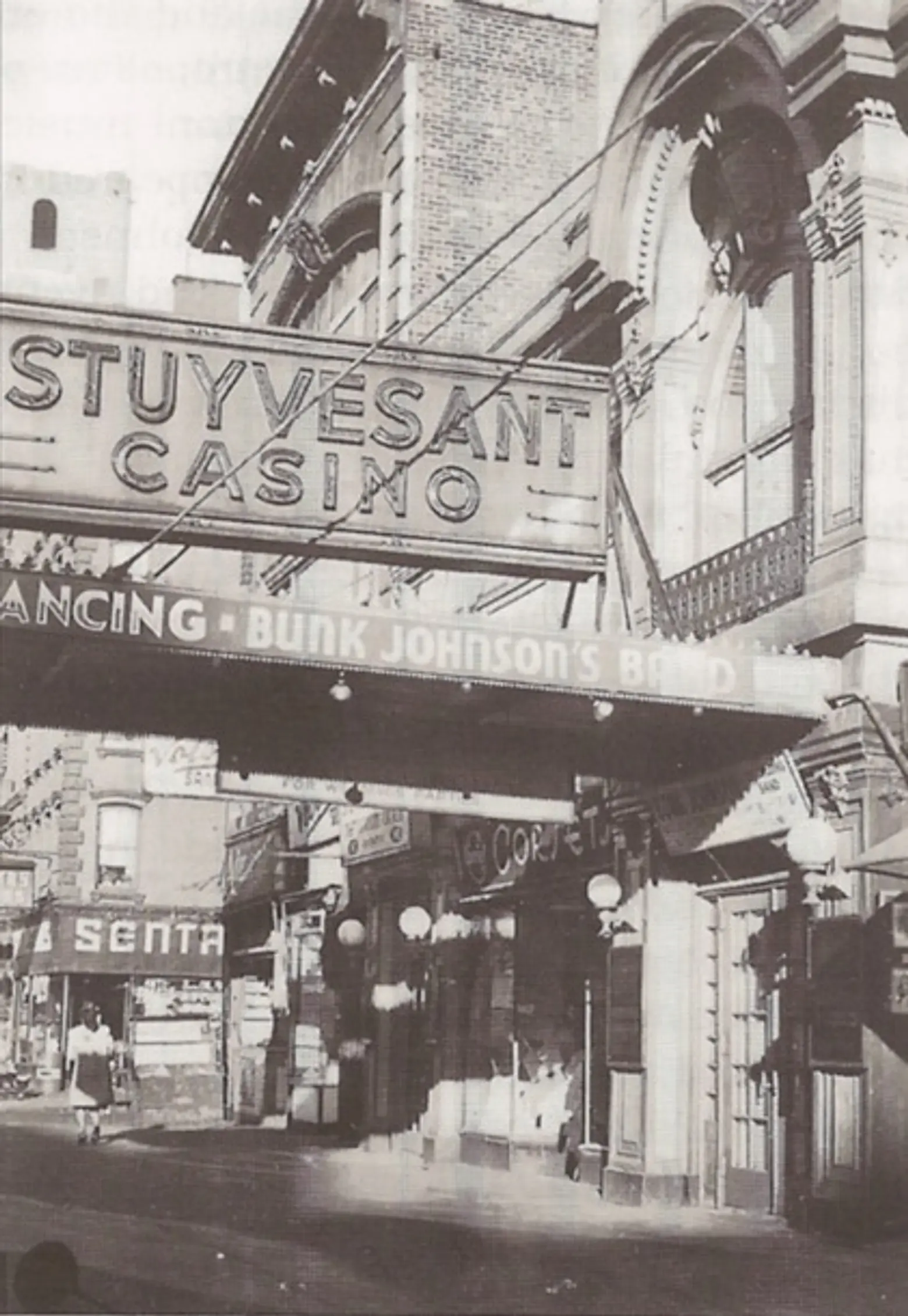

The Stuyvesant Casino in 1945 (top) and Bunk’s New Orleans Band playing there (bottom), via the Swedish Buck Johnson Society

The Stuyvesant Casino in 1945 (top) and Bunk’s New Orleans Band playing there (bottom), via the Swedish Buck Johnson Society

By World War II the Stuyvesant Casino became noteworthy for a different kind of hit. The venue became a popular and celebrated center of jazz performance, particularly known for showcasing New Orleans and Dixieland jazz. New Orleans bandleader Bunk Johnson frequently performed there, sometimes with Louisiana-born bluesman Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter, who lived a few blocks away on East 10th Street. Saxophone great Steve Lacy, who began hanging out at the Casino as a teenager and was exposed to Dixieland Jazz greats there, some of whom he would later play with at the venue, was also a regular. So was revered trumpeter Hot Lips Page, who recorded a version of the 1924 classic “When My Sugar Walks Down the Street” at the Casino, and who opened rival venue Birdland with Charlie Parker (who lived nearby in the East Village on Avenue B), in 1949.

Within a few years, however, the neighborhood was changing again, and 140-142 Second Avenue changed along with it. Darker days settled over the East Village, as drugs, crime, and abandonment plagued the area. Immigration, once the neighborhood’s lifeblood, had been cut to a trickle by restrictive immigration laws, with refugees from Eastern European communism such as Poles and Ukrainians, and Puerto Ricans who had U.S. citizenship, among the few newcomers to arrive as others fled. The Stuyvesant Casino shut down, and the building was eventually taken over by the Ukrainian National Home.

Of course, the East Village soon became known for channeling that darkness and despair that into new and creative forms, and even the Ukrainian National Home got in on the act. In the early 1970s, punk was born in this neighborhood at nearby grungy Bowery bar CBGBs. That stripped down musical movement then migrated to England, where it exploded in popularity, splintering into multiple strains.

Of course, the East Village soon became known for channeling that darkness and despair that into new and creative forms, and even the Ukrainian National Home got in on the act. In the early 1970s, punk was born in this neighborhood at nearby grungy Bowery bar CBGBs. That stripped down musical movement then migrated to England, where it exploded in popularity, splintering into multiple strains.

None of those strains was darker than the gloomy, ethereal punk of Joy Division, who hailed from Manchester, a hollowed-out post-industrial city in the north of England whose decay and deterioration in many ways mirrored the East Village of the late 1970s. In 1980, Joy Division’s lead singer Ian Curtis killed himself, just as the band was about to for the first time tour America, the land where their musical genre was born.

The band slowly reorganized itself, moving guitarist Bernard Sumner into the lead singer position, adding keyboardist Gillian Gilbert, and renaming themselves New Order. They struggled, however, to forge their own sound and identity, seeking to maintain their punk roots while also incorporating new influences and establishing a new and distinctive voice.

Video of New Order playing “Temptation” at the Ukrainian National Home, via VanishInFright/YouTube

A critical moment in that journey came on November 18, 1981, when they finally arrived in America for their very first tour. Though Joy Division had gained prominence and notoriety in Europe, New Order, still to even release a full album, had a much more modest following in America. As a result, their first New York gig was at the Ukrainian National Home, a space that attracted a small but dedicated group of fans and curious onlookers.

The performance that night and the next were turning points for the band. They tested out new material which built upon Joy Division’s spare, stripped-down sound, adding more layers and rhythms for a bigger, more propulsive and enveloping sound. Here they performed for one of the very first times an early, 10-minute version of their epic single “Temptation,” which had not yet been recorded or released, and was still going by the name “Taboo No. 7.”

The song and the performance garnered rave reviews and helped solidify New Order’s reputation as a leader of the post-punk genre. New Order would go on to revolutionize popular music in the 1980s and 1990s, merging synthesizer-driven dance music with the spare edge of punk, making the former dark and cool, and the latter more expansive and multi-layered.

By all accounts, New Order was deeply influenced in this endeavor by the sounds they encountered in New York on these early trips. The spartan “No-Wave” music and synth-based Freestyle and Electro they heard at downtown clubs were the product of white, Latino, and black artists who were in the early 1980s mixing in the downtown clubs which just a few years earlier spawned the punk rock that inspired the first phase of the band’s career.

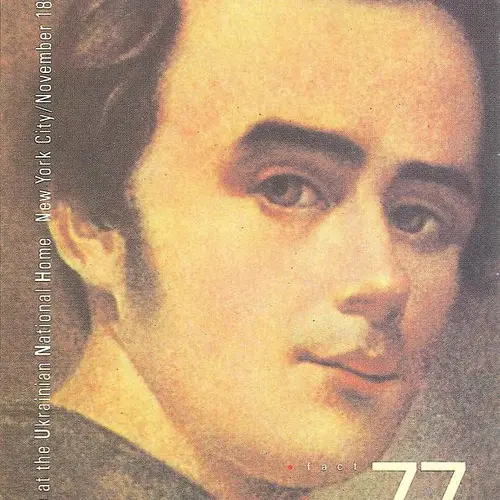

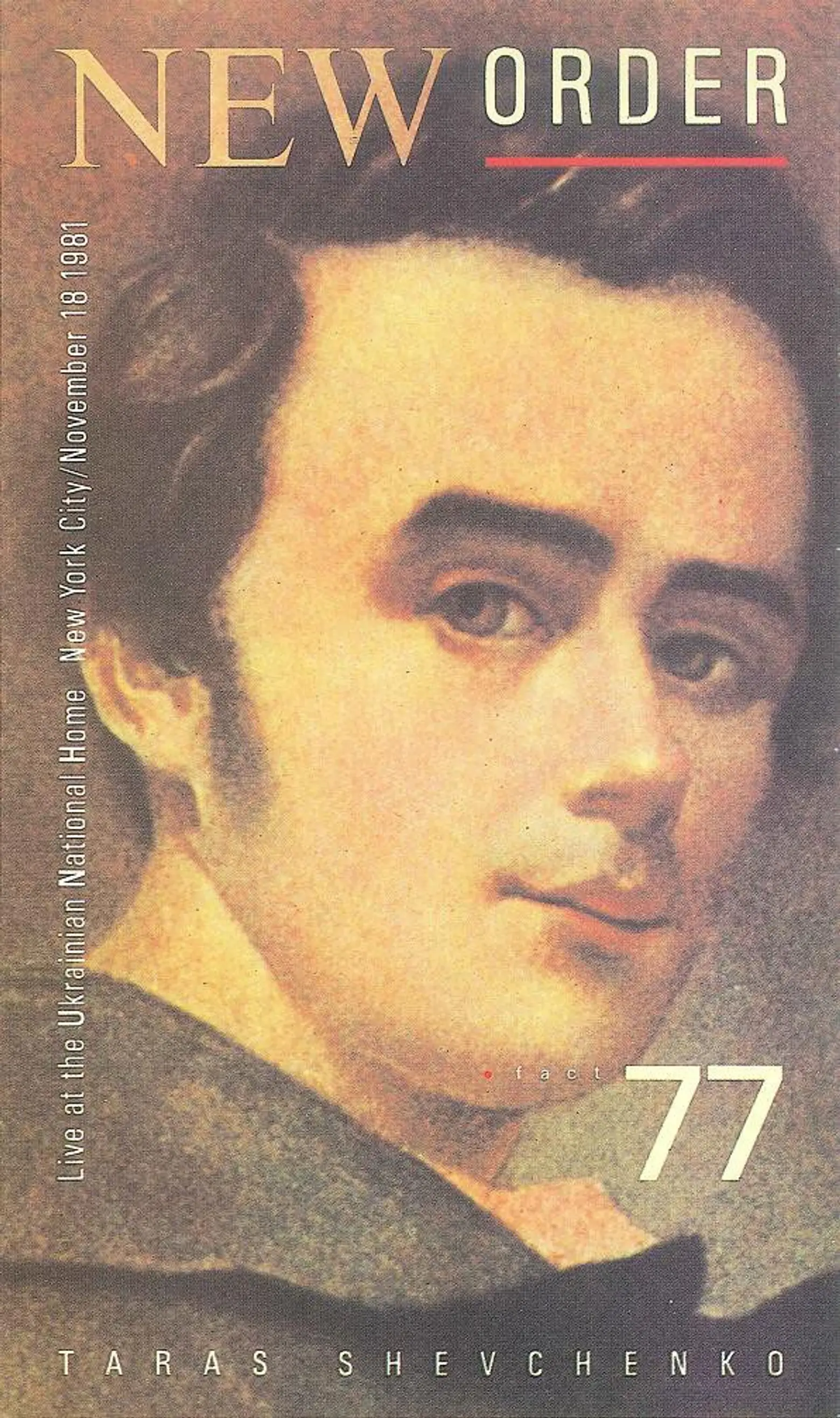

Image via Discogs

Image via Discogs

That seminal 1981 performance was captured on film, and released as “Taras Shevchenko” on VHS in 1983 and DVD in 2001. Taras Shevchenko was a 19th-century Ukrainian nationalist writer, artist, political figure, and folklorist considered to be the father of the modern Ukrainian literature and nationalism; a small one-block street near the Ukrainian National Home between 6th and 7th Street had been renamed in his honor in 1978.

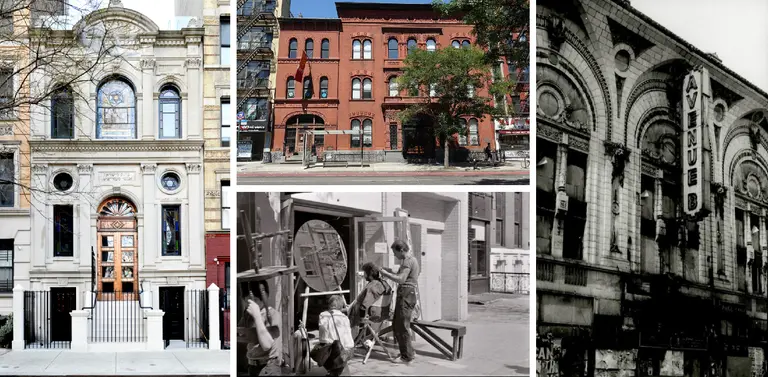

Aside from capturing this seminal performance, the video also captures an image of the Ukrainian National Home as it appeared at the time, with the grand early 20th-century façade covering what had been two early 19th century houses underneath still intact. Sadly, just a short while later in 1984, a fire engulfed the home, destroying the roof and much of the façade. It was after this devastating conflagration that the home’s present metallic covering emerged, designed by local Ukrainian architect Augustyn Sumyk.

Google Street View of the Ukrainian National Home today

Google Street View of the Ukrainian National Home today

In spite of the building’s somewhat impenetrable looking exterior, few buildings have had such a rich cast of characters pass through during its many lives. How many other buildings can claim a lineage stretching from Peter Stuyvesant to Ukrainian nationalists, German temperance to Jewish organized crime, and African-American jazz to Manchester electronica?

For more information on the building’s history, read here >>

+++

This post comes from the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Since 1980, GVSHP has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid.