Cracking open the stories of NYC’s most historic bars

With rising rents and ever-changing commercial drags, New Yorkers can take comfort that the city still holds classic bar haunts, some of which have been serving booze for over 100 years. Some watering holes, like the Financial District’s Fraunces Tavern, played a crucial role in major historic events. Others, like Midtown’s 21 Club and the West Village’s White Horse Tavern, hosted the most notable New Yorkers of the time. These institutions all survived Prohibition–managing to serve alcohol in both unique and secretive ways–and figured out ways to serve a diverse, ever-changing clientele of New Yorkers up to this day.

6sqft rounded up the seven most impressive bars when it comes to New York City history–and they’ve got the legends, stories, and ghosts to prove it. From longshoreman bars to underground speakeasies to Upper East Side institutions, these are the watering holes that have truly withstood New York’s test of time.

Fraunces Tavern by Karl Loeffler via Flickr/Creative Commons

Fraunces Tavern by Karl Loeffler via Flickr/Creative Commons

1. Fraunces Tavern

54 Pearl Street, Financial District

This bar is so old–the oldest in New York, in fact–that it comes with a museum. Samuel Fraunces, who immigrated to Manhattan from the Caribbean, opened the bar in 1762 as the Queen’s Head Tavern. It immediately became a popular watering hole, one that would play a major role as a de-facto headquarters during and after the American Revolution. As elaborate “turtle feast” dinner was served to George Washington after the British troops evacuated New York. The tavern was also a venue for peace negotiations with the British, and housed federal offices in the Early Republic.

Fraunces Tavern between the 1890 alteration and the 1900 restoration, via the Fraunces Tavern Museum

Fraunces Tavern between the 1890 alteration and the 1900 restoration, via the Fraunces Tavern Museum

Numerous fires changed the building throughout the years, and in 1900, the tavern was slated for demolition by its owners to build a parking lot. After outcry from the Daughters of the American Revolution, the Sons of the Revolution in the State of New York Inc. purchased the building in 1904 and carried out a major reconstruction, claiming it as Manhattan’s oldest surviving building. The building was declared a landmark in 1965.

You can still grab a drink and a meal at the tavern once frequented by George Washington. And since 1907, the second and third floors of the building have held the Fraunces Tavern Museum, a collection of paintings and artifacts preserved during the building’s long history.

The Ear Inn by Susan Sermoneta, via Flickr/Creative Commons

The Ear Inn by Susan Sermoneta, via Flickr/Creative Commons

2. Ear Inn

326 Spring Street, Soho

Ear Inn also ranks as one of the oldest operating drinking establishments in the city. The building was constructed around 1770 for James Brown, an African aide to George Washington during the Revolutionary War. (Brown is said to be depicted in the famous Emmanuel Leutze painting of Washington’s Delaware River crossing.) Due to its location just a few blocks from the Hudson River, the bar became a popular spot with sailors and dock workers as the waterfront exploded with new piers built to facilitate constant shipping traffic.

After Brown passed away, Thomas Cooke took over the building and began selling sold home-brewed beer and crocks of corn whiskey to the constant wave of sailors in the mid 1800s. Then, by the early 1900s, the spot was selling food with a dining room constructed where the backyard and outhouse once stood. During Prohibition, the bar became a speakeasy. After prohibition, it reopened to the public with no name–just with a reputation as “a lady-free clubhouse for sailors to eat, drink, gamble,” according to the Ear Inn website. The upstairs of the townhouse has served as everything from a boarding house to smuggler’s den to brothel to doctor’s office.

Historic photo of the Ear Inn, via MAS

Historic photo of the Ear Inn, via MAS

The bar got its unique name in the 1970s. Current owners Martin Sheridan and Richard “Rip” Hayman decided to call it The Ear Inn to avoid the Landmark Preservation Commission’s review process of new signage. They simply covered the round parts of the long-standing neon “BAR” sign, leaving it to read “EAR.” With the exception of the name change, the two-and-a-half story Federal style townhouse remains virtually untouched since its 1770 beginnings. And though it’s no longer mobbed by sailors, Ear Inn picked up some ghosts along the way, including Mickey, who’s been patiently waiting for his clipper ship to come into the harbor for the past 100 years.

McSorley’s by (vincent desjardins) via Flickr/Creative Commons

McSorley’s by (vincent desjardins) via Flickr/Creative Commons

3. McSorley’s Old Ale House

15 East 7th Street, East Village

McSorley’s is perhaps New York’s most well-known historic bar. It opened in 1824, by the Irish immigrant John McSorley. Way back then, it was considered an Irish working man’s saloon, with cheese and crackers on the house and beer selling for pennies. Between 1864 and 1865, the building was improved to become a five-story tenement, so John and his family moved upstairs over the bar. The McSorley family purchased the entire building in 1888.

The early 1900s brought a “brief experimental period” in which McSorley’s served hard liquor along with the ale. It didn’t last long, and McSorley’s remained an ale house from that point forward. (Through Prohibition, they get away with selling what the bar called “Near Beer.”) After John McSorley died in the second floor flat above the bar, at the age of 83, his son Bill took over and used the bar to make a shrine for his departed father. This unique, boozy shrine, however, wasn’t open to all New Yorkers–after prohibition, when many of New York bars started admitting women, McSorley’s continued to hold its philosophy of “Good Ale, Raw Onions, and No Ladies.”

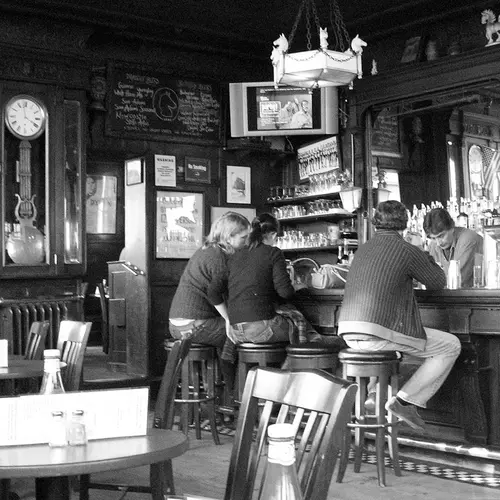

Inside McSorley’s, by Antonio Rubio via Flickr/Creative Commons

Inside McSorley’s, by Antonio Rubio via Flickr/Creative Commons

The bar sold to New York City policeman Daniel O’Connell in the 1930s, and he and his daughter did little to change the atmosphere. After New Yorker writer Joseph Mitchell published his book, “McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon” in the 1940s, it got attention from around the country. Still, women weren’t allowed inside–and wouldn’t be until 1970, after the bar owners got sued for discrimination. A woman’s restroom was finally installed in 1986, and the first woman to work behind the bar started serving ales in 1994. Now everybody wonders at an interior still caked with old photos, yellowing newspaper articles, and historic knick-knacks. At the bar, you can only order the one beverage McSorley’s has served in its long history–though you do have the option to get your ale either dark or light.

Old Town Bar, by Jazz Guy via Flickr/Creative Commons

Old Town Bar, by Jazz Guy via Flickr/Creative Commons

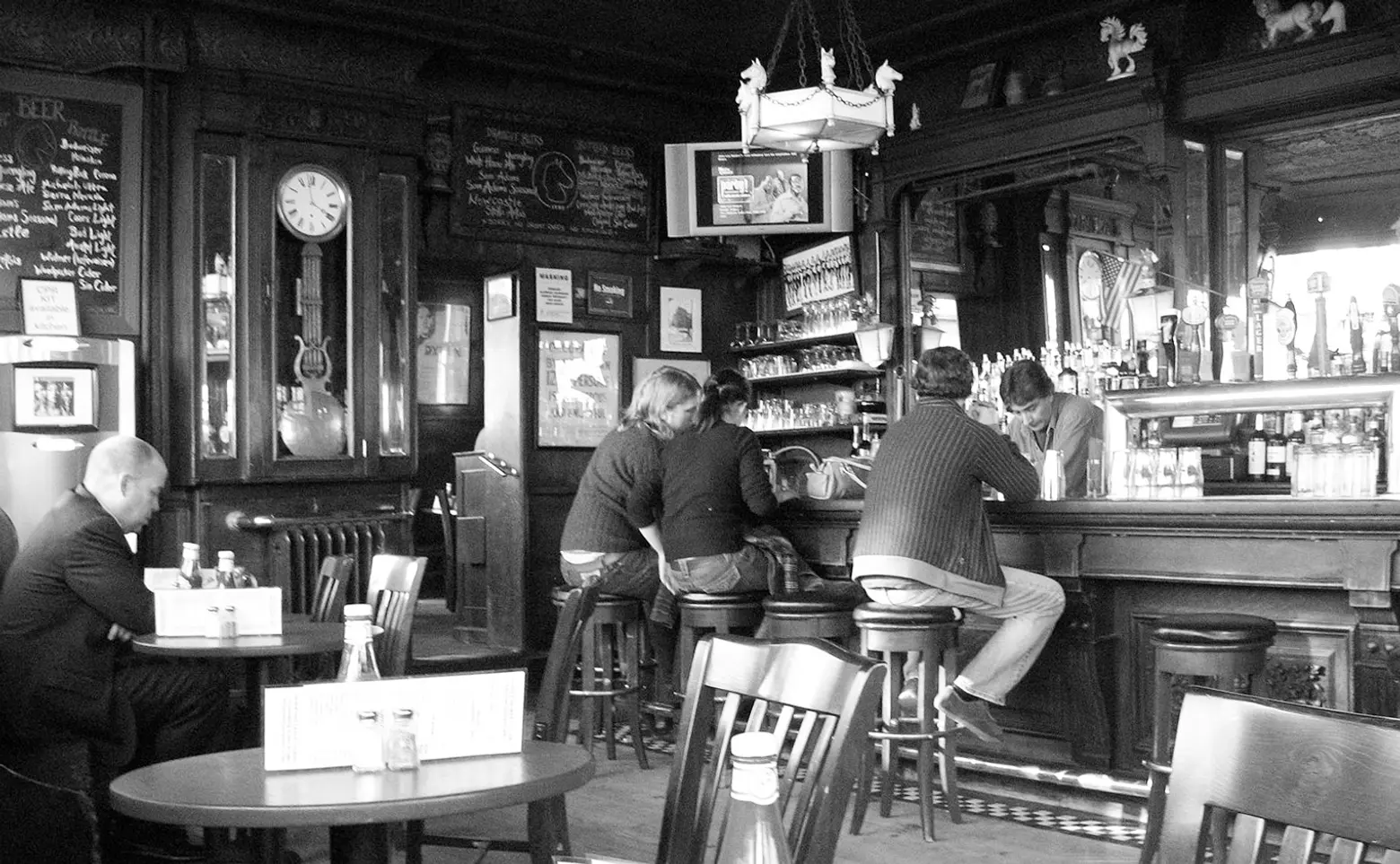

4. Old Town Bar

45 East 18th Street, Flatiron District

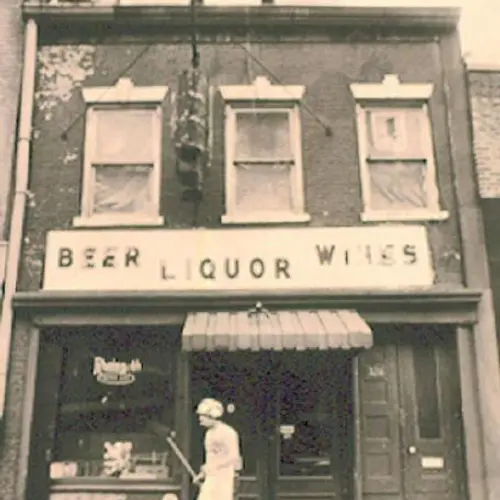

Old Town Bar was originally a German establishment called Viemeisters, which opened in 1892. The spot only served drinks, but during Prohibition, it was forced to change its name to Craig’s Restaurant and start serving food–while also operating as a speakeasy. Throughout the ’20s, it was known as a roaring speakeasy. But by the end of Prohibition, followed by the closing of the nearby 18th Street Subway station in 1948, the bar fell into disrepair. It wasn’t until the late 1960s, when bar manager Larry Meagher took over operations, that it got a second life.

Historic photo of Old Town Bar, via the Old Town Bar website

Historic photo of Old Town Bar, via the Old Town Bar website

Meagher restored the 19th-century, 55-foot wooden bar that has always distinguished the space. The bar maintains tons of historic details: high tin ceilings, large original mirrors, antique cash registers, giant urinals made in 1910, and dumbwaiters. The impressive interior has made this a popular place for shooting movies and television, from Sex and the City to The Last Days of Disco.

Old Town Bar interior, by Jazz Guy via Flickr/Creative Commons

Old Town Bar interior, by Jazz Guy via Flickr/Creative Commons

Old Town still serves booze and food to a diverse mix of patrons. The author Frank McCourt once called Old Town “a place to talk,” something that stays true into present day.

White Horse Tavern by Katie Killary via Flickr/Creative Commons

White Horse Tavern by Katie Killary via Flickr/Creative Commons

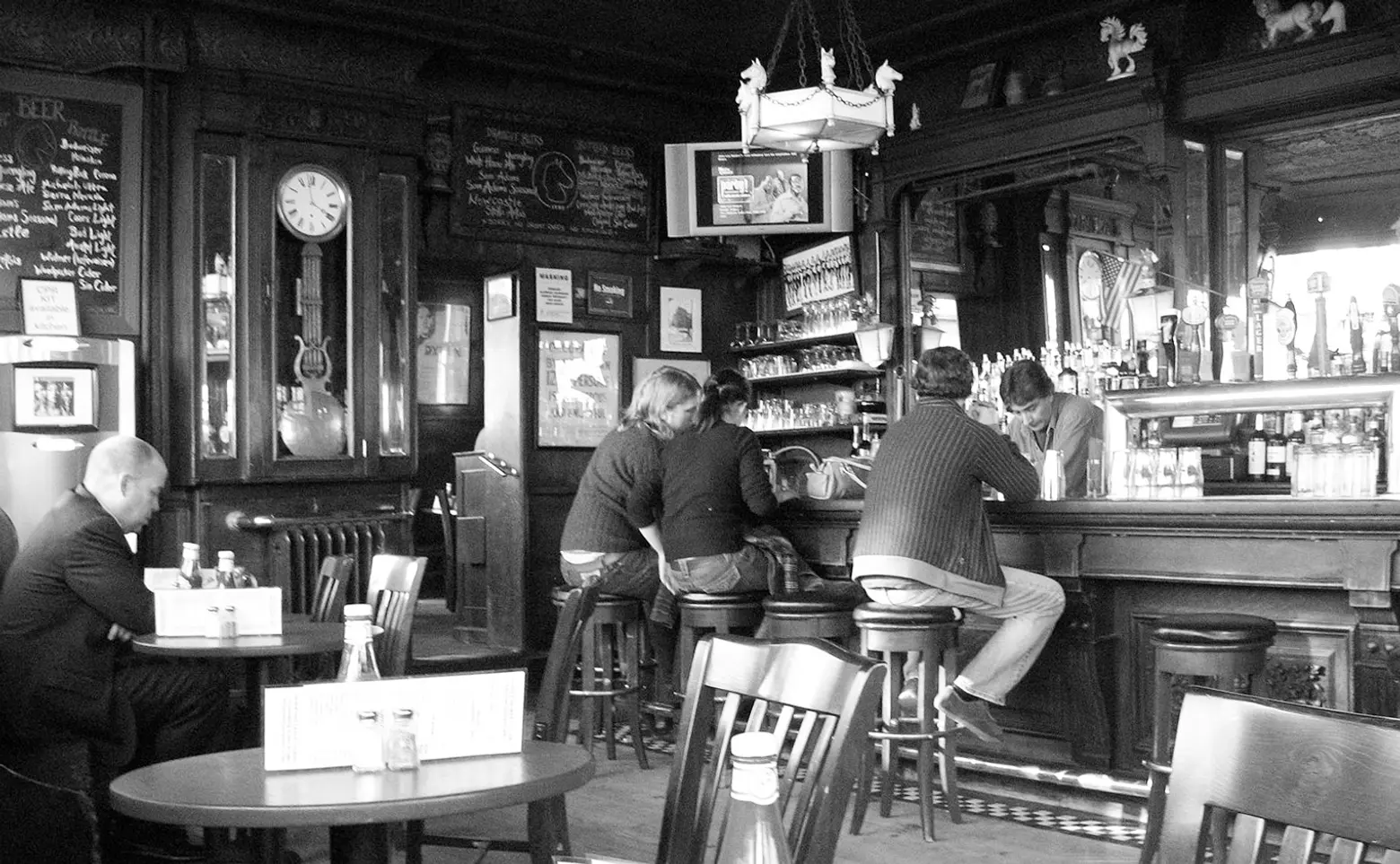

5. White Horse Tavern

567 Hudson Street, West Village

This West Village haunt opened in 1880 and quickly earned a reputation as an after-hours longshoreman’s bar serving the men working the Hudson River piers. But the White Horse–nicknamed “The Horse”–picked up a new clientele in the 1950s, when the bar became popular with writers and artists. The poet Dylan Thomas found the tavern reminiscent of his favorite haunts in his home country of Wales. But after he downed an alleged eighteen shots of whiskey here in 1953, legend has it that he immediately stumbled outside, collapsed on the sidewalk, and later died at St. Vincent Hospital.

White Horse Tavern interior via Wiki Commons

White Horse Tavern interior via Wiki Commons

Portraits of Thomas embellish the walls, and a plaque commemorating his last trip to the tavern hangs above the bar. Other literary giants to frequent the pub include James Baldwin, Anais Nin, Norman Mailer, John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and Bob Dylan. To this day, the interior features white horse pictures and figurines alongside heavy wood paneling that hasn’t changed much throughout its history.

The 21 Club by Wally Gobetz, via Flickr/Creative Commons

The 21 Club by Wally Gobetz, via Flickr/Creative Commons

6. 21 Club

21 West 52nd Street, Midtown

The 21 Club emerged out of Prohibition, moving several times before landing in Midtown. Cousins Jack Kreindler and Charlie Berns opened the club in 1922 in Greenwich Village as a speakeasy, then moved it to a basement on Washington Place, then moved it uptown, and finally to its current location in 1930 to make way for the construction of Rockefeller Center. (Although raided by police numerous times during Prohibition, the two cousins were never caught.)

The club became more exclusive each time it moved, and the Midtown location got a reputation for its vast array of liquor–accessed through a secret, underground wine cellar–and impressive menu. The reputation held; the bar and restaurant went on to host Presidents John F. Kennedy, Richard Nixon, and Gerald Ford, Joan Crawford, Elizabeth Taylor, Ernest Hemingway, Marilyn Monroe and a number of other celebrities.

21 Club interior, via 21 Club

21 Club interior, via 21 Club

The bar is known for its eclectic art collection, from the jockeys decorating the front facade to toys hanging from the ceiling. Sportsman and 21 regular Jay van Urk donated the first jockey to the bar in the early 1930s, and more jockey figurines followed from families like the Vanderbilts, Mellons and Ogden Mills Phipps. The legendary toy ceiling collection also started in the 1930s, when the owner of British Airlines asked Jack and Charlie if he could hang a model of his plane over the table to impress some investors. The cousins agreed, and soon competitors and captains of industry insisted on adding their mementos, too.

Bemelman’s Bar, via the Carlyle Hotel

Bemelman’s Bar, via the Carlyle Hotel

7. Bemelman’s Bar

35 East 76th Street, Upper East Side

For a classic, old New York cocktail, look no further than Bemelman’s, the snug bar situated inside the Carlyle Hotel. The Carlyle is an opulent Upper East Side hotel that gives off an air of “old money,” and Bemelman’s falls right in line. When the cocktail bar was under construction in the 1930s, the hotel owners came to an unusual agreement with one of its guests regarding its interior design. Ludwig Bemelmans, creator of the children’s series Madeline and namesake of the bar, was asked to paint murals on the walls depicting scenes of Central Park. In exchange, he and his family got to stay at the Carlyle Hotel for a year-and-a-half for free.

Bemelman’s Bar, via the Carlyle Hotel

Bemelman’s Bar, via the Carlyle Hotel

There are other lavish interior touches, like the nickel-trimmed glass tables, brown leather banquettes, a grand piano and a ceiling is coated with 24-karat gold leaf. The live music and decadent Art Deco ambience is quite enough to justify spending a pretty penny on a cocktail.

RELATED: