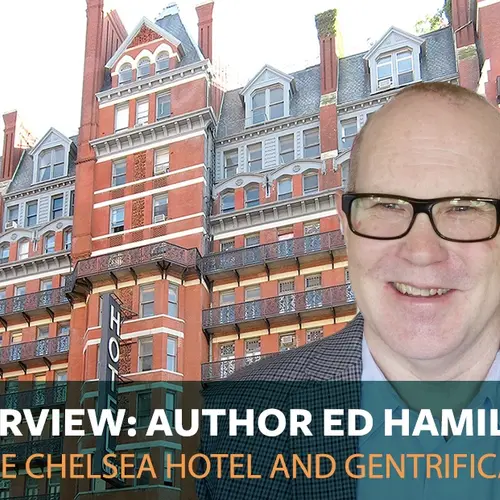

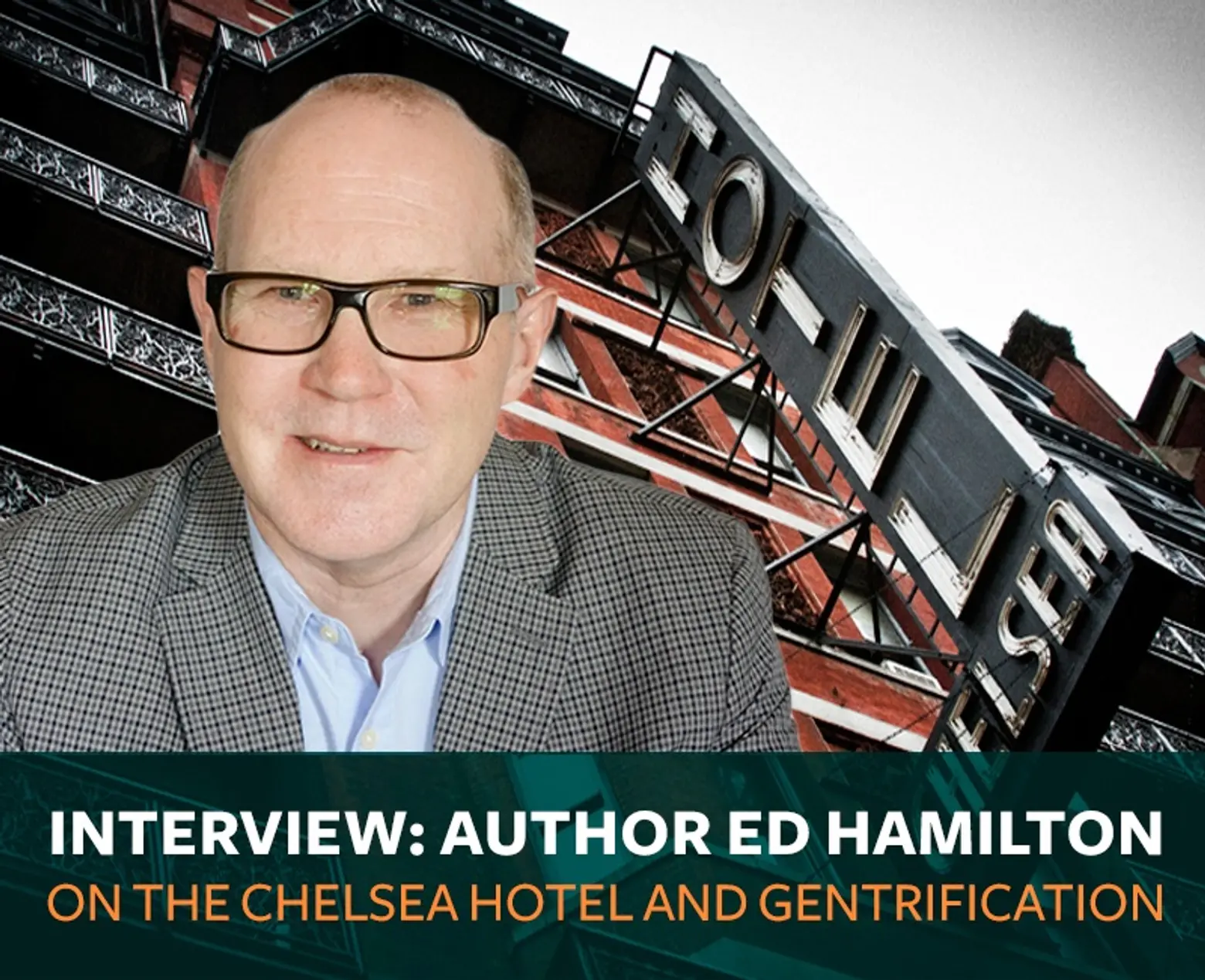

INTERVIEW: Author Ed Hamilton on how the Chelsea Hotel inspired personal stories of gentrification

Background image via Andrew Malone/Flickr

When it comes to the Chelsea Hotel, Ed Hamilton has seen it all. He and his wife moved to the iconic property in 1995, living among artists and musicians in a 220-square-foot, single-room-occupancy unit. The storied, artistic community nurtured inside the hotel came to an end a decade ago when the building sold for the first time and evictions followed. Since then, the property has traded hands a number of times with talks of boutique hotel development, luxury condos, or some combination of the two. Hamilton started tracking the saga at his blog Living With Legends and published a book, “Legends of the Chelsea Hotel,” in 2007.

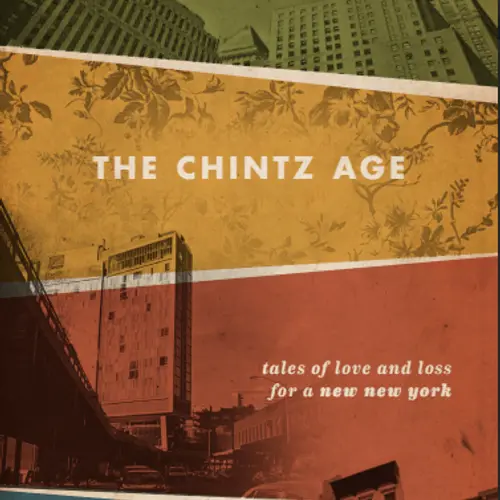

After the book’s success, Hamilton wrote a short story collection titled “The Chintz Age: Stories of Love and Loss for a new New York.” Each piece offers a different take on New York’s “hyper gentrification,” as he calls it: a mother unable to afford her lofty East Village apartment, giving it up to a daughter she shares a strained relationship with; a book store owner who confronts his failed writing career as a landlord forces him out of now highly valuable commercial space.

Ultimately, many of the stories were inspired by the characters he met inside the Chelsea Hotel. And his tales offer a new perspective on a changing city, one that focuses on “the personal, day-to-day struggles about the people who are trying to hang onto their place in New York.” With 6sqft, he shares what it’s like writing in the under-construction Chelsea Hotel, what the Chintz Age title means, and the unchanged spots of the city he still treasures.

Where did you find the inspiration for this book?

Ed: The inspiration did come from the Chelsea Hotel. My first book came out right when the hotel was being taken over by developers. I saw the place get torn up and 50 of my artist friends get evicted. The whole thing was just heartbreaking.

I got lots of attention for my [previous] book, but it was mixed with a deep sadness since the attention came partly from the hotel being taken over and destroyed. I struggled for a long time, thought about writing a sequel, and wrote about 100 pages of it. I couldn’t get into it as much; the magic and joy had gone out of it. So I moved away from that intense fixation on the hotel to explore the rest of the city.

The Chintz Age is based on people I’ve known in the Chelsea and around the city, but it’s about other neighborhoods of New York. I fictionalized the stories, too, to get more inside the heads of the people I’m discussing.

As for the theme, it’s about the personal, day-to-day struggles of the people who are trying to hang onto their place in New York. That’s what I saw going through this trauma with the Chelsea Hotel. There are all these large forces, like gentrification and development, but that doesn’t get into the human dimension of gentrification. There’s a very human level to this greed-centered development that’s turning our city more and more into a playground for the rich.

By writing fiction, you were really able to tell these personal stories about families, or small business owners, in the context of larger changes happening in the city. What attracted you to these types of personal stories?

Ed: Some of the characters are based on people I’ve known in the past. But what I really wanted to examine was how do you hold onto the past and your ideals as an artist while moving forward into the future? It’s something I struggle with myself. I’ve lived in this building around creative people all my life, and we’ve all gone through this struggle. We considered the Chelsea Hotel an insular environment that was protected by outside forces. This takeover threw us into the real world. We all want to hold onto the past, the bohemian ideals of New York, but it can be self-defeating. You still have to move forward and carve a place out for yourself. That’s what I wanted to explore in these stories. I tried to see it from different points of view: through a mother and daughter relationship, and from someone who’s benefiting from gentrification.

Photo via Pexels

What do you make of the current transformation of the city, with more money and development pouring in? What do you see is happening to the city now?

Ed: Calling it gentrification—well, I think we need a new word for it. Gentrification is not all that bad if it’s gradual and if people who move to a neighborhood want to be a part of it. We’re seeing a weird hyper-gentrification, moving at warp speed and totally transforming the city in a way that’s not organic or people driven. It’s all development driven.

One major problem is surrounding the Limited Liability Companies or LLCs. Many buildings, including the Chelsea Hotel, are owned by a string of LLCs and it’s a way to hide money and speculate on real estate. We don’t really even know who the owner of the Chelsea Hotel is. It’s weird that you have to give your name to apply for a credit card, but you don’t have to give your name if you’re gonna own a $100 million building.

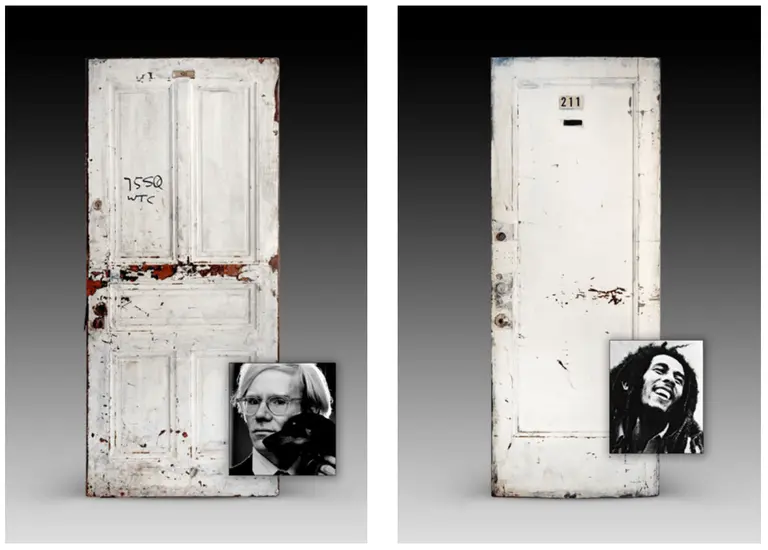

Photo via Wiki Commons

Photo via Wiki Commons

So what’s been happening recently at the Chelsea Hotel?

Ed: We don’t really know what is going on here at the Chelsea Hotel. 10 years ago the minority shareholders took over the hotel from the majority owner and for about four years they tried to sell it. It eventually did sell and it’s changed hands a few times. They’ve been doing so-called renovations for six years now. It’s a nightmare, filled with dust and noise. There’s scaffolding blocking both my windows. They evicted 60 or 70 apartments full of people, and there are still 50 apartments left. Our speculation is they’re trying to get rid of more people before opening the place up.

It must be an emotional experience writing inside the hotel as it happens.

Ed: It’s hard to even express. I still manage to do my writing and draw inspiration from the place, but I’m frustrated about the whole thing. It’s been heartbreaking to see people get tossed out, some who didn’t have the money and others through legal maneuverings. It feels like a sword, hanging over your head. When’s the sword gonna fall on me? But what [the developer’s] got left are a lot of people who love the hotel and are dedicated to staying.

What was your favorite story to write in The Chintz Age?

Ed: My favorite to write was the last story, “The Retro ’70s Manhattan Dream Apartment.” It has a happiness and joy of celebrating the old-time Bowery and an old-time apartment left over from the ’70s. It’s a wacky tour into the past.

I really like “West Side Hotel;” it’s like the Chelsea Hotel got transported to the West Side, in Hell’s Kitchen. I had fun with that because I produced a noir atmosphere, capturing the darkness and isolation of that area. But, also, the gentrification coming there as well with clubs and galleries opening.

How did you come up with the title?

Ed: I wanted to express the notion that whenever you get something replaced—even your faucets—the old things are inevitably better than the new ones. That’s what we found around the Chelsea; they’ve come and replaced everything that had lasted 125 years with plastic garbage that’s falling apart after five years. It feels like everything has planned obsolescence these days.

It applies to the city itself. The older buildings, in most cases, are objectively more beautiful than these glass-and-steel boxes. And I know what’s inside—because we’re getting it at the hotel—it’s cheap plastic fixtures. We have a lot of people coming into the city, but instead of praising the old or augmenting it with better stuff, it’s getting torn down and being replaced with strip malls.

Eisenberg’s via Google Maps

Eisenberg’s via Google Maps

So what are your favorite places in New York that retain the character of the city you love?

Ed: I don’t know if I want to tell you! No, there are still a lot of pockets. A couple diners, like Eisenberg’s Diner on 5th Avenue and B&H on the Lower East Side. I like St. Marks in the Field, a nice place to sit that isn’t overrun with people. And long walks in places off the beaten path—the only place left now, I think, is walking up 10th Avenue. You can walk up 10th to Riverside Park, which hasn’t been destroyed. They fixed it up and I’d say it’s one example of change for the better.

RELATED: