A tribute to Frank Lloyd Wright’s built, unbuilt, and demolished New York works

For many, Frank Lloyd Wright is considered the archetype of his profession; he was brash and unapologetic about his ideas, he experimented and tested the limits of materiality and construction, and he was never afraid to put clients in their place when they were wrong. It was this unwavering confidence paired with a brilliant creative mind that made him one of the greatest American architects to ever live. And one of the most influential.

This week Wright would have turned 150 years old, so to celebrate his birthday and his importance to the practice of modern architecture, we’re paying tribute to the architect’s built, destroyed, and never-constructed New York works. Amazingly, of the more than 500 structures credited with his name, he can only claim one in Manhattan.

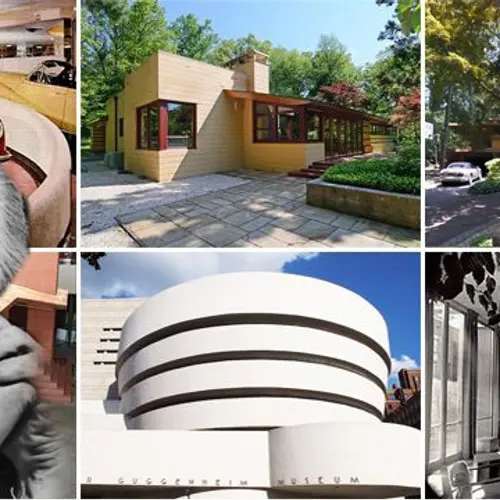

THE GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM

Built nearly 60 years ago, the Guggenheim continues to awe visitors even today. Wright was commissioned by Solomon R. Guggenheim alongside his artist friend Hilla von Rebay (who introduced Guggenheim to modern art and was the reason he began collecting avant-garde works) in 1943 to build a space to house his vast collection. Wright accepted the commission, seeing it as an opportunity to bring his organic style into the heart of a city (the architect hated urban density). Rebay wanted the museum to be a “temple of the spirit” that would provide a new way of experiencing art. And though the design took Wright nearly 15 years to complete (there were six sets of working drawings produced and the museum didn’t open until after his death), Wright was successful in his execution. In addition to a striking exterior, the interior of the museum is like no other. Upon entering, visitors are greeted with a soaring 92-foot atrium space wrapped with a circular ramp. The swirling path also offers a means to explore the interior architecture and the rooms housing the museum’s works.

Notably, while this modern landmark was under construction, Wright took up residence at the famed Plaza Hotel where he lived from 1954 to 1959.

Images via The Steiner Agency

Images via The Steiner Agency

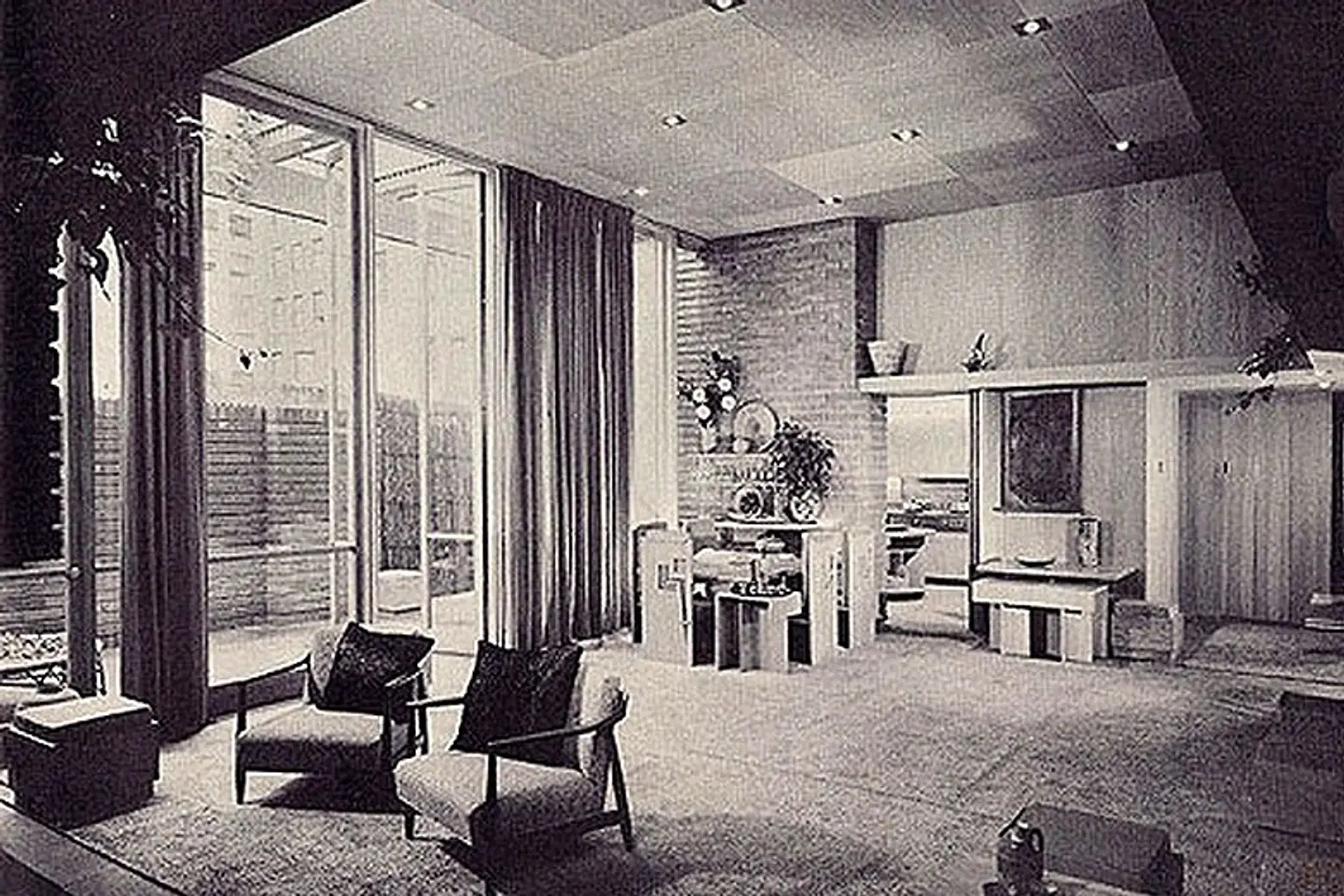

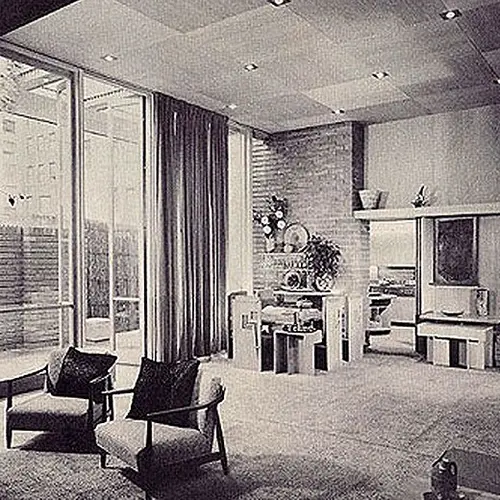

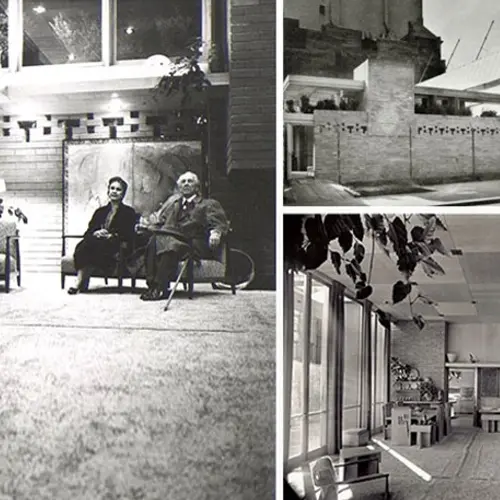

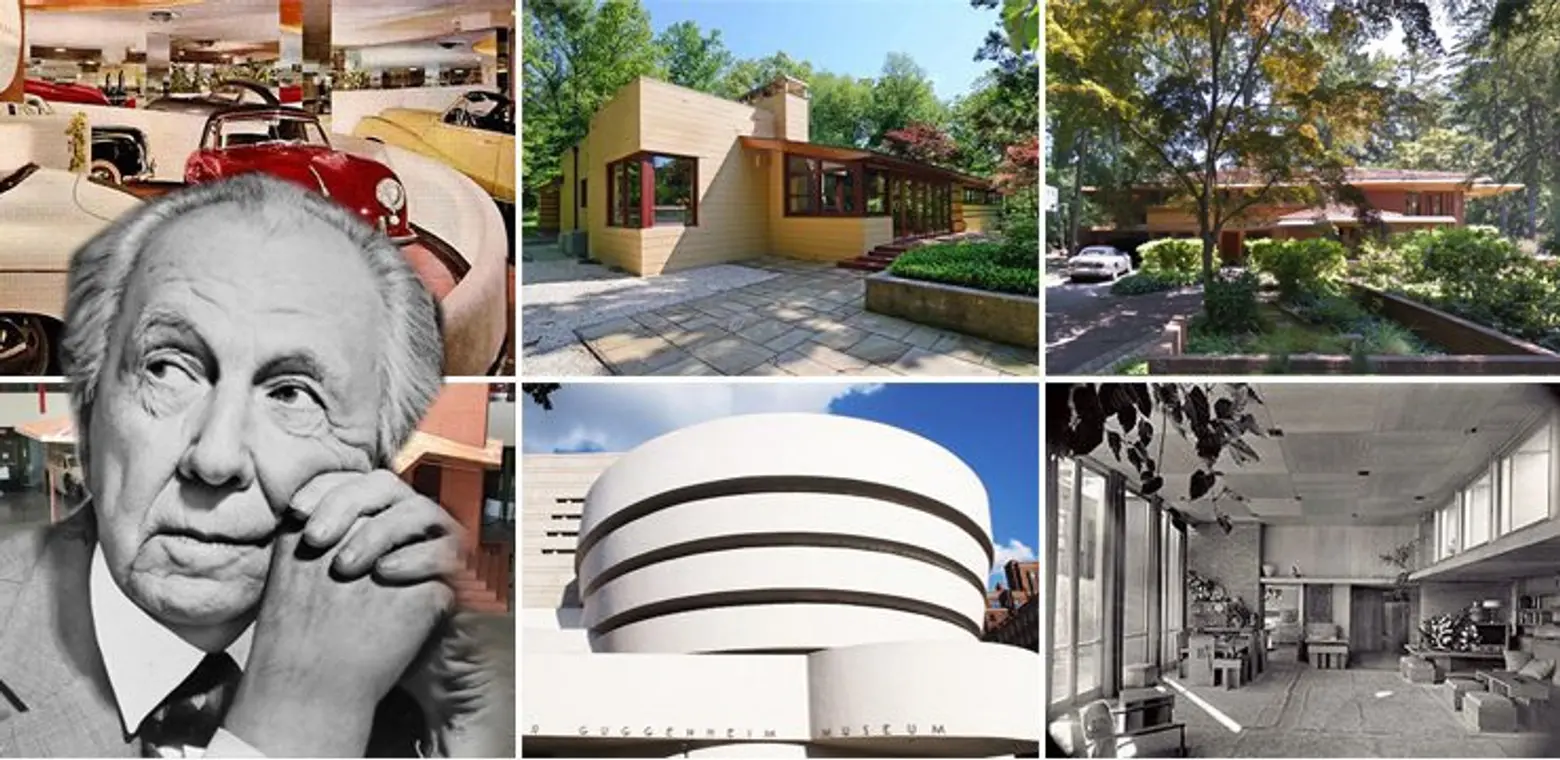

USONIAN EXHIBITION HOUSE AND PAVILION FOR THE GUGGENHEIM (DEMOLISHED)

As part of the Guggenheim commission, Wright held an exhibition in 1953 called “Sixty Years of Living Architecture: The Work of Frank Lloyd Wright” in which he constructed a model Usonian House and pavilion on the site where the museum would eventually rise. Although the home was never meant to stand longer than the stretch allotted for the show, it had quite an impact on New Yorkers. The exhibit introduced many to the work of Wright and his way of thinking. The temporary home had the typical floor-to-ceiling doors and windows, an open plan, and the characteristic cantilevering roof seen in Wright homes in the Midwest. This exhibition provided a wonderful precursor to what would arrive next on site.

[Read more about this project here]

Image © Auto Week

Image © Auto Week

HOFFMAN AUTO SHOWROOMS (DEMOLISHED)

The Hoffman Auto Showroom is another lost treasure, surprisingly meeting its end fairly recently in 2013. The showroom was constructed in 1955 and occupied by Mercedes from 1957 on. The carmaker left the building in January 2012, and just over a year later, the showroom was quietly demolished after the Landmarks Preservation Commission called the building owner to have it declared an interior landmark.

What makes this particular work so unique is not only the fact that it is one of Wright’s few works in Manhattan, but it boasts a familiar central feature: a rotating spiral ramp to display the cars. This facet was most certainly inspired by the architect’s immersion in the design of the Guggenheim which started construction in 1956.

[Read more about this project here]

Images courtesy of Monore Realty

Images courtesy of Monore Realty

THE BLAUVELT HOME

Although Wright’s Prairie style was a sensation primarily taking hold in the Midwest, one of his prefab Prairie creations did make its way upstate. This modest beauty is located in Blauvelt, just a half-hour outside of New York City. In line with the architect’s love for the outdoors, the home sits on a private 2.5-acre property which itself sits within the 500-acre Clausland Mountain Preserve. The home boasts an open floor plan and four spacious bedrooms spread across one floor. Interestingly, this construction was part of a development project Wright worked on with developer Marshall Erdman and is only one of 11 built. The homes were meant to be sold for $15,000 back in the day, but this particular house was last placed on the market for $795,000 in 2014.

[Read more about this project here]

Image via NewYorkitecture.com

Image via NewYorkitecture.com

THE STATEN ISLAND CASS HOUSE

Staten Island isn’t quite the place you’d expect to find a Wright masterpiece, but the Cass House is his only remaining NYC-proper, free-standing structure outside of the Guggenheim. Also known as the Crimson Beech house, this beauty was prefabricated in the Midwest and shipped to Staten Island for its owners William and Catherine Cass. The home was also a part of the aforementioned Marshall Erdman project and was the first design in the series—dubbed “Prefab #1” by Wright scholars. The house features a low L-shape with an open plan layout and a sunken living room and a cathedral ceiling. And though it appears to be just one story, it’s actually two. The second floor at the back of the home follows the slope of the hill on which it is constructed. The original owners lived in the house up until 1999 when it was sold, and today it is still privately owned and occupied by a family.

Image via Google Street View, 9 Myrtle Drive

Image via Google Street View, 9 Myrtle Drive

GREAT NECK LONG ISLAND HOME

Another island home designed by Wright can be found in Great Neck Estates on Long Island. This seven-room structure was erected between 1937 and 1938 for Mr. Rebhuhns, a magazine publisher, and his dress designer wife. The form and height of the home are very much in the vein of the pre-cast concrete Usonian homes Wright constructed on the West Coast more than a decade earlier, but here they are better refined and sited when it comes to materiality. Another cool feature is that it was originally built around an existing oak tree. The ceiling was punctuated to allow the tree to co-exist and grow with the home. Unfortunately, it would eventually die as the result of excessive heat in the house.

Photos courtesy of Chilton & Chadwick

Photos courtesy of Chilton & Chadwick

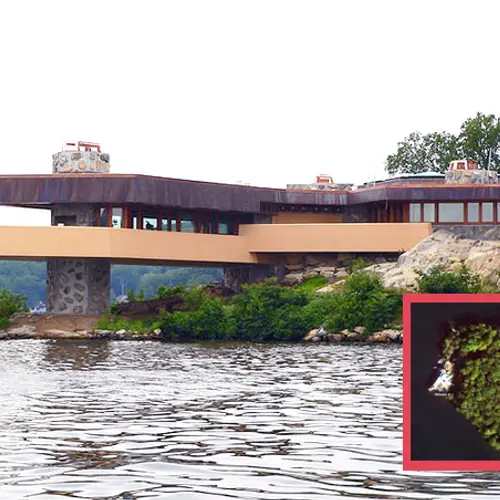

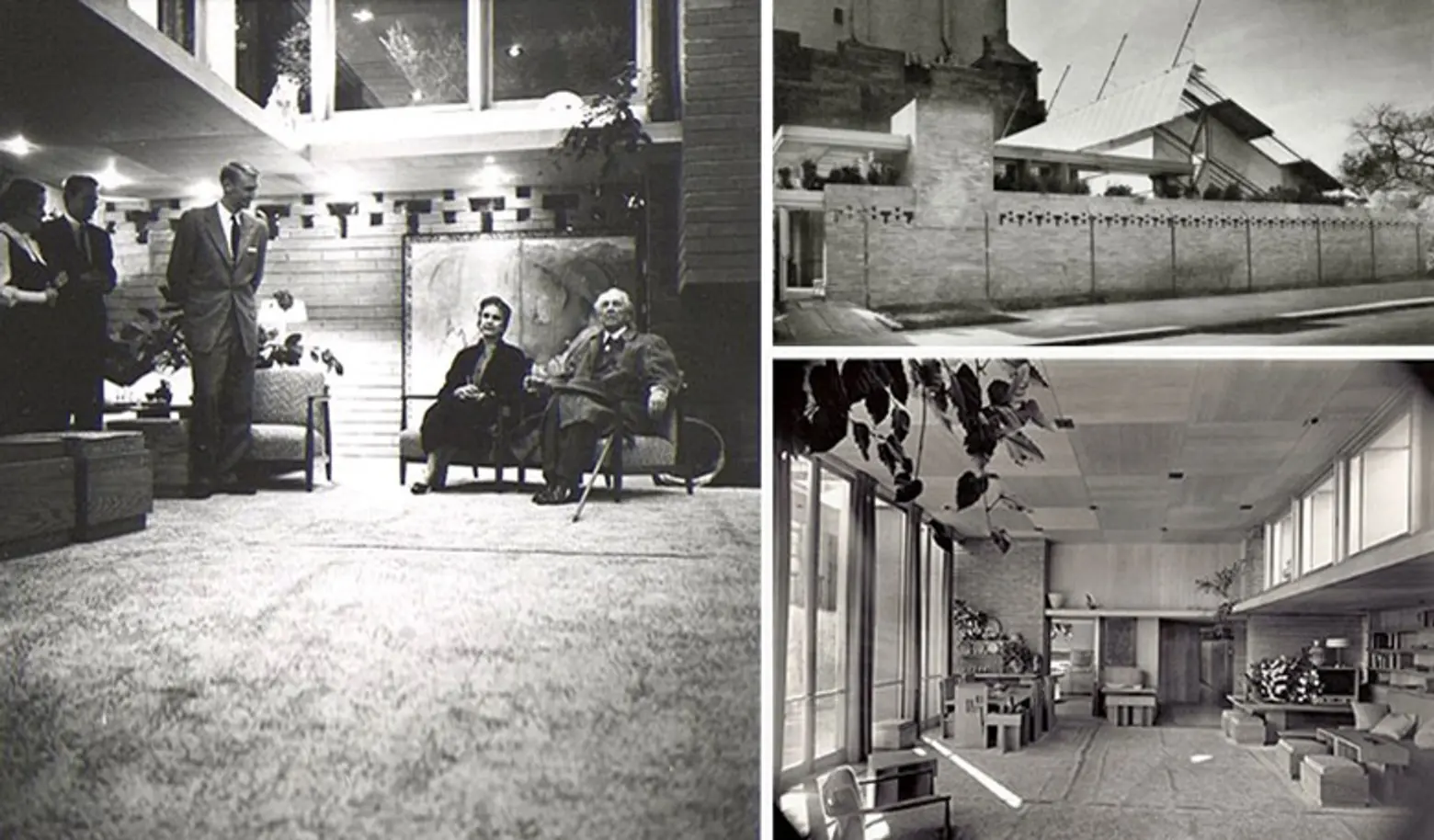

PETRA ISLAND HOME

Located on an 11-acre, heart-shaped island 47 miles off Manhattan, this home is easily one of Wright’s most controversial designs. Wright originally drew up plans for the home back in 1949 but ended up scaling it down due to budgetary concerns. Neither the original nor the downsized versions were ever constructed in the architect’s lifetime, but about 50 years later, the island’s new owner, Joe Massaro, decided to bring the design to fruition. With the help of Wright scholar Thomas Heinz, the pair worked together to create drawings of the first iteration of the home in ArchiCAD. But therein lay the issue: Heinz drafted drawings of parts of the home that weren’t apparent in Wright’s original renderings. He also incorporated a number of modern amenities that would not have otherwise existed. Although the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation refuses to acknowledge the home as a true Wright creation, it hasn’t kept the agents trying to sell the island and home from touting it as such.

Images © The Pierce-Arrow Museum

Images © The Pierce-Arrow Museum

A FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT FUELING STATION

Frank Lloyd Wright was a well-known automobile lover, and to him, the ideal city was one that was open and low-density. As such, it’s only fitting that the architect dreamt up a fueling station to support sprawl. This particular design dates back to 1927 and was originally planned for a corner of Michigan Avenue and Cherry Street in Buffalo, New York. While the project never came to life during Wright’s time, in 2014 the Buffalo Transportation Pierce-Arrow Museum realized Wright’s dream and constructed the station as a one-of-a-kind installation housed in a 40,000-square-foot glass and steel atrium. The arts-and-crafts gas station also offers a nod to Native American design and perfectly embodies the architect’s modernist spirit.

[Read more about the fueling station here]

Images © MoMA/Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

Images © MoMA/Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

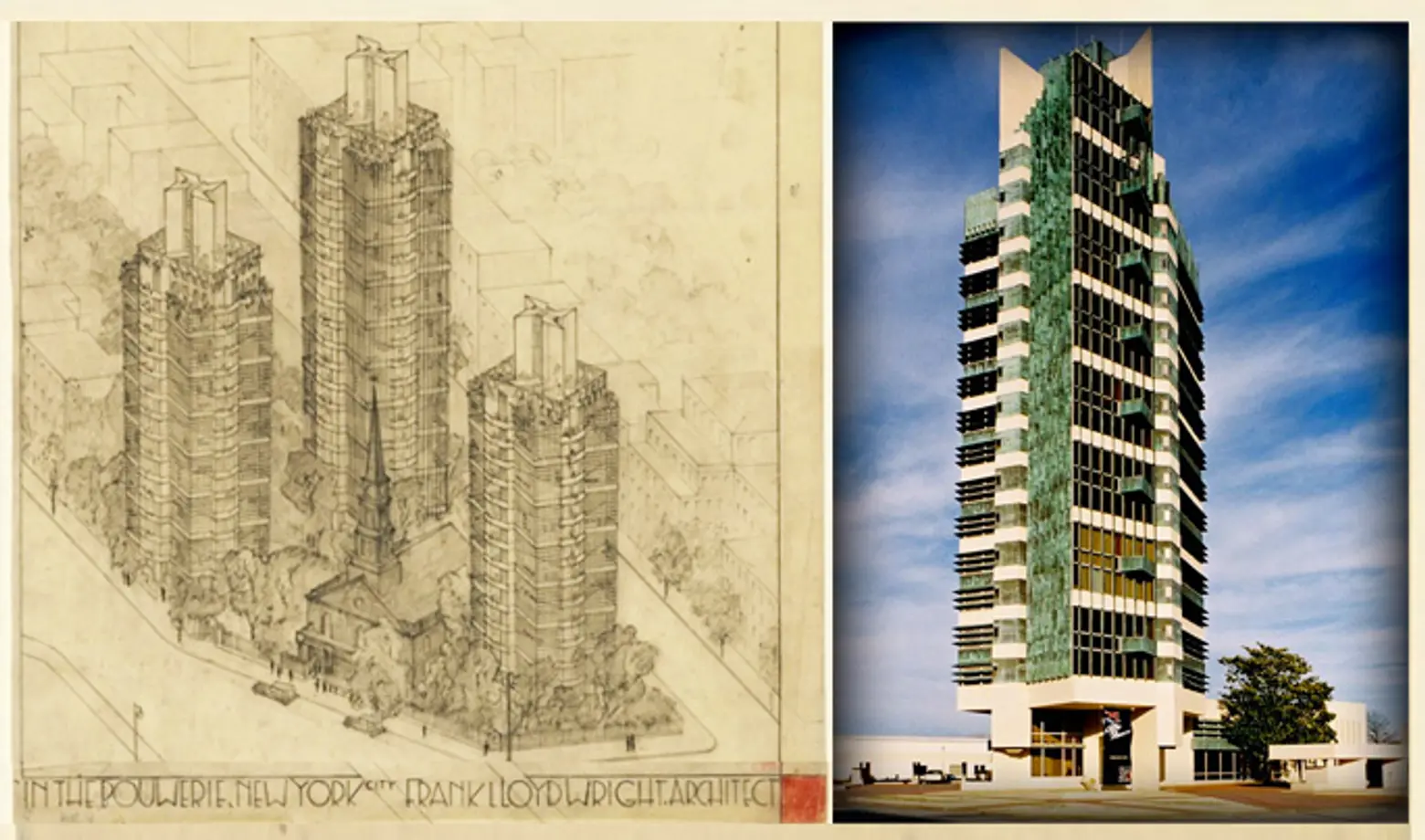

ST. MARK’S-IN-THE-BOUWERIE TOWERS: NEVER BUILT

Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1929 design for a set of skyscrapers surrounding St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery is an exercise in bringing nature into the city. Like the opponents of supertalls today, Wright hated how skyscrapers cast shadows on the landscape. As a way to maintain the light and bring greenery into our great city, he developed a plan for towers that would feature park space between. The skyscrapers were drafted in a typical Usonian design, but their height gave way to a new typology. At the time, this system was considered so striking that the press was quick to dub it “New York’s first all-glass building”—though the design is a far cry from the glass skyscrapers we know today. The towers were never constructed in Manhattan, but they did live on. A similar iteration has risen in Bartlesville, Oklahoma as an office building.

[Read more about these towers here]

RELATED: