Redeveloping NYC’s armories: When adaptive reuse and community building bring controversy

Park Avenue Armory, image © PBDW Architects

Constructed between the 18th and 20th centuries to resemble massive European fortresses and serve as headquarters, housing, and arms storage for state volunteer militia, most of America’s armories that stand today had shed their military affiliations by the later part of the 20th century. Though a number of them did not survive, many of New York City’s historic armories still stand. While some remain in a state of limbo–a recent setback in the redevelopment plans of Brooklyn’s controversial Bedford-Union Armory in Crown Heights raises a familiar battle cry–the ways in which they’ve adapted to the city’s rollercoaster of change are as diverse as the neighborhoods that surround them.

The Park Avenue Armory via Wiki Commons

Armories’ impenetrable construction and sheer size, with vast open drill halls and head houses, also qualify them for duty as emergency shelters during disasters like hurricanes and floods. During Hurricane Sandy in 2012, several of the city’s armories were called into duty once again as National Guard posts; others were used as temporary shelters for residents displaced by flooding. A number of the city’s armories function as homeless shelters. Some, like the New Balance Track and Field Center at the Fort Washington Armory, contain large and well-regarded sports facilities.

The well-known Park Avenue Armory–once called the Seventh Regiment Armory–in its early days hosted the National Guard as the first volunteer militia to respond to President Lincoln’s 1861 call for troops. Regiment members belonged to some of New York’s most prominent Gilded Age families. Built as both a military facility and a social club, the building’s interiors were designed by prominent designers and artists of the day including Louis Comfort Tiffany and Stanford White. A 55,000-square-foot drill hall remains one of the largest unobstructed spaces of its kind in the city.

Today, the well-regarded cultural venue offers season tickets to its cultural events which range from music to architecture and the celebrated Winter Antiques Show. Several recent renovations have kept the historic building in ship shape. But many more armories remain in a state of limbo.

The Bedford-Union Armory, Wiki Commons

The armory at the center of perhaps the most controversy is the Bedford-Union Armory that anchors part of a rapidly changing section of Brooklyn’s Crown Heights neighborhood. The armory occupies 138,000 square feet–nearly an entire block bounded by Bedford and Rogers Avenues and Union and President Streets. The neighborhood was the scene of well-known racial and cultural strife in the later part of the last century. Housing stock ranges from historic brownstones and former mansions in a sizable historic district to rows of pre-war apartment buildings, many of which remain rent-stabilized. Between the buildings, dozens of modern rental and condominium developments have sprouted, giving some blocks an old-meets-new feeling that’s becoming common in modern international cities. It’s the “new” part of that equation that makes battles that arise here so much more intense as the population of newcomers grows daily.

Built in 1903, the sprawling armory was first home to a National Guard cavalry unit. After World War I, it was used as a facility for tanks. It has been vacant since 2011; in 2013 the state ceded ownership to the city. The property immediately began attracting interest as a large-scale development with affordable and market-rate apartments, with office and community space.

Rendering of the Bedford Courts development planned for the Bedford-Union Armory; image: BFC Partners/Bedford Courts

The moment plans surfaced, the ambitious project–a joint effort of real estate developer BFC Partners and CAMBA, a Brooklyn-based nonprofit–became embroiled in local politics, with the city’s seemingly all-consuming gentrification fueling flames of mistrust and fear. The developers’ most current proposal, known as Bedford Courts, consists of 165 rent-regulated apartments set aside for households earning between 40 and 110 percent of the area median income, 12 condos for low- to middle-income residents, plus 165 rentals and 48 condos at market rate. The historic armory’s drill shed (at one time a cavalry exercise area) and head house would be restored to house a 67,752-square-foot recreational facility with basketball courts, a swimming pool, office space, and community event space.

Interior at the Bedford-Union Armory; image: Bedford Courts

Mayor Bill de Blasio, who has made affordable housing the cornerstone of his tenure, is a major force behind the redevelopment (the city’s Economic Development Corp. is overseeing the project). To proceed, the project must follow a process that involves all levels of local government followed by a City Council vote, and to make it a reality, the property would also have to be rezoned for more residential development and obtain a permit allowing the reuse of the historic armory. At the beginning of 2017, the city projected that if all went smoothly it could be complete by 2020. Of course, all has not gone smoothly.

As Politico reports, City Council member Laurie Cumbo (the property is in her district and her vote is needed to greenlight the project) recently announced her opposition to the armory redevelopment despite its backing by City Hall as a major win for affordable housing. Cumbo voiced approval for the project at first, but pressure from community activists like New York Communities for Change, a fair housing advocacy group, has led to her change in position. The opposition and community advocates feel the current plan does not include enough affordable housing and would rather see a completely below-market-rate development.

Advocates say adding more affordable units isn’t feasible due to the expense of constructing the huge recreational center and offering subsidized entry to the event space for community members since the project is not receiving any subsidies. “The economic realities of cross-subsidizing a new rec center and the lack of housing subsidies mean that 50 percent affordability is the only option currently available at the Armory,” said a spokesman for BDC. The city council vote, as yet unscheduled, will be the next step.

As the community struggles to meet in the middle, many of the parties involved raise good points. Meanwhile, the buildings sit vacant, though the project’s proponents are optimistic that an agreement will be reached that benefits everyone.

Bedford Atlantic Armory, Wiki Commons

A short distance down Bedford Avenue, the Bedford Atlantic Armory, built in the 1890s as the 23rd Regiment Armory, has been in use as the largest shelter for single men in the city since the early 1980s, With a capacity for 350 residents, it has been serving as an intake center and a gateway to the city’s homeless services such as treatment programs. With the appearance of a turreted castle rising almost menacingly over Bedford Avenue, the Romanesque Revival structure was designed to resemble the medieval military buildings of Europe with a series of circular corner towers reaching up to 136 feet high. However, the 2.3-acre complex, a city and national landmark, has been notorious for crime in the neighborhood.

In 2012, with property values climbing in the surrounding neighborhoods, the city announced plans for a $14 million redevelopment of the building’s 50,000-square-foot drill hall. Both the City Council and the Brooklyn borough president’s office weighed in with money and support.

A request for proposals brought talk of a project that included a recreational climbing facility, a concert hall or an ice skating rink. But the project stalled, and the homeless shelter remained. Several years later, the city determined that the armory’s massive drill hall could be crucial as an evacuation center following a natural disaster and that the existing shelter beds were needed more than other community facilities. It was also noted that the project’s would-be developers found that moving forward might prove to be too much of a financial challenge given the need to use the building as an emergency shelter.

Kingsbridge Armory in the Bronx, Wiki Commons

In the Bronx, another armory tells a completely different story, though no simpler and less ambitious in its execution. When it was constructed in the 1910s, the Kingsbridge Armory –also known as the Eighth Regiment Armory–was the largest armory in the world. Originally used for arms storage, then used by the city as a homeless shelter until 2006, the building has been on a path for redevelopment as the country’s largest ice skating complex led by New York Rangers captain Mark Messier and co-developer Ken Parker, partnered as the Kingsbridge National Ice Center (KNIC).

Rendering of the Kingsbridge National Ice Center via Facebook

Plans for the ice center originally included nine year-round ice rinks, one with seating for 5,000, and 50,000-square-feet of community space. Originally slated for completion in 2014, the redevelopment process has been fraught with complications and delays. However, Mayor de Blasio announced recently that the city’s Economic Development Corporation will return the property’s lease to the developers once they’ve secured a $108 million loan promised by Governor Cuomo as part of the state’s new annual budget, which may put the project back on track.

Eighth Avenue Armory in Park Slope, Wiki Commons

Faring better and adapting with comparative ease has been the Eighth Avenue Armory in Park Slope. Resembling a medieval castle, it boasts a barrel-vaulted 70,000-square-foot drill shed. Though some parts of the enormous building remain unused–like an old shooting range in the sub-basement and the officer’s club in the head house–in this 1893 building you’ll find the Park Slope Women’s Shelter as well as a large recreational facility operated by the Prospect Park YMCA that is available to local public schools. Also here is a military veterans’ museum that also provides space for veterans’ services from AA meetings to counseling and classes. The aforementioned drill hall served as an emergency shelter during Hurricane Sandy. Since the 1980s, the aforementioned non-profit organization CAMBA has operated the shelter; the building was renovated in 2007.

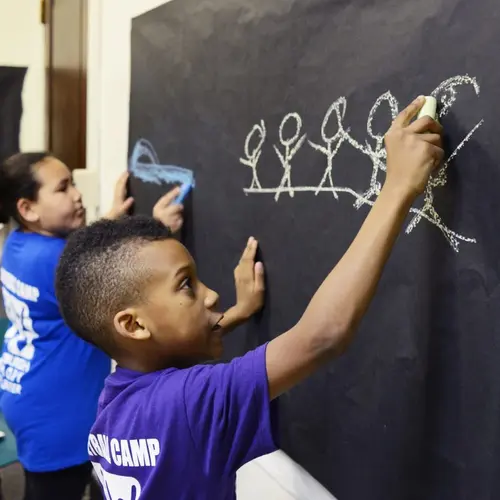

Community programs at the Newburgh Armory Unity Center.

Thriving armory conversions in other parts of the nation include some that are outside city limits. In sleepy Newburgh, NY, the Newburgh Armory Unity Center, a short stroll from the Hudson River, offers indoor and outdoor sports fields, a gymnasium, conference rooms, classrooms, a mobile office for the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, offices for an immigrant and refugee-focused wing of Catholic Charities, as well as services and advocacy non-profit Latinos Unidos.

This diverse mix is managed by a single nonprofit by the same name. The unique facility offers the community a place for recreation as well as an access and support resource for immigrants, refugees, and other community members. The sports facilities are intended to provide income from high-frequency rentals, creating a balance and sufficient income streams that are important when one organization is taking on all of the facility’s financial and management responsibilities. Without long-term commitment and steady cash flow, community-focused projects can flounder when faced with the inevitable managerial and construction challenges.

The San Francisco Armory

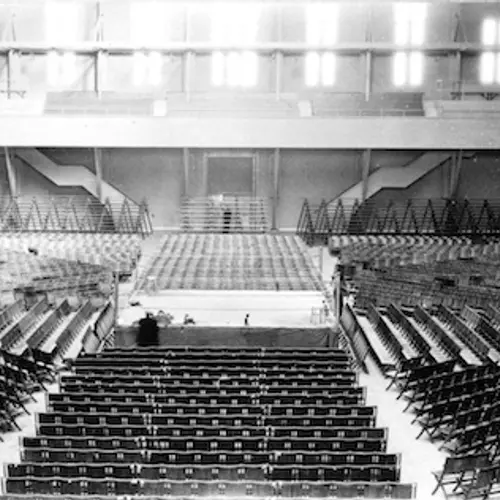

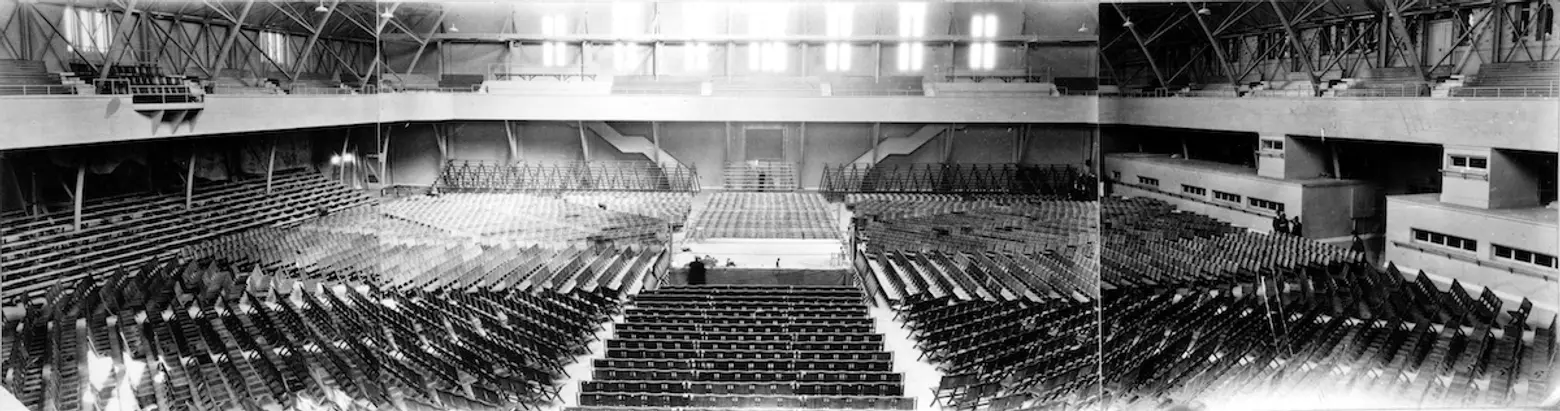

Interior of the drill court at the SF Armory, used as a boxing ring, ca. 1928.

The San Francisco Armory in the city’s Mission District was constructed for the National Guard in 1914, with its particular castle interpretation taking the form of a Moorish Revival style. In addition to its role as an armory and arsenal, from the 1920s to ‘40s it was the largest sporting events venue in San Francisco and often referred to as the “Madison Square Garden of the West,” famous for events like prizefights.

After the 1970s, the landmarked building was used only sporadically and fell into disrepair. Various uses proposed between 1996 and 2006 for the site included self-storage units, a rehab clinic, a gym with a rock-climbing wall, a dot-com office park, a telecommunications switching center, luxury housing and low-income housing. Not surprisingly, these proposals became mired in heated debates between community interests over gentrification, social and environmental impact. In 2006, the armory was purchased for $14.5 million by a San Francisco fetish pornography production company. More recently the same company angered neighborhood residents by proposing a music venue in the space. That chapter came to an end this year, however, when the porn studio closed its doors.

Many of these former fortresses have been spared the wrecking ball due to their historic status. They require significant and continuous financial backing and deep dedication to bring them into the 21st century in ways that are likely as unique as the communities that surround them. In observing the success stories, solutions can be found that will fortify those communities to withstand changing times and shifting fortunes.

More armory facts

- The Clermont Armory in Fort Greene is a rental residence, built on the site of one of the oldest armories in New York City. Located at 171 Clermont Avenue, apartments fill two wings behind the facade of the original armory. Three of the wrought iron trusses that spanned the original drill hall (built in 1873), were retained in the courtyard.

- The Park Avenue Armory was featured in scenes from the HBO’s “Boardwalk Empire. The space’s lavish interior appears as the Commodore’s mansion.

- The 69th Regiment Armory is one of the few in New York City that still houses its original regiment, the U.S. 69th Infantry Regiment (a.k.a. the Fighting Irish); it was also the site of the first Armory Art Fair.

RELATED:

- Renderings revealed for adaptive reuse Maker Park along the Williamsburg waterfront

- Governor Cuomo’s $1.4B Central Brooklyn plan stokes gentrification debate

- Governor Cuomo announces six investments to advance NYC’s outer boroughs

- Renderings, Details Revealed for Massive $1B Industry City Redevelopment in Sunset Park