Where I Work: Go inside Square Roots’ futuristic shipping container farm in Bed-Stuy

6sqft’s series “Where I Work” takes us into the studios, offices, and off-beat workspaces of New Yorkers across the city. In this installment, we take a tour of the Bed-Stuy urban farm Square Roots. Want to see your business featured here? Get in touch!

In a Bed-Stuy parking lot, across from the Marcy Houses (you’ll know this as Jay-Z’s childhood home) and behind the hulking Pfizer Building, is an urban farming accelerator that’s collectively producing the equivalent of a 20-acre farm. An assuming eye may see merely a collection of 10 shipping containers, but inside each of these is a hydroponic, climate-controlled farm growing GMO-free, spray-free, greens–“real food,” as Square Roots calls it. The incubator opened just this past November, a response by co-founders Kimbal Musk (Yes, Elon‘s brother) and Tobias Peggs against the industrial food system as a way to bring local food to urban settings. Each vertical farm is run by its own entrepreneur who runs his or her own sustainable business, selling directly to consumers. 6sqft recently visited Square Roots, went inside entrepreneur Paul Philpott‘s farm, and chatted with Tobias about the evolution of the company, its larger goals, and how food culture is changing.

Kimbal outside one of the farms

Kimbal outside one of the farms

Tell us how you got interested in and involved with the urban agriculture movement? And how did you and Kimbal start Square Roots?

I came to the U.S. from my native UK in 2003 to run U.S. operations for a UK-based Speech Recognition software company (i.e. a tech startup). I have a PhD in AI and have always been in tech. Through tech, I first met Kimbal Musk–he’s on the board of companies like SpaceX and Tesla–who at the time was setting up a new social media analytics tech company called OneRiot, which I joined him on in 2006.

Since then, Kimbal’s been working on a mission to “bring real food to everyone.” Even while I was working with him in tech, he had a restaurant called The Kitchen in Boulder, Colorado that sourced food from local farmers and made farm-to-table accessible in terms of menu and price point. His journey in real food started in the late ’90s, when he sold his first tech company, Zip2, and moved to NYC and trained to become a chef, his real passion. When 9/11 happened he cooked for firefighters at Ground Zero. It was during that time – where people would come together around a freshly cooked meal – that he began to see the power of real food and its ability to strengthen communities, even in the most awful conditions imaginable.

In 2009, while we were both working at OneRiot, Kimbal had a skiing accident and broke his neck. Realizing life can be short, he decided to focus on this idea of bringing real food to everyone. So he left OneRiot to focus on The Kitchen, which is now a family of restaurants across Chicago, Boulder, Denver, Memphis, and more. That organization ploughs millions of dollars into local food economies across the country by sourcing food from local farmers and giving its customers access to healthy, nutritious food. They also run a nonprofit, The Kitchen Community, that’s built hundreds of learning gardens in schools across the country, serving almost 200,000 school children a day.

After Kimbal’s accident, I became CEO of OneRiot, which was acquired by Walmart in 2011, where I ended up running mobile commerce for international markets. I learned a lot about the industrial food system there by working with huge data sets of the groceries people were buying across the globe and researching where those foods were being grown. I began to visualize food being shipped across the world, thousands of miles, before consumers bought it. It’s well known that the average apple you buy in a supermarket has been traveling for nine months and is coated in wax. You think you’re making a healthy choice, but the nutrients have all broken down and you’re basically eating a ball of sugar. That is industrial food. I left Walmart a year later and became CEO of an NYC photo editing software startup called Aviary, but I couldn’t get this map of the industrial food system out of my head. When Aviary was acquired by Adobe in 2014, I re-joined Kimbal at the Kitchen and we started developing the idea for Square Roots.

The campus was designed by local firm ORE

What we saw was that millions of people, especially those in our biggest cities, were at the mercy of industrial food. This is high calorie, low nutrient food, shipped in from thousands of miles away. It leaves people disconnected from their food and the people who grow it. And the results are awful – from childhood obesity to adult diabetes, to a total loss of community around food. (Not to mentioned environmental factors like chemical fertilizers and greenhouse gases.)

We also saw that these people were losing trust in the industrial food system and wanted what we call “real food.” Essentially, this is local food where you know your farmer. (This isn’t just a Brooklyn hipster foodie thing. Organic food has come from nowhere to be a $40 billion industry in the last decade. “Local” is the food industry’s fastest growing sector.)

Meanwhile, the world’s population is growing and urbanizing quickly. By 2050 there will be nine billion people on the planet, and 70 percent will live in cities. So if we have more people living in the city, demanding local food, the only conclusion you can draw is that we’ve got to figure out how to grow real food in the city, at scale, as quickly as possible. In many ways NYC is a template for what that future world will look like. So our thinking was: if we can figure out a solution in NYC, then it will be a solution for the rest of the world as it increasingly begins to look like NYC. The industrial food system is not going to solve this problem. Instead, this presents an extraordinary opportunity for a new generation of entrepreneurs – those who understand urban agriculture, community, and the power of real, local food. Kimbal and I believe that this opportunity is bigger than the internet was when we started our careers 20 years ago.

So we set up Square Roots as a platform to empower the next generation to become entrepreneurial leaders in this real food revolution. At Square Roots, we build campuses of urban farms located in the middle of our biggest cities. The first campus is in Brooklyn and has 10 modular, indoor, controlled climate farms that can grow spray-free, GMO-free, nutritious, tasty greens all year round. On those farms, we coach young passionate people to grow real food, to sell real food, and to become real food entrepreneurs. Square Roots’ entrepreneurs are surrounded and supported by our team and about 120 mentors with expertise in farming, marketing, finance, and selling–basically everything you need to become a sustainable, thriving business.

Why did you choose to set up at Bed-Stuy’s Pfizer Building?

We believe in “strengthening community through food,” and hopefully by joining forces with all the awesome local food companies already in Pfizer, we’re doing our part towards that. Next, in the lead up the first World War, that factory was the U.S.’s largest manufacturer of ammonia, which at the time was used for explosives. Post war, the U.S. had excessive amounts of ammonia, and it started being used as fertilizer. So in many ways, that building is the birth place of industrial food. I like the act of poetic justice that we now have a local farm on the parking lot.

Paul Philpott’s company is called Gateway Greens. His membership-based business model is that his members pay a premium to subsidize food for low-income New Yorkers.

Paul Philpott’s company is called Gateway Greens. His membership-based business model is that his members pay a premium to subsidize food for low-income New Yorkers.

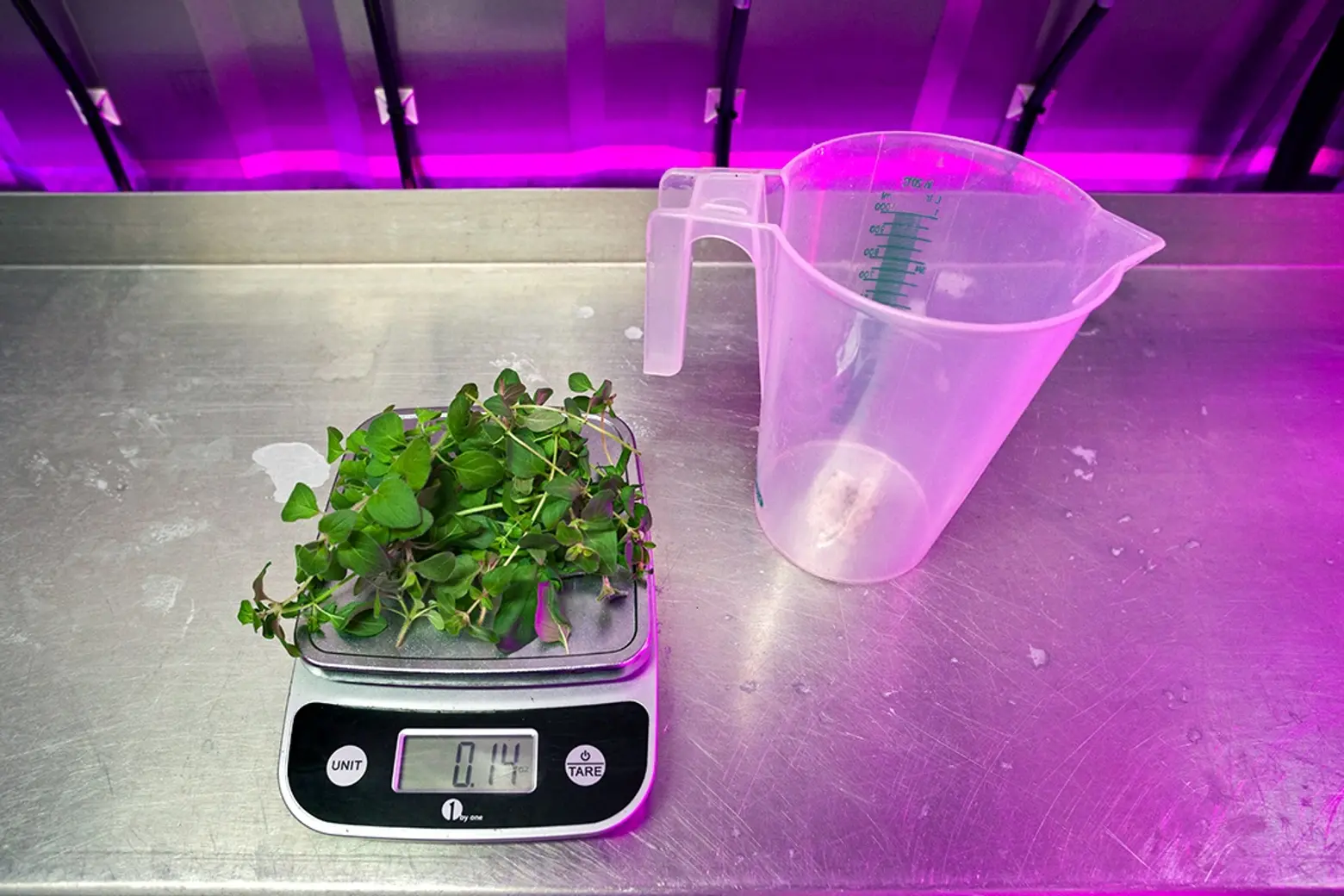

He grows oregano, parsley, sage, thyme, and cilantro, as well as swiss chard, collard greens, and kale.

He grows oregano, parsley, sage, thyme, and cilantro, as well as swiss chard, collard greens, and kale.

You received more than 500 entrepreneur applications; how did you narrow it down to just 10?

Lots of late nights watching video applications! We were looking for people with shared values and mission – a belief in the power of real, local food. And we needed to see a passion for entrepreneurship. Being an entrepreneur in Square Roots is hard and we needed to make sure that first 10 were coming in with eyes wide open. They are really kicking ass now!

Each farm can produce 50,000 mini-heads of lettuce per year.

Each farm can produce 50,000 mini-heads of lettuce per year.

The greens are grown hydroponically, meaning the nutrients are mixed with the water that feeds the roots, since the system is soil-free and uses LED lights. Each farm uses about 10 gallons of water a day–less than a typical shower.

The greens are grown hydroponically, meaning the nutrients are mixed with the water that feeds the roots, since the system is soil-free and uses LED lights. Each farm uses about 10 gallons of water a day–less than a typical shower.

For someone who’s not familiar with this type of technology, can you give us a basic rundown of how it works and compares with traditional farming?

The first thing we’ve got to do is build farms in the middle of the city. In Bushwick, these are modular, indoor, controlled climate, farms. You can put them in the neighborhood right next to the people who are going to eat the food. To set this up, we literally rent spaces in a parking lot and drop the farms in there. It’s scrappy, but they enable year-round growing and support the annual yield equivalent of two acres of outdoor farmland inside a climate-controlled container with a footprint of barely 320 square feet. These systems also use 80 percent less water than outdoor farms. That’s the potential for a lot of real food grown in a very small space using very few resources. Each of our ten farms is capable of growing about 50 pounds of produce per week. Most of that today goes to customers of the Farm to Local program, where a local farmer will deliver freshly harvested greens direct to your office (people love having a farmer show up at their desk with freshly harvest greens right before lunch!) Some of the farmers sell to local restaurants also.

Why do you think consumers in general respond so well to this type of local farming?

This generation of consumers want food you can trust, and when you know your farmer, you trust the food. There are so many layers between the farmer and the consumer in industrial food–agents, manufacturers, wholesalers, retailers, the list goes on. And every one of them takes their cut, leaving the farmer with paper thin margins and the consumer with no connection to the food or the people who grow it. That’s 20th century food, where it takes weeks to get to you and the food has to be grown to travel. Square Roots farmers can harvest and deliver within hours – meaning food is grown for taste and nutrition.

Moving forward, how do you hope urban farming will coincide with more traditional agriculture?

The consumer wants local food where they know the farmer and the food tastes great. Whether that’s grown on a no-till organic soil farm or in a container on a parking lot, if it’s local food it’s food you can trust – and we’re all on the same side. The common enemy here is industrial food.

Where do you hope Square Roots will be in a year from now? What about 10 years?

We grow a ton of food in the middle of the city and sell locally. So we see revenue from direct-to-consumer food sales and we’re building a very valuable local food brand. But as we replicate campuses and our program to new cities, we’re building that local food brand at a national and then ultimately global scale. At the same time, our model unleashes an army of new real food entrepreneurs who will graduate from Square Roots and start their own amazing businesses, who we will invest in.

I’ve been quoted on this before, but I’d like to think I can open Fortune Magazine in 2050 and see a list of Top 100 Food Companies in the world, which includes Square Roots and 99 others that have been started by graduates of Square Roots, who all share our same values. That would mean we’re truly bring real food to everyone.

+++

All photos taken by James and Karla Murray exclusively for 6sqft. Photos are not to be reproduced without written permission from 6sqft.