How Aaron Burr gave the city a faulty system of wooden water mains

In 2006, construction crews discovered a 13-foot section of the wooden water mains under Beekman Street near the South Street Seaport, photo courtesy of Chrysalis Archaeology

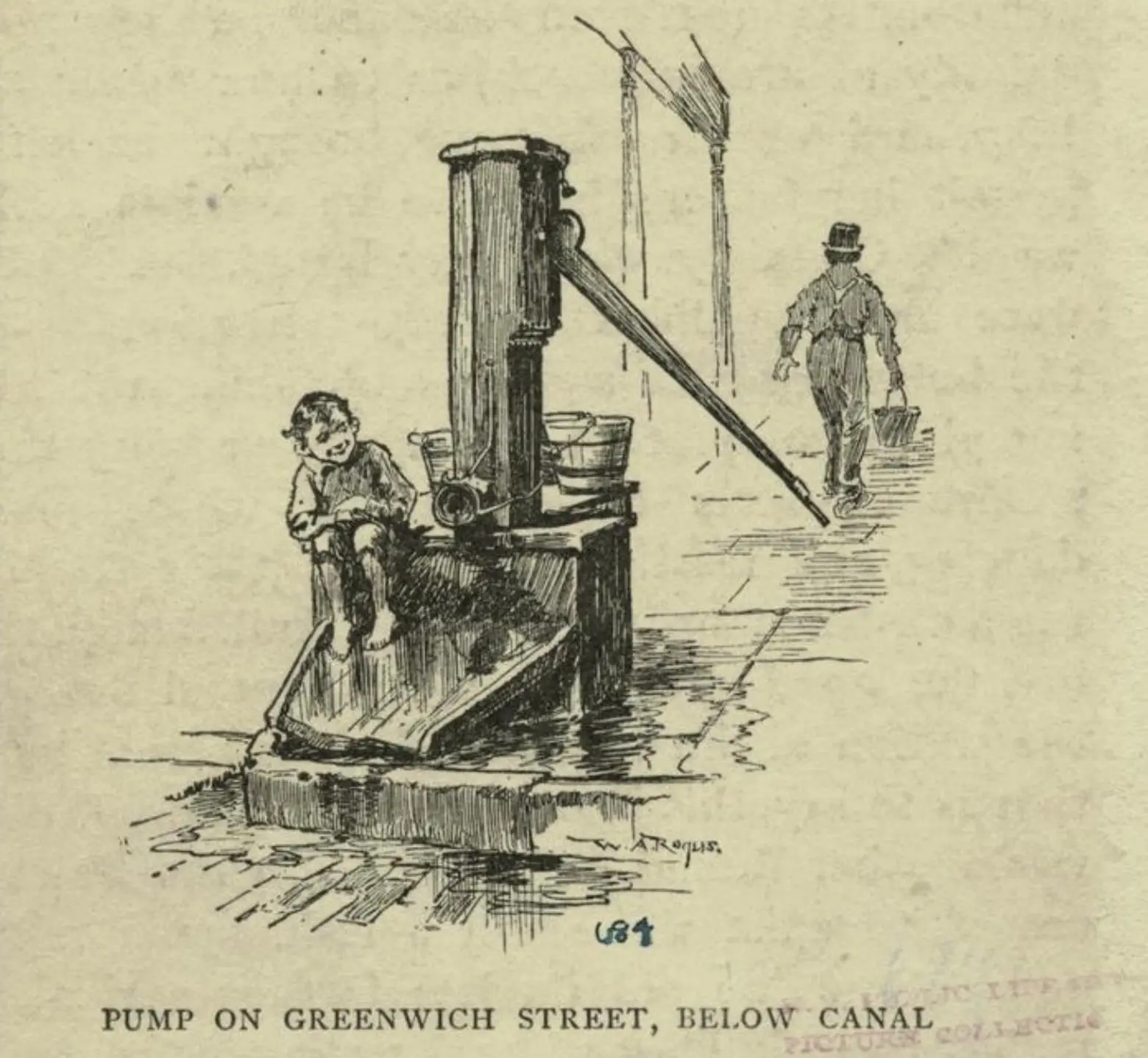

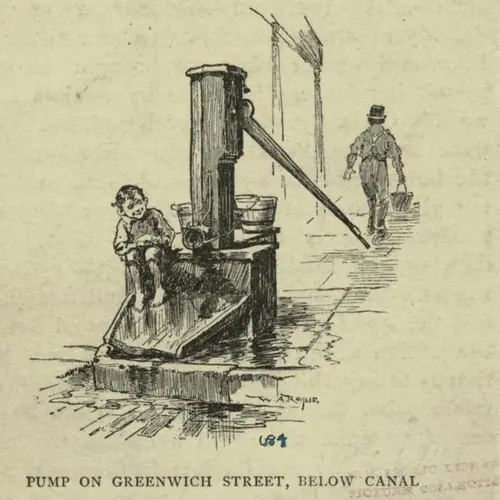

At the turn of the 18th Century, New York City had a population of 60,515, most of whom lived and worked below Canal Street. Until this time, residents got their water from streams, ponds, and wells, but with more and more people moving in, this system became extremely polluted and inefficient. In fact, in the summer of 1798, 2,000 people died from a yellow fever epidemic, which doctors believed came from filthy swamp water and led the city to decide it needed a piping system to bring in fresh water. Looking to make a personal profit, Aaron Burr stepped in and established a private company to create the city’s first waterworks system, constructing a cheap and ill-conceived network of wooden water mains. Though these logs were eventually replaced by the cast iron pipes we use today, they still live on both under and above ground in the city.

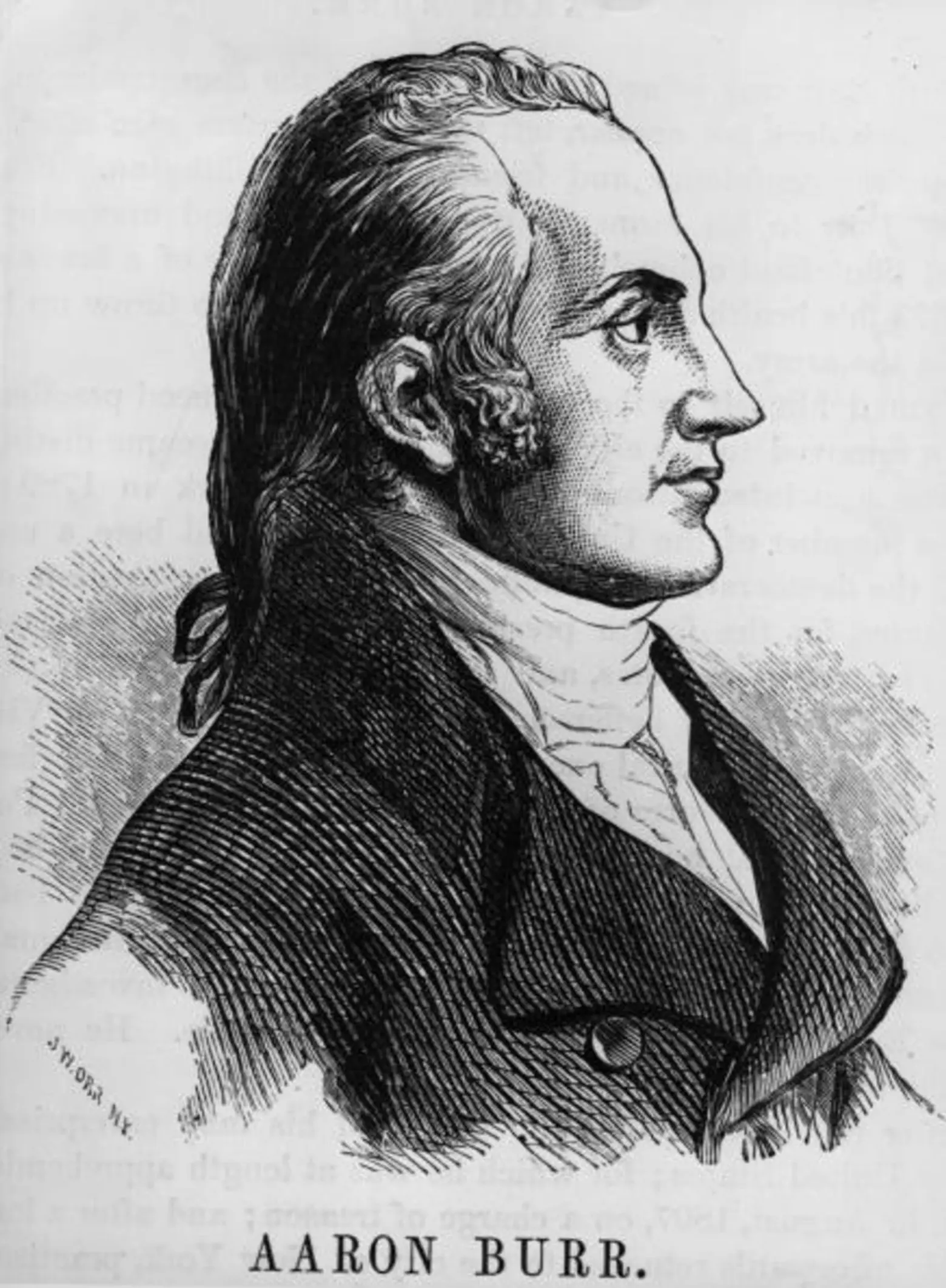

In 1799, State Assemblyman Aaron Burr convinced the city and state to create a private company to supply the city “with pure and wholesome water.” He then snuck in a provision that his newly formed Manhattan Company could use surplus capital for business purposes as long as they weren’t inconsistent with state and federal laws. Burr, a Democratic-Republican, had a secret motive to establish a bank to compete with Alexander Hamilton’s Bank of New York and the New York branch of the First Bank of the United States, both run by the Federalist party. Later that year, he did just that, opening the Bank of the Manhattan Company at 40 Wall Street (it would later become JP Morgan Chase).

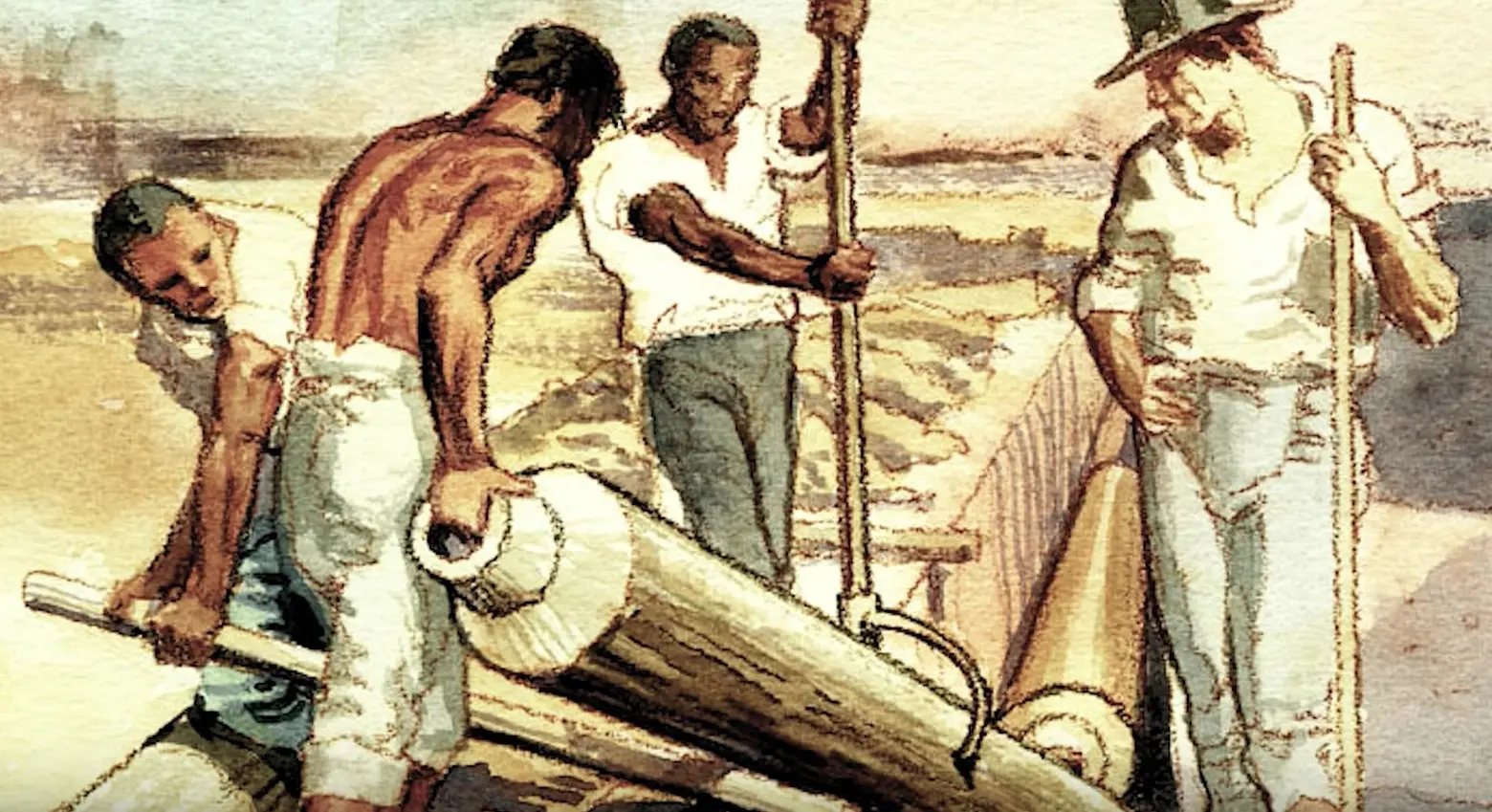

The Manhattan Company next began their waterworks venture, building a small reservoir on Chambers Street to source water from wells below Canal Street and Collect Pond, a 48-acre fresh water pond at the current intersection of Mott and Grand Streets. They constructed a disorganized system of wooden pipes to take the water from the reservoir to New Yorkers. Using an auger, they cored out yellow pine logs with the bark intact, tapering one end to fit them together, fastened by wrought iron bands.

However, the system was plagued with problems, not surprising considering Burr’s main goal was to pocket funds. The pipes had low pressure, froze in the winter, and were easily damaged by tree roots. Plus, since Burr decided to only source water from Manhattan (even though he was given permission to go outside and get known clean water from the Bronx River), the supply was polluted from years of industrial, animal, and human runoff.

Despite the fact that most other U.S. cities made the shift to cast iron pipes in the 1820s, the Manhattan Company continued to lay wooden pipes and remained the only supplier of drinking water until 1842, at which time the Croton Aqueduct first brought water from upstate to Central Park through cast iron water mains.

In 2006, during a project to replace Department of Environmental Protection water mains and other utilities near the South Street Seaport, two of the 200-year-old wooden pipes were discovered four feet below ground along the stretch of Beekman Street between Water and Pearl Streets. They measured 12 and 14 feet in length with a 2.5-foot circumference and 8-inch center holes. Amazingly, they were completely intact and still connected.

The DEP brought on Chrysalis Archaeology to clean the logs, stabilize the deteriorating wood and prevent it from further decay, and reattach pieces of the original bark. The wooden mains sat in the DEP’s headquarters for several years before they brought to the New-York Historical Society and added to a display near an 1863 Civil War draft wheel and George Washington’s cot. Learn more about this endeavor in the video below:

RELATED: