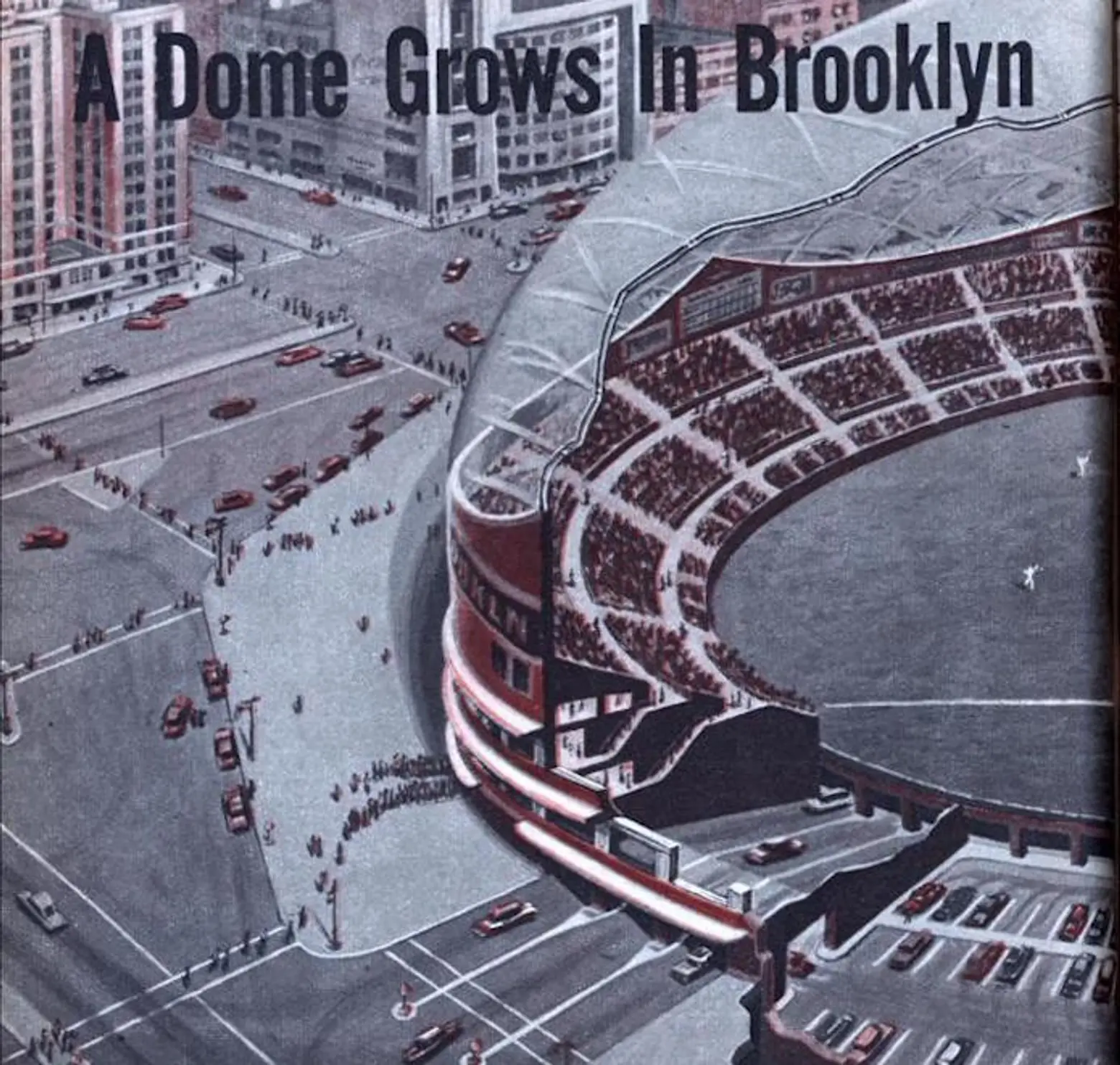

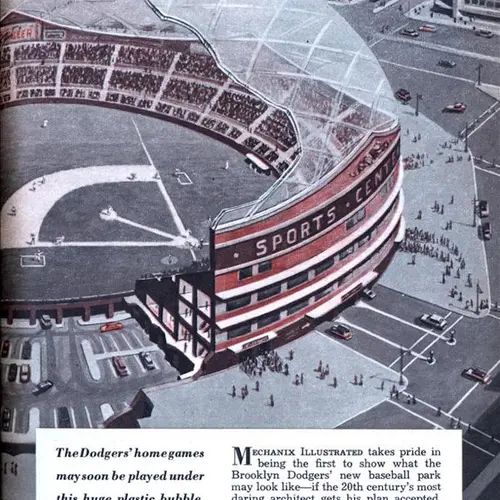

A Buckminster Fuller dome almost kept the Dodgers in Brooklyn

With baseball season back in full swing, talk at some point turns to the heartbreak of losing the Brooklyn Dodgers to Los Angeles. Modern Mechanix informs us that team owner Walter O’Malley had championed a Brooklyn dome stadium designed by Buckminster Fuller–and how the result is yet another reason to blame Robert Moses. O’Malley took the team to Cali, if you’ll remember, because he got a better deal on land for a stadium–better than he was able to get in the five boroughs. He had wanted to keep the team in Brooklyn, but Ebbets Field was looking down-at-the-heels by then and bad for morale. In 1955 O’Malley wrote dome-obsessed architect Buckminster Fuller requesting a domed stadium design.

Photo: Modern Mechanix

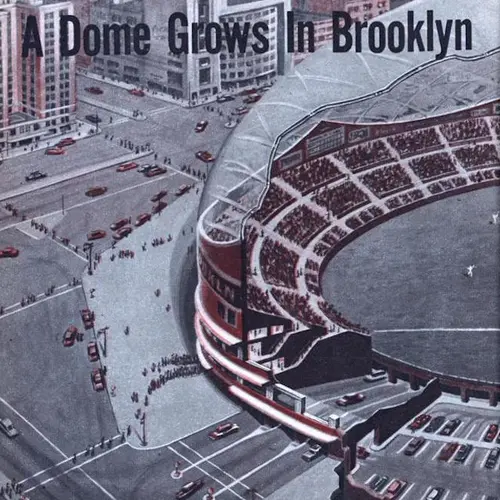

Fuller obliged, and, though his later Manhattan dome proposal is often associated with the futuristic or the farfetched, O’Malley called the architect’s stadium dome design “quite practical and economical,” so much so that state legislators were convinced it would be able to pay for itself. The dome, which would have been designed with assistance from Fuller’s Princeton University School of Architecture graduate students, was to be situated where the Atlantic Terminal Mall and Barclays Center are today, on a four-square-block area around Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues.

Houston’s Astrodome was still a decade in the works, so the dome would have been a first, at 300 feet high and 750 feet in diameter, with air venting, shadowless lighting fixtures, an underground parking lot and a promenade with shops and restaurants. It would have cost $6 million to construct and would have been privately financed.

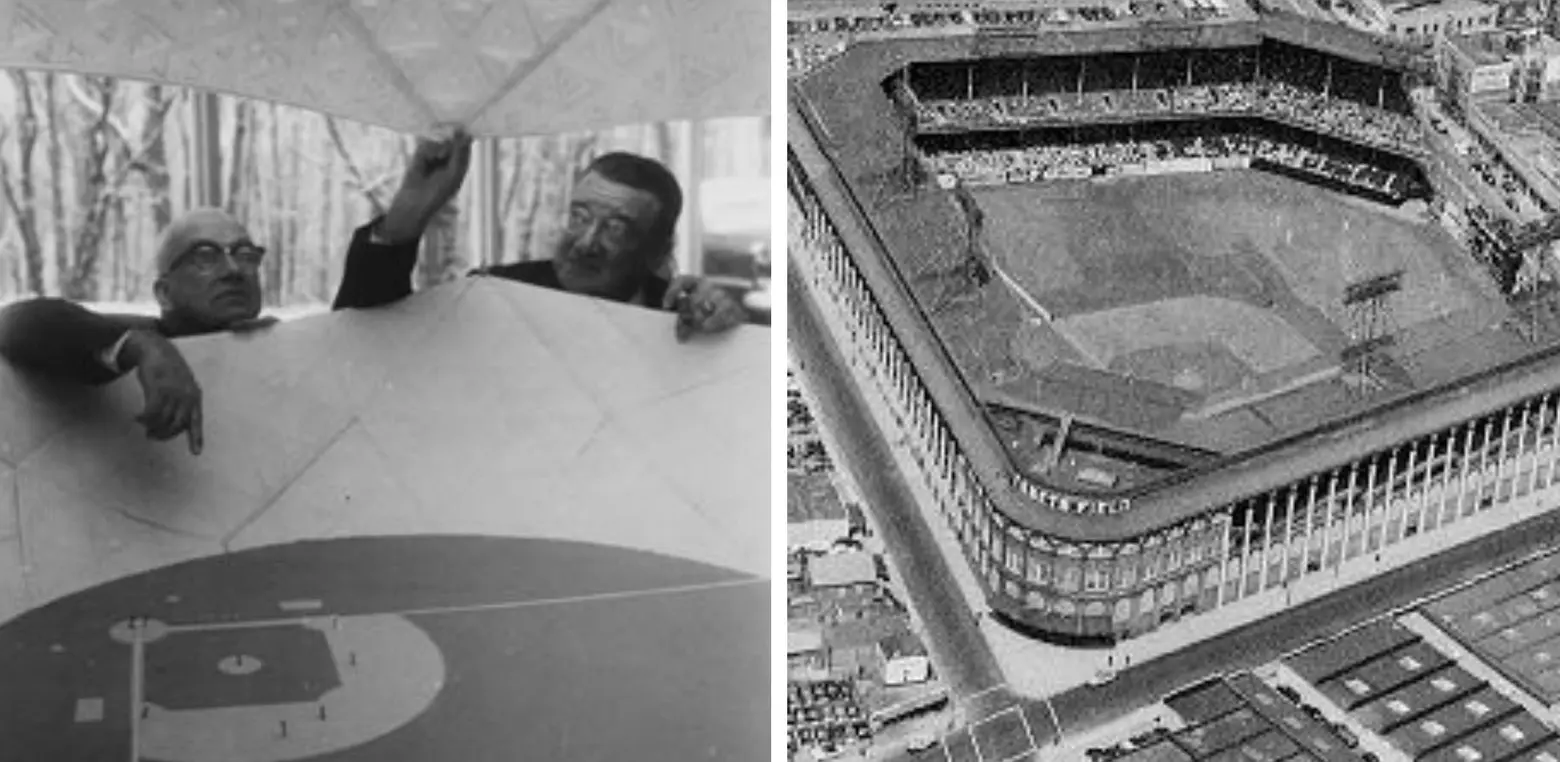

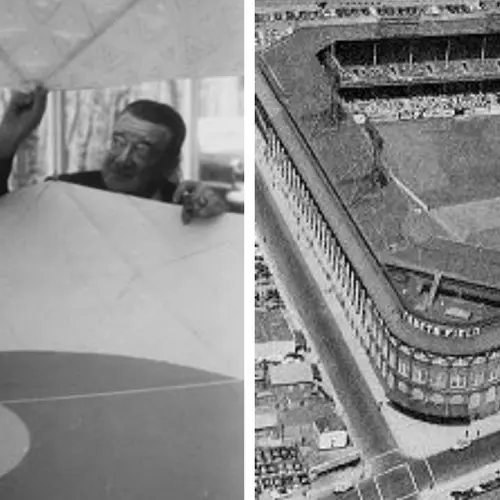

Walter O’Malley and Buckminster Fuller examine the model for the stadium in November 1955; Ebbets Field (right)

According to Modern Mechanix, “The dome design makes feasible the demand for a ball park big enough to hold the enormous Dodger following. It would also be an all-weather, year-round sports palace capable of pulling in big money as a showplace for every kind of sporting event and exposition.” The state legislature “created a $30,000,000 authority empowered to create such a center.”

So where does Robert Moses butt in? As a powerful influence on development, he happened to be the one person whose backing O’Malley needed. Around the same time, Moses had proposed a stadium for the team in Flushing Meadows, Queens (where Shea Stadium ended up being built). He was dead-set against a stadium in downtown Brooklyn, saying that it would “create a China Wall of traffic.”

Robert Moses with a Battery Bridge model.

O’Malley reportedly told Moses, “If my team is forced to play in the borough of Queens, they will no longer be the Brooklyn Dodgers.” The two had a well-documented debate on the subject, never getting beyond what the press called a “scoreless tie.”

Sadly, the dome never progressed beyond its preliminary design stage. Reportedly, although O’Malley had lined up political support–including that of New York Governor W. Averell Harriman–Moses blocked the sale of the land necessary for the planned new Brooklyn stadium, and when L.A. came calling with land at the Chavez Ravine and the ability to own and control all revenue streams–Moses’s Queens proposal would have been a municipal stadium–the offer was too good to refuse. The Dodgers played their last Brooklyn game on September 24th, 1957–and their first Los Angeles game on April 18th, 1958.

[Via Modern Mechanix]

RELATED:

Get Insider Updates with Our Newsletter!

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

I may have commented on this when the article was posted a few months ago (sorry if I’m repeating) but there were two designs, the one featured in this post, and a more refined version by Fuller with a sunken playing field and more exciting dome over pillars. I illustrated that one for the cover of Brooklyn Bridge Magazine, the May 1997 issue. Coulda Woulda Shoulda.