An Architect’s Gift from the Jet Age: The TWA Flight Center at JFK International Airport

Photo courtesy of Beyer Blinder Belle

The TWA Flight Center at what is today John F. Kennedy International airport represents both the ephemeral and the ageless; our vulnerability at the end of the “American century” and the enduring beauty of inspired modern design.

The work of mid-20th century Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen, the historic terminal is among the city’s most beloved architectural treasures. It first opened in 1962, a year after the architect’s death, and Saarinen posthumously received the AIA Gold Medal award for the design in 1962.

Despite its storied past and widespread reverence, since the demise of TWA and its subsequent purchase by American Airlines in 2001, the terminal’s iconic “head house” has remained eerily vacant, and its future continues to be a point of contention.

TWA Flight Center, departures hall information desk; By DearEdward via Wikimedia Commons.

TWA Flight Center, departures hall information desk; By DearEdward via Wikimedia Commons.

When Eero Saarinen died suddenly at the age of 51, he was one of America’s most celebrated architects. He had been able to capture an “American moment” incorporating both the clean, modern lines of the International Style and the familiarity and warmth of Frank Lloyd Wright.

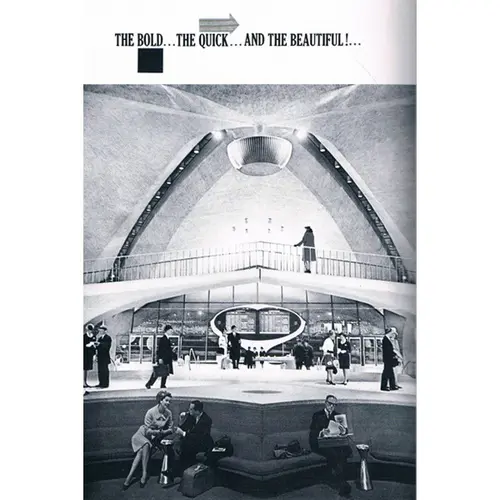

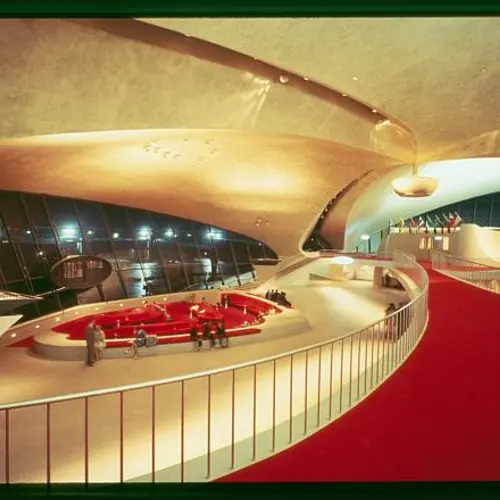

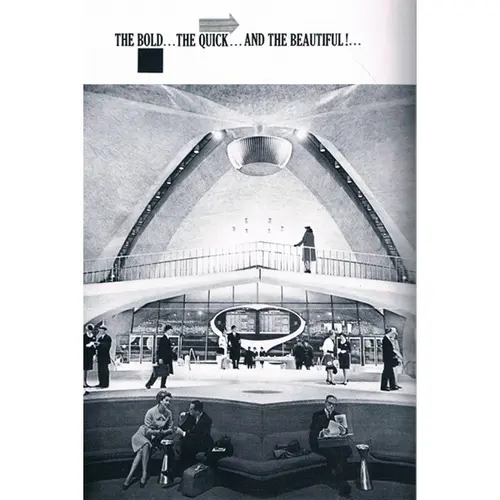

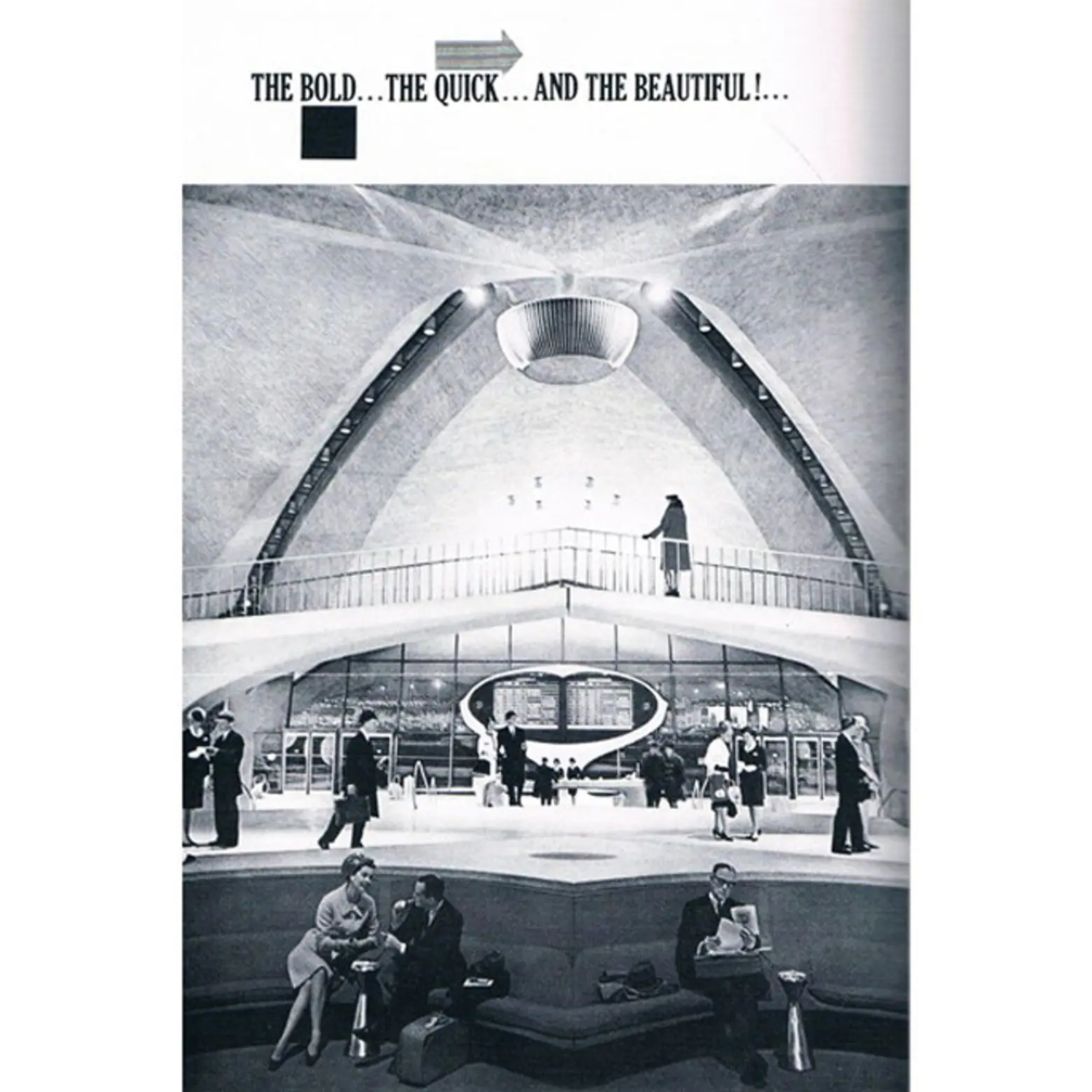

In designing the TWA terminal, the challenge was to evoke the drama, excitement and romance of travel in the structure itself. Perhaps the first thing observers notice in Saarinen’s neo-futurist design is the wing-shaped “thin shell” roof above the main terminal or head house; tube-shaped arrival and departure corridors were lined in lush red carpet; spacious windows afforded front-row views of departing and arriving jets, as did the interior’s many balconies and landings.

A vast sunken lounge offered a crimson leather banquette in front of a huge picture window. Travelers scanned futuristic oval-shaped arrival and departure screens to determine their next adventure. Leonardo DiCaprio was filmed here in dapper ’60s pilot’s gear for scenes in the fanciful true story, Catch Me If You Can.

A scan from Fly the Finest Fly TWA: A Pictorial History of Trans World Airlines, 1925-1987 by Fathom Way To Go

A scan from Fly the Finest Fly TWA: A Pictorial History of Trans World Airlines, 1925-1987 by Fathom Way To Go

Futuristic design, real innovation

The terminal’s design was more than fantasy; it was among the first to offer enclosed passenger jetways, closed circuit television, a central PA system, baggage carousels and electronic arrival and departure boards. The satellite arrangement of gates away from the main terminal was an innovation as well. Elegant food and beverage choices included the Constellation Club, Lisbon Lounge, and Paris Café.

Cafe in the TWA Flight Center at JFK Airport; photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Cafe in the TWA Flight Center at JFK Airport; photo via Wikimedia Commons.

A prolific architect and designer, Eero Saarinen also designed the St. Louis Gateway Arch, the Knoll-manufactured “Tulip” table and chairs, the main terminal at the Dulles International Airport in Washington, D.C., the CBS Building and the Vivian Beaumont Theater at Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts in New York City, among many other well-known designs. He had been awarded numerous prestigious commissions to design modern corporate headquarters and research hubs for corporations like General Motors, IBM and Bell Telephone, to name just a few.

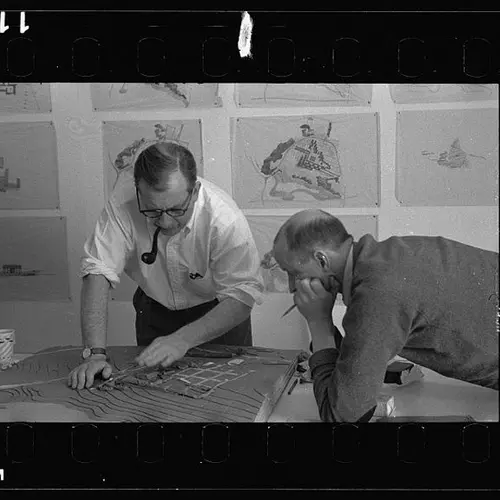

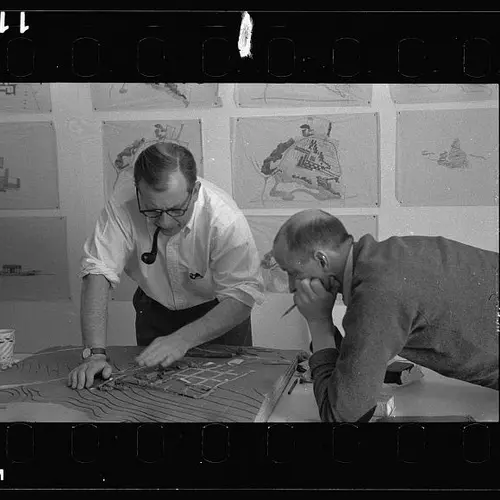

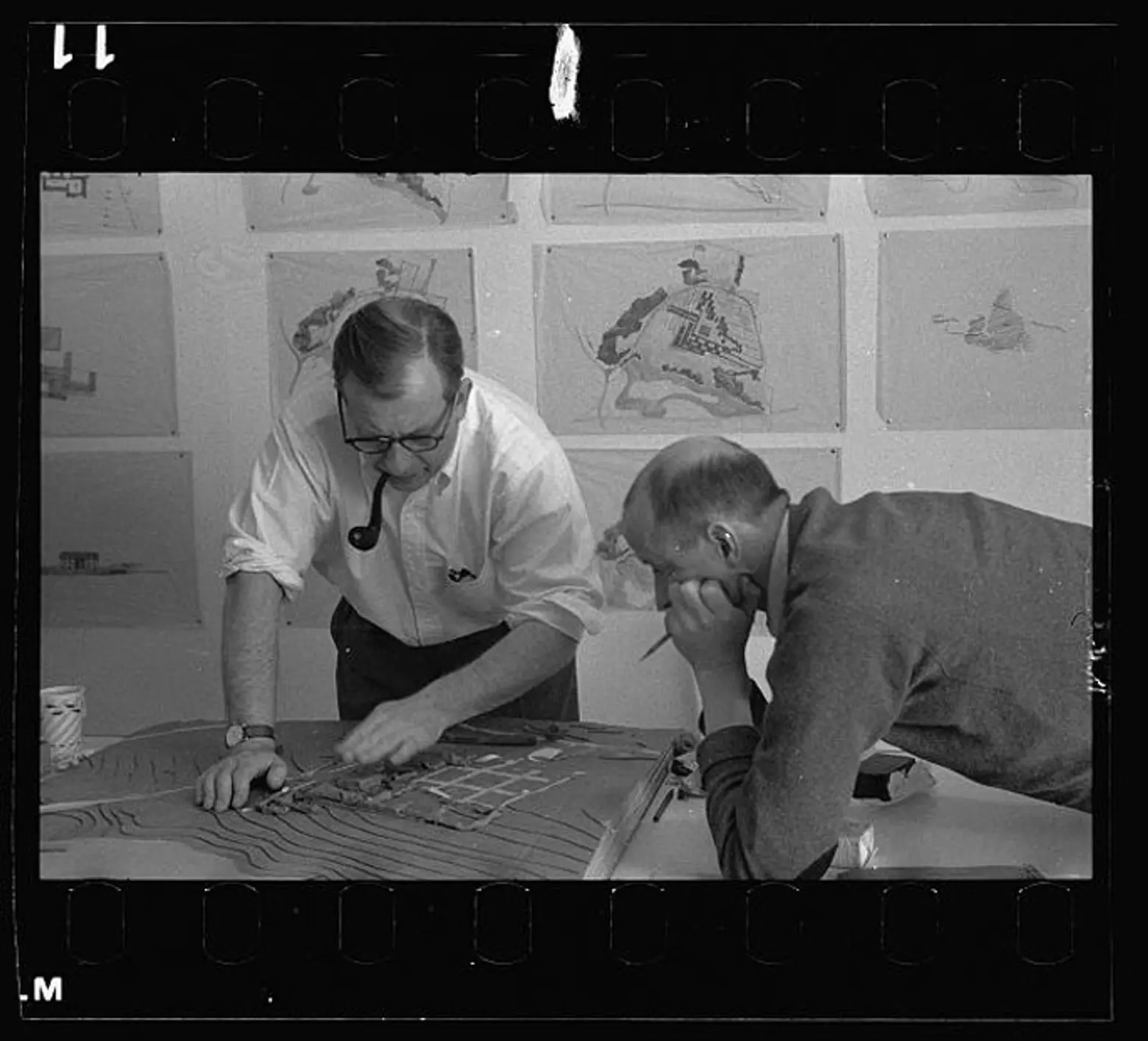

Eero Saarinen (left) and Kevin Roche at the office in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. Photo courtesy of Balthazar Korab Archive at the Library of Congress.

Eero Saarinen (left) and Kevin Roche at the office in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. Photo courtesy of Balthazar Korab Archive at the Library of Congress.

These projects, in a way, tasked the architect with the job of creating a unique American style for the postwar era. In 1956, Saarinen’s portrait appeared on the cover of Time magazine; the article within declared America the new world leader in contemporary design.

Saarinen believed that modern architecture could be improved by bringing back the concept of customized design. Seen by some as the “go-to modernist of the postwar building boom,” he was versatile in meeting the needs of corporate America in addition to being innovative. This divergence from the rigors of modernist architecture of the day was considered suspect by some critics: Were his designs too slick? Was he too much of a Madison Avenue accomplice? Did his designs aid the modern corporate concept of “planned obsolescence?”

The terminal vs. time: Fantasy, modernity, reality

Almost as soon as the terminal opened, the jumbo jet era dawned, bringing with it increased passenger traffic and increased security requirements. Accommodating these new demands were made difficult by the building’s design; the terminal gates were near the street, also making centralized ticketing and security difficult. Nonetheless, in the ensuing decades of its heyday, the terminal embodied the glamour of air travel for millions who passed through its gates.

Exterior: wallyg via photopin cc; Interior: gabriel.jorby via photopin cc

Exterior: wallyg via photopin cc; Interior: gabriel.jorby via photopin cc

TWA declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy between 1992 and 1995. Subsequent plans for the building included a conference center, nixed by an outcry from architects and preservationists because it would have involved building a structure which would obscure the original. The City of New York designated the building an historic landmark in 1994; in 2005 it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Restoring a landmark

Renowned architecture firm Pei Cobb Freed & Partners submitted plans for a renovation in 1990 which called for a central receiving terminal with a subway station underneath and connections to flight terminals via radiating “people movers;” the Port Authority deemed the design too impractical and costly to build. The architecture firm of Beyer Blinder Belle, who have been consultants on the project since 1994, removed asbestos and extensively renovated many parts of the structure. This careful renovation considered everything from the details of each circular tile to the painstaking sourcing of materials from all over the globe.

More history to be made

In the 21st century, innovative airline Jet Blue chose the 20th century icon for its terminal hub. Rockwell Group and Gensler redesigned the building for Jet Blue in 2008, the first comprehensive new terminal to be constructed since September 11, 2001. The airline’s Terminal 5 (known as “T5”) abuts the building and borrows its clean, modern interior aesthetic, but the entryway to Saarinen’s head house was not made part of the new terminal; portions of the original complex were demolished.

Though Port Authority of New York & New Jersey is hoping for a complete renovation, the iconic main building remains deserted. Proposals for the space have included the aforementioned conference center, an aviation museum, a restaurant and a hotel, all of which have broken down in the discussion phase. Most recently, high-profile hotelier André Balazs (of hip Standard hotels fame) announced plans to make the space into a hotel and conference center with food and beverage outlets, retail, a fitness center and a flight museum. Why is this such a tough spot to fill? Reasons have run the gamut from design challenges to union concessions; Late-stage talks between the Port Authority and Balazs on the creation of a 150-room hotel have since been abandoned.

According to architecture critic Alexandra Lange, who has written on the subject for Design Observer, “the reasons two RFPs have failed and they are on their third are various. The first time around, the winning bidder was going to have to clean up the asbestos and restore the Saarinen building as part of the project, and no one wanted to take that on. Then the PA did that as a separate project.”

TWA Terminal, JFK Airport, Model; photo courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Balthazar Korab Archive at the Library of Congress.

TWA Terminal, JFK Airport, Model; photo courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Balthazar Korab Archive at the Library of Congress.

She believes that the appeal to modern hoteliers, for example, may be limited by landmark status restrictions, making it hard to adapt the building without destroying the setting: “You need a developer who is in love with the idea of reviving that building, and an architect who understands the style and milieu and can respect it.” As far as her visions for the space, “If JFK had better transit connections to Manhattan and western Brooklyn and Queens it could be a destination bar, but that, I think, is its biggest problem as a long-term and non-touristy event space.”

Lange also says, “I love the TWA terminal, and I love that the PA wants it to become a living, breathing, active place again. I don’t believe in making historic architecture into a museum, and I am thankful that the TWA building has enough fans that it won’t disappear in the night. This month, a new call for proposals was announced, with potential ground lease offering terms as long as 75 years.

By any standards, the architect’s glamorous American modernism, expressed in his many enduring iconic designs–from his “Tulip” chairs to the Gateway Arch–remains timeless and continues to inspire. There is sadness in the idea of such a modern masterpiece sitting empty and unused, but also triumph in its achievement of the recognition it deserves and in the talent and innovation of those that have worked to update it for a new century. What is needed now is an idea and a commitment to the effort it will take to bring an icon of modernist design into the future.

Armchair architects: What are your fantasies and suggestions for how to use this landmarked modernist masterpiece in the 21st century.

Sources: Design Observer: “Modern Architecture for the American Century“; Untapped Cities: “Behind the Scenes at the TWA Flight Center at JFK Airport“