Behind the scenes at the United Palace, Washington Heights’ opulent ‘Wonder Theatre’

Earlier this year, 6sqft got an exclusive behind-the-scenes tour at the Loew’s Jersey City, one of the five opulent Loew’s Wonder Theatres built in 1929-30 around the NYC area. We’ve now gotten a tour of another, the United Palace in Washington Heights. Originally known as the Loew’s 175th Street Theatre, the “Cambodian neo-Classical” landmark has served as a church and cultural center since it closed in 1969 and was purchased by televangelist Reverend Ike, who renamed it the Palace Cathedral. Today it’s still owned by late Reverend’s church but functions as a spiritual center and arts center.

Thanks to Reverand Ike and his church’s continued stewardship, Manhattan’s fourth-largest theater remains virtually unchanged since architect Thomas W. Lamb completed it in 1930. 6sqft recently visited and saw everything from the insane ornamentation in the lobby to the former smoking lounge that recently caught the eye of Woody Allen. We also chatted with UPCA’s executive director Mike Fitelson about why this space is truly one-of-a-kind.

After just 13 months of construction, Loew’s 175th Street Theatre opened on February 22, 1930, the last of the five Wonder Theatres. It was preceded by the Loew’s Jersey, which opened on September 28, 1929. Also opened in 1929 were the Loew’s Paradise in the Bronx, the Loew’s Kings in Brooklyn, and the Loew’s Valencia in Queens. Both the Loew’s Jersey and the Loew’s Kings operate as cultural/performance spaces today, while the Bronx and Queens locations are religious spaces. As we previously explained, the theaters were “built by the Loew’s Corporation not only to establish their stature in the film world but to be an escape for people from all walks of life. This held true during the Great Depression and World War II.”

The chandeliers crank down for cleanings and to have their roughly 70 bulbs replaced

The chandeliers crank down for cleanings and to have their roughly 70 bulbs replaced

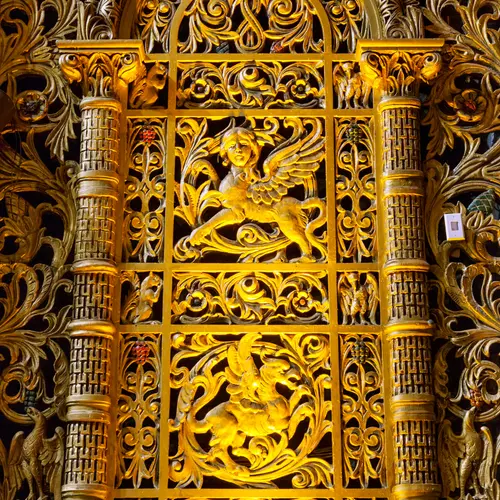

Though the exterior has a rather hard, Mayan-inspired look, the interior architecture at the Loew’s 175th is perhaps the most diverse of all five theaters. It was designed by Scottish-born, NYC-based architect Thomas W. Lamb, who had already established himself as one of the leading architects of the movie theater boom of the 1910s and ’20s. He’s also responsible for the Cort Theatre, the former Ziegfeld Theatre, and the former Capitol Theatre. Decorative specialist Harold Rambausch, of Waldorf Astoria and Radio City fame, helped to style the interiors.

For years, architecture critics have struggled to define the theater’s style. The most accepted characterization is “Cambodian neo-Classical,” but David W. Dunlap described it in the Times as “Byzantine-Romanesque-Indo-Hindu-Sino-Moorish-Persian-Eclectic-Rococo-Deco,” whereas times reporter Nathaniel Adams summed it up as a “kitchen-sink masterpiece.” In Lamb’s own words: “Exotic ornaments, colors and scenes are particularly effective in creating an atmosphere in which the mind is free to frolic and becomes receptive to entertainment.”

And Fitelson shared his own ideas with us: “This was the fifth Wonder Theatre to be designed. [The others] had very specific styles, but at the end of the day, they had all these ideas they couldn’t squeeze in the others. So at the end of the day, they said, ‘everything that’s left on the cutting-room floor we’re going to stick in the Palace.'”

The columns are actually mail-ordered. The Loew’s Corporation was putting up so many theatres across the country at this time, that they’d buy them in bulk.

The columns are actually mail-ordered. The Loew’s Corporation was putting up so many theatres across the country at this time, that they’d buy them in bulk.

Around the time the theater was built, Americans grew fascinated with travel to the “Orient” and “Far East.” This explains why Dunlap wrote that Lamb borrowed styles from “the Alhambra in Spain, the Kailasa rock-cut shrine in India, and the Wat Phra Keo temple in Thailand, adding Buddhas, bodhisattvas, elephants, and honeycomb stonework in an Islamic pattern known as muqarnas.”

Throughout the lavish interior are ornate chandeliers, filigreed walls and ceilings, and hand-carved Moorish patterns. Among the eclectic ornamentation are Buddhas, lions, elephants, and seahorses. You’ll also see many authentic Louis XV and XVI furnishings brought in by Reverend Ike.

When the theatre opened, it presented films and live vaudeville acts. Opening night saw the films “Their Own Desire” and “Pearls” and a live musical stage performance by vaudevillians Al Shaw and Sam Lee.

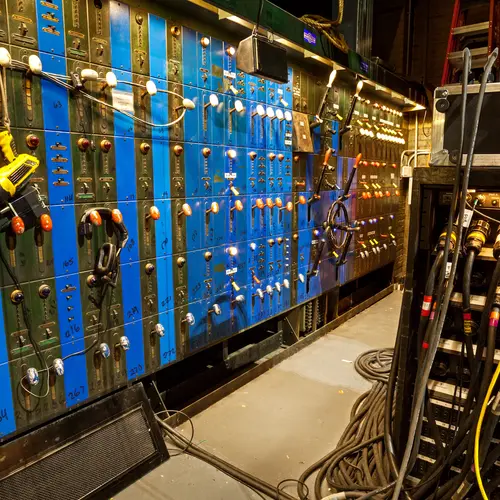

All of the Wonder Theatres had identical Robert Morton “Wonder Morton” pipe organs with a four-manual console and 23 ranks of pipes. The Robert Morton Organ Company of Van Nuys, California was the second largest producer of theatre organs behind Wurlitzer, and they were known to be “tonally powerful while retaining a refined, symphonic sound.” The Palace’s organ is the only one to remain unaltered in its original home. It was rediscovered in 1970 after sitting disused for nearly 25 years under the stage, which had been sealed by the previous owners. It was then used by the church but suffered water damage in later years. Beginning in 2016, the New York Theater Organ Society and UPCA began a full renovation of the organ, working to raise $1 million over five years to bring back the “only remaining, consistently used theatre organ” in the city.

Pictured above is the “men’s smoking lounge.” Since women weren’t supposed to be smoking, their smoking lounge, referred to as a “retiring lounge” was a much smaller, discrete space.

Fitelson says the best secret of the theater is that the Reverend turned the men’s smoking lounge into his library, adding floor-to-ceiling bookshelves. When he passed away in 2009 and all his books were put in storage, they painted the walls the current red. Since the photos from the ’30s are all black-and-white, there’s no way of telling if it was the original color. They also painted the fireplace stark white. When Woody Allen came in in 2015 to shoot “Cafe Society,” his team wanted to use the room as a 1920s jazz lounge and said they’d like to paint the fireplace but would restore it after filming. But Palace leadership thought the new paint job was so spectacular, they decided to keep it!

By the mid-’60s, middle-class families had begun relocating to the suburbs where they were taken by the new “mega-plex” phenomenon. The Loew’s 175th Street closed in 1969 after a final showing of “2001: A Space Odyssey.” Shortly thereafter, Reverend Frederick J. Eikerenkoetter II’s church purchased the building for $600,000 in cash and renamed it the Palace Cathedral, though it quickly became known as “Reverend Ike’s Prayer Tower.” His Sunday services would draw 5,000 people into the then-3,000-seat auditorium.

The only permanent change Rev. Ike made to the building was to add a “Miracle Star of Faith” to the cupola on the building’s northeast corner. It can be seen all the way from New Jersey and the George Washington Bridge. He also undertook an extensive renovation of both the facade and the interior, bringing in artisans from Italy and Eastern Europe to tackle the job.

In the early 2000s, the theatre began renting its space out to musicians from Bob Dylan and Neil Young to Adele and Bon Iver, along with film shoots for Blacklist, Law & Order, and even Beyonce’s Target commercial.

UPCA became an official nonprofit in 2014, founded by Reverend Ike’s son, musician Xavier Eikerenkotter. Its mission is to serve Northern Manhattan artists, youth, and audiences through artistic programming at the United Palace. Over the years UPCA has helped return Movies to the Palace, brought dance (Danza!) programming uptown, invited local artists to perform in the Lobby Series, and provided Community Arts Programs through partner organizations.

In addition, the United Palace spiritual center continues to offer Sunday services. as well as new programming such as Open Heart Conversations–a guided space to meet, talk and explore the world’s varied and rich spiritual traditions– for everyone from devout followers to agnostics. As an inclusive spiritual community, the United Palace seeks to cultivate compassion, wisdom, and peace through spiritual practices, sacred service, and joyous connection through music, arts, and entertainment.

The United Palace venue, which allows the 3,400-seat theatre to be rented for concerts and all kinds of performances and screenings. Though the Eikerenkotter family separated from the venture this past fall, the church still maintains ownership of the building.

Almost exactly a year ago, the city designated the United Palace Theatre an official city landmark. Though this only protects the exterior, but it doesn’t seem as though there’s anything to worry about after all these years.

RELATED:

- Behind the scenes at the Loew’s Jersey City: How a 1929 Wonder Theatre was brought back to life

- Loew’s Kings Theatre Will Reopen in Flatbush With All of its 1920s Gilded Glamour

- Inside the Village East Cinema, one of NY’s last surviving ‘Yiddish Rialto’ theaters

All photos taken by James and Karla Murray exclusively for 6sqft. Photos are not to be reproduced without written permission from 6sqft.