Fallout Shelters: Why some New Yorkers never planned to evacuate after a nuclear disaster

Images: A model fallout shelter, 1955. Image Wiki Commons

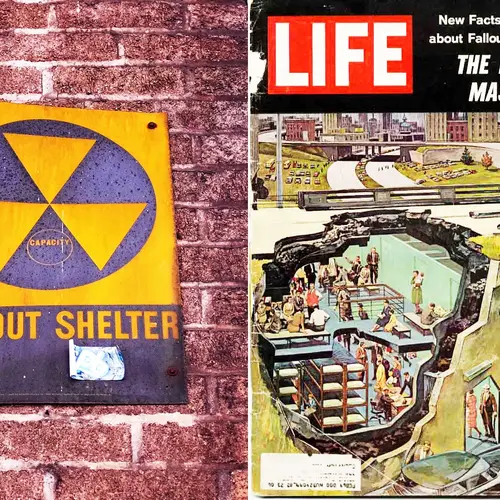

Decades after the end of the Cold War, ominous black-and-yellow fallout shelter signs still mark buildings across New York City’s five boroughs. The actual number of designated fallout shelters in the city is difficult to discern. What is known is that by 1963, an estimated 18,000 shelters had been designated, and the Department of Defense had plans to add another 34,000 shelters citywide.

While the presence of a fallout shelter in one’s building may have given some residents peace of mind in an era when nuclear destruction seemed imminent, in reality, most of New York’s fallout shelters were little more than basements marked by an official government sign.

A small percentage of shelters were fortified underground bunkers stocked with emergency supplies, but these were rare and primarily built for high-ranking government officials. The majority of shelters, including nearly all those that were visibly marked, were known as “community shelters,” and by all accounts, they offered little special protection. Inspector guidelines simply indicated that “community shelters” should be kept free of trash and debris and have a ventilation system that can provide a “safe and tolerable environment for a specified shelter occupancy time.” Regulations for the ventilation systems appeared to be open to interpretation, leaving individual inspectors to determine which of the city’s windowless basements would ultimately make the cut.

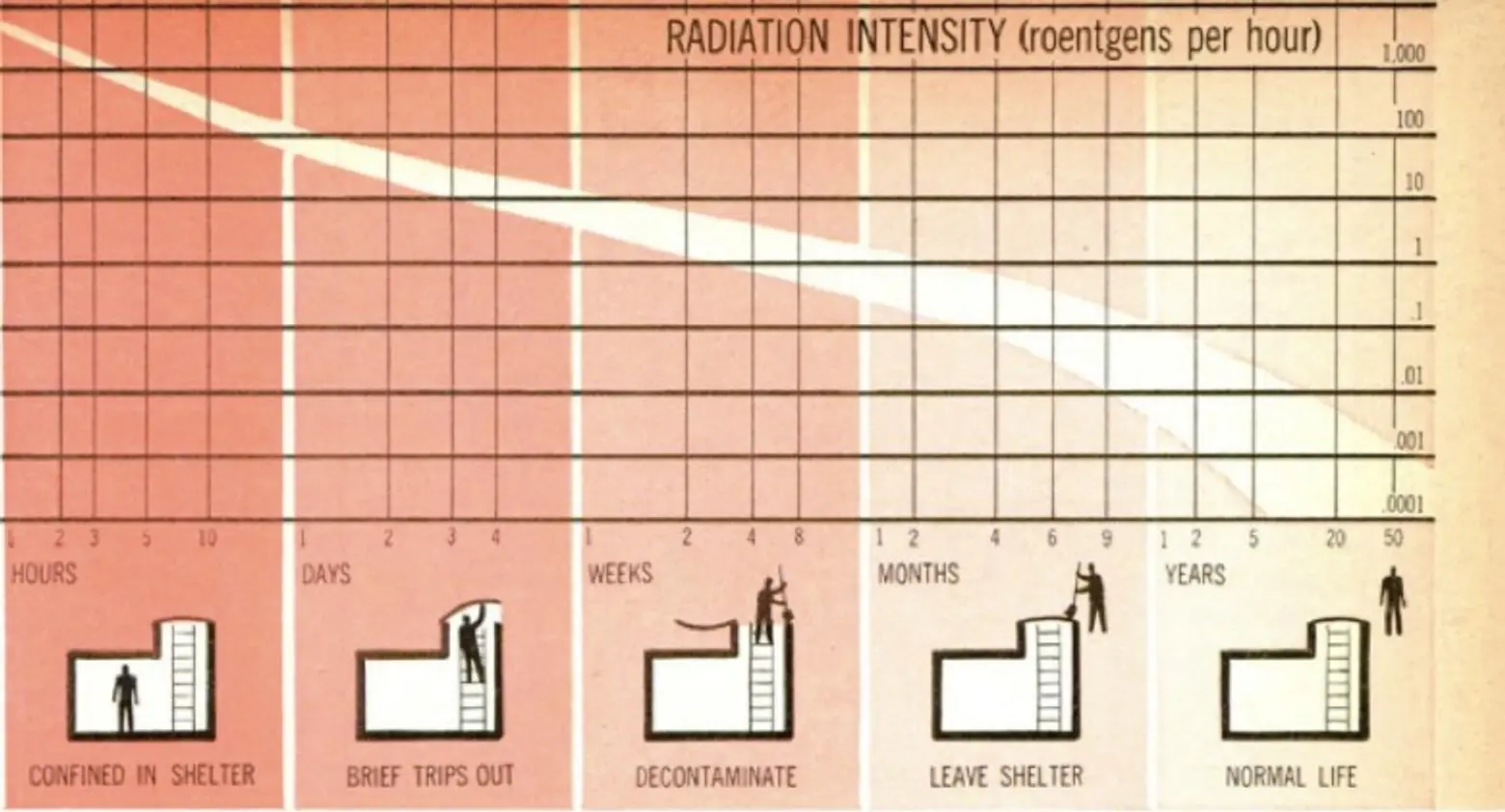

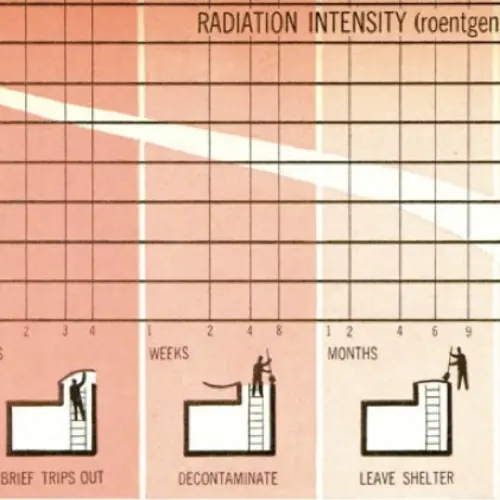

A December 1961 article in Popular Mechanics featured the above chart to help people determine when it might be safe to leave their fallout shelter and how long it would take to return to “normal life.”

A December 1961 article in Popular Mechanics featured the above chart to help people determine when it might be safe to leave their fallout shelter and how long it would take to return to “normal life.”

What is now now clear is that had New York experienced a nuclear attack, most fallout shelters would have done little or nothing to protect residents from fallout. There is also evidence, however, that some New Yorkers had no intention of evacuating to a local shelter either way. In fact, at the time, many city residents appeared as concerned about the negative side effects of fallout shelter living as they were about radiation.

A still from the 1964 government produced film, Public Shelter Living: The Story of Shelter 104, which dramatized fallout shelter living.

A still from the 1964 government produced film, Public Shelter Living: The Story of Shelter 104, which dramatized fallout shelter living.

The Social and Psychological Side Effects of Fallout Shelter Life

In the 1960s, many New Yorkers firmly believed that being trapped inside a windowless basement for days and even weeks with their neighbors may be potentially more harmful than being showered with nuclear fallout. That’s right—for many, toxic neighbors were considered an even greater threat than toxic fallout.

To be fair, New Yorkers were not alone in fearing the idea of being trapped in a windowless basement with their neighbors for days and weeks on end. By the late 1960s, the Office of Civil Defense was studying the potential social problems raised by fallout shelters, and in some cases, carrying out fallout shelter simulations. In one study, carried out in Athens, Georgia, 63 of the study’s 750 participants left within the first 15 hours. In the end, most studies had similar results with a relatively high percentage of participants fleeing shelters only hours into the simulations.

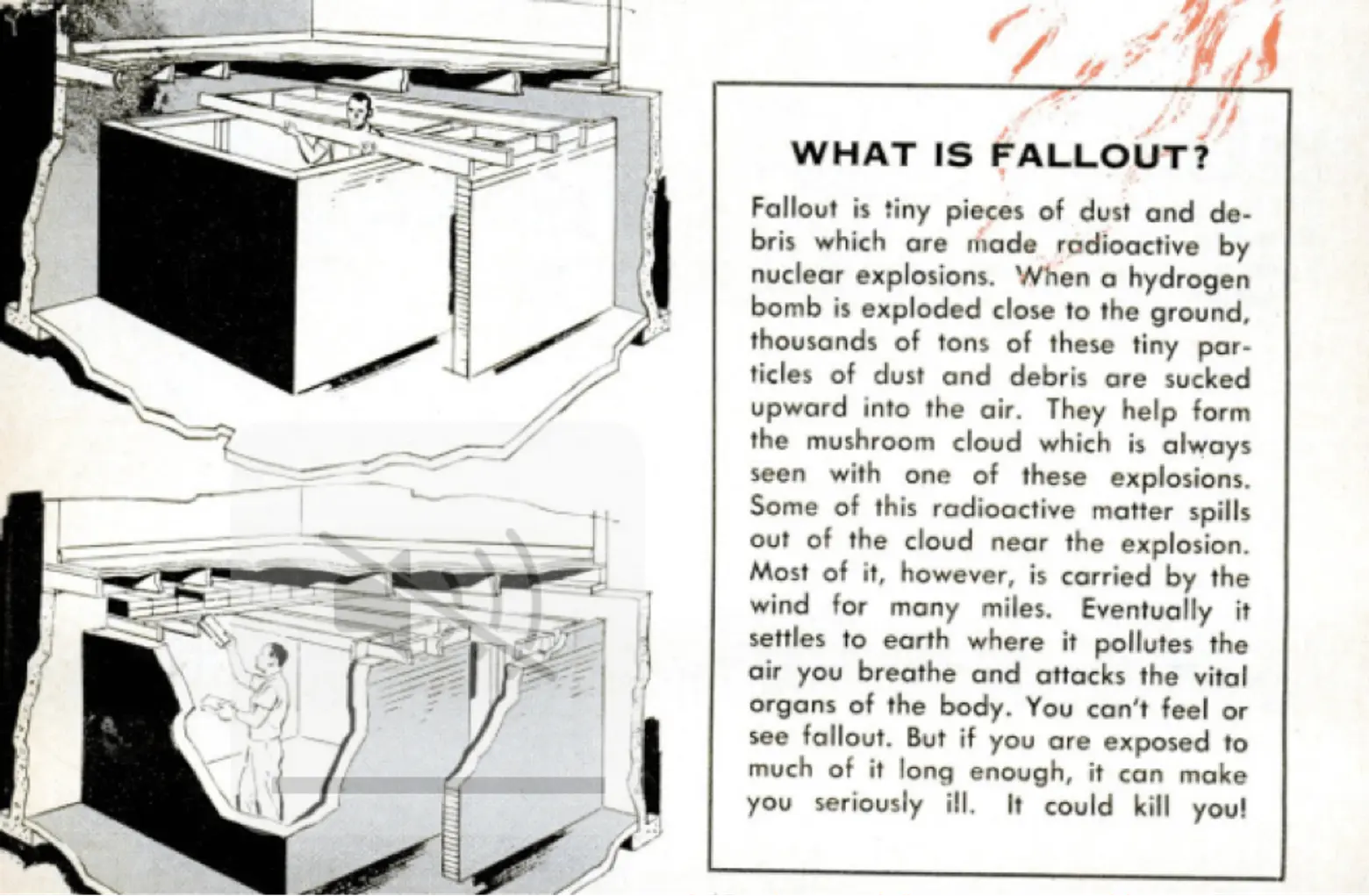

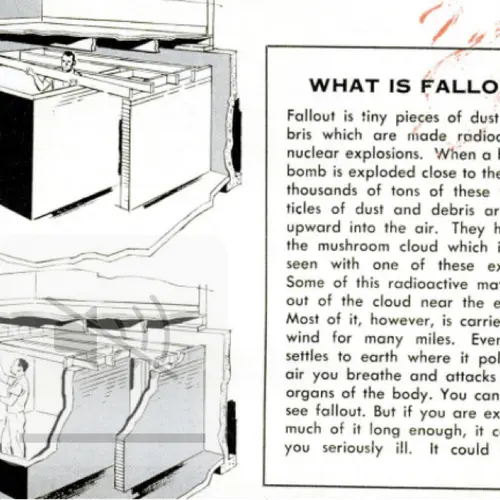

An October 1960 feature in Popular Mechanics provided educational advice on fallout and how to avoid it.

An October 1960 feature in Popular Mechanics provided educational advice on fallout and how to avoid it.

Nevertheless, the Office of Civil Defense attempted to put a positive spin on the results, noting that participants who were able to stick it out often emerged feeling stronger and more prepared for the event of an actual nuclear attack. They also asserted that with the right precautions, the recognized psychological effects of living in a fallout shelter, which include severe depression, can be mitigated.

A 1963 study by the Office of Civil Defense recognized that “each person will be a victim of severe stresses to his need system so that a new, overall need may emerge, to get out, away from the multiple stresses.” But this need, which the study suggests may be as strong as the desire for group acceptance, a Cadillac, or smoking, can be controlled by ensuring the shelter is a hopeful, calm, and most importantly, well managed environment. Acknowledging that “poor management will result in an inferior adjustment and attitude on the part of shelter occupants,” by the mid 1960s, the Office of Civil Defense had launched a fallout shelter manager training program to ensure that every fallout shelter would also have a live-in superintendent.

Unfortunately, in New York, going crazy or suffering from severe depression in the close company of one’s neighbors wasn’t the only problem residents feared facing if forced to take refuge underground.

Idealized American fallout shelter, around 1957. Image via Wiki Commons

Idealized American fallout shelter, around 1957. Image via Wiki Commons

The Quality of New York City’s Fallout Shelters

While designated shelters in some neighborhoods were pristine and equipped with emergency supplies, in other areas of the city, they were considered too hazardous to enter. One 1963 article in the New York Times profiled a fallout shelter running under three tenements on East 131 Street in Harlem. Reports indicated that the shelters were full of leaking raw sewage, garbage, and rats. “Who’d want to go down there?” one local resident told a reporter. “If fallout came, I’d just run.” Asked about the designated shelter, another woman in the neighborhood said that in it, “rats are as big as dogs and run through the house like horses.”

With typical New York City resolve, officials noted that if people were already living in the tenements above, they could certainly survive in the basement for a week to 10 days in the face of radioactive fallout. After all, survival not luxury was the objective. According to the article, however, most local East Harlem residents had already concluded that exposure to radioactive fallout would potentially pose fewer risks.

Fallout Shelters Today

By the late 1970s, many New Yorkers were more concerned about the rotting food in the city’s fallout shelters than they were with a pending nuclear threat and with good reason. In the 1960s, an estimated $30 million worth of food had been stashed away in basements across the New York City area. Two decades later this food had started to attract roaches, rats, and sometimes, vandals. For this reason, long before the Cold War was officially over, many residential fallout shelters were already being cleaned out and reclaimed as storage spaces or converted into more other types of common spaces from laundry rooms to fitness rooms.

Whatever the purpose, these windowless basement common spaces are still not a favorite of most tenants, but if you happen to have one in your building, it is worth noting that while the average load of laundry takes only 40 minutes, the average stay in a community fallout shelter was expected to last at least 10 days, and in some cases, much longer.

RELATED:

Explore NYC Virtually

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

1960s fallout shelters were inadequate to protect occupants from the initial bomb radiation and often inadequate to protect people from the bomb pressure. Old civil defense shelters did not work. Certainly the Department of Defense’s “Family Shelters” were almost completely inadequate protection. We have written about the old designs, as well as the propaganda surrounding how nuclear war would play out, another concept twisted for political reasons. Modern nuclear shelters are based on engineering principles rather than protection factor guesses. See: “Old Civil Defense Shelters Don’t Work to Protect from Nuclear War, but Modern Rated Underground Shelters Do,” https://noradshelters.com/old-civil-defense-shelters/

New Yorkers, along with most big city people, would die off in the event of a nuclear attack. Big cities would be targeted first since destroying them causes the most damage in terms of population loss. A shelter won’t help you if you are a primary target. Even if you tried to leave, the roads, bridges, and tunnels would be choked with cars. At first they would be cars full of people also trying to leave but later, after the bomb, they would be full of corpses or abandoned and forget about trying to move them because their electrical systems would be fried and their tires would be melted off so if you were still somehow alive in a big city after a bomb blast, you would basically be trapped there. Since the roads were blocked, no supplies would be able to get in and I wouldn’t count on the government airlifting supplies into a city where they may be few or no people when there are still millions of known survivors outside the cities in need. No food, no medicine, no warm clothing to protect you from exposure if it were winter. You’d have to live on what you could scrounge but since everything would be irradiated, every bite of food and drink of water would bring you one swallow closer to death. It would be the people well outside the cities in “fly-over country” that would fare the best because they would have less radiation to contend with and would still be able to raise food and find clean water. How many city folk do you think know how to drill a well or plow a field? They would also have plenty of guns and ammo to fight off anyone who tried to flee the cities and put a strain on their limited resources. Most of the military would also be gone since many military installations are located near big cities and would be within the fallout radius, if not the blast radius, of a nuclear weapon so who do you depend on to protect your life from other people who would be willing to kill you for a moldy candy bar after the bombs fall?