Field Trip to the American Dream (Via the Bronx)

My English composition class at a CUNY school resembles a Benetton ad minus the posing and singular fashion aesthetic. I could run the numbers, but I don’t need to make like Nate Silver to prove my class is almost entirely of immigrants or first generation Americans from a wide range of backgrounds. This makes things particularly interesting when we study the ‘American Dream’, for it’s far more relevant to my students than it is to, say, me — all snug and secure in my status as a second-generation American not living with the hope for citizenship nor the fear of deportation of myself or my loved ones.

One of the materials I use when teaching the American Dream is an article from September of 2013 in The Times about Marco Saavedra, a young man brought here illegally as a toddler in the early ‘90s by his Mexican parents who own and operate a restaurant in the Mott Haven section of the Bronx. Under the auspices of his parents’ emphasis on education, Marco was able to thrive in the public schools’ of NYC and secure full scholarships to Deerfield Academy and then Kenyon College, from where he graduated in 2011. Impressive.

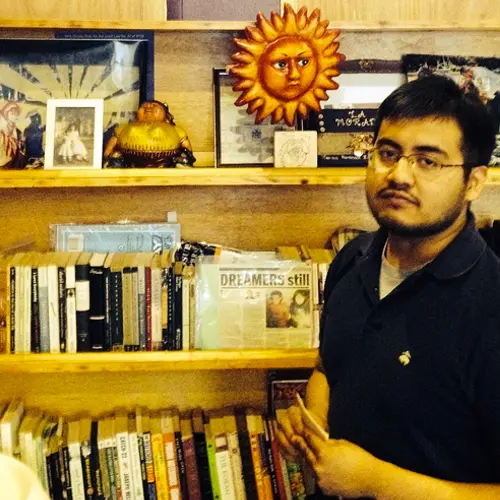

Image by Voices of NY

Upon graduation, though, Marco felt conflicted. His pesky head full of ideas and information left him questioning his responsibility to not just his immediate community but those all over our nation living in perpetual unease about their status as citizens. Marco chose to become an activist, aligning himself with the National Immigrant Youth Alliance, a nationally recognized organization advocating for the passage of The DREAM Act. Last August, Marco became one of the original “Dreamers” — a group of nine young immigrants who were intentionally detained crossing the border from Mexico to Arizona in an effort to bring attention to the cause. Marco was granted asylum. His status is pending, and a second trip back to his unfamiliar homeland of Mexico, a permanent one, may be in his future.

His parents were, ah, well, yeah: pissed. They didn’t come to America to have their son instigate his own return to Mexico! The publicity put the whole family at risk, as well. Eventually, though, Marco’s parents were able to accept and understand their son’s decision as they waited for word on his (and their) status. End of article.

So, what of said status? My students wanted to know. I wanted to know. So, we called La Morada, the restaurant owned by Marco’s parents. A Spanish speaking student translated a conversation with Marco’s mom, Natalia Mendez. We learned that Marco’s status is still pending. We also learned that the specialty of La Morada is a white mole sauce and that Marco works there as a waiter. I called FIELD TRIP!!!

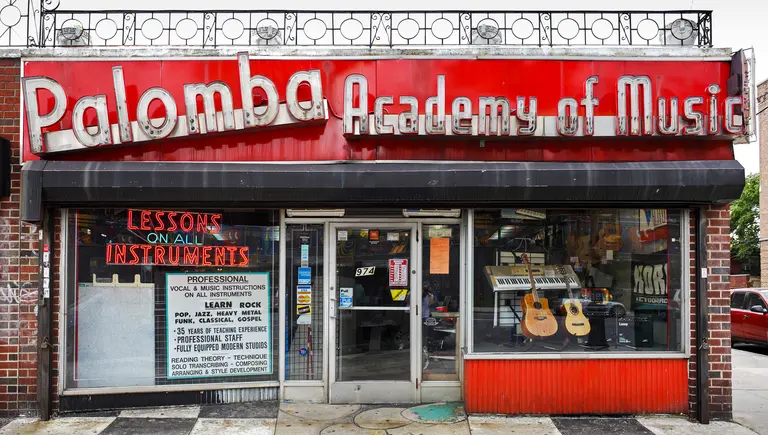

So, one recent afternoon, my class and I ditched the classroom and traveled by train from downtown Brooklyn to Willis Avenue in the Bronx. La Morada is found under a purple awning of a single storefront in the middle of a low-slung commercial block, among the familiar establishments of such urban stretches: cash checking, bodegas, legal services, hair salons, $.99 stores, churches, fast food, cell phones.

The inside of La Morada is notable for the bookshelves that serve as a partition in back and colorful canvases that decorate the walls, original efforts by the owners son, Marco Saavedra, a bespectacled young man whose whiskers can’t belie his boyish countenance, who greets us as we enter and shows us to our our classroom for the day: a chain of four-tops that take up half of the restaurant’s seating capacity. We are introduced to Marco’s parents and one of his two sisters, who take our orders and begin to prepare our suppers.

After the plates are cleared, we engage Marco in a long conversation about his situation. He speaks quickly and with confidence, offering long responses informed by the syntax and verbiage of an educated and passionate young man. His mother watches from the nearby counter, her face a mixed-message of pride and concern, her hands clasped just below her heart.

From Marco, we learn about being raised in constant fear of deportation, of having families torn apart; we learn about what it’s like to grow up in the Bronx and attend school in leafy Massachusetts and rural Ohio; we learn of the decision-making process of becoming an activist and the risks involved; we learn about the conditions on the Mexican border and the corporate-owned detention center where detainees are held; we learn of the roughly 2 million people deported by the Obama administration and the estimated 12 million illegal immigrants in the United States awaiting legislation that allows for a path to citizenship; we learn that the DREAM Act with its myriad of benefits for young illegals can stall even in progressive states like New York. We learn what its like to live in a family where one member has put all of their status at risk.

In the end, I believe, we have learned that the American Dream is real and imperfect and best represented, often, by the courage of those who are not officially Americans.

Lead image of Marco by Kenyon College

Andrew Cotto is the author of The Domino Effect and Outerborough Blues: A Brooklyn Mystery. He has written for numerous publications, including The New York Times, The Huffington Post, Men’s Journal, Salon.com, the Good Men Project, and Teachers & Writers magazine. He has an MFA in Creative Writing from The New School. He lives in Brooklyn, New York. Follow him on Twitter @andrewcotto