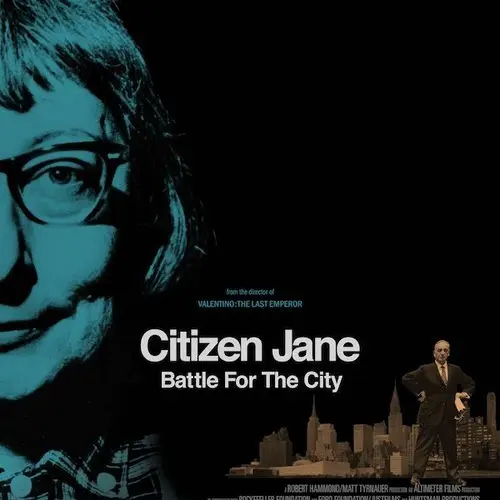

New Jane Jacobs documentary spotlights her achievements in NYC and lessons to be carried forward

One of the most iconic battles to decide the fate of New York City was waged, in the 1950s and ’60s, by Jane Jacobs and Robert Moses. He, a Parks Commissioner turned power broker, was known for his aggressive urban renewal projects, tearing tenements down to build higher, denser housing. She, often dismissed as a housewife, emerged as his most vocal critic—not to mention a skilled organizer with the ability to stop some of Moses’ most ambitious plans.

A new documentary, Citizen Jane: Battle for the City, takes a close look at the groundbreaking work of Jane Jacobs and its importance in our urbanizing world today. Matt Tyrnauer, the director behind Valentino: The Last Emperor, compiled footage of both Jacobs and Moses alongside 1950s and ’60s New York, which is paired with voiceovers of Marissa Tomei and Vincent D’Onofrio as the battling duo. Experts in urban planning—everyone from Paul Goldberger to Robert A.M. Stern—also discuss Jacobs’ massive influence on housing policy and urban planning, as the film makes a convincing argument that Jacobs’ planning philosophies are needed now more than ever.

A behind-the-scenes shot in China of director Matt Tyrnauer. Photo by Altimeter Films and courtesy of IFC Films

A behind-the-scenes shot in China of director Matt Tyrnauer. Photo by Altimeter Films and courtesy of IFC Films

The film’s opening takes a look outside New York, with one expert pointing out that “cities have been expanding, and urbanization has been expanding around the globe at an exponential fashion.” While much of New York’s housing stock already exists, the development of cities in places like China and India is unprecedented, causing lightning-fast construction of new towers and highways. Such rapid urbanization brings up powerful questions: “Who decides what the physical form [of the city] will be?” the film asks. “How the city is going to function, and who is going to live in the city?”

The documentary argues that many of these questions can be traced to the “two great figures who in the middle of the 20th century embodied the struggle for the city”—Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs. Moses came to represent the ideals of modernist planning, of demolishing old slums and making way for shiny new towers. Jacobs introduced the city to a philosophy of “planning about people”—city planning that deferred to the people who lived there and also sought to enhance—not destroy—connections between residents and local businesses, neighbors, even strangers on the street. The film isn’t incorrect to call this “a war between opposing forces.”

Photo of Robert Moses and Mayor Wagner from the film. Photo by Walter Albertin, courtesy of IFC Films.

Photo of Robert Moses and Mayor Wagner from the film. Photo by Walter Albertin, courtesy of IFC Films.

The documentary begins in the 1930s, post-Great Depression, as Moses is making his transition from a Parks Commissioner developing parks and beaches across the city into the “master builder” that cemented his legacy. With an increasing number of slums and inadequate housing in New York, his idea was to “wipe the slate clean,” as Paul Goldberger puts it. On the other end, Jacobs is beginning her career as a freelance journalist, writing about city neighborhoods for Vogue.

The pair doesn’t clash until the early 1950s, in post-war New York, with the idea of a “modern, expressway tower city” taking hold. Jacobs was then on staff at Architectural Forum writing increasingly about urban blight. Such coverage led her to Philadelphia and East Harlem, where Jacobs was shocked to find new development there that seemingly ended the community life on the street. This initial inquiry into the planning policies of the 1950s would lead to “a new theory of how cities function,” Max Page, professor of architecture and history, says in the film.

The documentary displays plenty of historic New York footage to enhance the story. The visuals of mass housing projects going up—inspired by the modern planning ideas of Le Corbusier—look striking against shots of well-populated, low-density blocks where residents sit on stoops and gaze out windows. Images of desolate sidewalks and green spaces inside the new, hulking complexes make a visual argument that compliments Jacobs.

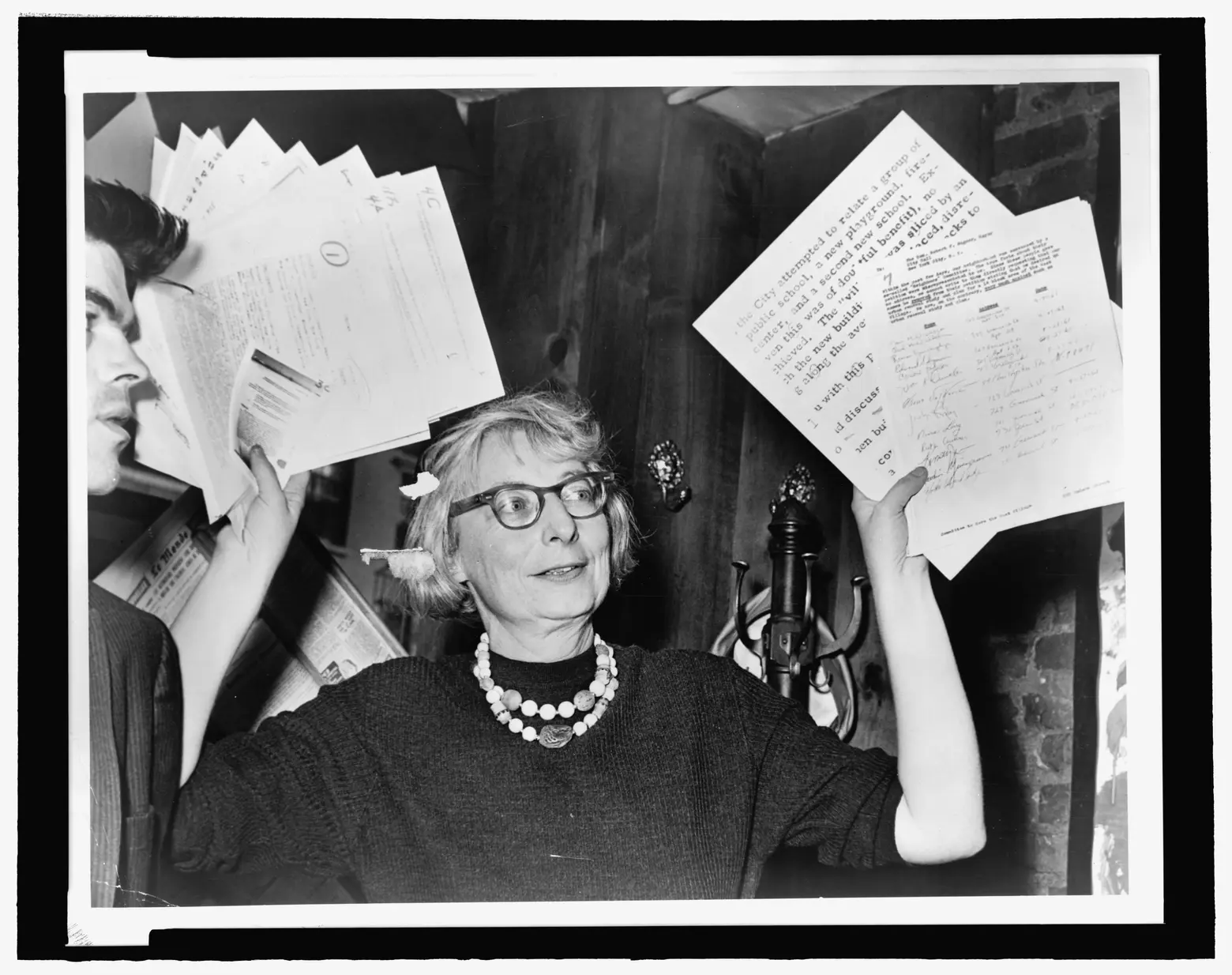

The film also shows how Jacobs, despite her preference to writing, emerged as “a brilliant strategist when it comes to civic action,” as the film puts it. In the late 1950s, she organized residents of Greenwich Village, where she lived with her family, to oppose a proposal by Moses to build a highway through Washington Square Park. It was Moses’ first public defeat and Jacobs’ first taste of victory. From here on out, as Jacobs says in an interview included in the documentary, “I began to devote myself to frustrating city planners.” It was happening at a time, the film points out, in which women were hardly welcomed into the field of city planning. But that didn’t deter Jacobs. As she said in a filmed interview, “It’s wicked to be the victim… you can organize.”

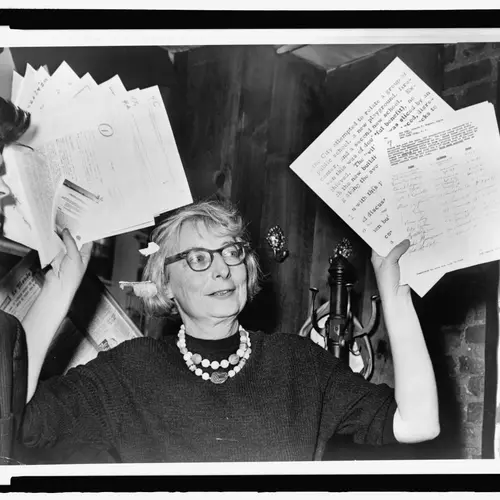

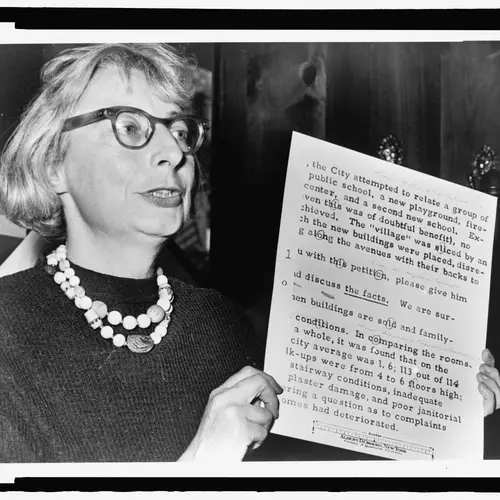

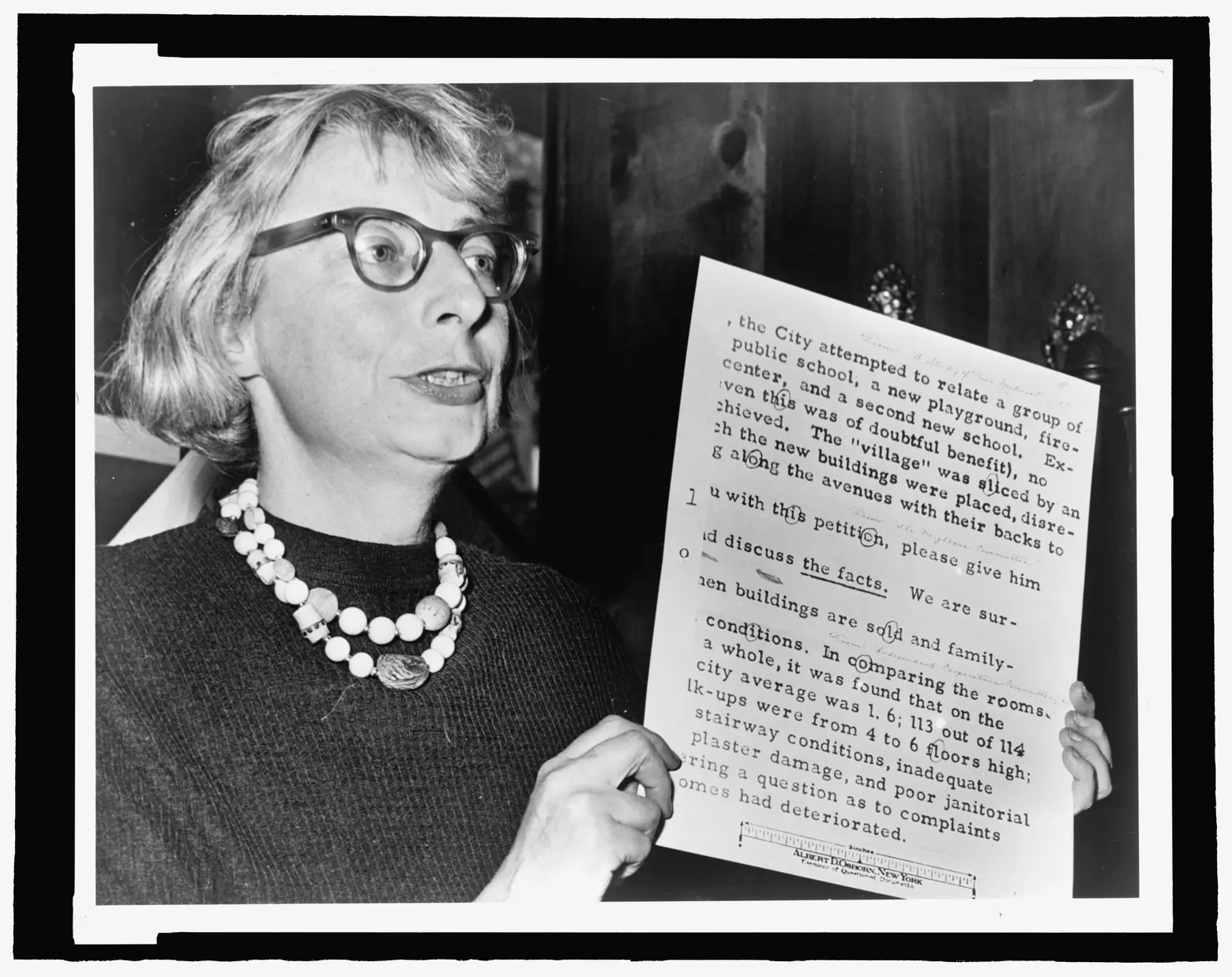

Photo of Jane Jacobs from the film, courtesy of IFC Films

Photo of Jane Jacobs from the film, courtesy of IFC Films

The release of her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities in 1961 would change the profession of city planning altogether. One highlight of the film is Vincent D’Onofrio’s voiceover of Moses, reading his curt dismissal of Jacobs’ work. (Moses’ writing and memos would become increasingly angry, and downright mean, to anyone that opposed him.) But the real pleasure is hearing Marissa Tomei read sections of Jacobs’ book, which introduced readers to now-famous terms like “eyes on the street,” “social capital,” and the “miraculous order” of cities. Her writing on the constant connections forged in the “great network” of a city still resonates. As Paul Goldberg said, “She was explaining how life worked.” As he noted later, “She knew the city is not just a physical object, it is a living thing.”

After the release of Death and Life, Jacobs won other battles chronicled in the documentary: the removal of a slum designation assigned to the West Village, the halting of an expressway proposed to cut through Lower Manhattan. In a particularly engrossing scene, Jacobs narrates a hearing she attended for the proposed LoMax Expressway. The public started growing angry during the hearing and Jacobs was arrested and charged with three felonies. After that, “she becomes a hero,” her friend Francis Golden recalled.

The documentary certainly portrays Jacobs as the hero of this David-and-Goliath battle, especially as American cities began the large-scale demolitions of 1950s housing projects like Pruitt Igoe, and Moses was squeezed out of his powerful planning role by Governor Nelson Rockefeller. Moses eventually resigned from planning in 1962, but his ideas of rapid modernization persisted throughout the decade.

“China today is Moses on steroids,” Dutch-American sociologist Saskia Sassen said in the film. “History has outdone him.” Planner Greeta Mehta warned that global development, without the philosophies of Jane Jacobs, could result in “the slums of the future.” The big question today, they argue, is how to apply to lessons of Jane Jacobs, building cities with great public realms, to an urbanizing population of billions.

For answers, you don’t need to go much further than Jacobs herself: “Historically, solutions to city problems have very seldom come from the top,” she’s quoted in the film. “They come from people who understand the problems first hand, because they’re living with them, and have new, ingenious and often very offbeat ideas of how to solve them. The creativity and concern and ideas down there, in city neighborhoods, has to be given a chance. People have to insist on government trying things their way.”

It was the radical idea, Paul Goldberger said, “to be skeptical. To doubt the received wisdom, and to trust our eyes instead.”

Citizen Jane: Battle for the City is now screening in select New York City theaters and on Video On Demand. To see a list of showtimes, go here.

RELATED: