Finding 42: Swing through these 10 NYC sites associated with Jackie Robinson

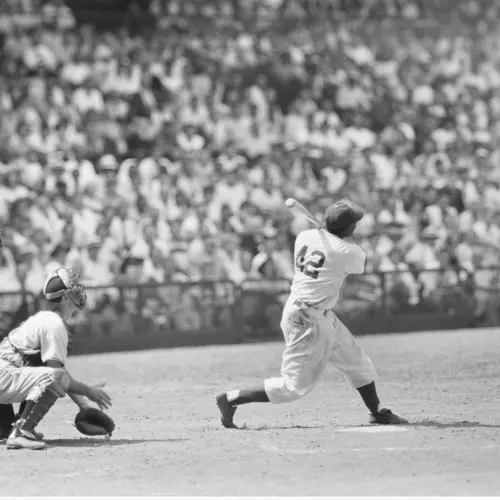

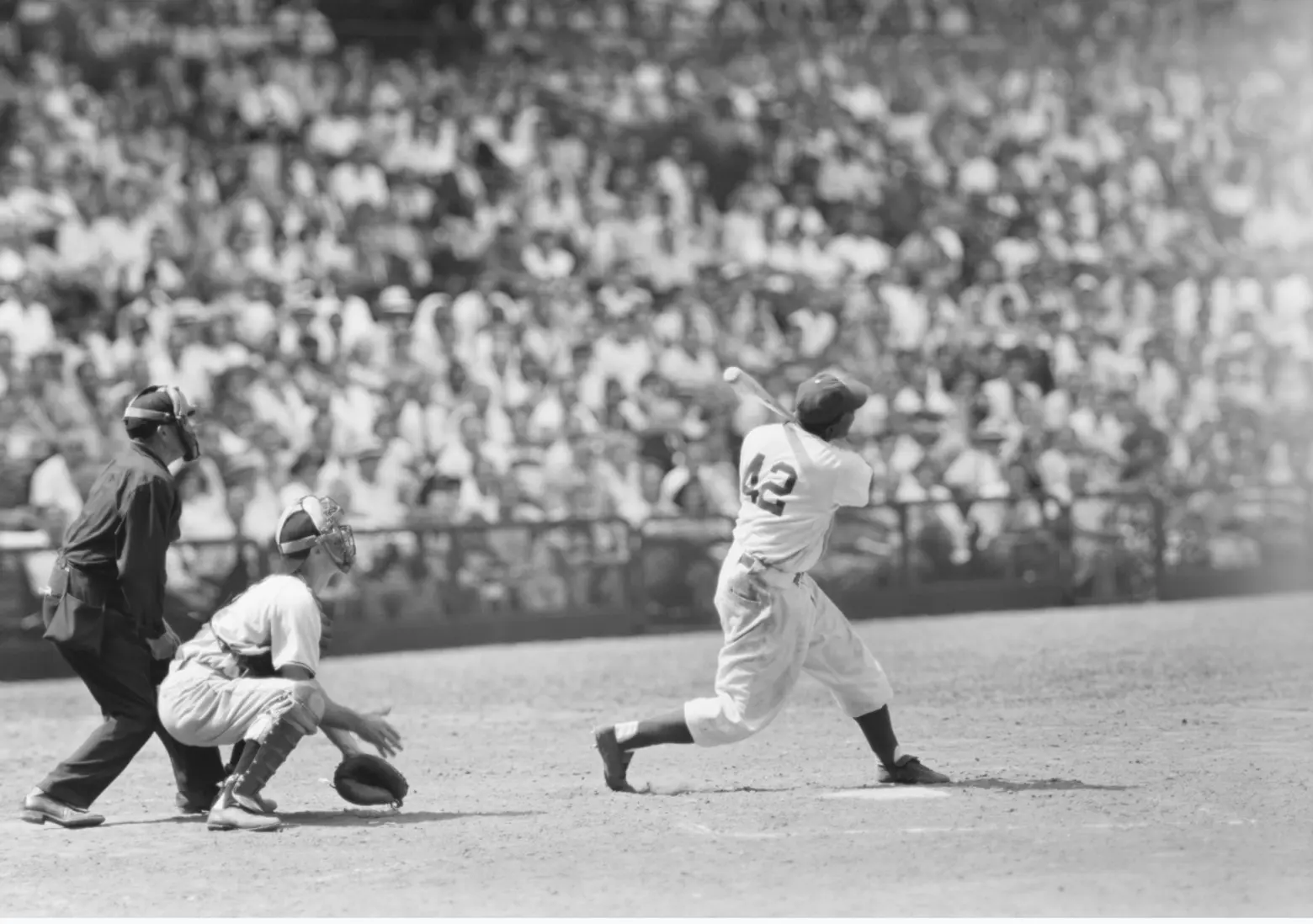

Jackie Robinson at bat, 1949, photo by Frank Bauman, courtesy of MCNY, LOOK Collection

On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson strode onto Ebbets Field, and into history, as the first African American Major League Baseball player. During his stellar 10-year career with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Robinson was the first player ever named Rookie of the Year. He became National League MVP 1949 and was named an All-Star every year from 1949-1954. After retiring from Baseball, Jackie Robinson remained a trailblazer. He became the first African American officer of a national corporation, as well as a Civil Rights leader, corresponding with politicians including Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon, urging each to support true equality for all Americans.

January 31, 2019, would have been Jackie Robinson’s 100th birthday. To mark the centennial, the Museum of the City of New York and the Jackie Robinson Foundation have collaborated on a new photography exhibit “In the Dugout With Jackie Robinson: An Intimate Portrait of a Baseball Legend.” The exhibit features unpublished photos of Robinson, originally shot for Look Magazine, and memorabilia related to Robinson’s career. The exhibit will open at MCNY on the 31st to kick off the Foundation’s yearlong Jackie Robinson Centennial Celebration, which culminates in the opening of the Jackie Robinson Museum in Lower Manhattan in December 2019. As part of the celebration, 6sqft is exploring the history of 10 spots around town where you can walk in the footsteps of an American hero.

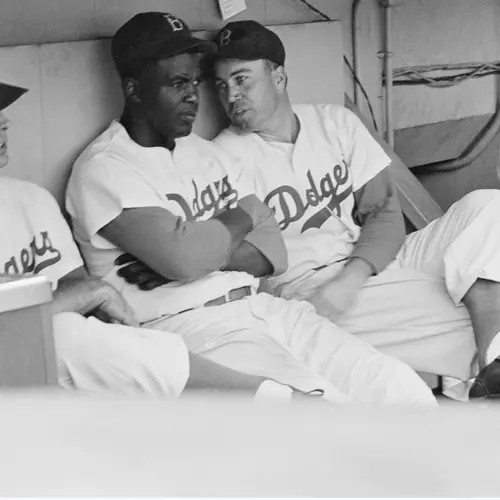

Robinson and teammates in the dugout signing autographs, 1949, Photo by Kenneth Edie, Courtesy of MCNY, LOOK Collection

1. Jackie Robinson Playground

Jackie Robinson Playground, at 46 McKeever Place in Flatbush, sits on the site of Ebbets Field, home of the Brooklyn Dodgers, from 1913-1957, where Robinson made his Major League debut and spent 10 seasons knocking it out of the park. (He maintained a lifetime average of .311). The playground opened to the public in 1969 and was named for Robinson in 1985.

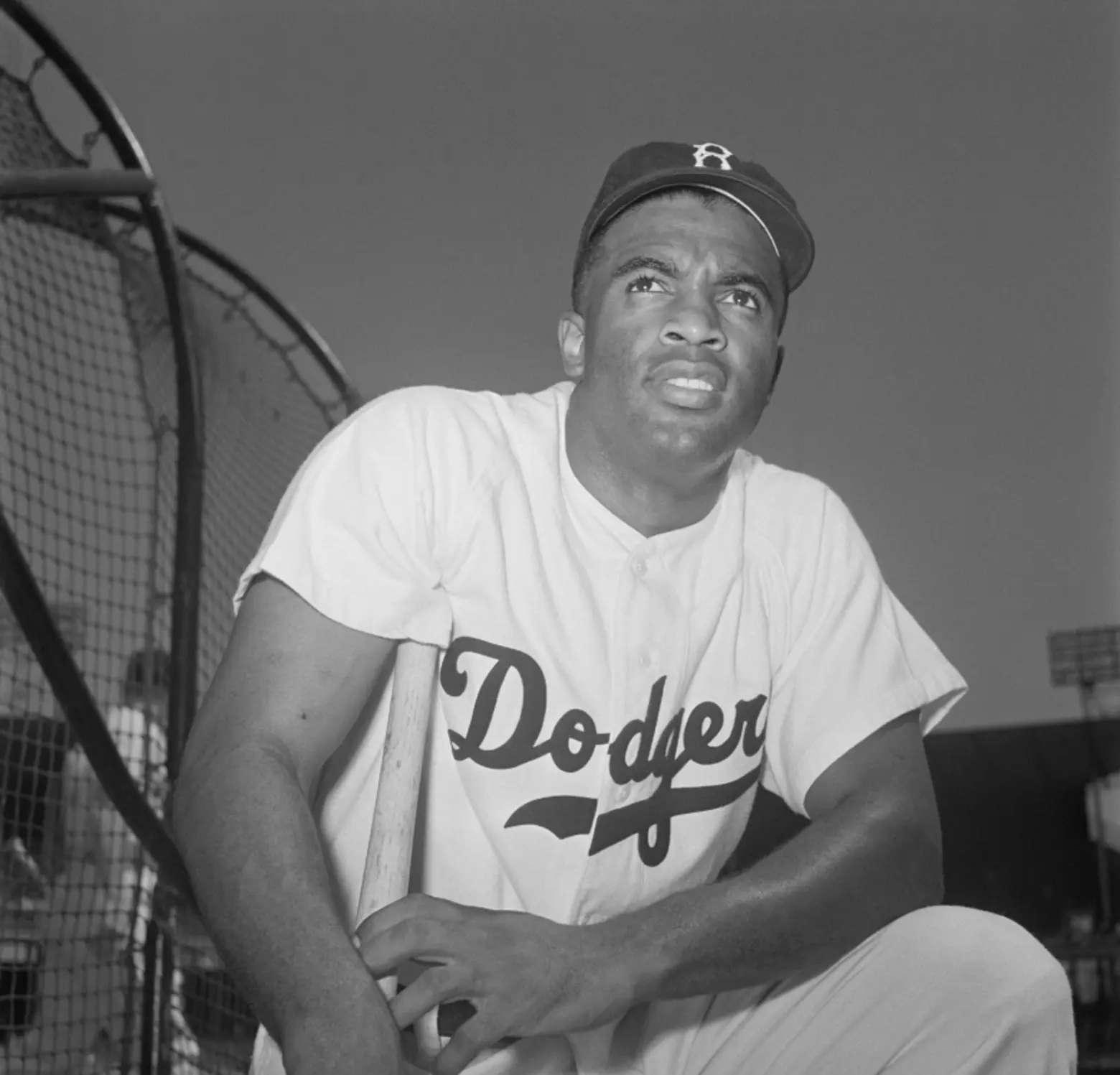

Robinson, 1949, photo by Frank Bauman, Courtesy of MCNY, LOOK Magazine Collection

2. 215 Montague Street

The Dodgers might have swung for the fences in Flatbush, but from 1938-1957 their business office occupied the fourth floor of 215 Montague Street in Brooklyn Heights. There, on August 28th 1945, the team’s President and General Manager, Branch Rickey, signed Robinson.

He was called up initially to the Montreal Royals, the Dodgers’ international farm team, where he played second base during the 1946 season, before starting at first base for the Dodgers the following year. The building at 215 Montague that housed the Dodgers’ office no longer stands, but a plaque honoring the exchange between Robinson and Rickey was affixed to the site in 1998.

Robinson in the Kitchen at 5224 Tilden Avenue washing dishes, August 1949. The caption on the back of the photograph reads “Here’s the Evidence: Like all good husbands at one time and another Jackie Robinson helps with the dishes.” Via the Brooklyn Collection, Brooklyn Public Library

3. 5224 Tilden Avenue

Robinson and his wife Rachel rented the top floor of this two-story home in East Flatbush, near Ebbets Field, between 1947 and 1949. The house was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

In 1949, the Robinson family moved to 112-40 177th Street in the Addisleigh Park section of Queens, and lived there until 1955. During that time, other prominent African Americans, including Count Basie and Herbert Mills, also made their homes in the neighborhood.

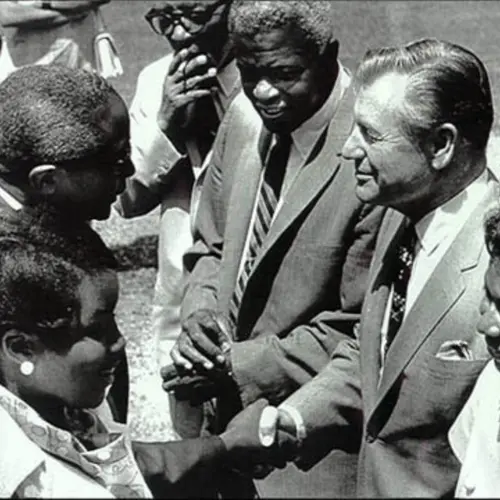

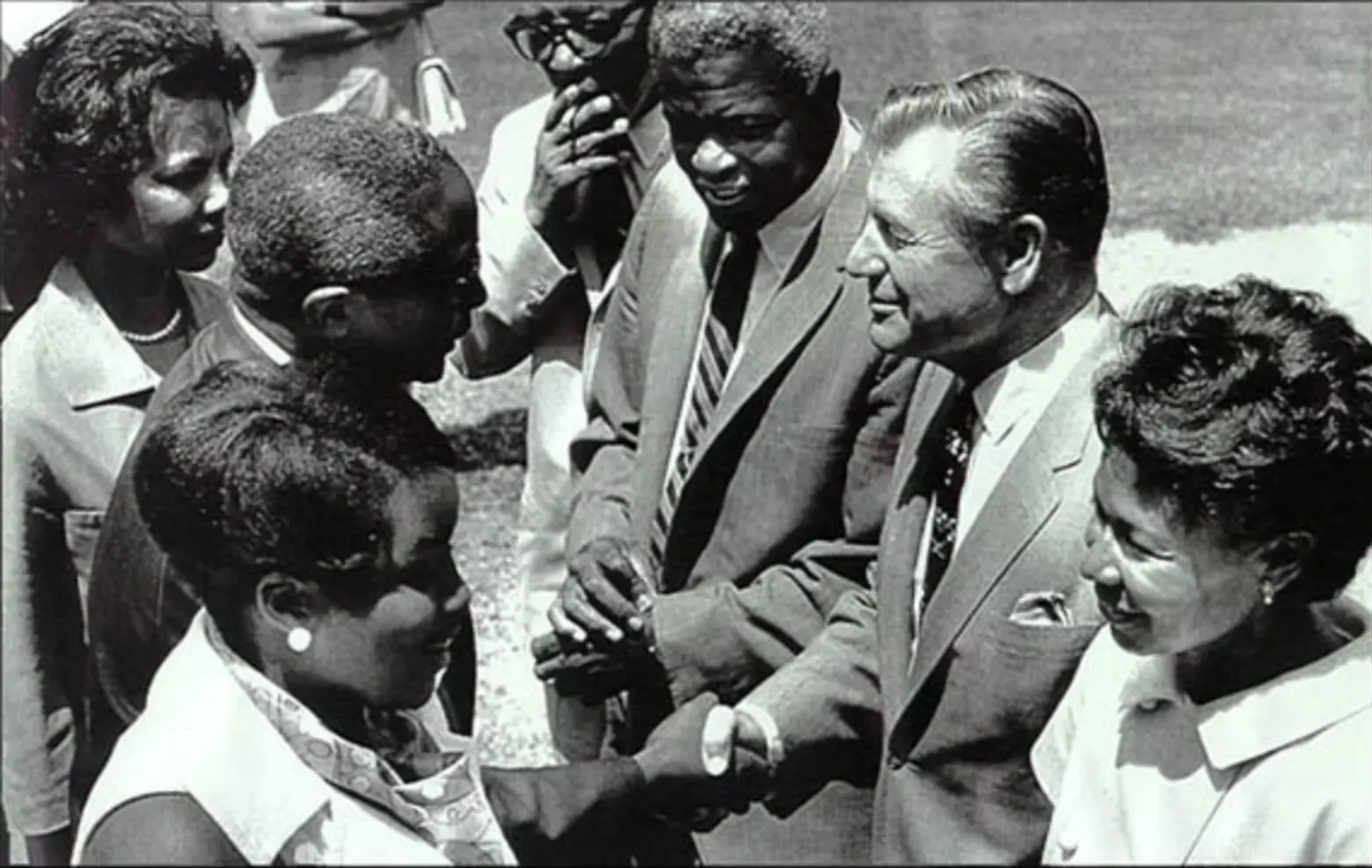

Jackie and Rachel Robinson with Nelson Rockefeller, 1966. Via The Jackie Robinson Educational Archives at UMass Amherst

4. Rockefeller Center

As a national icon, Jackie Robinson’s off-seasons were as busy as his schedule on the field. In January 1953, he agreed to lead NBC’s new non-profit Music Foundation as its Director of Community Activities. The role included on-air appearances, and outreach throughout New York City. Robinson used the post to advocate for Civil Rights within the broadcasting, television and music industries, and within American Culture more broadly.

Robinson’s post at NBC would not be his only association with Rockefeller Center, or the Rockefeller family. In fact, Jackie Robinson called himself a “Rockefeller Republican,” and served as Special Assistant to the Governor for Community Affairs during Nelson Rockefeller’s 1966 reelection campaign.

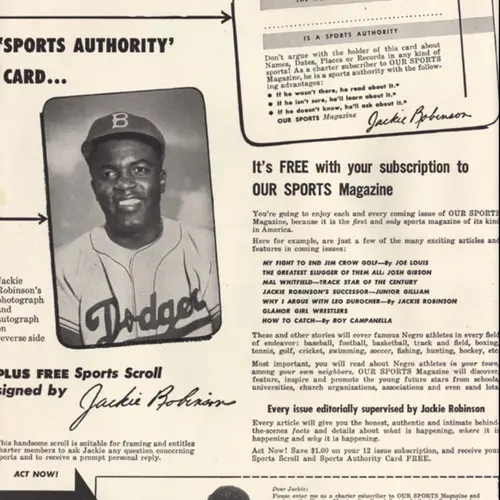

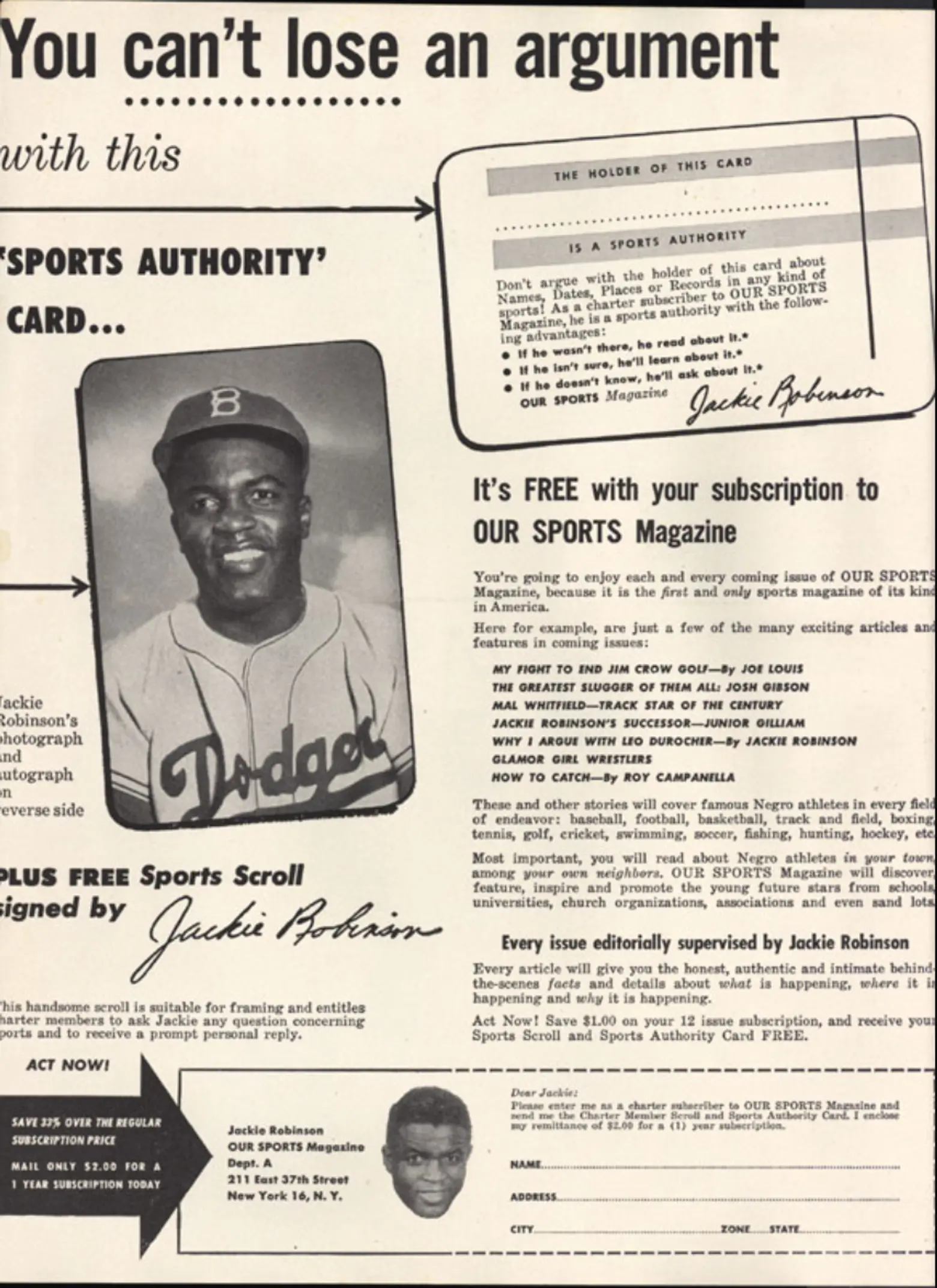

Our Sports Magazine, June 1953 via The Library of Congress

5. 211 East 37th Street

In 1953, Robinson also began editing “Our Sports,” a short-lived magazine focused on black athletes. Charter subscribers to the magazine received a free scroll signed by Jackie Robinson, and were entitled to “ask Jackie any question concerning sports and to receive a prompt personal reply.” They need only write Jackie Robinson, Dept. A, Our Sports Magazine, 211 East 37th Street!

Robinson wasn’t the only star contributing to the magazine. Joe Louis detailed “My Fight to End Jim Crow Golf,” and Robinson’s fellow Dodger, Roy Campanella, explained “How to Catch.” In fact, the magazine promised, readers would be so well-versed in all things athletic, a subscriber’s card warned, “Don’t argue with the holder of this card about Names, Dates, Places or Records in any kind of sports! As a charter subscriber to Our Sports Magazine, he is a sports authority.”

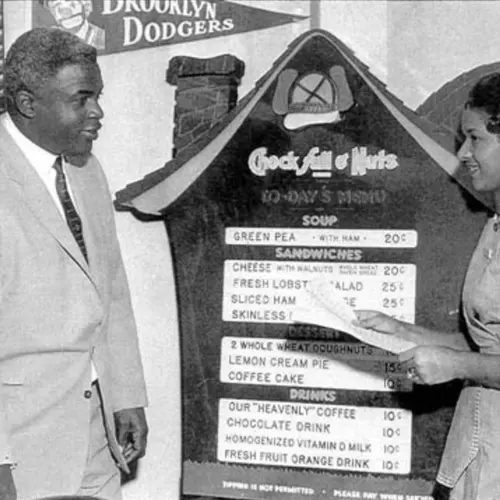

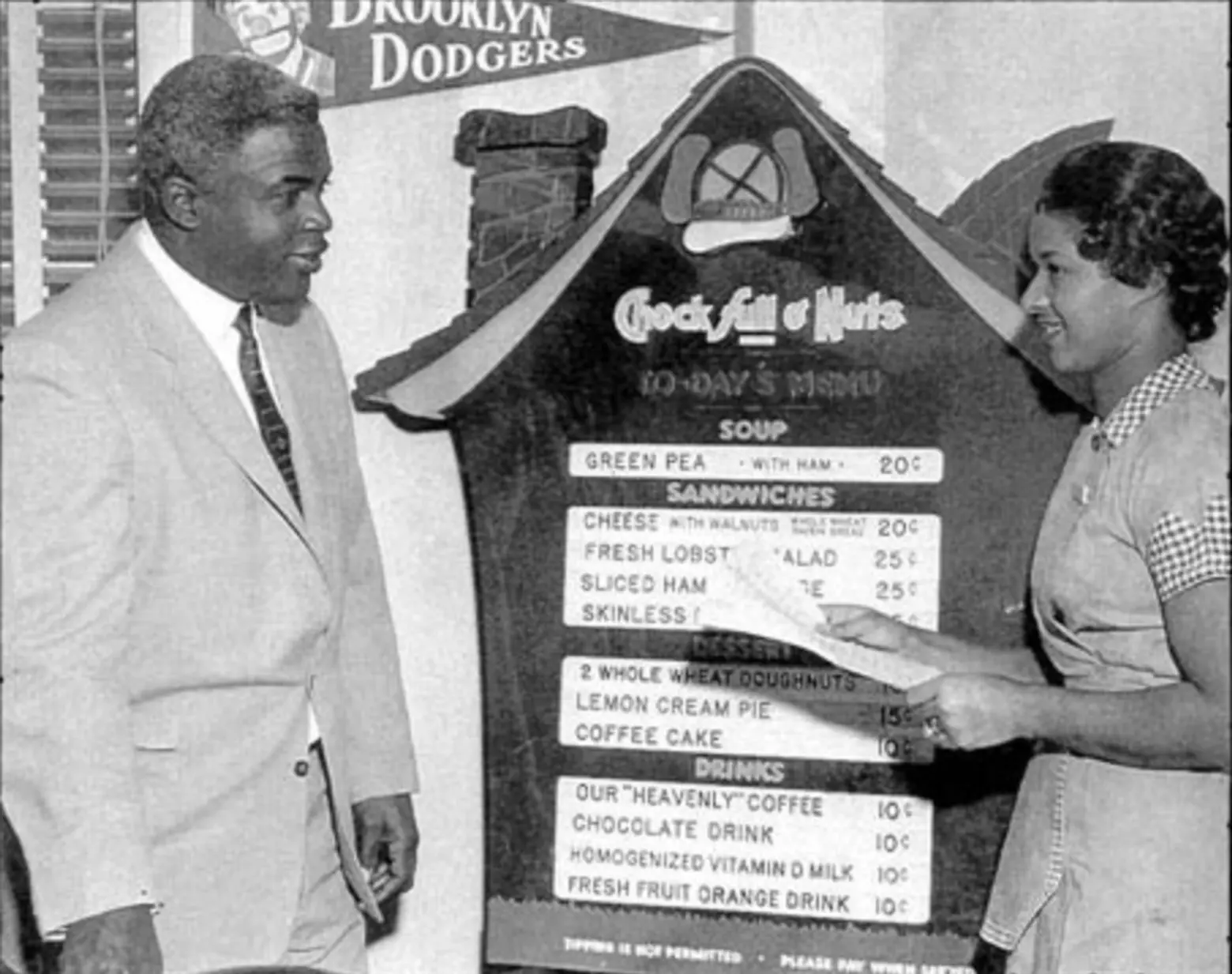

Via the Jackie Robinson Educational Archives at UMass Amherst

6. 425 Lexington Avenue

In 1957, Jackie Robinson broke barriers again. That year, he became Vice President of Chock full o’Nuts. In that post from 1957-1964, he was the first African American officer of a national corporation. From the Chock full o’Nuts office at 425 Lexington Avenue, Robinson carried on extensive correspondence with a succession of presidents, writing as a prominent and passionate Civil Rights advocate.

On May 13, 1958, he wrote Eisenhower, “I was sitting in the audience at the Summit Meeting of Negro Leaders yesterday when you said we must have patience. On hearing you say this, I felt like standing up and saying ‘Oh no! Not again.’…17 Million Negroes cannot do as you suggest and wait for the hearts of men to change. We want to enjoy now the rights that we feel we are entitled to as Americans. This we cannot do unless we pursue aggressively goals which all other Americans achieved over 150 years ago.”

Three years later he wrote Kennedy, “I thank you for what you have done so far, but it is not how much has been done but how much more there is to do. I would like to be patient Mr. President, but patience has cost us years in our struggle for human dignity. I will continue to hope and pray for your aggressive leadership, but will not refuse to criticize if the feeling persist that Civil Rights is not on the agenda for months to come.”

Grand opening of the Freedom National Bank, 1964 via the Jackie Robinson Educational Archives at UMass Amherst

Grand opening of the Freedom National Bank, 1964 via the Jackie Robinson Educational Archives at UMass Amherst

7. 275 West 125th Street

As a black business leader, Jackie Robinson was an advocate for black-owned business, and for black homeowners. To help local African Americans secure small-business and home loans, he co-founded the Freedom National Bank in Harlem in 1964. The bank, headquartered at 275 West 125th Street, was one of the largest black-owned banks in the United States and served the Harlem community until 1990.

Penn Plaza via Wiki Commons

Penn Plaza via Wiki Commons

8. 2 Penn Plaza

Robinson’s contributions to New York’s financial wellbeing did not end there. In 1966, he was elected a Trustee of the Citizen’s Budget Commission, a non-profit, non-partisan civic organization devoted to preserving the city’s public resources for the benefit of future New Yorkers. Today, the Commission has offices at 2 Penn Plaza.

Riverside Church via Wikimedia Commons

9. Riverside Church

Jackie Robinson accomplished an extraordinary amount in a very short time. His remarkable life came to a close October 24th, 1972, when he was just 53 years old. 2,500 people attended his funeral at Riverside Church, where Rev. Jesse Jackson delivered the eulogy. Tens of thousands of people turned out along the procession route to Cypress Hills Cemetery.

Buried in Brooklyn, where he was so beloved, Robinson was laid to rest alongside his mother-in-law Zellee Isum, and his son, Jackie Robinson Jr.

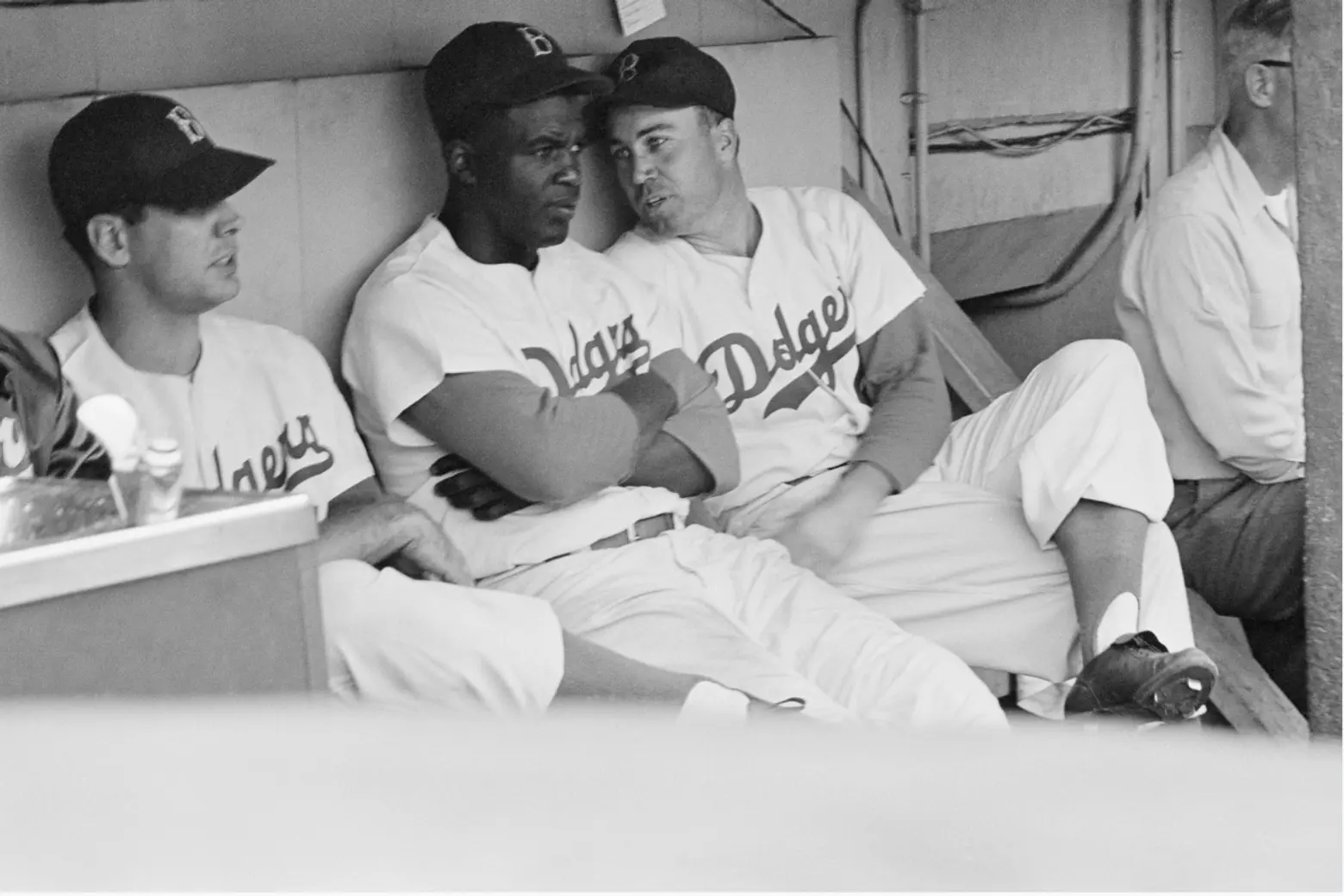

Robinson in conversation with Duke Snider, 1953, photo by Kenneth Edie, Courtesy of MCNY, LOOK Collection

10. 75 Varick Street

Street After Jackie Robinson’s death, his widow, Rachel Robinson, founded the Jackie Robinson Foundation. The foundation celebrates Robinson’s legacy and provides college scholarships and leadership programs for minority students. In 2017, the Foundation broke ground on the Jackie Robinson Museum at 75 Varick Street. The Museum will serve as a tribute to Robinson’s path-breaking role in American history, and honor his commitment to service and advocacy, by providing a venue for social dialog, cultural programming, and education.

RELATED:

- Preserved Stuyvesant Heights Brownstone Was Jackie Robinson’s First Home in Brooklyn

- When the Bronx Bombers were the Highlanders: A brief history of the Yankees

- How the 1919 World Series was rigged at the Upper West Side’s Ansonia

+++

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.