From beavers to banned: The history of New York City’s fur trade

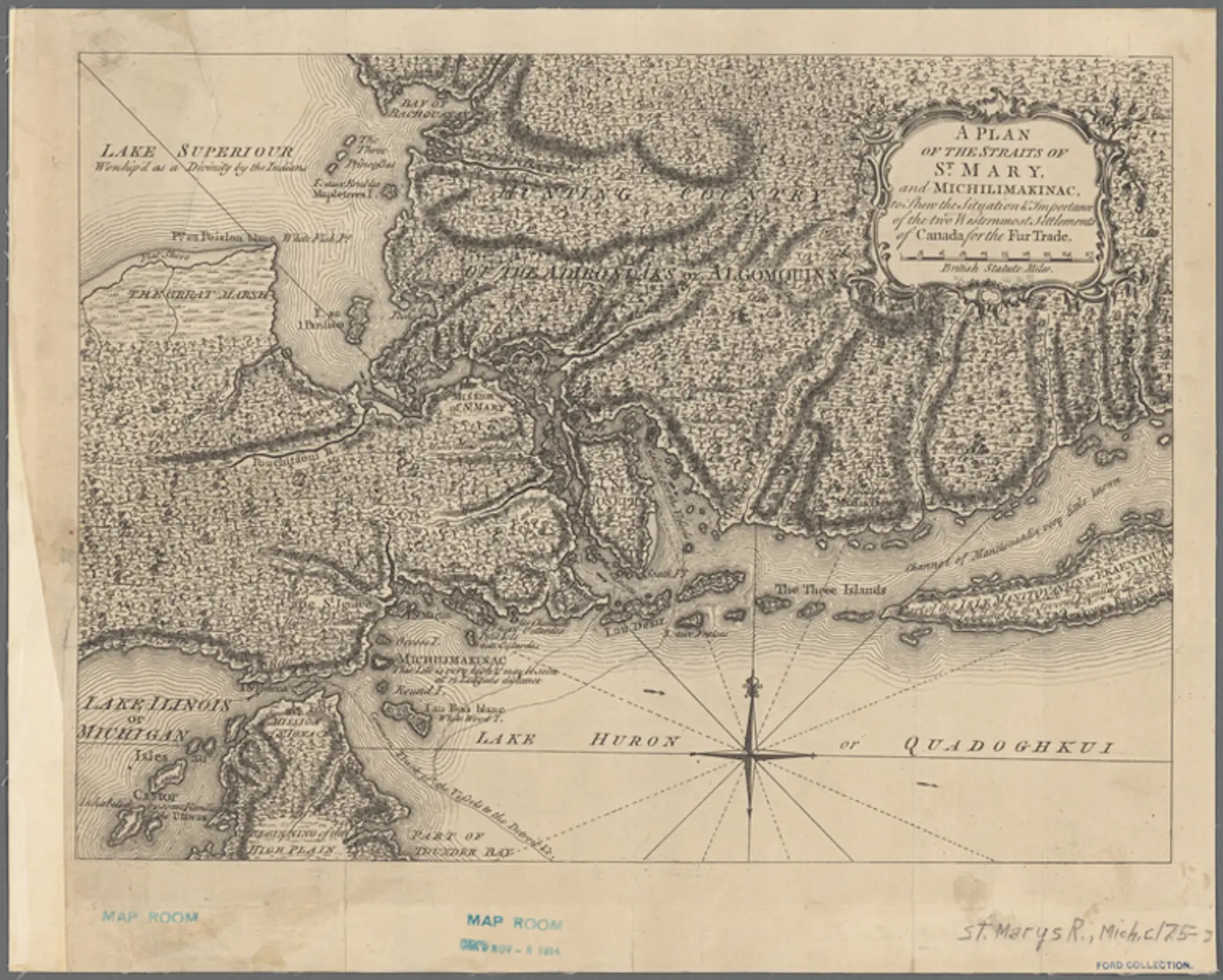

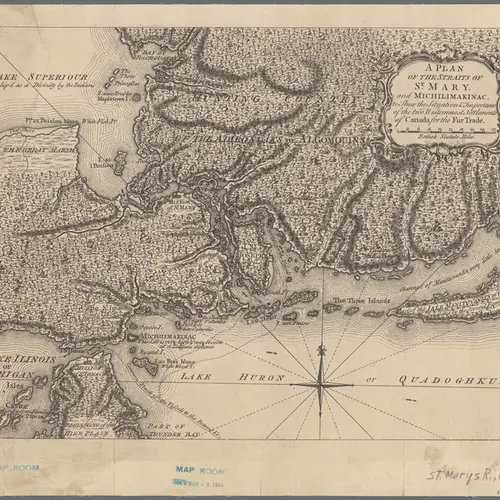

Map of the Western Canadian Fur Trade, ca. 1750-1759. The North American Fur Trade Began with French Merchants in Canada. Via NYPL Digital Collections

The fur trade has such deep roots in New York City that the official seal of the City of New York features not one but two beavers. Fur was not only one of the first commodities to flow through the port of New York, helping to shape that port into one of the most dynamic gateways the world has ever known, but also, the industry had a hand in building the cityscape as we know it. John Jacob Astor, the real estate tycoon whose New York holdings made him the richest man in America, began as an immigrant fur trader. Later, as millions of other immigrants made the city home, many would find their way into the fur trade, once a bustling part of New York’s sprawling garment industry. Today, as the nation’s fashion capital, New York City is the largest market for furs in the United States.

A new bill sponsored by Council Speaker Corey Johnson could change that. Aimed at protecting animals from cruelty, the bill would ban the sale of new fur garments and accessories, but allow for the sale of used fur and new items made out of older repurposed furs. The measure has drawn impassioned criticism from a diverse set of opponents, particularly African American pastors who point out the cultural importance of furs within the black community, and Hasidic rabbis, who worry that wearing traditional fur hats would make Hassidic men vulnerable to hate crimes. And those in the fur industry fear the loss of livelihoods and skilled labor. After prompt pushback, Johnson said he plans to rework the bill to make it more fair to furriers. But given New York’s current debate around fur, we thought we’d take a look at the long history of the city’s fur trade.

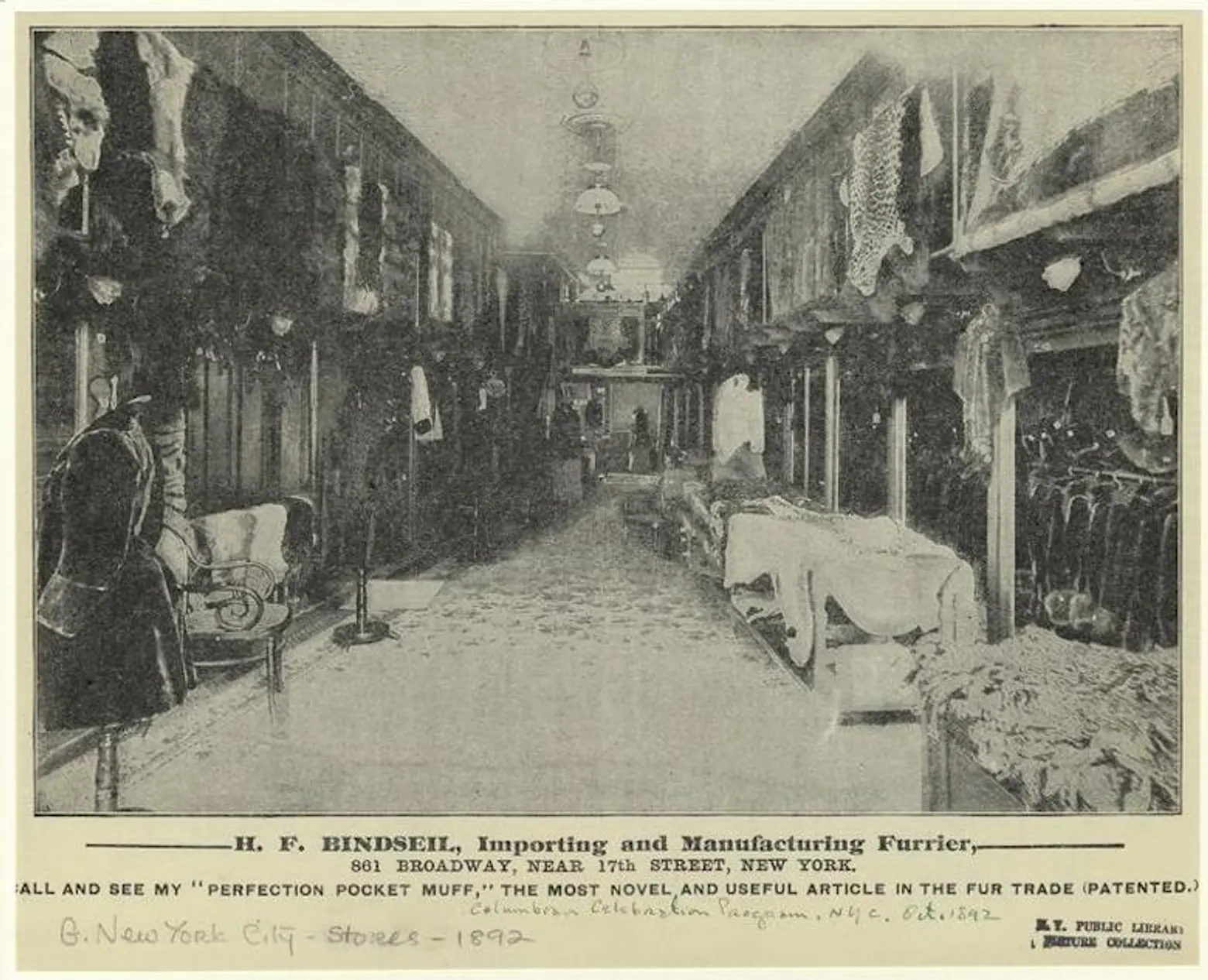

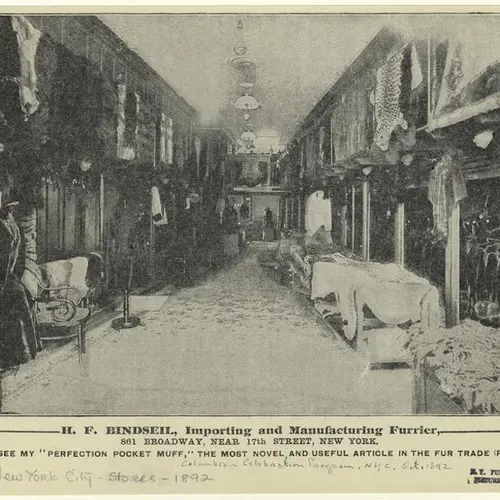

Inside a furrier’s on Broadway, 1892, via NYPL

The North American fur trade predates Henry Hudson’s 1609 arrival in what would become New York. When Hudson came ashore in the New World, he found French traders bartering with Native American trappers for furs. This particular moment of European conquest was driven by a hunger for pelts that the forests of Europe and Asia could not satisfy. By the 17th century, beaver had been hunted nearly to extinction on those continents but seemed in boundless residence in the forests of North America.

Accordingly, New Amsterdam became a Dutch fur trading post. In 1670, shortly after New Amsterdam had become New York, the British chartered Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), which now owns Saks Fifth Avenue and Lord & Taylor. HBC established a British fur business throughout what is now Canada and wrested dominance over the North American fur trade from the French. HBC retained that dominance until a German immigrant to New York decided the make the North American fur trade All-American.

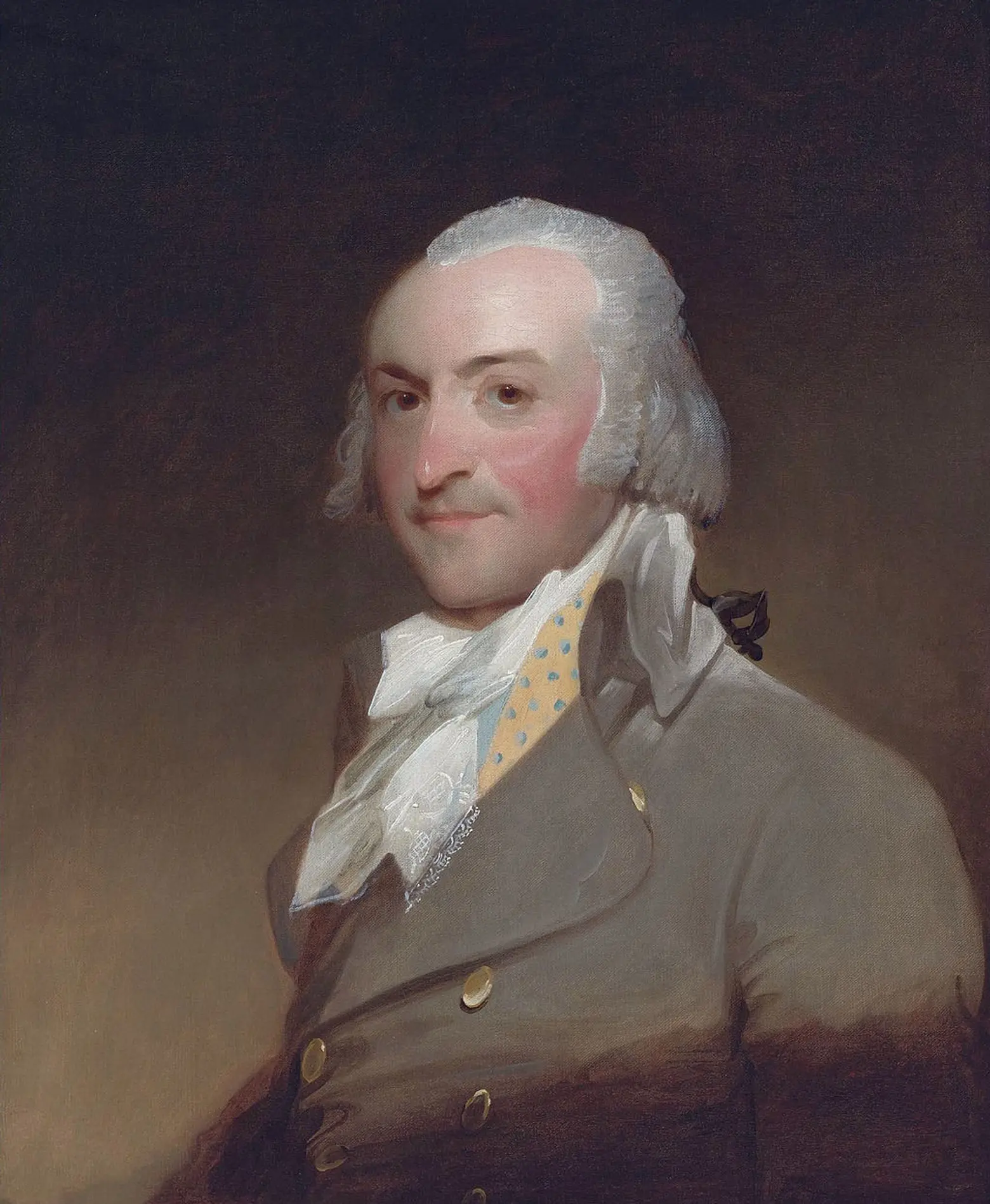

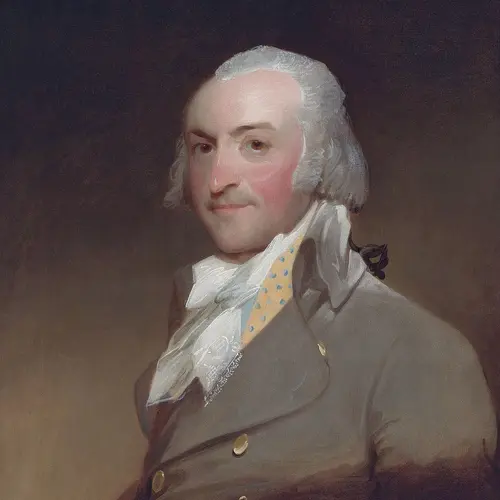

This brings us to John Jacob Astor. Astor was born in Walldorf, Germany. He founded the American Fur Company in New York City in 1808. Capitalizing on Anti-British sentiment in the new American republic, Astor built a company that grew to rival then overtake HBC, and that emerged as one of the first Trust-style business ventures in the United States. By 1830, Astor controlled virtually the entire American fur trade, but bowed out of the company in 1834, using the money he gained from its sale to buy huge tracts of land in New York.

John Jacob Astor, via Wiki Commons

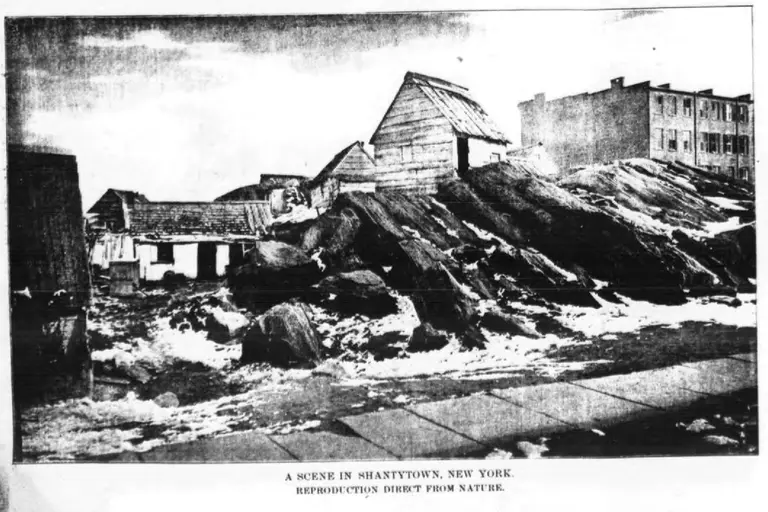

So, pelts turned into lots, and John Jacob Astor became New York’s chief landlord-slumlord-hotelier. Taking in the splendor of the Astor House Hotel, frontiersman Davy Crockett remembered that pelts had paid for it. He exclaimed, “Lord help the poor bears and beavers!”

John Jacob Astor died in 1848 as the richest man in America. His meteoric immigrant success story is a nearly-foundational example of the American Dream. As millions of other new Americans arrived in New York, some, like Astor, joined the fur trade.

By the late 19th century, the fur trade in New York City was one of many needle trades in New York’s bustling garment industry. But, unlike the grinding piecework that plagued workers’ days at such deathtrap-sweatshops as the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, furriers were skilled artisans, who had learned both a trade and a craft. That skill came courtesy of places like Textile High School on 18th Street, or Central Needle Trades High School on 24th Street; alternatively, a furrier might learn his craft as an apprentice in the Fur District, where many of the businesses were, and remain intergenerational, family-owned enterprises.

The Fur District thrived from 27th to 30th Streets, between 6th and 8th Avenues, where hundreds of furriers, and fur related companies, lined the streets. As New York emerged as the capital of arts, culture, and glamour in 20th century America, New Yorkers turned to fur to advertise a new level of wealth and status.

In the African-American community, where redlining, housing discrimination and other forms of structural inequality prevented black families from homeownership and wealth-building, items like a fur coat emerged as markers of personal prosperity, that could also be passed down from generation to generation. In the 1920s the leading lights of the Harlem Renaissance used their furs as a new form of creativity and self-expression. In the 1960s, black stars including Diana Ross and Ray Charles appeared in advertising campaigns for mink coats.

A woman in fur, via The National Museum of African American History and Culture

Since the 1980s, New York’s fur district has been shrinking. In 1979, the district had 800 manufacturers. By 1989, there were 300. Today, the city is home to 150 fur businesses that represent 1,100 jobs. At the same time, the fur district has gone from manufacturing a luxury product to offering luxury amenities. Hotels, condos, restaurants, and rentals have replaced furriers, who were booted out on the tails of rent increases.

Despite the fur industry’s decline, New York still remains its largest domestic market. Here, fur stands out as an item of cultural, social, economic and religious importance to an array of New Yorkers as diverse as the city itself.

+++

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Get Insider Updates with Our Newsletter!

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

the history of fur business New York city