From sea hospitals to sanatoriums: How NYC has contained contagious diseases over the last century

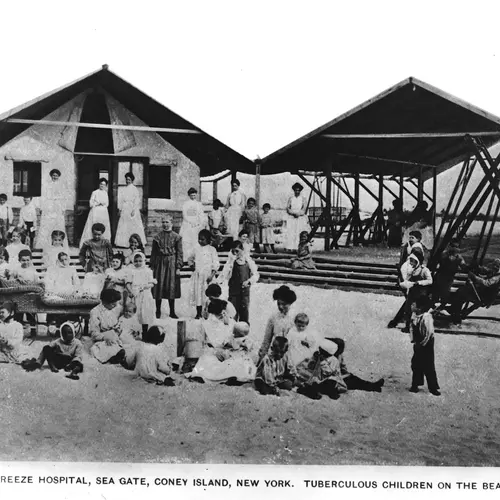

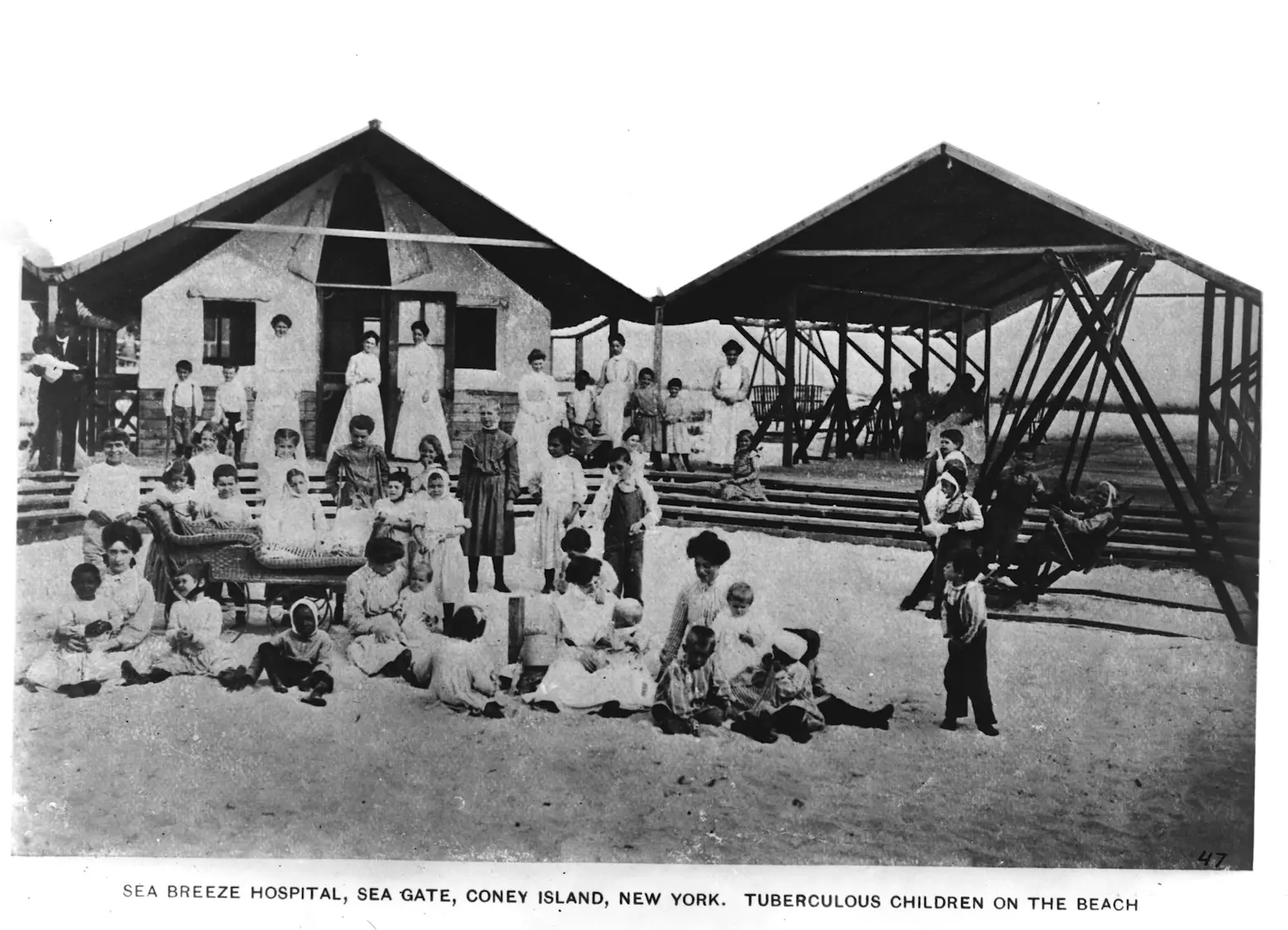

Sea Breeze Hospital in Coney Island via Library of Congress

At a press conference on Monday about the recent coronavirus cases confirmed in New York City and State, Governor Cuomo and Mayor de Blasio emphasized that this is not New York’s “first rodeo” when it comes to pandemics. They pointed to the recent Ebola scare, as well as the 1968 Hong Kong flu and the 2009 Swine Flu, which closed 200 schools across the state. But even long before that, New York has had a gold standard for handling outbreaks of contagious diseases. From managing the flu pandemic of 1918 to the tuberculosis surge at the turn of the 19th century, the city’s public health officials have been containing outbreaks for well over a century. Ahead, we look at some of the ways this done, from quarantines to sea hospitals.

A typist in NYC wears a mask while working, via Wikimedia Commons

Quarantines

Two years ago marked the centennial of the 1918 flu pandemic. In the end, the pandemic took anywhere from 500,000 to 1 million people’s lives worldwide. Somewhat remarkably, despite being a major port, only about 20,000 New Yorkers’ lives were lost. While 20,000 lives lost is still a high death toll, compared to many other U.S. cities, New York suffered fewer losses.

Historians suggest that New York’s proportionately lower death toll during the 1918 flu pandemic had much to do with the health department’s rapid response, which included imposing a strict quarantine on anyone who was found to have the flu. When cases developed in boarding houses or tenements, the city went a step further and removed the patients to a city hospital where they were held under observation and treated.

The city also was proactive in educating its residents. The Health Department distributed thousands of leaflets (which included 900,000 to every single public and private school student in the city) with guidelines that told people to use handkerchiefs when they coughed or sneezed, stop spitting, and to avoid crowds. Lillian Wald, who founded the Henry Street Settlement in 1893, which would ultimately lead to the creation of the Visiting Nurse Service, helped to create the Nurses Emergency Council, which “brought together all of the private nursing agencies and City inspectors,” according to the NYC Department of Records & Information Services.

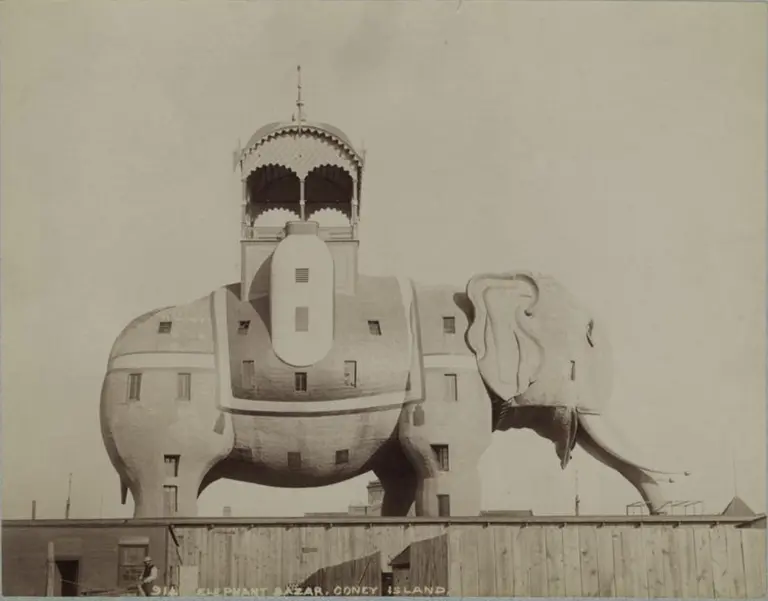

Shipping was also a major concern at the time, and quarantine measures were put in place for those entering New York Harbor. Another interesting way the city responded was to put in place staggered work hours; different types of businesses (finance, retail, etc.) would start work at different times to avoid a typical rush-hour situation on the subway. Surprisingly, theaters and public spaces remained opened, as Health Commissioner Royal Copeland felt that these places were often more sanitary than one’s own home, likely referring to the thousands of New Yorkers living in cramped, dark tenements.

A dormitory at the Municipal Lodging House via Library of Congress

As 6sqft previously noted, Health Commissioner Royal S. Copeland told The New York Times on September 19, “When cases develop in private houses or apartments they will be kept in strict quarantine there. When they develop in boarding houses or tenements they will be promptly removed to city hospitals, and held under strict observation and treated there.”

But as confirmed flu cases soared and exceeded the capacity of local hospitals, the Municipal Lodging House on East 25th Street, the city’s first homeless shelter, was converted into a care facility. But the flu pandemic of 1918 wasn’t the first or only contagion that has challenged city health officials over the past century.

The Adirondack Cottage Sanatarium in Saranac Lake, NY; via Library of Congress

Upstate sanatoriums and sea hospitals in Coney Island

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, New York City health officials frequently found themselves battling outbreaks of contagious diseases. Among the most common was tuberculosis. Between 1810 and 1815, tuberculosis accounted for 25 percent of deaths in New York City and by 1900, it was still the third most common cause of death in the United States. By the early 20th century, however, researchers had discovered the tubercle bacillus. As knowledge of germs and how they spread increased, medical practitioners came to appreciate that isolation was a key part of prevention, but when it came to tuberculosis, some forms of isolation proved more effective than others.

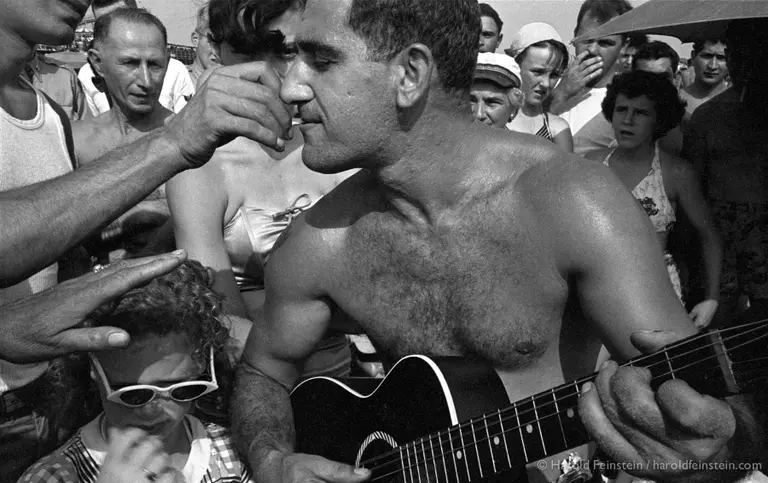

Children with nurses at “Sea Breeze Junior”; via Library of Congress

Patients who lived in locations with lots of fresh air, sunlight, rest, and nourishing food were found to fare much better than patients left in dark rooms with little fresh air. This realization led to the construction of sanatoriums. One of the first sanatoriums in the United States was the Adirondack Cottage Sanatorium. Since not everyone could afford to leave the city, however, by the early twentieth century, solutions were being constructed closer to home—this included a “sea hospital” at Coney Island known as the Sea Breeze Hospital. It opened in 1902 in a tiny wooden building.

A child with tuberculosis sitting outside of Sea Breeze Hosptial; via Library of Congress

The Sea Breeze Hospital, which operated for roughly three decades, was built for poor children, and in some cases, also for their mothers. Since most children who ended up at the Sea Breeze Hospital had to stay for months and often years, the hospital operated as a separate community and even had its own school.

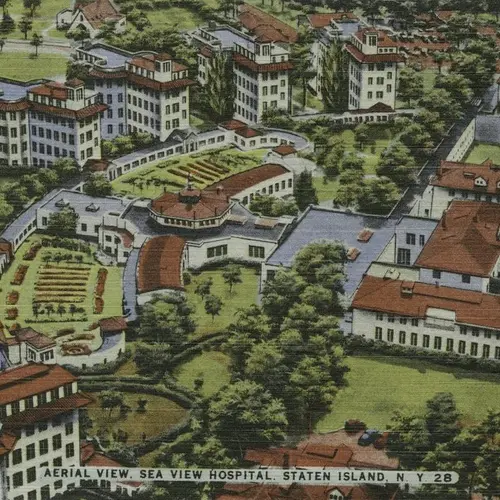

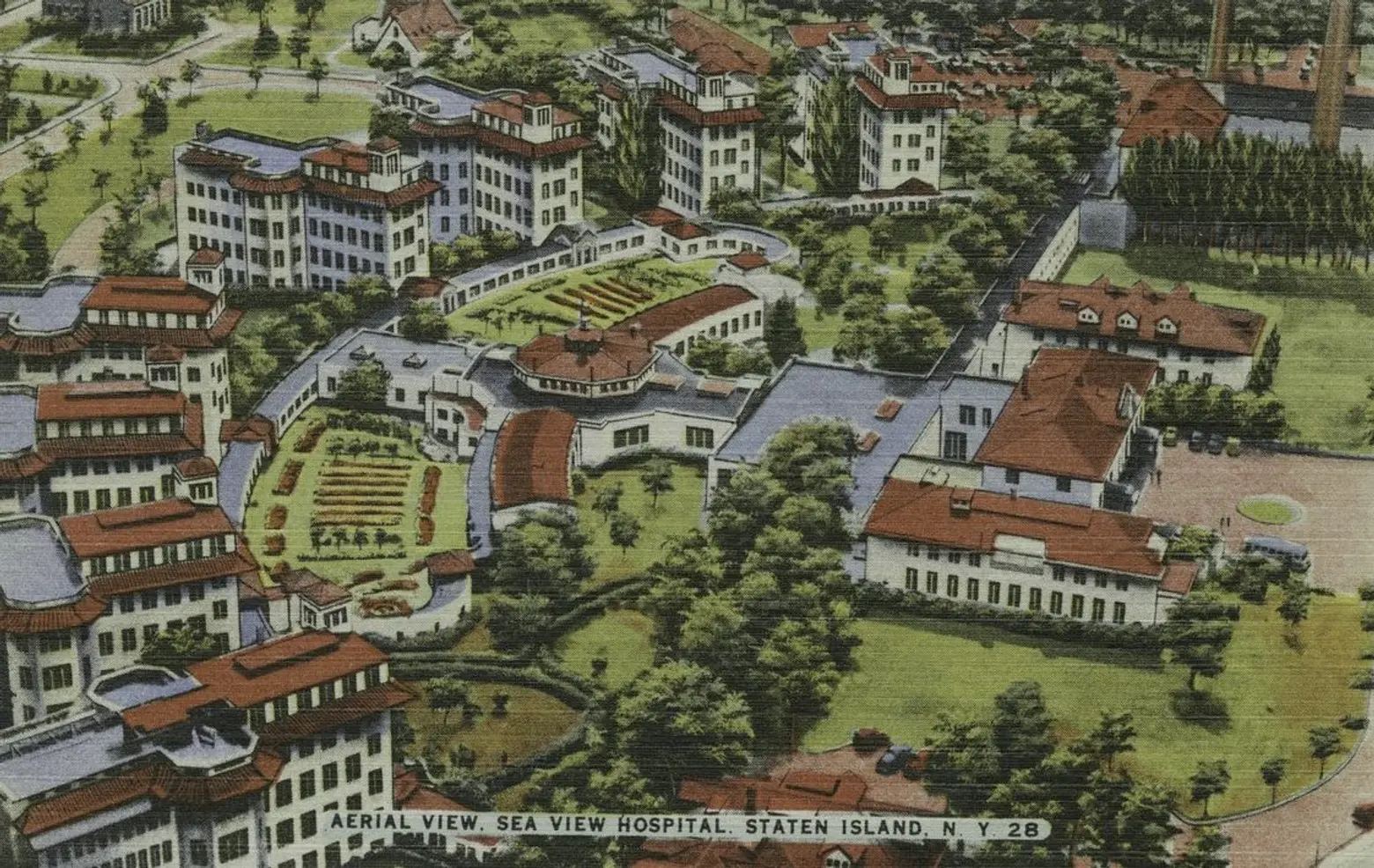

Photo via Wikimedia Commons/NYPL Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy

Another hospital was built on Staten Island by 1938. Called Seaview Hospital, it was the largest and most expensive municipal tuberculosis facility in the country. It was so large, in fact, that its 37 buildings today make up their own city-designated historic district. As Untapped Cities tells us, in the 1950s, “Sea View hospital was the site of the first clinical trials for hydrazides treatments, which ultimately led to the cure of the disease.” It’s currently a rehab center and nursing home.

Editor’s Note: This story was originally published on July 5, 2019.

RELATED: