From shipping hub to waterfront wonder, the history of Brooklyn Bridge Park with Joanne Witty

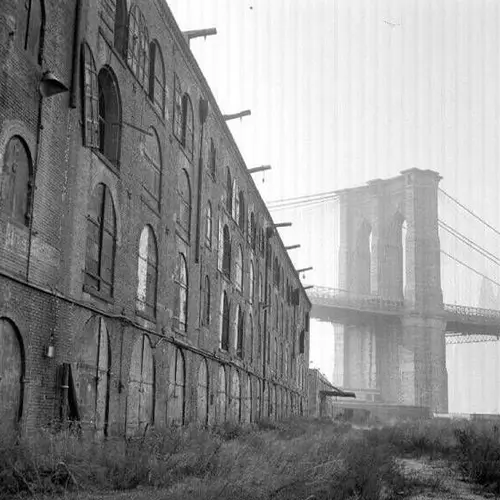

134 years ago, the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge transformed the Brooklyn waterfront, not to mention the entire borough, by providing direct access into Kings County from Lower Manhattan. The opening only boosted Brooklyn’s burgeoning waterfront, which became a bustling shipping hub for the New York Dock Company by the early 1900s. Business boomed for several decades until changes in the industry pushed the shipping industry from Brooklyn to New Jersey. And after the late 1950s, when many of the warehouses were demolished to make way for construction of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, the waterfront fell into severe decline.

New Yorkers today are living through a new kind of Brooklyn waterfront boom, heralded by the Brooklyn Bridge Park. Ideas to transform the abandoned, run-down waterfront into a park seemed like a pipe dream when the idea was floated in the 1980s, but years of dedication by the local community and politicians turned the vision into reality. Today, the park is considered one of the best in the city.

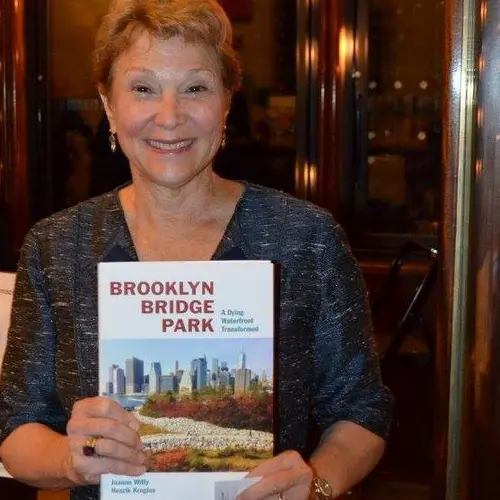

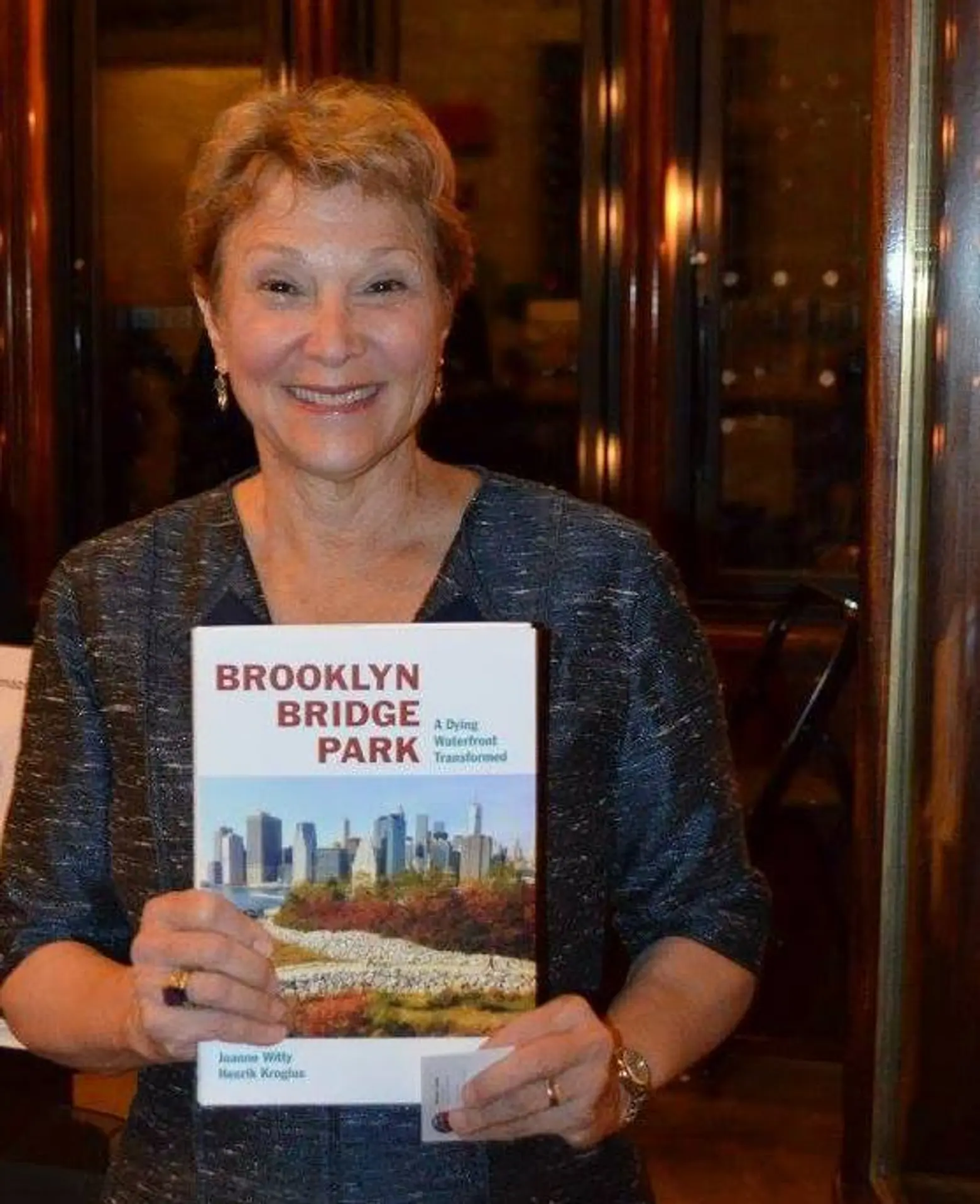

Perhaps nobody knows what went into its development better than Joanne Witty, the first president of the park’s Local Development Corporation. The group was established to put plans for waterfront development in motion. Witty, with a background in law and environmentalism, helped push through the long, arduous, extremely complex and extremely rewarding process. The experience was so influential Witty took her knowledge and wrote Brooklyn Bridge Park, A Dying Waterfront Transformed with co-author Henrik Krogius to make sense of why and how the park came to be.

Perhaps nobody knows what went into its development better than Joanne Witty, the first president of the park’s Local Development Corporation. The group was established to put plans for waterfront development in motion. Witty, with a background in law and environmentalism, helped push through the long, arduous, extremely complex and extremely rewarding process. The experience was so influential Witty took her knowledge and wrote Brooklyn Bridge Park, A Dying Waterfront Transformed with co-author Henrik Krogius to make sense of why and how the park came to be.

As the book description notes, “the park’s success is no accident.” Witty and Krogius interviewed more than 60 people to highlight the role of people power—from community planners, park designers to political leaders—throughout the process. And Witty played a central role in organizing those many voices. With 6sqft, she discusses the history of the waterfront, the controversies surrounding the park, and the biggest lessons she learned along the ride.

+++

How long have you been in Brooklyn?

Joanne: I’ve been living in Brooklyn since 1980. I first lived in Cobble Hill, and now live in Brooklyn Heights.

So what initially drew you to the waterfront?

Joanne: I lived on Roosevelt Island for about five years previously. I was working for the city and the state and then went to law school. When we left Roosevelt Island we were trying to figure out where to go. Manhattan was expensive and dirty, and my husband wanted to go somewhere different from where we’ve been living. We opened the New York Times and I looked in Brooklyn, and we fell in love.

Now, we’re half a block from the Squibb Park Bridge, and we look out on the park. I could see the park during its entire development. I’ve really liked being nearby, to see what’s happening.

What was the state of the waterfront, before it became a park?

Joanne: Part of the waterfront that’s now the park was a shipping facility for many years. The New York Dock Company was very active at 360 Furman Street, its world headquarters was the building that’s now One Brooklyn Bridge Park. They were the largest private shipping company in the world, at one point. Then the Port Authority acquired all their facilities and became the owner.

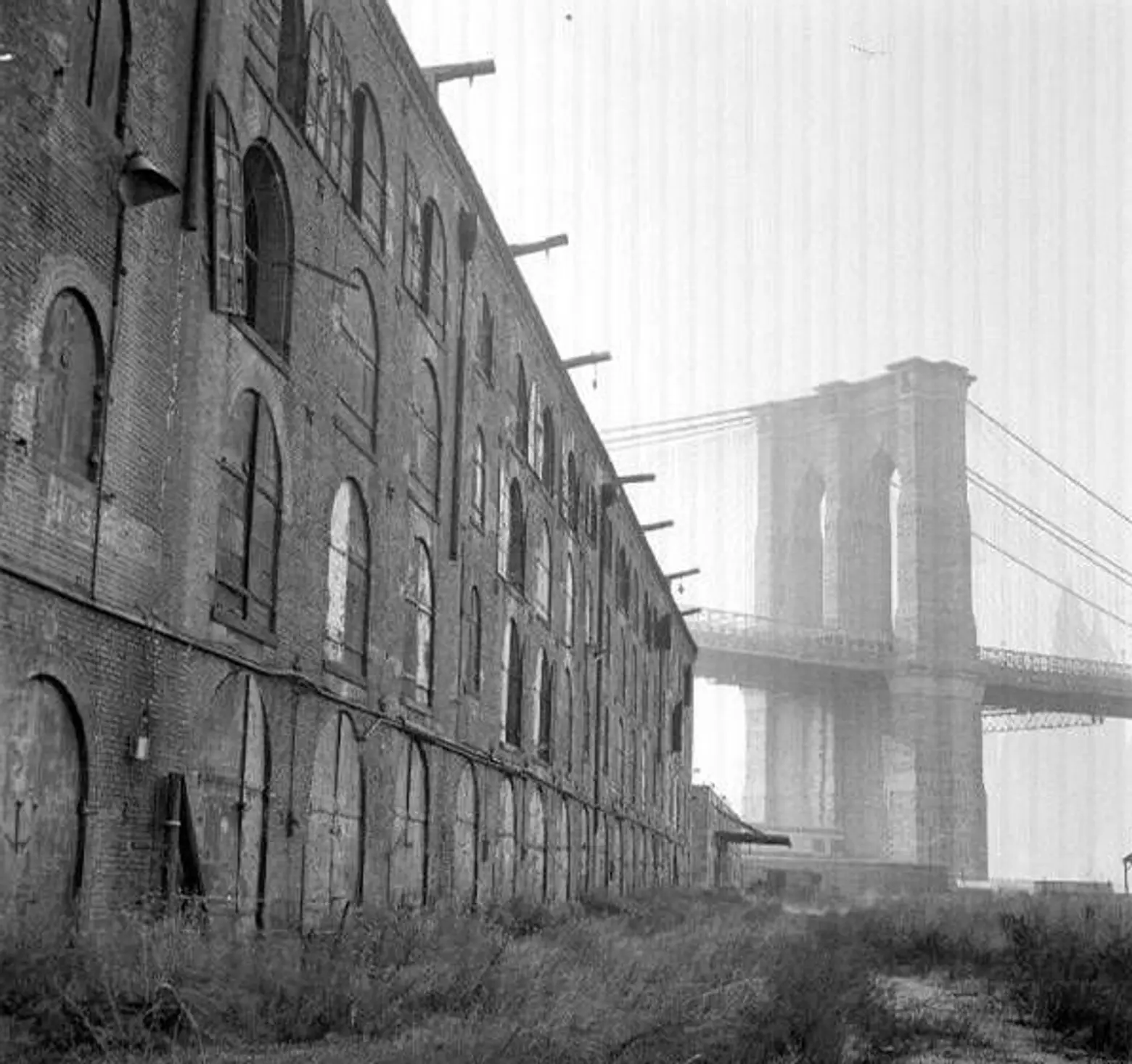

But what happened to shipping in New York, not just Brooklyn, was the advent of containerization. It started in the 1950s but became the gold standard of shipping in the 70s. Previously, boats were filled with sacks—Brooklyn was the largest port in cocoa and in coffee and tobacco. Stevedores would go down into the hole, pull the sacks out, and there was a pulley system put into the warehouses along the water. They were called “stores” which is how we get the Empire Stores.

But all of a sudden, containers became the way things were moved from place to place. In order to be a successful shipping port, you needed a lot of land adjacent to the slips where you stacked up containers as they came off the boat. Along the Brooklyn waterfront, while the water is quite deep, there’s not much of it. It quickly became clear the Brooklyn piers would not be part of a major container port, whereas New Jersey had a lot of vacant land along the water and the Port Authority decided to build the port there.

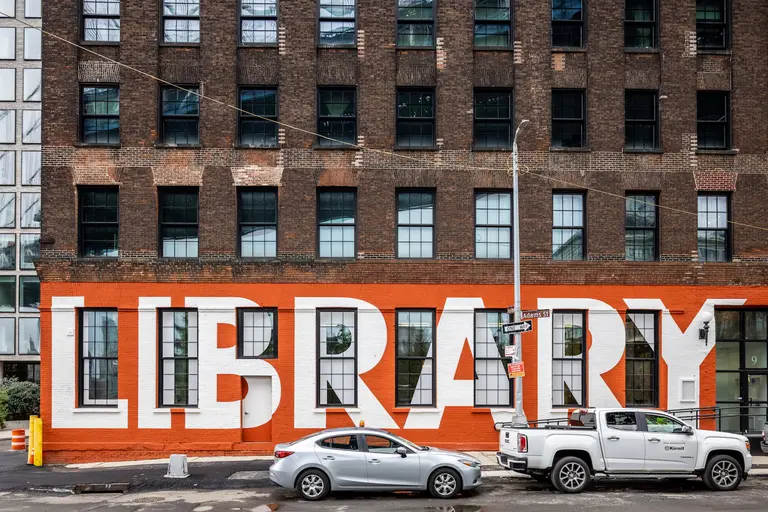

The Empire Stores sat abandoned after the shipping industry left the waterfront

The Empire Stores sat abandoned after the shipping industry left the waterfront

Then that area gets transformed by Robert Moses.

Joanne: Robert Moses built into Brooklyn Heights with his cantilevered highway, with the promenade on top. So there was nowhere to go with those containers. Pretty soon, those piers became obsolete. In the early 80s, the Port Authority declared them no longer of use to them. I think they felt it was quite a beautiful site, although it would need to be transformed in some way. There was an idea to monetize the site and thought, initially, that selling it to developers was the best way to maximize their investment.

So when is this happening?

Joanne: In the 80s, the Port began talking to developers. They were talking about connecting the site back up to Brooklyn Heights—it had previously been connected before the BQE went in. Brooklyn Heights was isolated from the piers and became even quieter than it was before. But the neighborhood liked it. So when the Port Authority wanted to develop the piers and create a new connection, the Brooklyn Heights community did not like it one bit and opposed the Port Authority plan.

Eventually, the Brooklyn Heights Association hired planners, created a coalition, and came up with an alternative idea. One of the schemes was a park and only a park. Most of the schemes involved a mix of things, as they didn’t think a dedicated park could be financially feasible. But the communities liked the idea of only a park…why not?

The question of who the park was for, what would be in the park, who would pay for it, all those issues were left totally up in the air. In the 90s, they came around to the idea of generating income for the park with the Borough President. He was interested in a park, but something else. He wanted it to be an asset for the whole borough, for those who didn’t necessarily have access to parks and to generate more economic activity.

After 10 years of stalemate, the Borough President created the Local Development Corporation. The idea was the group would talk to the Port Authority and the community to reach some sort of a deal. I ended up as the President of the Local Development Corporation. We went straight to the Port Authority and asked them not to do anything with these piers as we worked on ideas.

What we eventually proposed to them was a very public planning process. We wanted to talk about this resource available and what it might be—we wanted to hear what people from all over thought. We saw this as an asset for the whole borough, not just a neighborhood park.

Tell me more about your role as president.

Joanne: I worked in the budget bureau in the Lindsay administration, and then worked in state government, then went to law school. I practiced law, spent five years at the Ford Foundation, and was also an environmentalist on the board of the Environmental Defense Action Fund. I had a broad background, but stopped working after I had kids when I was 40. [The Local Development Corporation] was looking for someone with no previous experience on this issue, at all, because there was some baggage attached to the project at that point.

There were 15 of us, and a pretty broad community representation. I left the Local Development Corporation after the plan was done, in 2000. In 2002, the city and state created a joint organization under the Empire State Development Corporation. I became a member of that board.

How do your earliest visions of what the park could be compare to what it’s become?

Joanne: In the beginning, there was a preference toward a pristine, beautiful place to sit and read a book, much less active. Active versus passive was an issue during the planning process, and there’s only so much land, a little less than 90 acres. There’s not a lot of room to waste in this park. Eventually, we came to the idea of “the water” and it became more and more pronounced. The marine structures were not in good condition, so we decided to take them out and put in rock you now see along the waterfront. It created natural edges of the park, and put people at the level of the water. There are places water passes under people, there’s a beach, you can get really close to the water all along the park.

People came in with a lot of requests for active recreation, a tennis court or soccer field. We tried to design spaces we used for more than one thing. For example, a soccer field could also be a baseball diamond, even a cricket field. The basketball on the pier also has handball courts, weight equipment, an open space at the end of the pier. We also tried to vary the experience, and we worked with our amazing landscape designers to do this. Michael Van Valkenburgh was very much influenced by Olmsted. We tried to do a combination of places where you could just sit, and where you could be very active. We also did programming, like public art, sailing, kayaking.

The park is democratic with a small d. We are drawing people from all over, kids coming from all over the city.

There seem to be controversies and more questions over who the park belongs to, with the addition of luxury housing.

Joanne: I don’t think the housing interferes with the democratic nature of the park. The park cost $400 million to build, and everyone has agreed maintenance and operation would be covered by revenue-generating sources from within the park. Residential housing didn’t enter the picture until much later in the planning, in 2005 when it became clear it would cost $15 million a year to maintain the park.

We knew that couldn’t be provided for by a few restaurants, or a conference center. A hotel was always sort of in the mix on Pier One. But in 2005, to seek the revenue we needed, we went through all the possible choices. At the end of the day, residential was thought to be capable of generating the most revenue in the smallest footprint, and also as “eyes on the park,” keeping it safe.

Only about 6 to 7 percent of the park was dedicated to residential use. Why is it luxury housing? Because you’re trying to raise the most revenue. And we worked with Mayor de Blasio to include affordable housing, too, which was meaningful to him as one of his early projects as mayor.

So at what point did you know you wanted to write a book about all this?

Joanne: Well, I’ve been woking on this park since 1998. It’s now run by the city, who created a nonprofit to run the park, and I’m vice-chair of that. I’ve been on all three entities that have planned and built the park. I’m one of the institutional memories here, and it’s gone through the most amazing twists and turns. It has not been an easy project, it’s taken from the 1980s to 2017, and we’re still arguing.

It’s been government at its best and worst, 9/11, Superstorm Sandy, five governors, four mayors. There’s a public/private component, there’s an unusual funding source, and it’s independent, not part of the Parks Department.

As it all went along, I’d say when something really wacky happened, “That’s going in the book.” It also felt like an important story to tell, because the reclamation of waterfronts is going on all over the country and it’s really complicated. There’s also the human dynamic, how you move people, how you create consensus, how you maintain consensus.

What’s been the biggest lesson after the park development and reflecting on it through the book?

Joanne: I worked with Henrik Krogius, my co-author and the editor of the Brooklyn Heights Press. He was incredibly smart and experienced, and it was so much fun working with him. I wrote most of the book, but he had a journalist’s eye and provided perspective. We worked together for four years, but he died of prostate cancer within a month of when the book published.

I really miss him. We both had the same aim, to tell this story in an interesting way and pick out the themes and talk about broader issues. This whole experience of living through the park and writing the book has taught me so much about people. You can’t do a project like this without people. It wasn’t the same people throughout. But there were so many people who went to meetings, gave us their ideas, and reminded us of what was important. Learning about the role of people in the process to create something important is the most important lesson, for me.

Joanne Witty who is an attorney and co-author of the book, Brooklyn Bridge Park: A Dying Waterfront Transformed. Joanne Witty has been a central figure in the creation of Brooklyn Bridge Park

RELATED: