From Willem de Kooning’s loft to the threat of the wrecking ball: The history of 827-831 Broadway

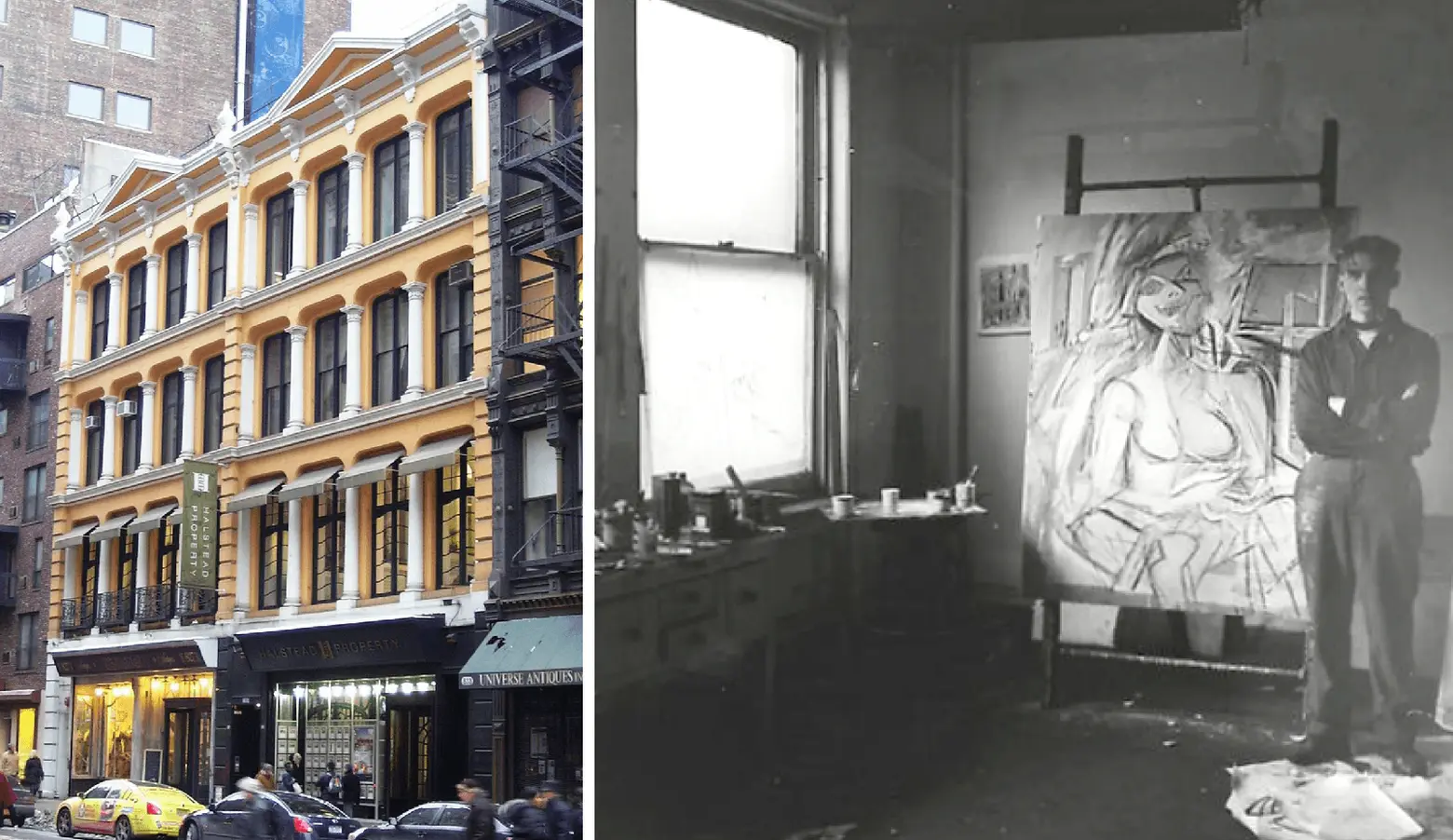

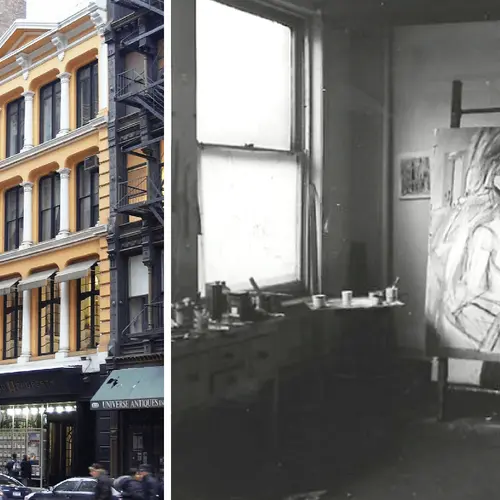

827-831 Broadway today via Wiki Commons (L); Willem de Kooning in his Fourth Avenue studio, April 1946. Harry Bowden, photographer. Harry Bowden papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.Via The Willem de Kooning Foundation. (R)

Underneath the lyrical and much-admired sherbet-colored facades of the twin lofts at 827-831 Broadway lies a New York tale like no other. Incorporating snuff, sewing machines, and cigar store Indians; Abstract Expressionists; and the “antique dealer to the stars,” it also involves real estate and big money, and the very real threat of the wrecking ball. Ahead, explore the one-of-a-kind past of these buildings, which most notably served as the home to world-famous artist Willem de Kooning, and learn about the fight to preserve them not only for their architectural merit but unique cultural history.

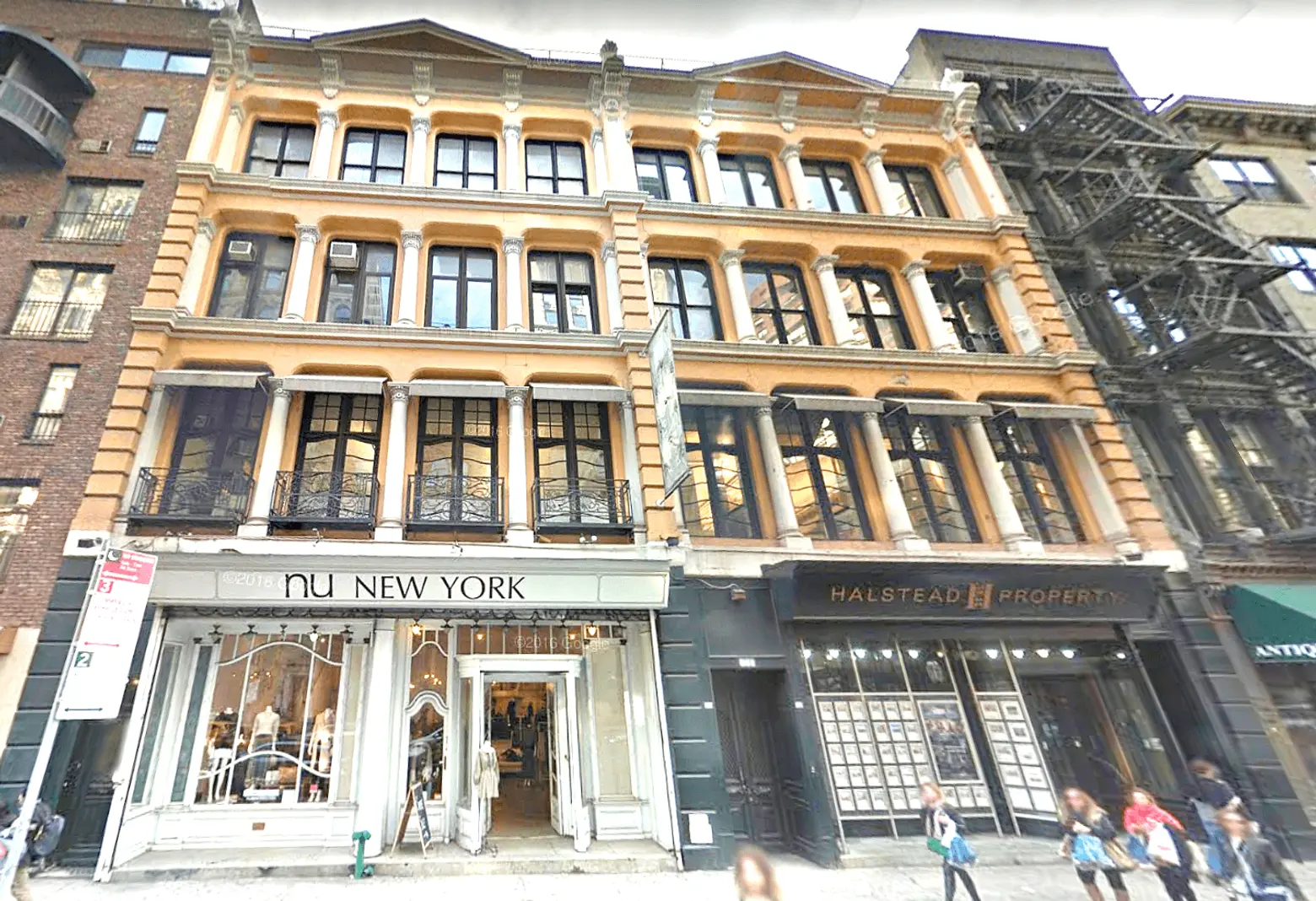

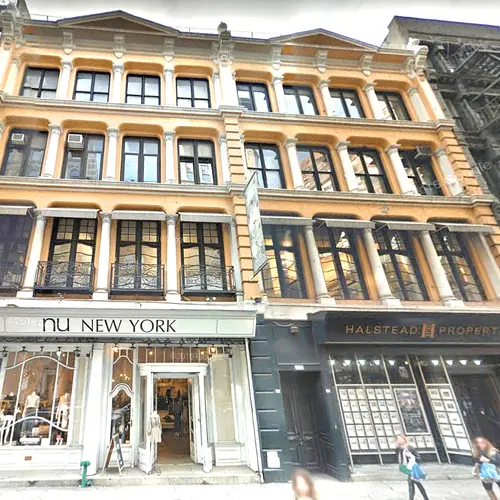

Google Street View of the buildings today

Google Street View of the buildings today

The cast-iron buildings were constructed in 1866 by Pierre Lorillard III, grandson of Pierre Abraham Lorillard, who founded the Lorillard tobacco empire (which eventually became one of the largest tobacco manufacturers in the world) with a factory in Lower Manhattan. Pierre I was the first man to make snuff in North America, but also created what some experts call the “earliest known advertising campaign” by introducing the Lorillard logo of a Native American smoking a pipe beside a hogshead or barrel of tobacco in 1789. The basis for the “Cigar Store Indian,” it was said to be the best-known trademark in the world.

Soon after construction, the buildings served as the headquarters and showroom of Wilson Sewing Machines. Alan Wilson invented some of the first successful sewing machines in 1850, and his company revolutionized the process by which clothing was manufactured and repaired. During the time Wilson Sewing was located here, the company grew exponentially, dramatically changing the landscape of American manufacturing and domestic life. By the late 19th century, the buildings housed A.A. Vantine, which introduced imported crafts from the recently-opened nation of Japan into the United States, and became the number one purveyor of imported Japanese goods in the United States. Vantine soon after added Turkish rugs to his business and became the leading merchant in that field in New York City. Before Times Square became known as the “crossroads of the world,” nearby Union Square and more specifically 827-831 Broadway might have earned that title with its exotic and international assortment of goods for sale.

As the 19th century became the 20th, the area’s fortunes dipped as a once-fashionable shopping district became working-class and then seedy. But in the midst of the grit and decay of late 20th century New York, 827-831 Broadway became the center of an art-world revolution.

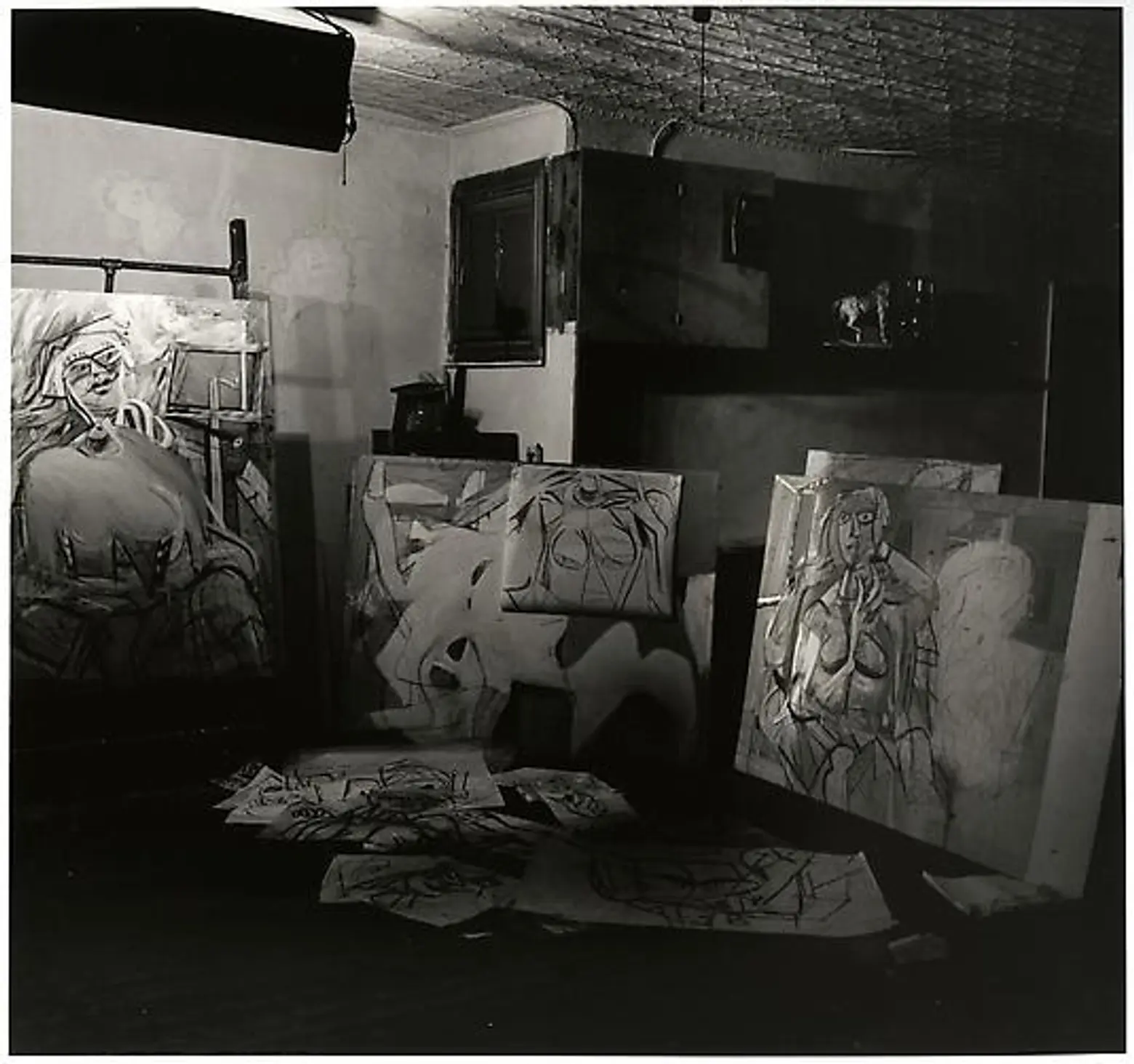

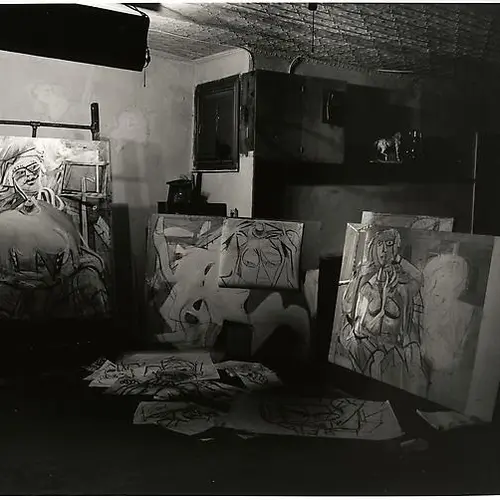

The interior of Willem de Kooning’s Studio, Fourth Avenue, New York City, 1946. Photograph by Harry Bowden. Sheldon Museum of Art, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, UNL-Gift of Lois Bowden. Via The Willem de Kooning Foundation.

The interior of Willem de Kooning’s Studio, Fourth Avenue, New York City, 1946. Photograph by Harry Bowden. Sheldon Museum of Art, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, UNL-Gift of Lois Bowden. Via The Willem de Kooning Foundation.

In 1958, Willem de Kooning moved into a loft on the top floor of 831, during one of his most creative periods, and remained there until he decamped from New York City entirely for East Hampton. It was while living here that de Kooning became an American citizen, and painted Rosy-Fingered Dawn at Louse Point, the first of his paintings acquired by a European museum, and Door to the River, which is now at the Whitney Museum of American Art. It was also here that in 1962 he was photographed by noted portraitist Dan Budnik. That image, “Willem de Kooning, 831 Broadway, New York,” is now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

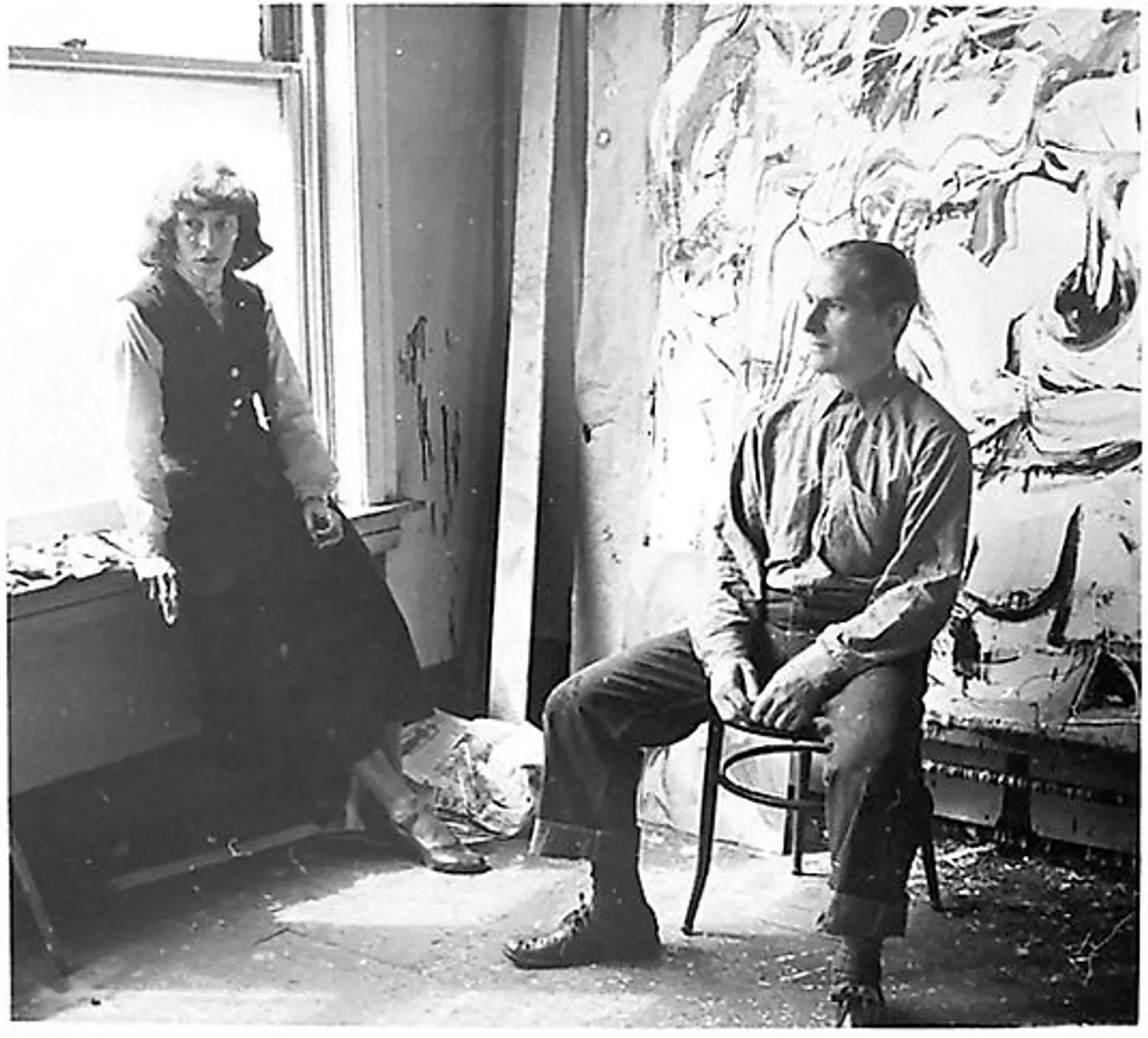

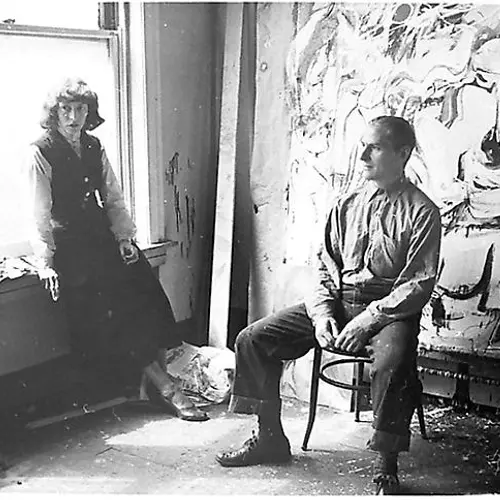

Willem and Elaine de Kooning with a state of Excavation in his Fourth Avenue studio, c. 1949. Photograph by Walter Auerbach. Via The Willem de Kooning Foundation.

Willem and Elaine de Kooning with a state of Excavation in his Fourth Avenue studio, c. 1949. Photograph by Walter Auerbach. Via The Willem de Kooning Foundation.

De Kooning and his fellow abstract expressionists shifted the center of the art world from New York to Paris after World War II, and much of that artistic ferment took place in and around 827-831 Broadway. Elaine de Kooning, artist, teacher and chronicler of the American art scene, had a studio on the third floor of 827. She was working there on a commission of John F. Kennedy’s official portrait for the Truman Library when he was killed in November 1963. In later years, the noted abstract expressionist painters Larry Poons and Paul Jenkins both also lived and worked in studios here. Jenkins moved into the building in 1963 and painted his celebrated work “Phenomena 831 Broadway” here.

William S. Rubin also resided at 831 in the late 1960s until 1974 when Larry and Paula Poons took over his loft. Rubin, Director of the Department of Painting and Sculpture at MoMA from 1973-1988, is credited with playing “a crucial role in defining the museum’s character, collections and exhibitions in the 1970s and 1980s,” according to the New York Times. His loft, which he hired a young Richard Meier to redesign, served as a showcase for his own considerable collection, as well as a meeting place for artists.

During the Poons’ long residence at 831, they continued the tradition of using the space as a gathering place for artists, especially during the ’70s and ’80s. Their long-time friend and Bob Dylan’s former road manager, Bob Neuwirth, held tryouts in their loft for the Dylan 1975-76 Rolling Thunder Review tour in the loft; in attendance, that night was Patti Smith and T-Bone Burnett.

If that were not enough, abstract expressionist artist Jules Olitski (1922-2007) made his home at 827 Broadway during the 1970s. Olitski was one of the leaders of the Color Field school of painting, an offshoot of Abstract Expressionism. This technique involved the color staining of canvases, rejecting brushwork popular with other abstract expressionists. During his lifetime, Olitski exhibited widely, including 150 one-man shows. In 1969 he became the third artist in history to have a one-man show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Howard Kaplan Antiques in 2009 via Samuel Globus/Flickr

Howard Kaplan Antiques in 2009 via Samuel Globus/Flickr

While this heady artistic brew was being mixed upstairs, downstairs Hollywood royalty went antique shopping. In the late 20th century the building was located in the heart of what became New York’s antique district. But Howard Kaplan Antiques, located here for 35 years, stood out as perhaps New York’s most prominent and sought-after antique dealership. Mr. Kaplan earned the sobriquet “antiques dealer to the stars” by cultivating patrons that included Faye Dunaway, Robert De Niro, Jacqueline Onassis, Woody Allen, Roone Aldridge, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, among many others.

But all this history was until quite recently slated to meet the wrecking ball, and still might. In August 2015, the buildings were acquired for $60 million by real estate investors Samson Klugman and Leo Tsimmer of Quality Capital and Caerus Group respectively. This corridor south of Union Square has recently become the epicenter of new tech-related development in New York, and Klugman and Tsimmer sought to cash in on the trend. When they filed plans to demolish the building and replace it with a 300-foot-tall retail and office tower, GVSHP submitted an emergency request to the Landmarks Preservation Commission to landmark the buildings. That request was denied, but GVSHP gathered more evidence of the buildings’ significance and support for their preservation from elected officials, art world luminaries, and hundreds of average New Yorkers. On Tuesday, the LPC voted unanimously to “calendar” the buildings, which means they are now officially under consideration for landmark designation, during which time they cannot be demolished or altered without the LPC’s approval. A hearing must take place within six months and a vote within a year, at which point we will know if this precious piece of New York history and architecture will live to tell another chapter in its remarkable story.

+++

This post comes from the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Since 1980, GVSHP has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid.

RELATED:

Interested in similar content?

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

“…shifted the center of the art world from New York to Paris after World War II….”

Really?