Giving citizens a (virtual) voice: How NYC can strengthen public input post-pandemic

Photo by Chris Montgomery on Unsplash

Nearly a year into the pandemic, decision-making in our cities has taken center stage. Locally grown proposals by council people, small business owners, and neighbors have proven the ability to cut through red tape and innovate quickly to solve problems. Outdoor dining structures and pedestrian-only streets were implemented at a rate thought impossible before. At the same time, top-down mandates about public safety and use of funds have been at best called into question, and at worst, completely fumbled. Slow action and political quibbles have left many critical decisions out of public hands.

In the face of many more important decisions to come about our city, it is high time to address a challenge that has plagued us long before the pandemic — the lack of substantial public input into big decisions.

I was intimately introduced to this problem in 2015, when I co-founded a pro bono project with Van Alen Institute associate director Stacey Anderson called the Tanks at Bushwick Inlet Park. The Tanks were a design proposal to adaptively reuse ten historic and decommissioned oil tanks on the Brooklyn waterfront and transform them into a public park. We ran wild reimagining what these tanks could become—greenhouses, art installations, oyster habitats, and most importantly, a symbol of rebirth and transformation to a new green world.

In our four years of advocacy, we attended dozens of community meetings. Big ones, little ones, long ones, and short ones. From the very first, we were astounded. At a gathering where decisions were being made that would impact the lives of hundreds or thousands of residents of all backgrounds and walks of life, those present numbered fewer than 30 and represented only a small sliver of the neighborhood demographic. The meetings often took place at 4PM or 5PM, when many were still at work. And when we tried to find information about how to attend or what would be discussed ahead of time, it took a labyrinthine digital quest to uncover it.

Even at meetings where attendance was slightly more encouraging, the flat PowerPoint presentations left us with more questions than answers and a feeling of dis-ease and disinformation.

This system is antiquated and dysfunctional. With the lack of outreach, awareness, and attendance, the status quo hurts our cities with a double whammy—those who show up might vote down potentially beneficial projects because they don’t understand them, and approve projects with unknown negative impacts because they aren’t made clear.

Perhaps this is the moment, with everything up in the air and on the table, to reimagine this longstanding barrier to progress in our cities.

In October 2020, the City of New York took a first step to move engagement online with NYC Engage, a digital portal where people can learn about and register to attend online public hearings. Although Zoom proved to be a blunt instrument for gatherings that require nuance, subtlety, and collaboration, it boosted attendance by the hundreds and welcomed a wider array of residents to join.

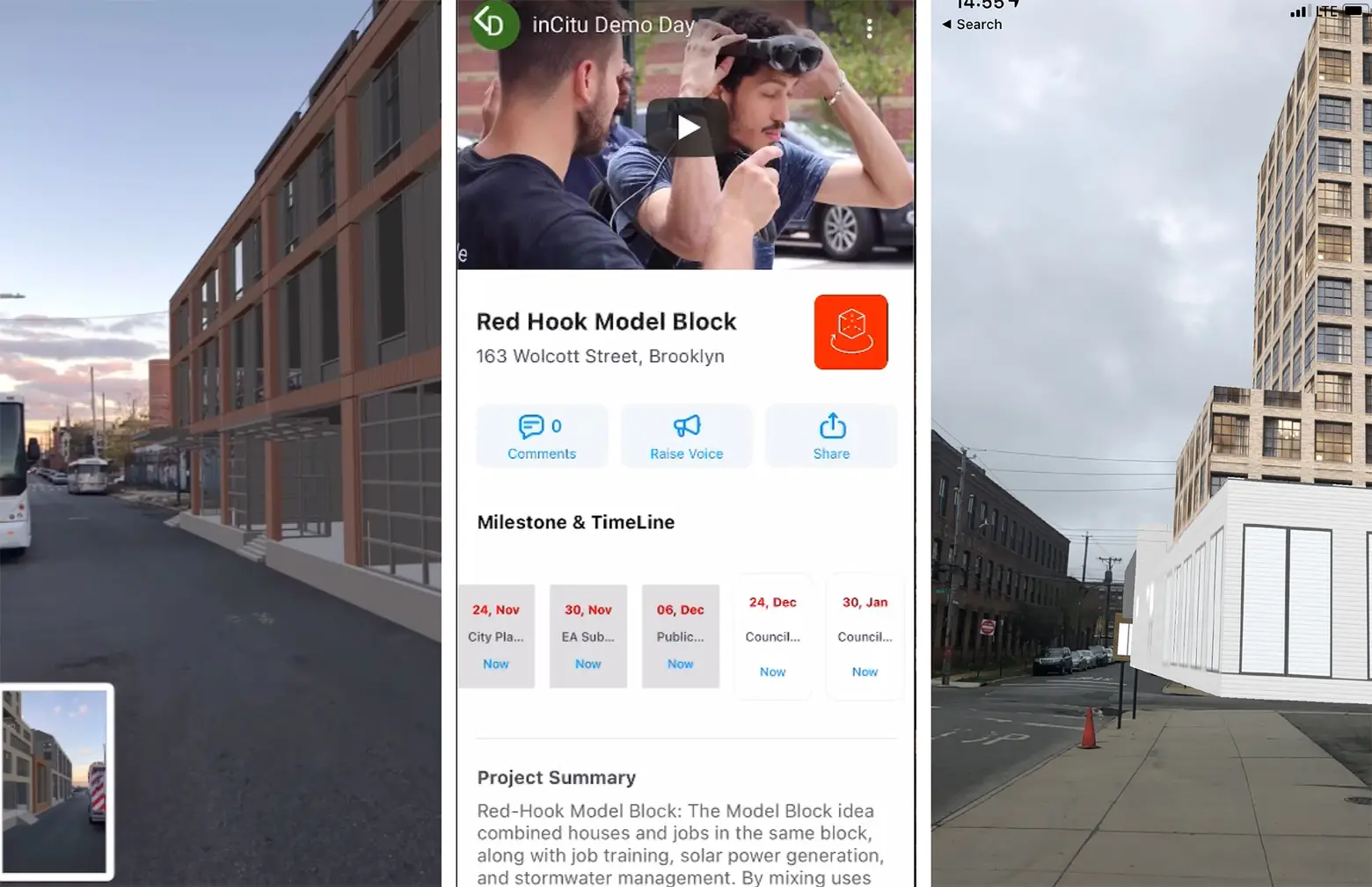

Screenshots from the inCitu app, courtesy of inCitu

Other New Yorkers, like Dana Chermesh-Reshef, are wielding technology for a more humane, empathetic result. A Brooklyn-based architect from Tel-Aviv and an Entrepreneur-in-Residence at Schmidt Futures, Chermesh-Reshef is the founder of inCitu, a digital tool she hopes will transform how people learn about, understand, and give feedback on projects in their neighborhood.

Using augmented reality, inCitu shows community members what a project will actually look like on their street. Viewers can take their device to the site in question, download the app, and lift the screen up to see a visualization of the proposed project. This allows them to understand impacts in three-dimensions; light, air, and parking implications, visual disturbances, and how the project relates in scale and aesthetic to the rest of the neighborhood. They can also see where the entrances are relative to transit and bike lanes.

Chermesh-Reshef believes “people don’t care about birds-eye views and aerial maps. They care about how many cars are parked on their street at 8AM, whether it’s safe for their children, if there is a big shadow cast on their park.” She hopes that if inCitu is successful, “it will make people more comfortable with change.” The app allows citizens to explore and give feedback on a project at their own convenience and with a lot more information.

“60 or 100 years ago, Robert Moses’ top-down approach was the prevalent way to get big projects done,” said Chermesh-Reshef. “Today, technology can allow many people to become the Jane Jacobs of their own neighborhoods. We can crowdsource community input very effectively.”

The first version of this app was already implemented successfully in Red Hook, where inCitu partnered with Geopogo and Magic Leap to demonstrate a proposed rezoning of a “model block,” or a mixed-use block that combined housing and job creation. Just by standing on their street corner and putting on a set of AR goggles, Red Hook residents explored in augmented reality three possible scenarios of the rezoning.

Since then, the concept has spread beyond its Brooklyn borders; several cities will pilot the app this Spring to communicate the impacts of development projects, sea-level rise, and zoning code changes. In response to COVID, one city wants to use the app to find underutilized spaces that can be made into social-distanced schooling.

Across the country, other leaders see the opportunity presented by this global upset. Evan Lowry, geographer and city planner for the City of Charlotte, NC, explained how their municipality responded to the pandemic on Sidewalk Labs’ City of the Future podcast. They gave up their in-person meetings in exchange for a website that allows community members to give feedback online. Lowry is also building an online visualization tool to show citizens what their streets could look like in 20 years.

“It’s a game-changer for the residents,” says Lowry. “If they can pull up a website and turn a layer off and on and see how it relates to their own house or their own neighborhood… [they] would be able to make [their] own assumptions.”

If nothing else, the past year has left us rethinking the status quo of every aspect of the civic realm. It has catalyzed us to raise our voices and be heard. We are asking ourselves and our leaders: Why does it have to be like this? Could things be better?

Perhaps we can leverage our newfound acceptance of change towards building better cities for us all.

+++