Going nuclear: The Manhattan Project in Manhattan

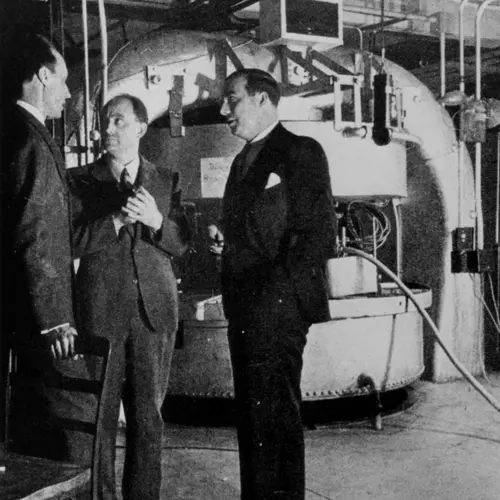

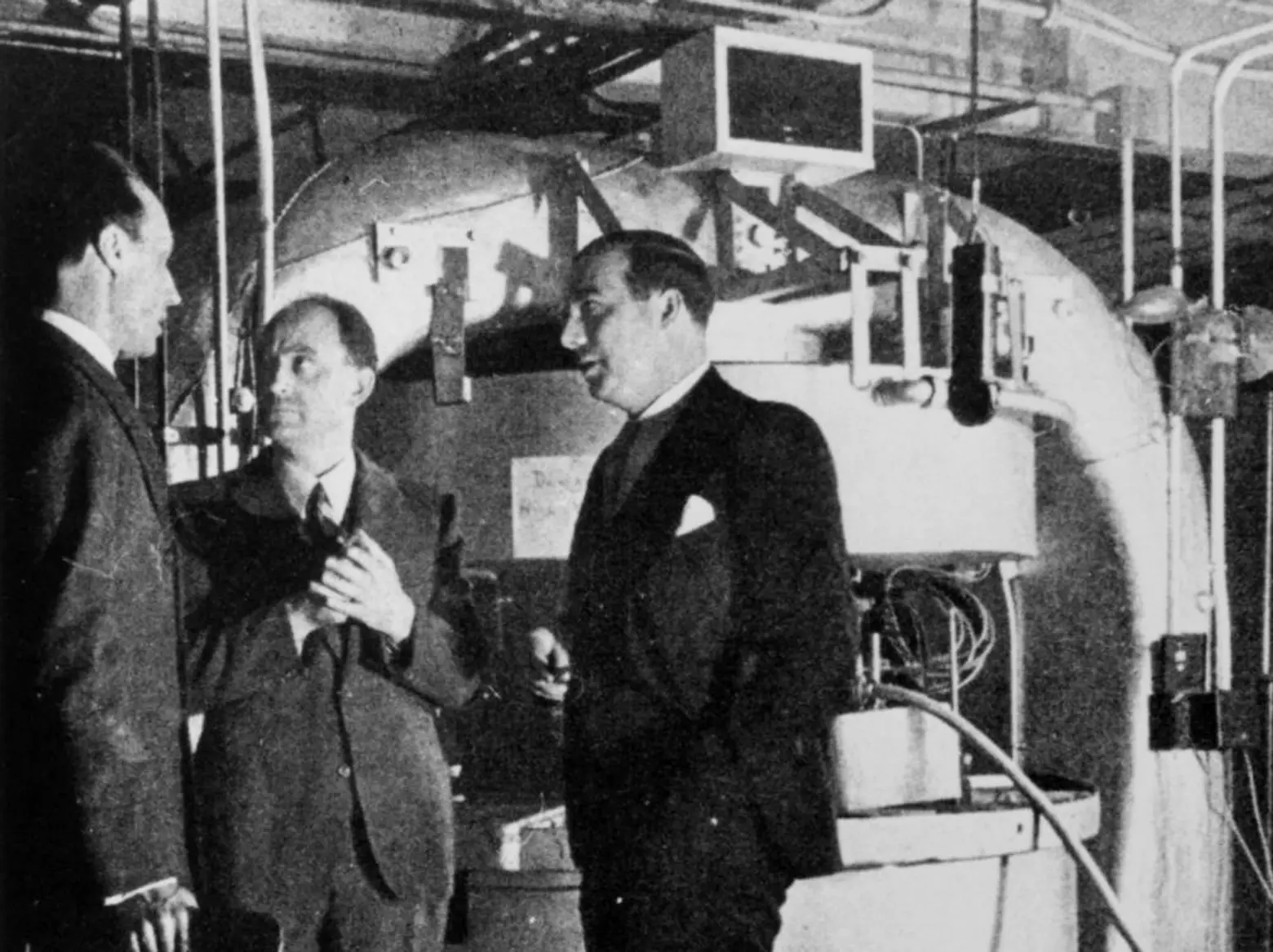

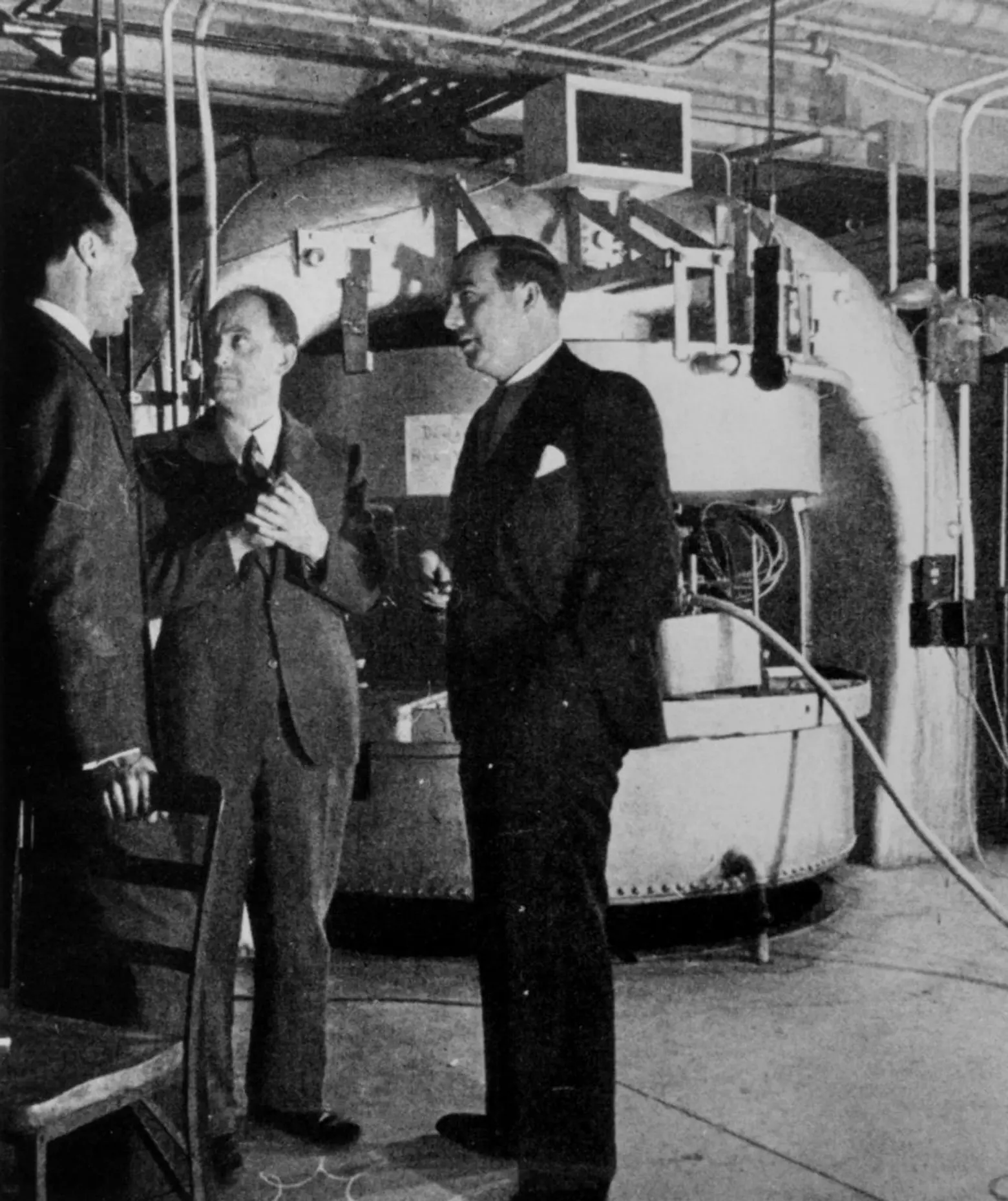

A 1939 photo of an atom-smasher (cyclotron) at Columbia University. Via Wiki Commons.

Most people assume that “The Manhattan Project” is a clever codename, a misnomer for the famous test sites in New Mexico. But, with over 1,200 tons on uranium stashed on Staten Island, and a nuclear reactor whizzing away at Columbia University, the top-secret wartime program began in Manhattan, and fanned out across the island, from its southern tip to its northern reaches, from its dimmest docks to its brightest towers. Ultimately 5,000 people poured into New York to work on the project, so duck, cover and get ready for an atomic tale of scientists, soldiers, and spies.

270 Broadway, via Wiki Commons

270 Broadway, via Wiki Commons

When Franklin Roosevelt established the Office of Scientific Research and Development, by Executive Order, in 1941, he placed the nation’s nascent nuclear program under the auspices of the Army Corps of Engineers. The program kicked off in June 1942, on the 18th floor of 270 Broadway, home to the Engineers’ North Atlantic Division. Thus was born The Manhattan Engineer District, better known as the Manhattan Project. Eventually, the offices at 270 Broadway would not only run atomic research but also preside over the creation of entire nuclear cities in Tennessee, New Mexico, and Washington State.

Pupin Hall, via Wiki Commons

Pupin Hall, via Wiki Commons

It was no coincidence that the Army headquartered the project on Broadway. Further north on the avenue, at 120th Street, in the basement of Columbia University’s Pupin Hall, John Dunning, and Enrico Fermi had conducted the first nuclear fission experiment in the United States.

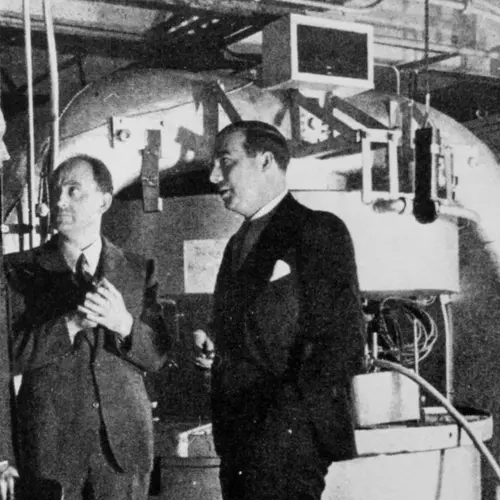

The cyclotron built by Dunning in 1939 in the basement of Columbia’s Pupin Hall. Dunning is on the left with Enrico Fermi in the center and Dana P. Mitchell on the right. Via Wiki Commons.

The cyclotron built by Dunning in 1939 in the basement of Columbia’s Pupin Hall. Dunning is on the left with Enrico Fermi in the center and Dana P. Mitchell on the right. Via Wiki Commons.

The fission experiments at Columbia on January 25, 1939, confirmed the findings of German chemists Otto Hahn, Lise Meitner and Fritz Strassmann, who had discovered nuclear fission weeks earlier. But at Columbia, Dunning realized the practical applications of nuclear fission. He wrote on January 25th, “Believe we have observed new phenomenon of far-reaching consequences…here is real Atomic Energy.” Those consequences were the possibility of an uncontrolled chain reaction, and the creation of the Atomic Bomb. He noted two days later that he and his colleagues, “agreed to keep [their findings] rigorously quiet in view of serious implications of atomic energy release internationally.”

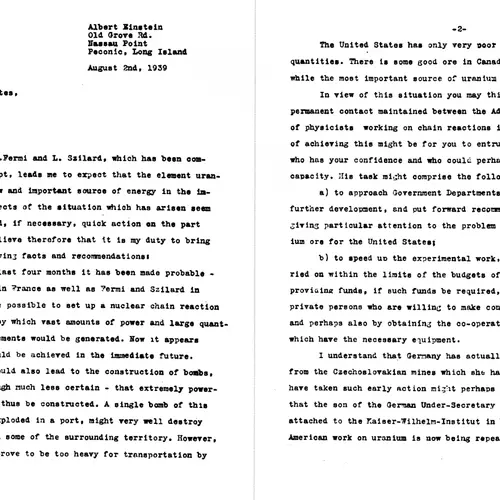

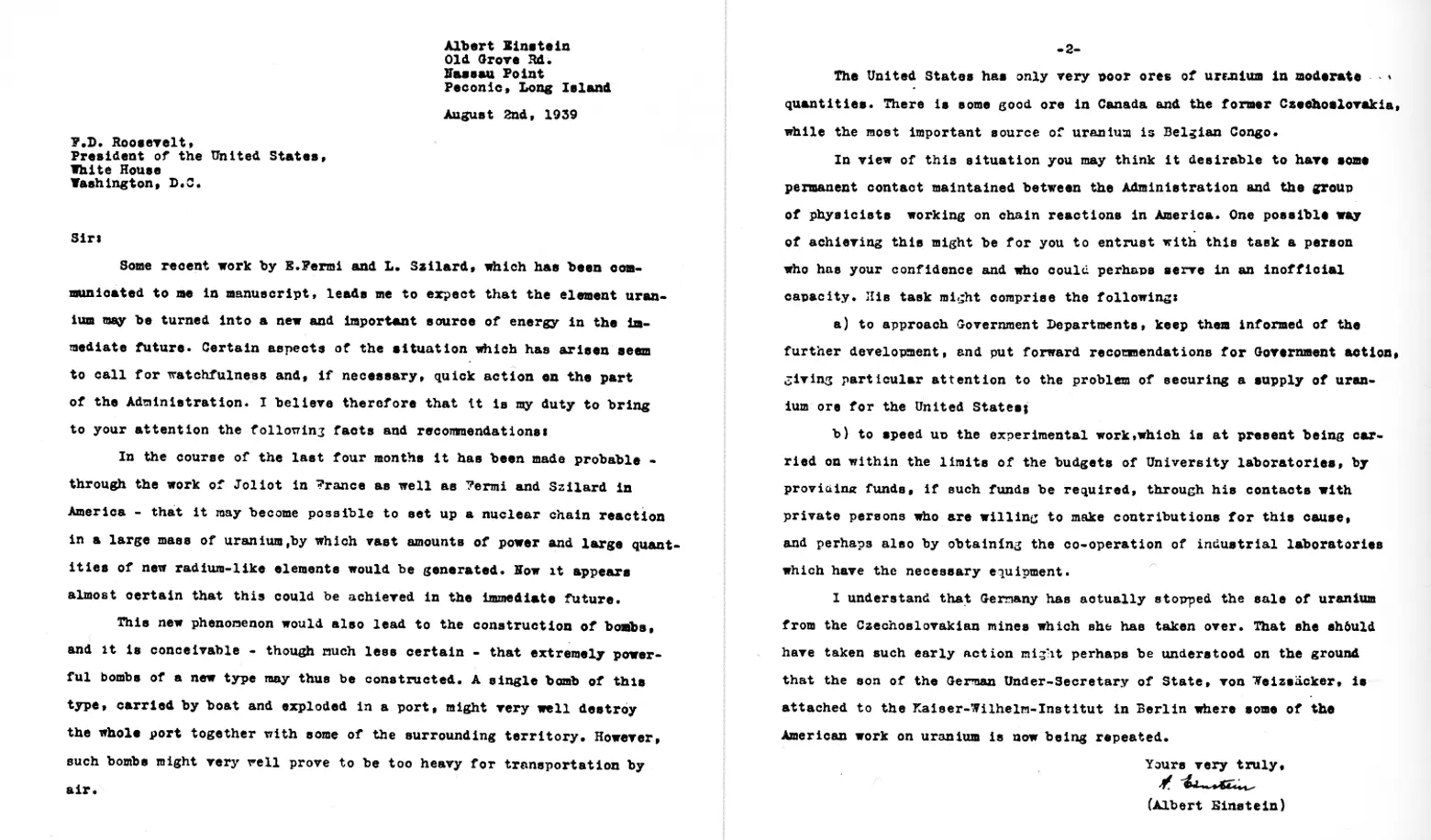

Einstein’s letter to FDR, via Wiki Commons

Einstein’s letter to FDR, via Wiki Commons

Well, they did tell someone. The Columbia scientists, led by Leo Szilard, sent a letter to FDR, dated August 2nd 1939, and signed by Albert Einstein, explaining that “the element uranium may be turned into a new and important source of energy in the immediate future,” and that “this new phenomenon would also lead to the construction of…extremely powerful bombs of a new type.” Lest the Germans produce the bomb first, the scientists warned, the administration should “speed up the experimental work” on uranium already being carried out at Columbia.

With the support of the Federal Government now assured, Columbia University became chiefly responsible for the K-25 Gaseous Diffusion research program as early as 1941. By 1943, the University’s facilities were converted wholesale into the Manhattan Project’s Substitute Alloy Materials (SAM) Laboratories, with additional space in the Nash building at 3280 Broadway.

The Columbia scientists noted that the world’s “most important source of Uranium is Belgian Congo.” Lucky for the K-25 team, stockpiles of Congolese uranium had been sitting, undetected, on Staten Island since 1940.

Following the fall of Belgium, Edgar Sengier, a Belgian mining executive, knew he had to keep the ore away from the Axis. In a swift and decisive move, he surreptitiously shipped over 1,200 tons of uranium – half the supply available in Africa – to Staten Island. He himself then decamped to New York and took up offices in the Cunard Building, at 25 Broadway, just waiting for the right buyer. When the Army Corps of Engineers came knocking, he sold his stock for a song, doling out uranium for a dollar a pound.

With a heady supply of Sengier’s top grade ore, work at the Columbia SAM Lab reached its peak in September 1944, employing 1,063 people, including Atomic Spies. Klaus Fuchs, Codenamed “Rest,” “Charles” and “Bras” passed along nuclear intelligence so valuable to Soviets that the Atomic Heritage Foundation holds the USSR was able to develop and test an Atomic Bomb nearly two years earlier than otherwise expected. Fuchs arrived at Columbia in 1943 and would make his mark at either end of Broadway before moving on to Los Alamos in 1944.

Not only did Fuchs pass information from the SAM Lab to his Russian counterparts, but also the Socialist scientist infiltrated the Woolworth Building, New York’s “Cathedral of Commerce.” Floors 11-14 of Cass Gilbert’s neo-Gothic masterpiece housed the Tellex Corporation, a subsidiary of the chemical engineering contractor W.M. Kellogg, which outfitted Columbia’s Nash building, then built K-25 facilities at the Clinton Engineer Works, in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. From inside the sweeping Woolworth tower, the science behind uranium enrichment made its way to Moscow.

The historian Richard Rhodes calls Klaus Fuchs the “most productive” Soviet spy on the Anglo-American atomic bomb, and the physicist Has Bethe, head of the Theoretical Division at Los Alamos, said Fuchs was the only physicist he knew who truly changed history. That would have been true even if his intelligence was useless because his arrest in 1950 led to the conviction of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.

This brings us the era’s most famous Atomic Spies, who were both “guilty and framed.” As an engineer in the Army Signal Corps, Julius Rosenberg became a Soviet spy on Labor Day, 1942. While he is most famous for recruiting his brother-in-law, David Greenglass, to pass along atomic secrets from Los Alamos, Rosenberg himself spent a frenetic weekend in New York, copying secret Air Force documents from a Columbia safe, which he subsequently slipped to Soviet agents on the LIRR.

A swift hand-off this might have been, but Julius Rosenberg was by no means the most dexterous atomic spy in New York. That honor goes to Moe Berg, the major league catcher, linguist, lawyer and spy who (naturally) was deemed the United States’ best hope against Nazi nuclear warheads. In addition to playing 17 years in the majors, Berg, a native New Yorker, also spoke 12 languages, graduated magna cum laude from Princeton, studied at the Sorbonne, and earned a law degree from Columbia. His innate brilliance and facility with languages made him the perfect candidate to undertake an international assessment of the Nazi nuclear program.

That mission, codenamed “Project Larson” took him first to Italy to interview Axis scientists, then to Zurich where he came face to face with Werner Heisenberg, the Reich’s finest scientific mind. Berg had his orders: If it seemed the Germans were making headway on the bomb, Berg must shoot to kill. Berg concluded, correctly, that he needn’t waste the bullet; the Nazis had no bomb.

In short, Heisenberg wasn’t Oppenheimer. Before he became “the father of the Atomic Bomb,” as the head of The Los Alamos Laboratory, J. Robert Oppenheimer was a New Yorker. He grew up at 155 Riverside Drive, and attended the Ethical Culture Fieldston School on Central Park West. That humanistic outlook shaped his worldview, his work and his scholarship for the rest of his life. On July 16, 1945, upon witnessing the Trinity Test, the world’s first nuclear explosion, he thought of the Bhagavad Gita, translating verse XI,32 from the Sanskrit, as “I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

The Shinran Statue on Riverside Drive, via Claire Meyer/Flickr

The Shinran Statue on Riverside Drive, via Claire Meyer/Flickr

Oppenheimer became a lifelong advocate of nuclear control and disarmament, deeply aware of the catastrophic power of the weapon he had built. Interestingly, a survivor of the bomb’s destructive force stands on the same street as Oppenheimer’s boyhood home. On Riverside Drive, in front of the New York Buddhist Church between 105th and 106th streets, stands the statue of a 13th-century monk, Shinran Shonin, who survived the bombing of Hiroshima. The statue was brought to New York in 1955. Accordingly, both the origins of the Manhattan Project and the legacy of its power are at home in New York.

+++

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.