Harsenville to Carmansville: The Lost Villages of the Upper West Side

Via NYPL

In the 18th century, Bloomingdale Road (today’s Broadway) connected the Upper West Side with the rest of the city. Unlike lower Manhattan, this area was still natural, with fertile soil and rolling landscapes, and before long, countryside villages began sprouting along the Hudson River. They were a combination of farms and grand estates and each functioned independently with their own schools and roads.

6sqft has uncovered the history of the five most prominent of these villages–Harsenville, Strycker’s Bay, Bloomingdale Village, Manhattanville, and Carmansville. Though markers of their names remain here and there, the original functions and settings of these quaint settlements have been long lost.

HARSENVILLE

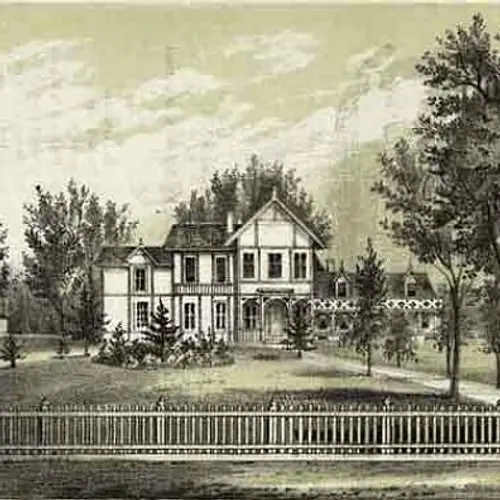

The Harsen house in 1888, via New-York Historical Society

The Harsen house in 1888, via New-York Historical Society

Harsenville ran from 68th Street to 81st Street, between Central Park West and the Hudson River. It began in 1701 when Cornelius Dyckman bought a 94-acre farm at Broadway and 73rd Street. His daughter Cornelia then married a farmer named Jacob Harsen, and they built their homestead at Tenth Avenue and 70th Street in 1763. Other farming families began to follow suit, setting up what became a small village, complete with schools, churches, and shops. At its height, it had 500 residents and 60 buildings, thanks largely to the perfect-for-tobacco soil and waterfront views. Harsenville Road was the main street, and it ran through present-day Central Park.

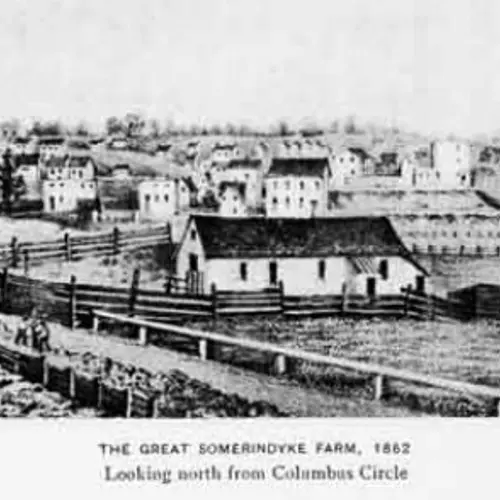

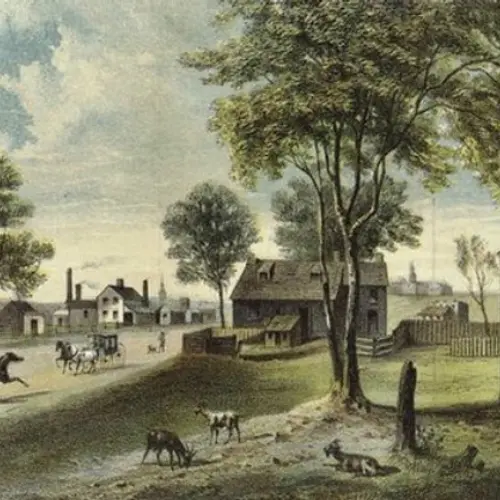

Somarindyck Farm at 75th Street

Somarindyck Farm at 75th Street

Somarindyck house at 77th Street

Somarindyck house at 77th Street

The Somarindyck family, another great farming clan, took up residence next to the Harsens on land from Columbus Circle to the 70s. Their home stood at Broadway and 75th Street, and it’s believed that Prince Louis Philippe lived here while exiled from France. They also had a second home at 77th Street, which was purchased in the late 1840s by Fernando Wood, who lived there while he served as NYC Mayor.

By the 1870s, the Harsen family began selling their land when farming fell out of fashion. In 1893, the Harsen home was torn down, and by 1911, Harsenville was no more, as brownstones and grand apartment houses began to dot the Upper West Side. There is one remnant of the village, however. The condo building at 72nd Street is named Harsen House.

STRYCKER’S BAY

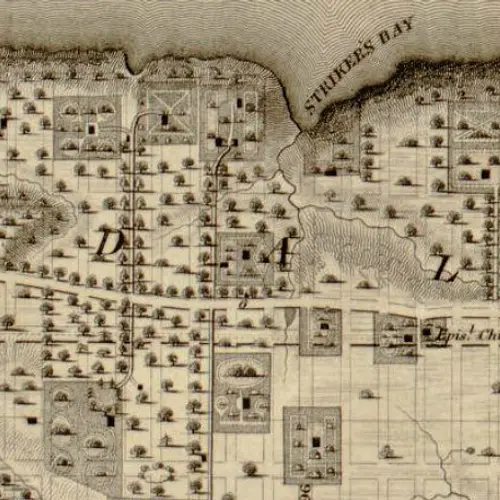

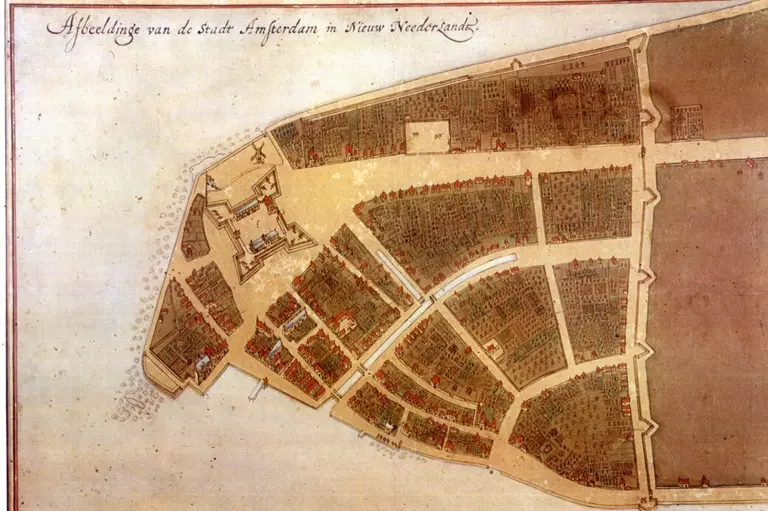

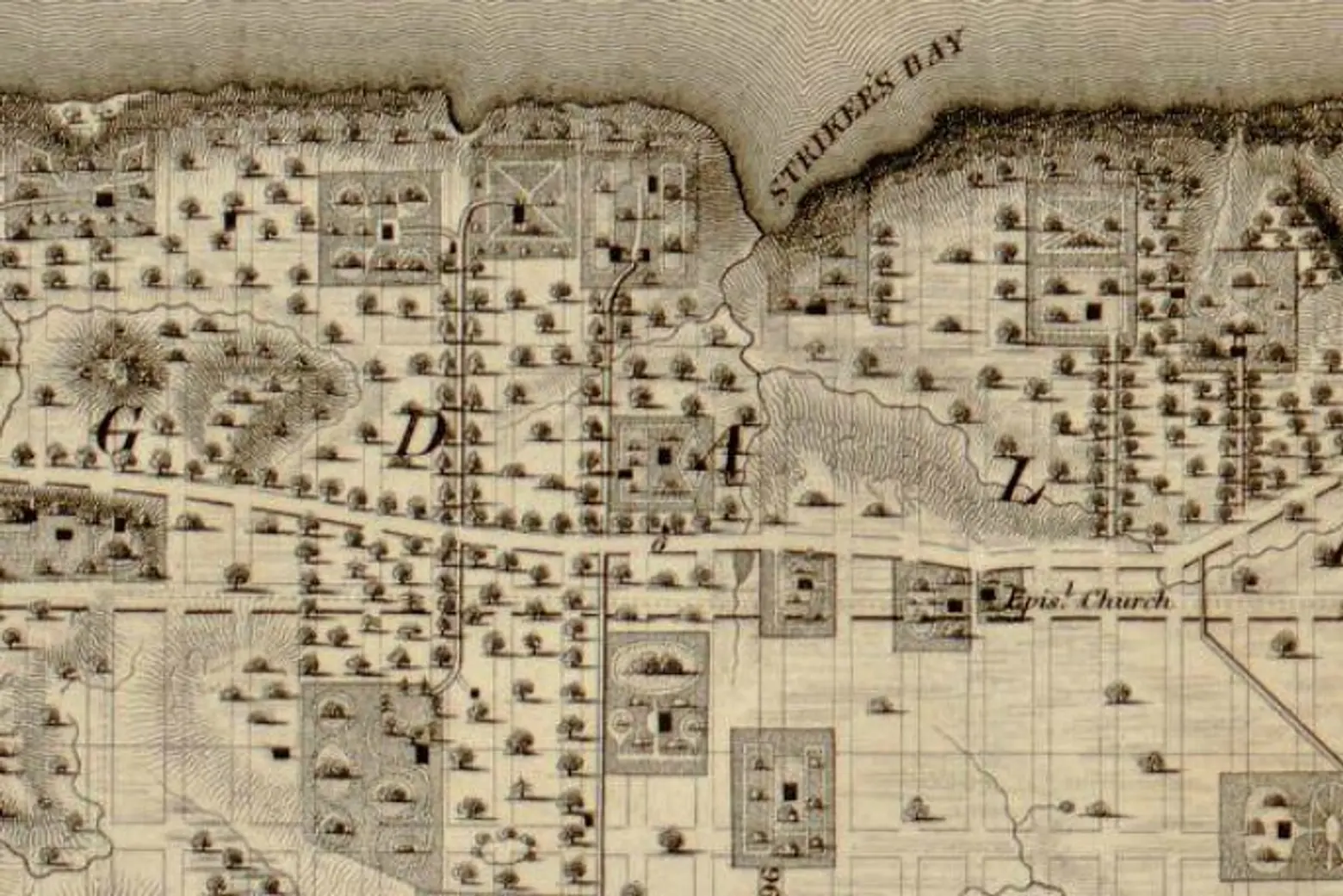

Strycker’s Bay maps via the Strycker’s Bay Neighborhood Council

From 86th to 96th Streets was the village of Strycker’s Bay, situated atop an elevated piece of land next to an inlet. The name came from Gerrit Striker, who built his farm at Columbus Avenue and 97th Street. At the southern end, John McVickar had a 60-acre estate at 86th Street, where his grand Palladian house stood. The enclave was a wealthy suburb, made possible by a ferry that took residents downtown. Striker’s farmhouse eventually became the Striker’s Bay Tavern in the late 19th century. It featured a lawn along the river, dance floor, and shooting targets.

Today the name lives on with the Strycker’s Bay Neighborhood Council, a group that supports affordable housing on the Upper West Side, as well as the Strycker’s Bay Apartments on 94th Street.

BLOOMINGDALE VILLAGE

North of Strycker’s Bay was Bloomingdale Village, which stretched between 96th and 110th Streets. The Dutch brought the name with them in the 1600s, as “Bloemendaal,” which translates to “valley of flowers.” The Bloomgindale District originally encompassed the entire west side from 23rd Street to 125th Street, made up of the farms and villages along Bloomingdale Road. But in 1820, this particular area got its moniker when the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum opened on what is today the Columbia University campus.

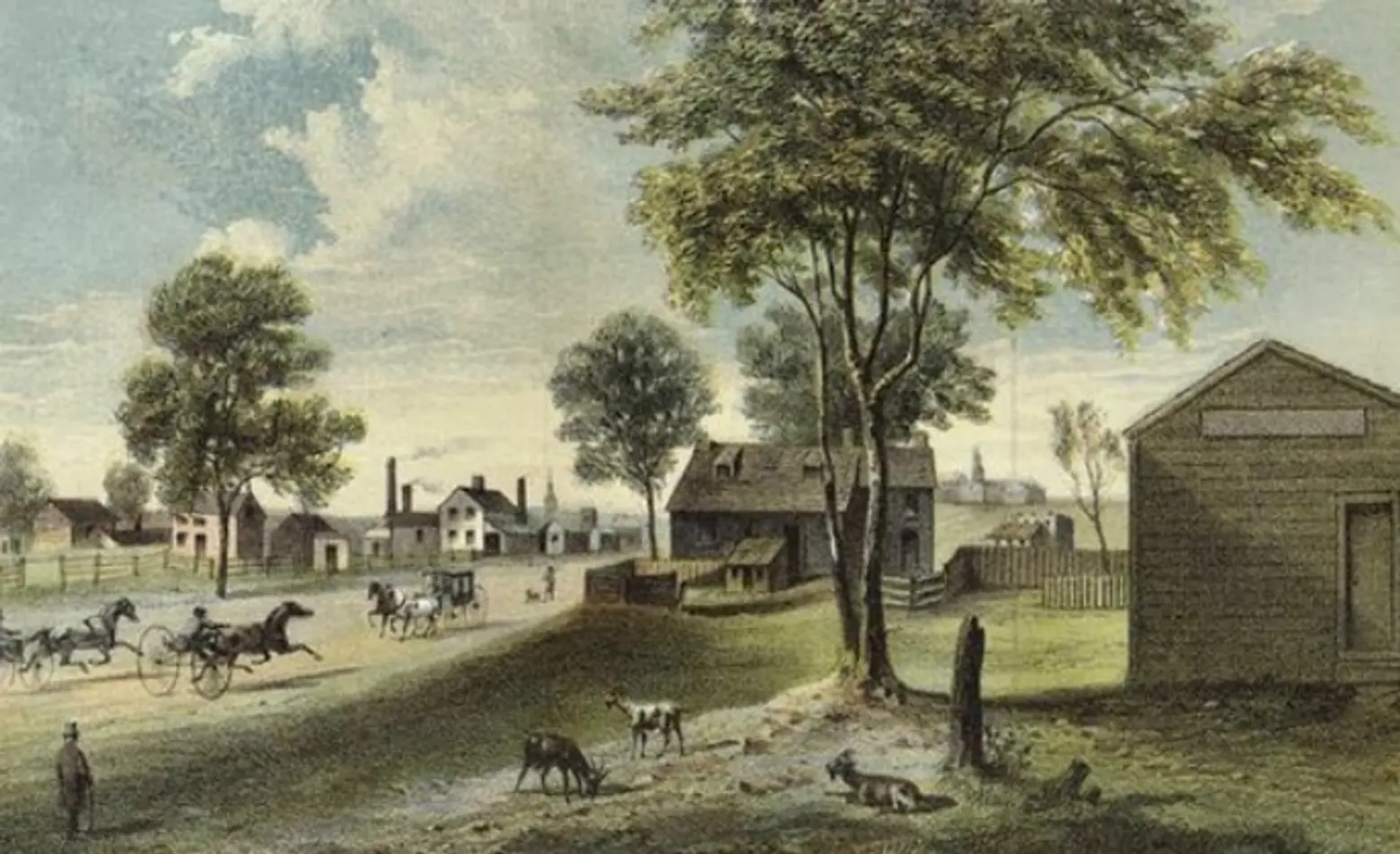

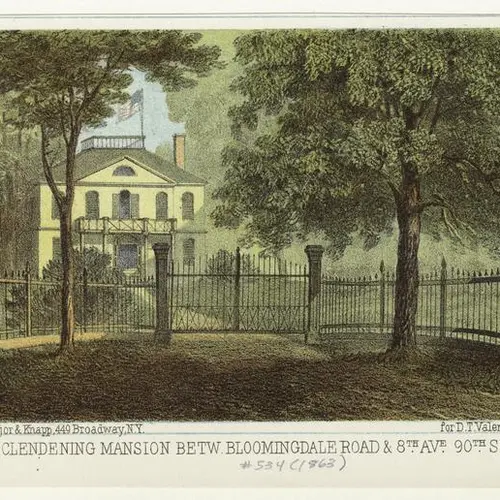

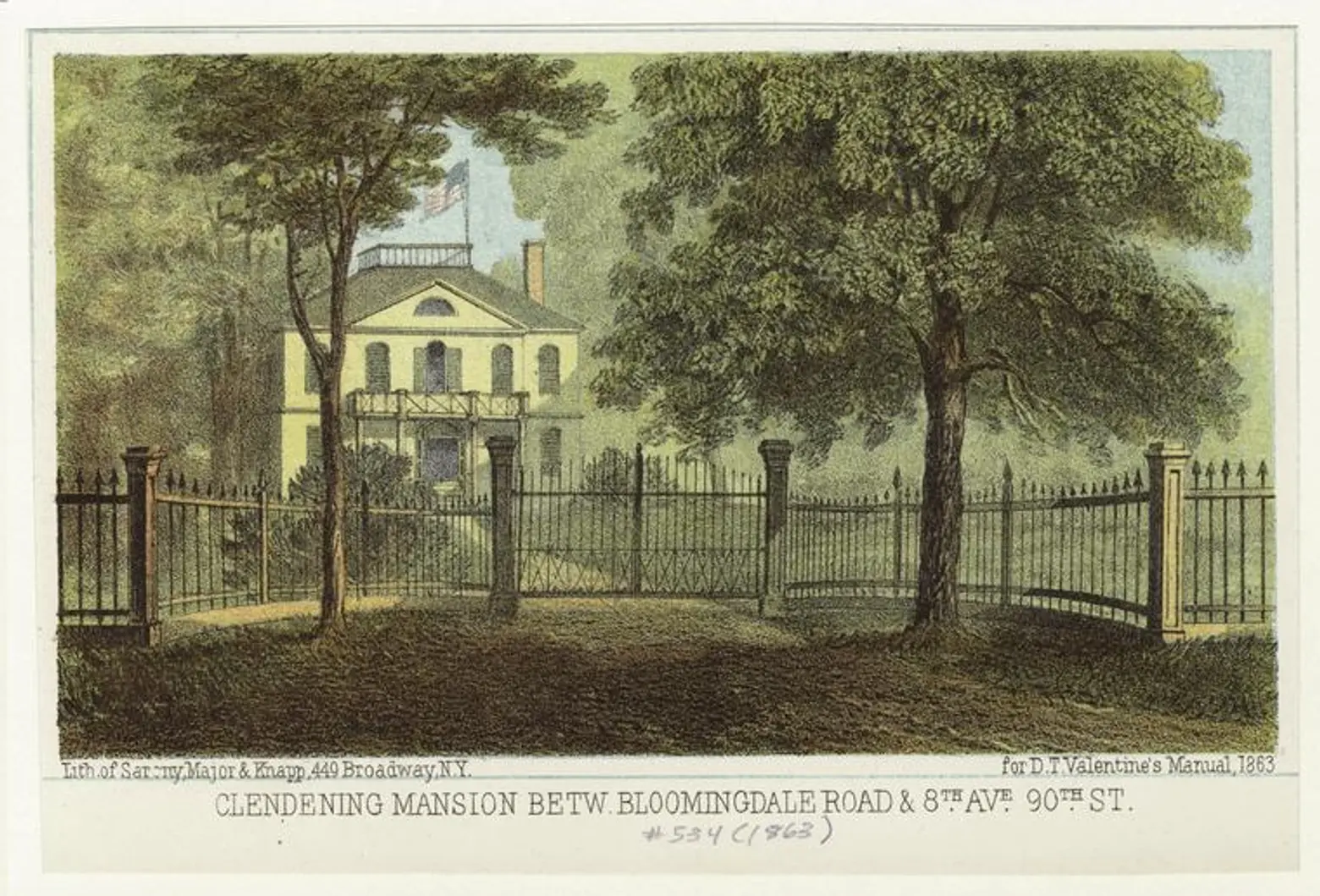

The Clendening mansion, depicted in an 1863 edition of Valentine’s Manual

The Clendening mansion, depicted in an 1863 edition of Valentine’s Manual

The physical outline of the village is defined by a natural depression in the land (hence why it’s today called Manhattan Valley), and in the 1800s, most of it was occupied by the farm of wealthy merchant John Clendening. His land ran from Bloomingdale Road to Eight Avenue, between 99th and 105th Streets. At Amsterdam Avenue and 104th Street was his personal mansion, so within Bloomingdale Village the area became known as Clendening Valley.

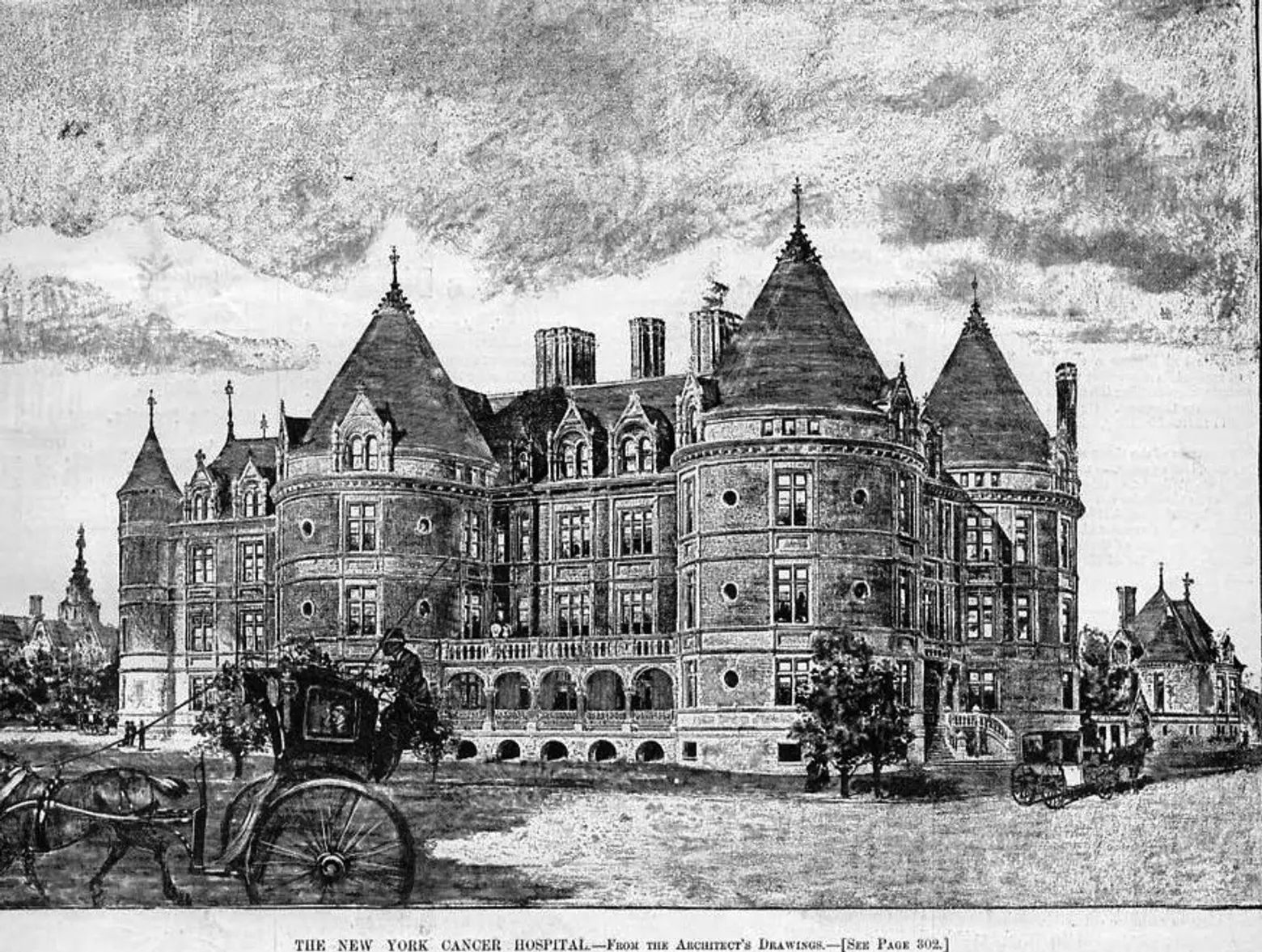

The Village began to change course in the mid 1800s when the Croton Aqueduct was constructed above the valley. Later in the century, large institutions—the Hebrew Home for the Aged, the Catholic Old Age Home, and the New York Cancer Hospital, to name a few—were erected in the area. It was thought that their location resembled the bucolic countryside, and would therefore attract wealthy patients and patrons. In 1904, Bloomingdale Village’s fate was sealed when Columbia University purchased the insane asylum building and the IRT – Seventh Avenue subway opened.

MANHATTANVILLE

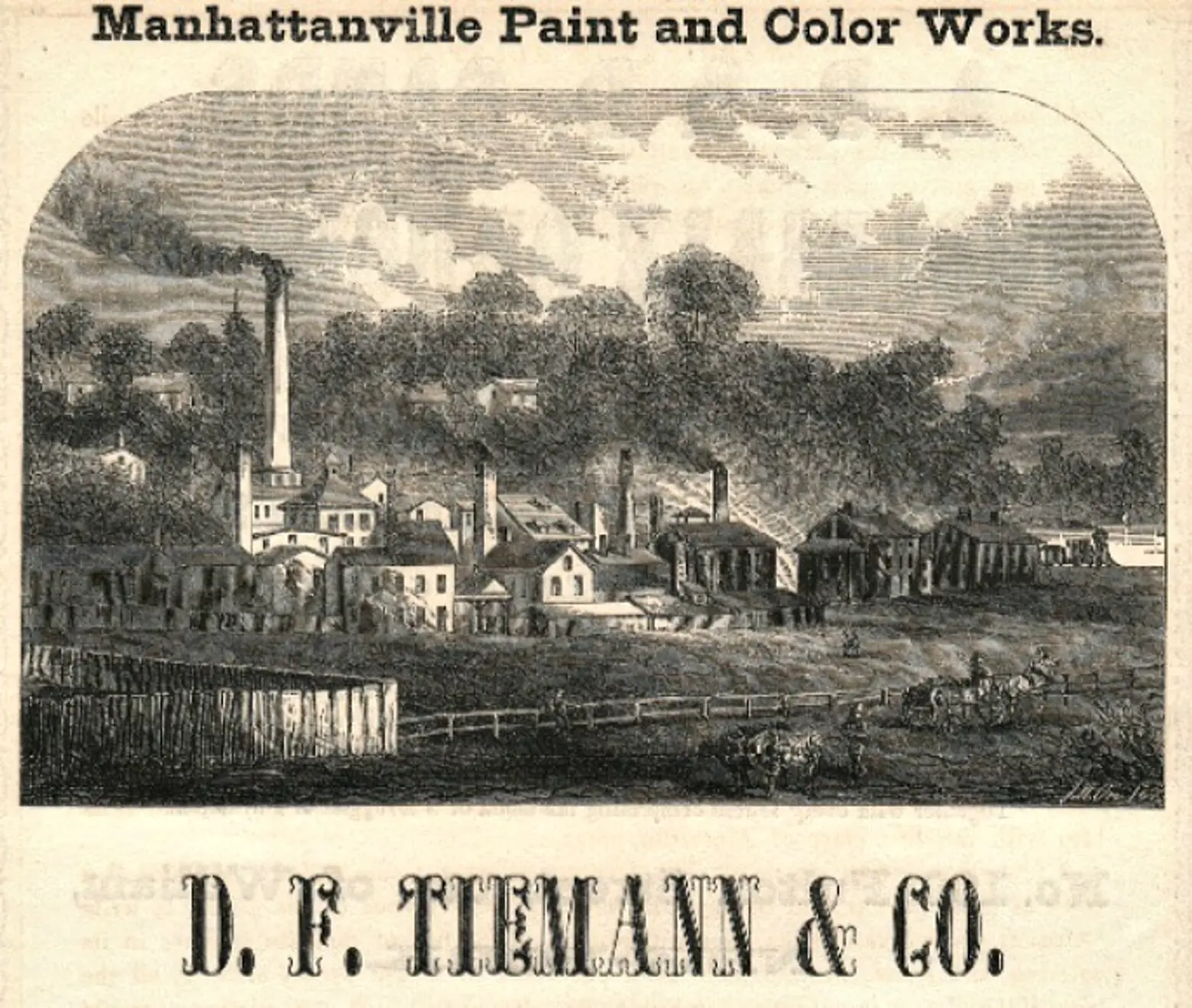

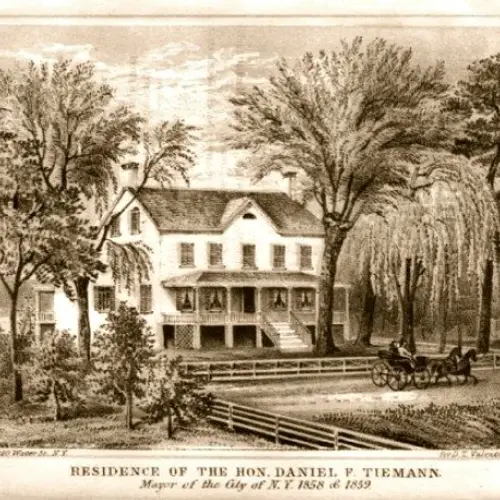

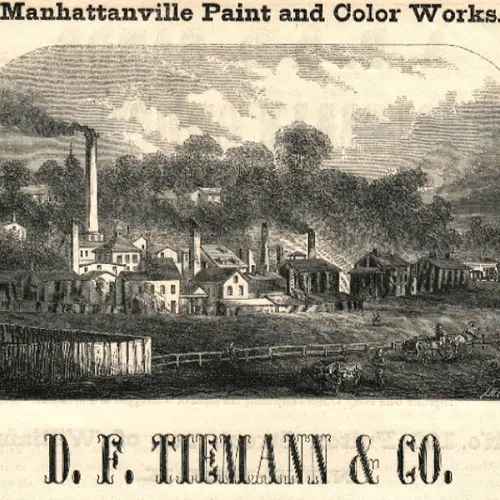

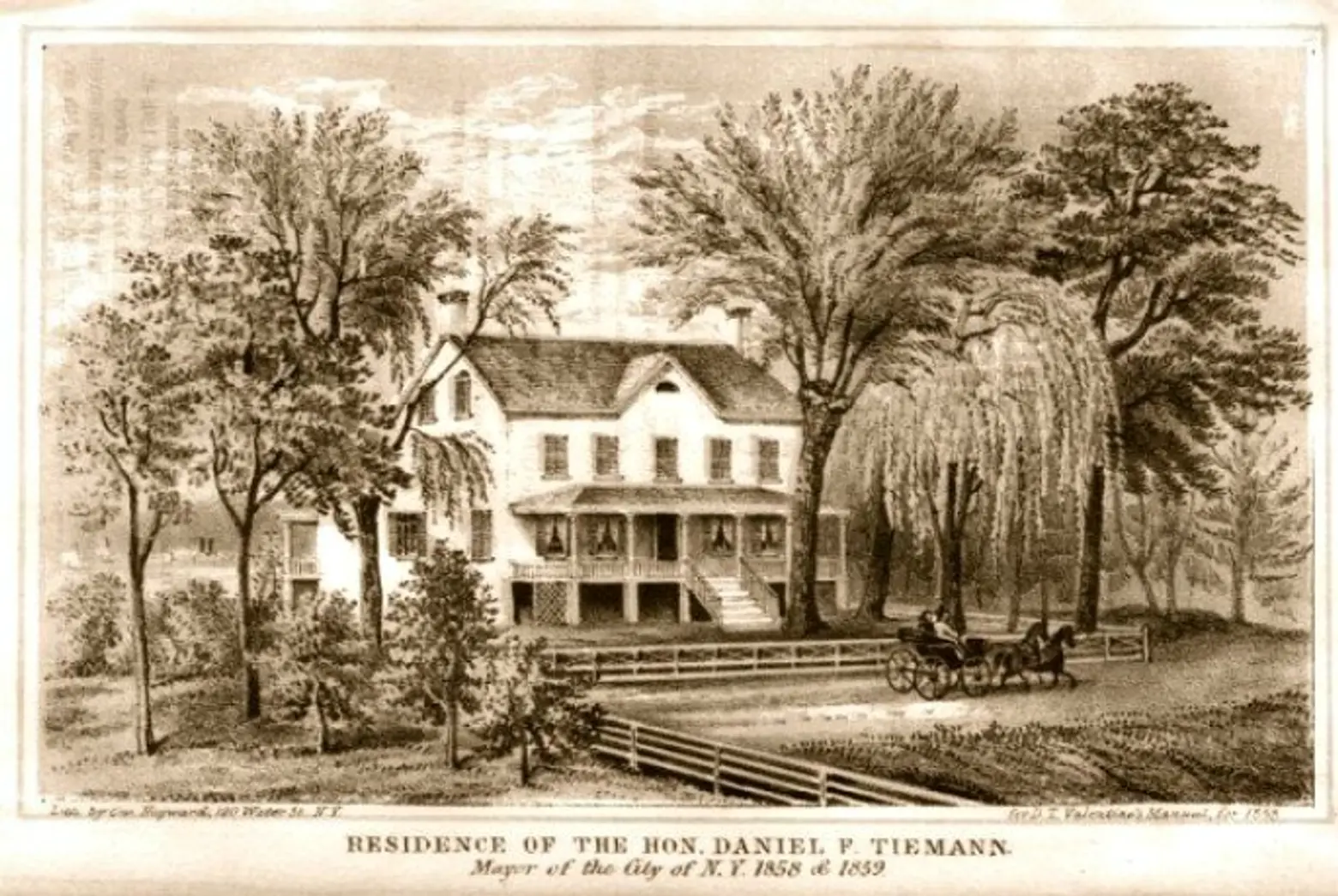

Tiemann Estate depicted in an 1858 edition of Valentine’s Manual

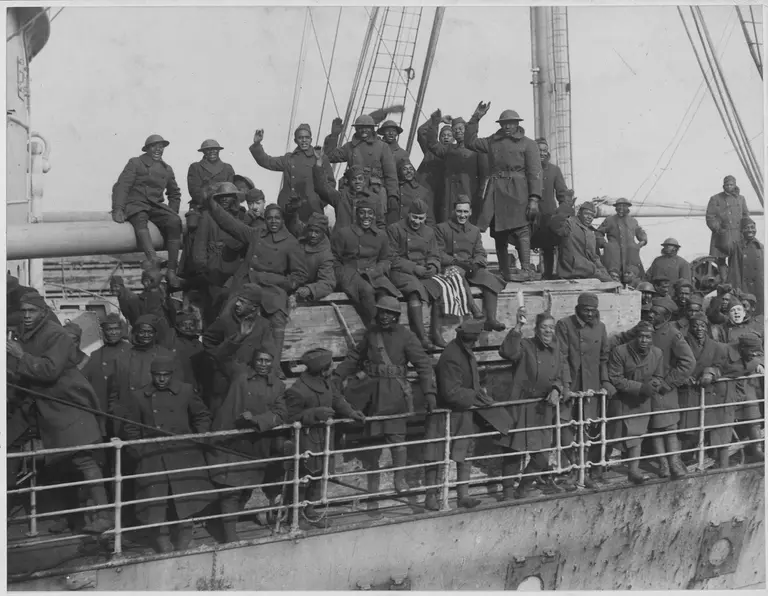

Manhattanville was perhaps the most bustling of the West Side villages. It also sat within a valley, this one running roughly from 122nd to 134th Streets. It was officially incorporated as a village in 1806, thanks to its commercial waterfront, warehouses, and factories, as well as the fact that it had a rail station and ferry terminal. The area was laid out by wealthy Quaker merchants who owned nearby country homes.

One of Manhattanville’s most prominent residents was Daniel F. Tiemann, who owned D.F. Tiemann & Company Color Works, a paint and pigment manufacturer. The factory had originally been located in Gramercy, but moved uptown in 1832 when a fresh water spring was discovered. Tiemann would go on to become a founding trustee of Cooper Union and mayor of NYC from 1858 to 1860. In addition to wealthy industrialists like Tiemann, the neighborhood was made up of a mix of poor laborers, tradesmen, slave owners, and British loyalists. After the Civil War, Jewish immigrants moved into the area.

In 1847, the Academy of Convent of the Sacred Heart, which would become Manhattanville College, moved just atop the hill of the village, and in 1853 the Catholic Christian Brothers moved their school from Canal Street to 131st Street and Broadway, establishing Manhattan College. Unlike Bloomingdale Village, Manhattanville didn’t change when the IRT subway opened in the early 1900s, as it only enhanced the area’s industrial and commercial nature. However, after the stock market crash of 1929, the neighborhood lost its manufacturing base and jobs and residents began to move to Harlem proper and elsewhere in the city. Today, Manhattanville is best known for being the site of Columbia University’s controversial expansion plan.

CARMANSVILLE

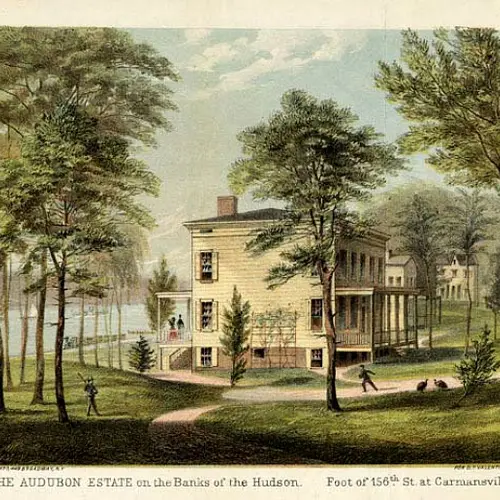

Audobon’s estate depicted in an 1864 edition of Valentine’s Manual

Audobon’s estate depicted in an 1864 edition of Valentine’s Manual

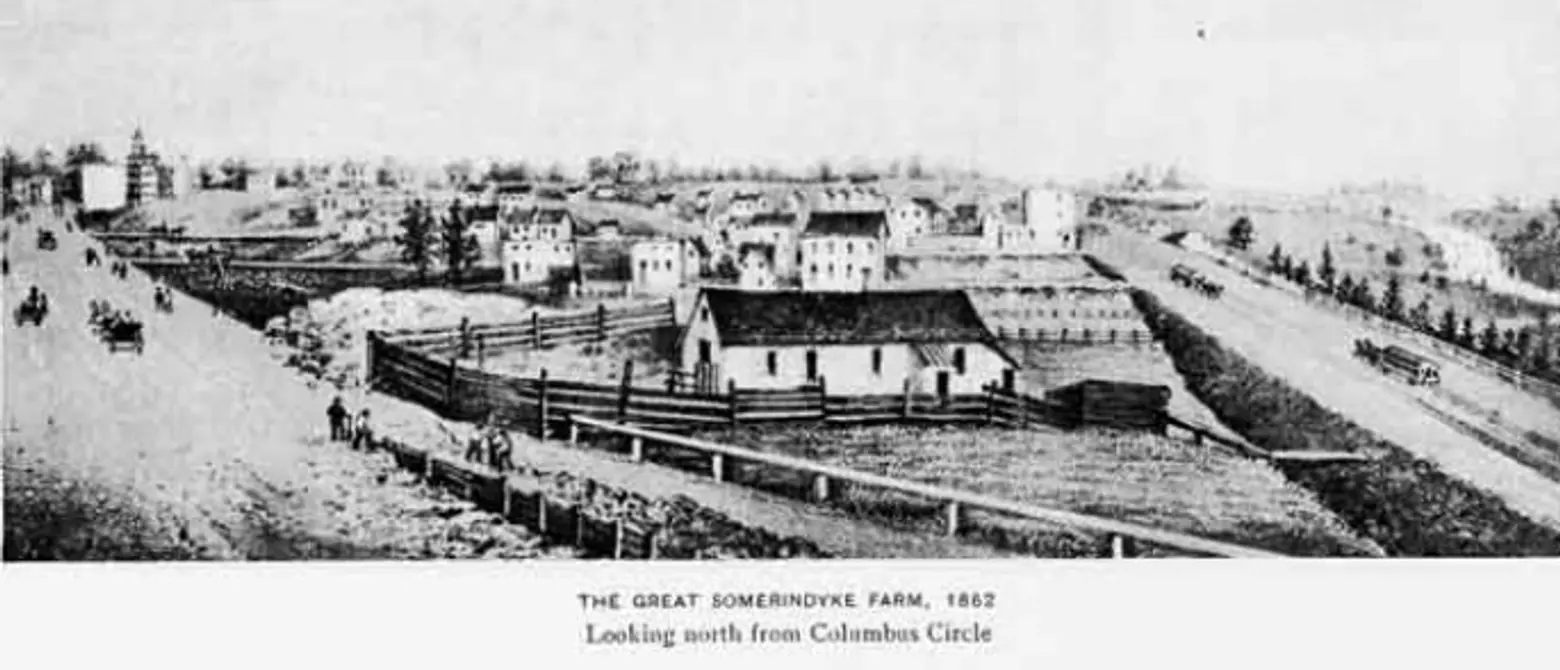

The northernmost of the Upper West Side’s lost villages, Carmansville stretched from about 140th to 158th Streets (the exact location is up for debate), today’s Hamilton Heights. It was named after the wealthy contractor, Richard Carman, who founded the area and lived on 153rd Street. He was a box manufacturer who got rich in the real estate and insurance businesses after the Great Fire of 1835. He was also friends with naturalist John James Audubon, who had his estate called Minniesland at 156th Street.

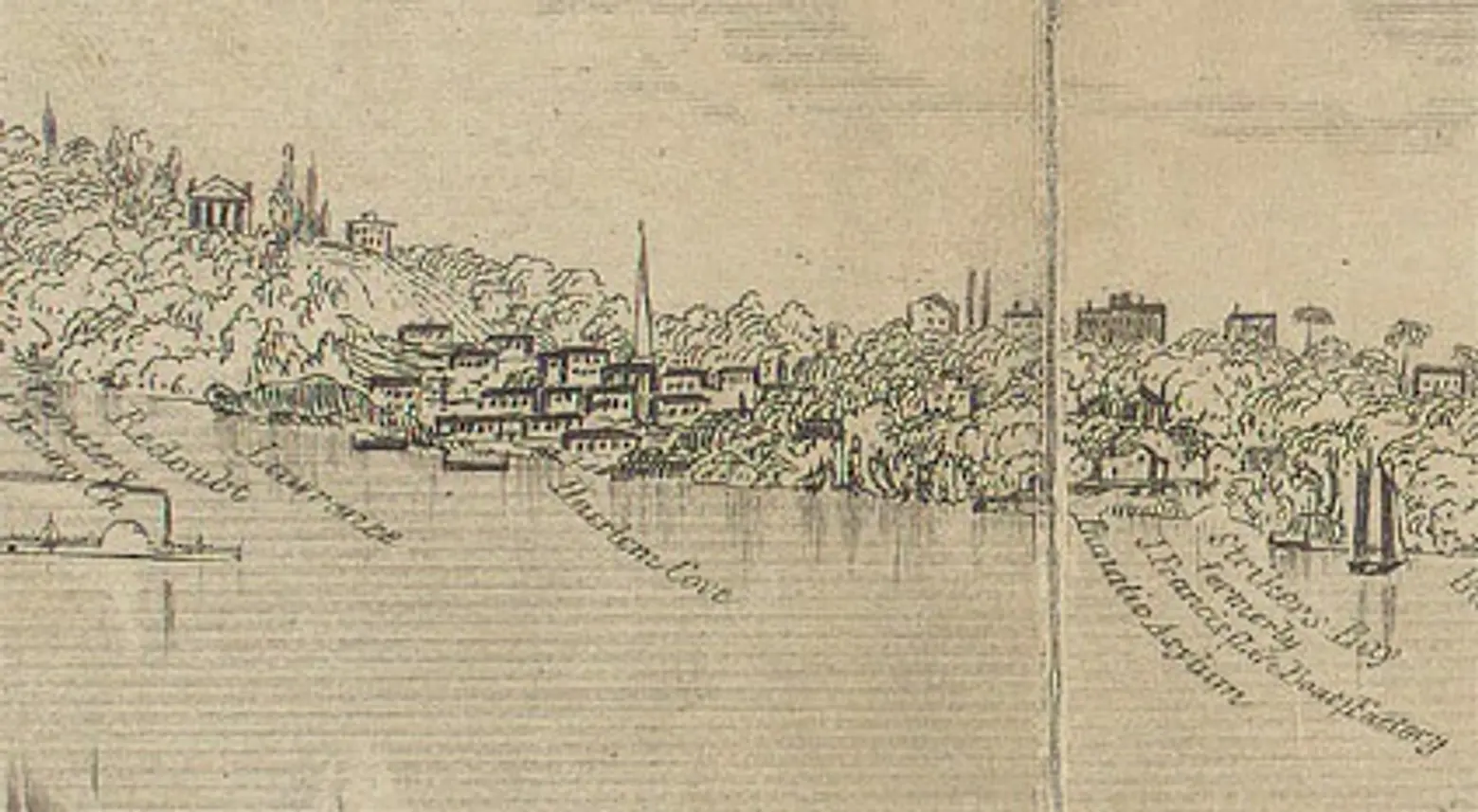

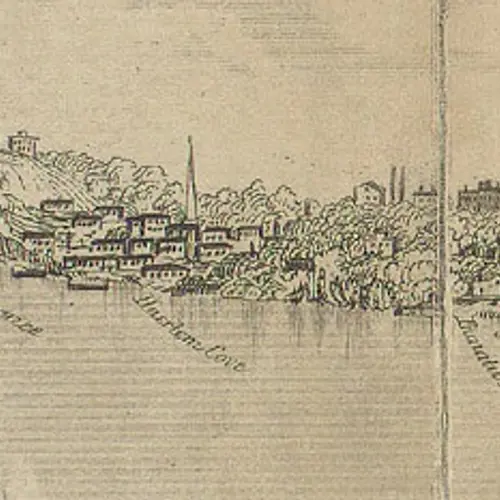

Carmansville, from an 1863 edition of Phelps’ New-York City Guide; via NYPL

Carmansville, from an 1863 edition of Phelps’ New-York City Guide; via NYPL

It was a popular neighborhood for socially prominent families. An 1868 issue of the Atlantic Monthly described the setting: “Trim hedges of beautiful flowering shrubs border the gravel walks that lead from the road to the villas. Cows of European lineage crop the velvet turf in the glades of the copses. Now and then the river is shut out from view, but only to appear again in scenic vistas.” By the end of the 19th century, the views had become obstructed with tenements and apartment buildings for middle-class families, and most of the wealthy residents moved out. Carmansville Playground today serves as a reminder of this lost hamlet.

+++

RELATED: