How Alphabet City’s ‘milk laboratory’ led to modern pasteurization

Nathan Straus’ First Milk Depot, opened in the summer of 1893, courtesy of the Augustus C. Long Health Sciences Library, Columbia University

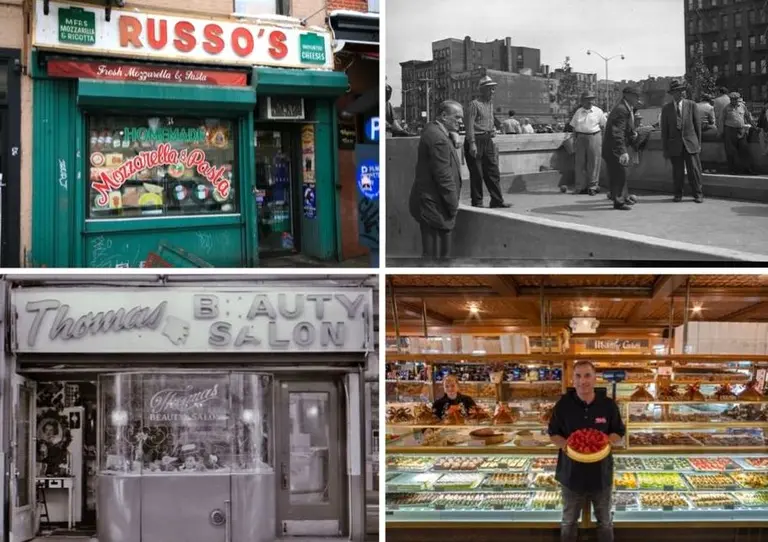

The utilitarian building at 151 Avenue C between 9th and 10th Streets would hardly elicit a second glance from the casual passerby today. But its unassuming looks belie the incredible story of how Gilded Age science and philanthropy converged here to save thousands of children’s lives. In the 1800s, intestinal infections and diseases like tuberculosis caused by bad milk was running rampant in the city’s child population, especially in poor communities like the Lower East Side. To combat the problem, Macy’s co-owner Nathan Straus instituted a program to make pasteurized milk affordable or even free. And on Avenue C, he set up a “milk laboratory” to test the dairy and distribute millions of bottles.

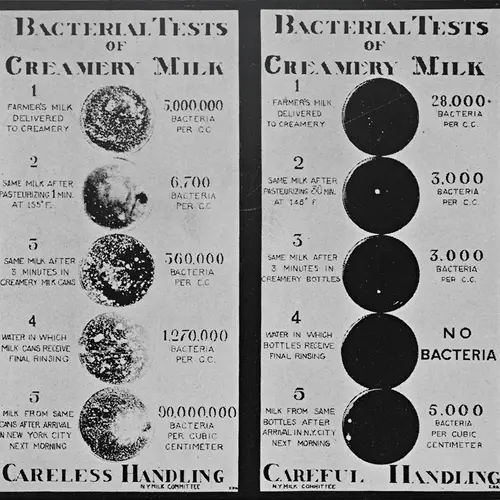

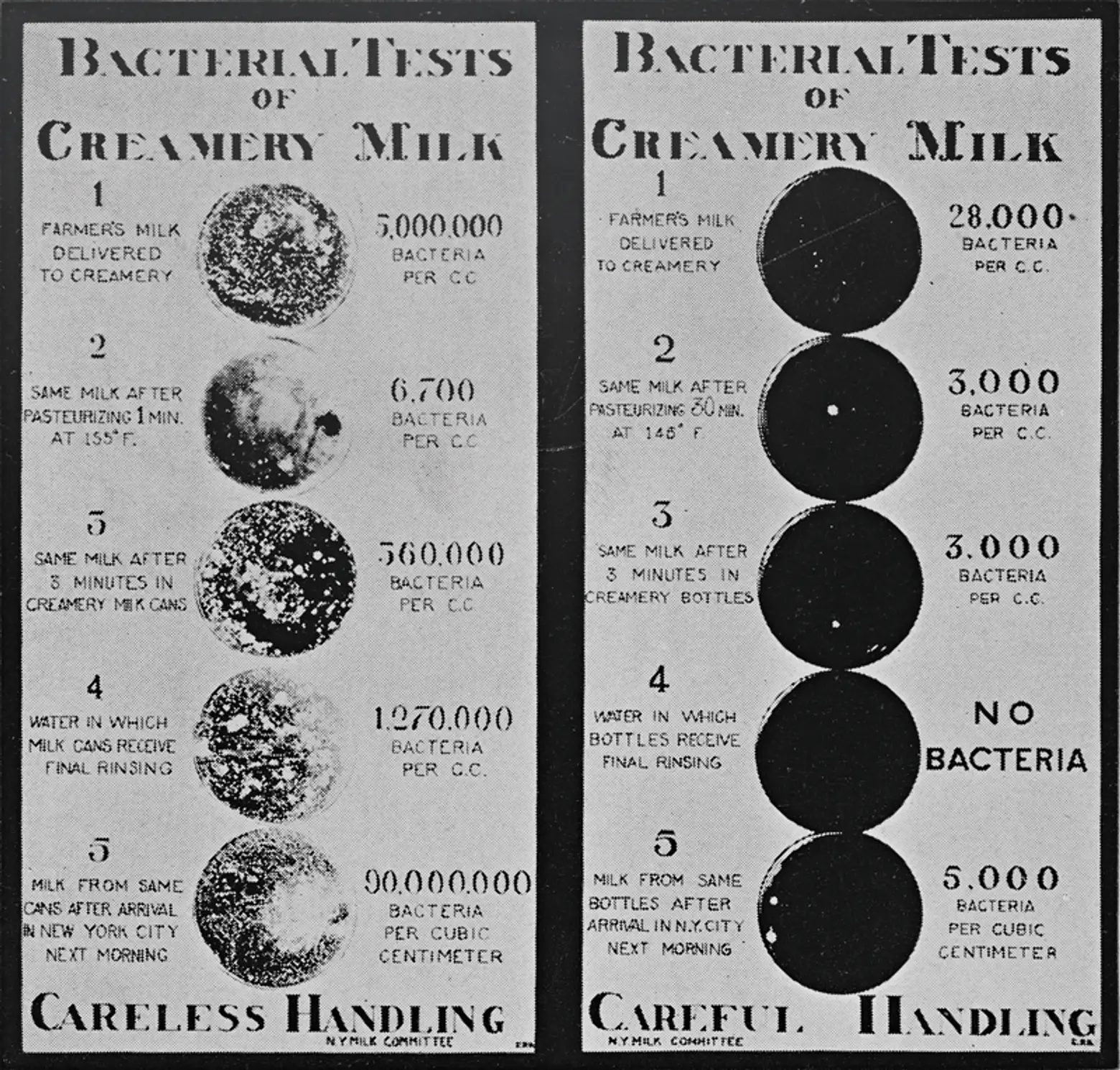

A chart from the New York Milk Committee, courtesy of Augustus C. Long Health Sciences Library, Columbia University

In the mid-19th century, the leading causes of child mortality were diseases like tuberculosis spread by milk; in 1841, half of all children under the age of five in New York City died, many from the type of intestinal infections bad milk could lead to. In 1891, bad milk was directly linked to 23 percent of the deaths in children under three in New York City. This was especially so in the impoverished, overcrowded and often fetid environment of the Lower East Side.

In the early 19th century, cows were still kept in urban areas as a source of milk, thus keeping the product fresh and disease-free. But as cities grew, cows and other livestock were banished from cities, and supply lines for milk and other products extended, increasing the opportunities for spoilage. But establishing the connection between bad milk and disease was hard to do, especially as some milk-borne diseases like Tuberculosis had long incubation periods. As the connection became clearer, processes like sterilization were introduced to make milk safe; but they were expensive, and often dramatically altered the food’s taste.

The pasteurization process, introduced in the late 19th century, offered a way to make milk safe without affecting the taste. But even as the need for such a process became clearer, the mechanism for making pasteurized milk widely available, especially where it was needed most, did not exist.

The Presbyterian Church Milk Depot at the Morningside Presbyterian Church, courtesy of the Augustus C. Long Health Sciences Library, Columbia University

Along came Nathan Straus, co-owner of Macy’s Department Store and a philanthropist with a keen focus on making New York City’s milk supply safe, especially for the immigrant poor. Starting in 1893, Straus set up a series of “milk depots” throughout Lower Manhattan where safe, pasteurized milk could be made available for just a penny a glass. Mothers who could not afford the price were eligible for vouchers to cover the cost. The first of these depots was located at the Third Street Recreation Pier along the East River. But these and other milk dispensaries needed a supply of safe milk, and that’s where 151 Avenue C came in.

Straus knew that a “milk laboratory” was needed, where milk could be tested to ensure the pasteurization process worked and that it was safe for distribution to the masses. In 1894 he commissioned architect John B. Snook, who designed the first Grand Central Station and both Vanderbilt Mansions on Fifth Avenue, to design a modest, two-story structure to fit this bill. He located it in the midst of the teeming Lower East Side ghetto, not far from the Third Street pier and the waterfront district where so many of New York’s neediest lived.

In 1894 when the lab opened, around 34,000 bottles of safe, pasteurized milk a day were distributed from the site, mostly within the neighborhood. By 1905, that number rose to 3 million bottles a day, for distribution throughout Manhattan and Brooklyn.

The results spoke for themselves. During the first decade of the Avenue C Milk Laboratory’s operation, the child mortality rate in New York City was cut nearly in half, from 126 in 1,000 to 74.5. Straus expanded his array of milk pasteurization and dispensing facilities not only throughout New York but in cities across the United States. He also began to sell home pasteurization machines at an affordable price so New Yorkers of modest means could make their milk safe if they could not get to his milk dispensaries or they were out of milk.

Straus’ lab unsurprisingly attracted considerable attention, and in 1905 the New York City Health Department came to test for itself the veracity of his claims. They found that, in fact, Straus was able to take milk which had been infected with microbes that caused tuberculosis and other infectious diseases and make it free of bacteria. By the early 1910s, New York City mandated the pasteurization of milk sold within its bounds.

Before that, however, the demand for Straus’ pasteurized milk had become so great that he needed to create a much larger facility. So in 1908, he opened a new larger milk lab at 348 East 32nd Street, where the Kips Bay housing complex now stands.

151 Avenue C in recent years, via the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation

151 Avenue C in recent years, via the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation

After Straus’ milk lab moved out, 151 Avenue C went on to many colorful if less consequential lives. It housed a cleaning and dyeing business, and then in 1930, the ground floor was converted into an auto repair shop with a billiards club above it. For most of the past several decades, the building has housed some sort of bar, club, or lounge, with “Studio 151” the most recent occupant. So while drinks have continued to be served at 151 Avenue C throughout much of its life, they were of the life-saving variety for only a dozen or so years around the turn of the last century.

+++

This post comes from the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Since 1980, GVSHP has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid.

RELATED: