How New York City’s female teachers led the charge for ‘Equal Pay for Equal Work’

With public schools back in session as of today, let’s remember that it was from the classrooms of New York City that the call for “Equal Pay for Equal Work” was sent thundering around the world.

In 1893, Kate Hogan graduated from NYU Law School with the first class of women allowed to earn JDs. By 1906, she was working as a seventh-grade teacher in Manhattan. At the time, the starting salary for a male teacher in the New York City public schools was $900 per year, but a woman in the same position earned just $600. Seeing no justice in that situation, Hogan founded the Interborough Association of Women Teachers. The Association’s mission and cry: “Equal Pay for Equal Work.”

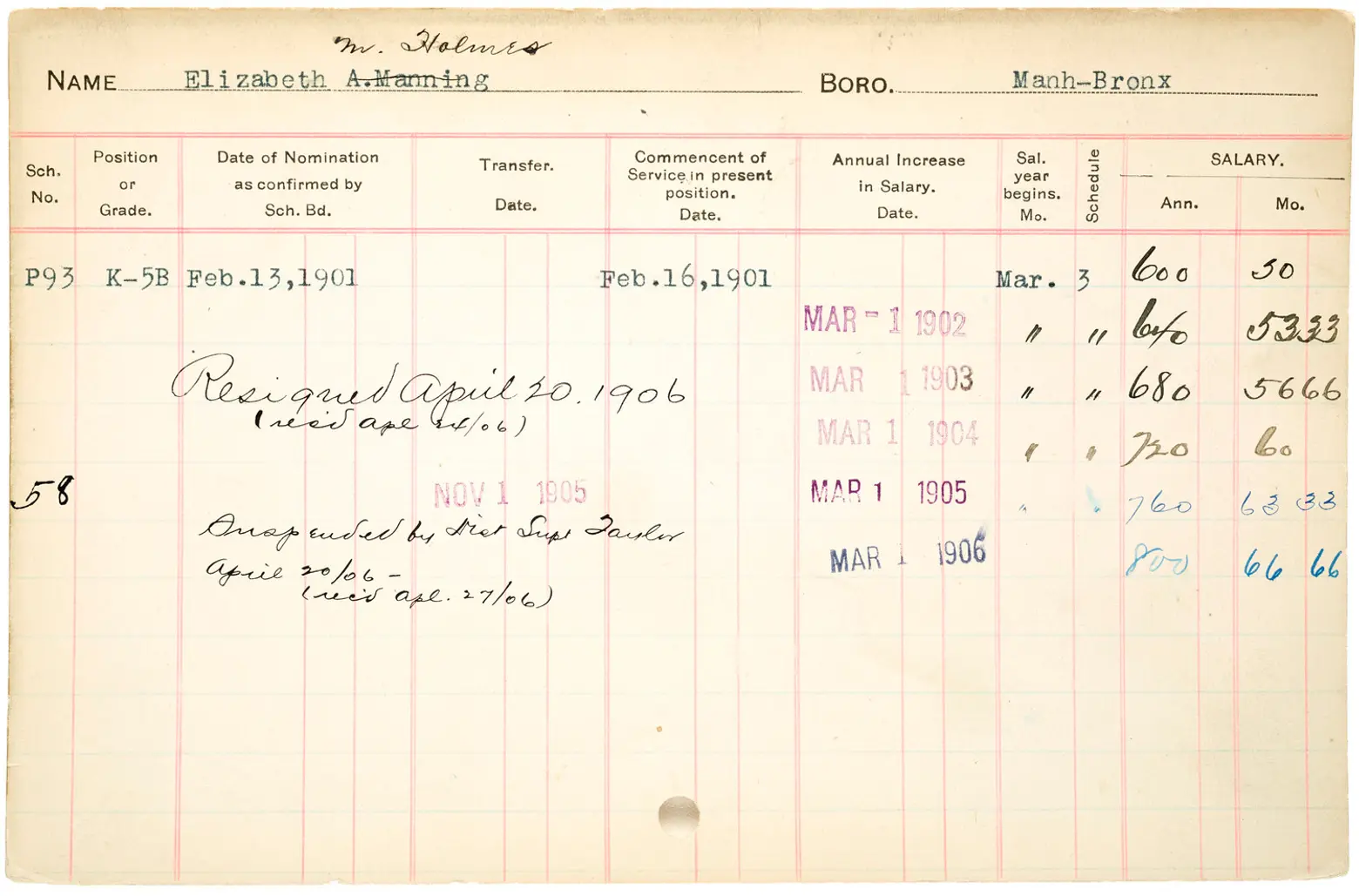

This 1906 pay record reflects women teacher’s starting salary of $600/year, via The Municipal Archives

By the time the Association held its first mass meeting in the old City College building on 23rd Street, membership was already 4,000 strong. The women knew, “The time is ripe to establish the principle of equal pay for equal work.”

They asked, “Why should a woman’s minimum annual salary be $300 less than a man’s, and why should her maximum salary be $960 less than a man’s? The women teachers do the same work, are exempt from no rules or duties, and most of them have fathers, mothers, sisters or brothers dependent upon them. Why, then, should women not receive the same salaries?” They resolved to “make a strong, united effort to bring about a consummation of what is so manifestly just.”

After Hogan’s sudden death, Grace Strachan led that effort. In 1907, she led over 600 women into the halls of the Albany Legislature to attend a hearing of Senator Horace White’s equal pay bill; in 1911, she led all 15,000 members of the Association to victory.

Over the staunch objection of the Board of Education, and dedicated opposition of groups like the Association of Men Teachers and Principals of the City of New York, Mayor Gaynor signed a bill requiring equal pay for male and female teachers in New York City.

Over the staunch objection of the Board of Education, and dedicated opposition of groups like the Association of Men Teachers and Principals of the City of New York, Mayor Gaynor signed a bill requiring equal pay for male and female teachers in New York City.

During a jubilant victory celebration in the assembly hall of the Metropolitan Building on October 23rd, 1911, Strachan joked, “You know, it was of great surprise to me to know that the Board of Education did not approve of this.” Amidst the laughter, she observed, “There is one thing upon which we can congratulate ourselves – that everything we did was above board.”

But Strachan knew the movement was bigger than the New York City Board of Education. In solidarity, she wrote in 1910, “The Interborough Association of Women Teachers of the City of New York sends greetings to all its sisters and promises that the degradation and belittling will disappear ‘as the mists of the morning.’ The recognition of women is but in its morning.”

RELATED:

- University in Exile: How refugees at the New School helped win WWII and transform American scholarship

- Back to school with C.B.J. Snyder: A look at the architect’s educational design

- Women’s History Month began in New York in 1909 to honor the city’s garment workers’ strike

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.