How NYC brought Christmas tree markets to the U.S.

A Christmas tree market in front of the Barclay Street Station circa 1895. Photo via the Library of Congress

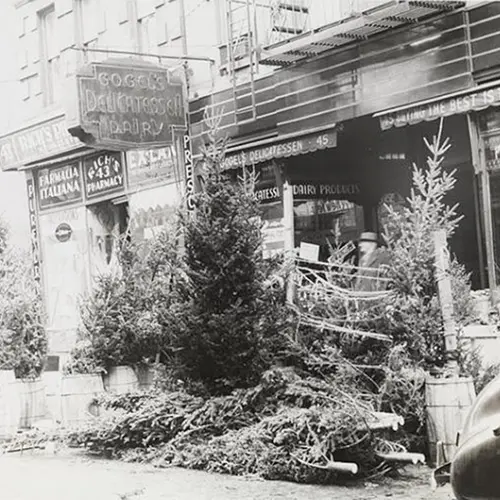

The convenience of walking to the corner bodega and haggling for a Christmas tree is something most of us take for granted, but this seasonal industry is one that actually predates Christmas’ 1870 establishment as a national holiday and continues to be a one-of-a-kind business model today. In fact, in 1851, a tree stand set up for $1 at the west side’s Washington Market became the nation’s very first public Christmas tree market, the impetus behind it being a way to save New Yorkers a trip out of town to chop down their own trees. Ahead, find out the full history of this now-national trend and how it’s evolved over the years.

A man hauling Christmas trees from a horse-led wagon ca. 1910-1915. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

A man hauling Christmas trees from a horse-led wagon ca. 1910-1915. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Before the mid-1800s, few traditions existed for Christmas in the United States – Santa and Rudolph were both decades away from creation, let alone popularity, along with most other capitalistic customs. In parts of Europe, however, the Christmas tree had long existed as a pre-Christian ritual, and while the Dutch had first brought it to America, the wave of German immigrants in the 1840s helped popularize it Stateside.

“Load of Xmas trees, N.Y.” Ca. 1910-1914 via the Library of Congress.

But in New York City, only the wealthy or those with a horse and wagon had the means to travel into the country to cut down their own trees. As legend has it, a “jolly woodsman” and Catskill landowner named Mark Carr saw the business opportunity behind this, and two weeks before Christmas in 1851, he and his sons cut down a couple dozen fir and spruce trees and loaded them onto two ox sleds en route to Manhattan.

Carr set up shop on the corner of Greenwich and Vesey Streets, and New Yorkers were so excited to either be spared the trip out of town or be able to purchase their own tree for the first time, that he sold out of his entire tree stock within a day, thus birthing the tradition.

Christmas tree market ca. 1910-1915 courtesy the Library of Congress.

Following Carr’s success, many others followed suit, bringing trees to the city around the holidays to capitalize on demand. Chopping trees in greener pastures and hauling them to the profitable west side markets of Manhattan (there located because of the proximity to the docks) quickly became its own industry, with over 200,000 trees being shipped annually to NYC by 1880. A standard tree sold for between $8 and $10, a whopping $200 in today’s money.

In Carr’s time, vendor regulations were few and far between, but now, Christmas tree peddlers stand out as one of the least regulated trades. The sale of “coniferous trees” is almost at loophole level as compared to the rest of city’s street vending regulations, but it’s not an accident that Christmas trees don’t require a license to be sold in the month of December.

In the 1930s, former Mayor Fiorello La Guardia was on a city-wide mission to reduce street peddling by establishing regulations that would require vendors to apply for selling permits. This factored into his “war on Christmas,” in which he mainly targeted immigrant vendors by adding the business obstacle of getting a license to sell. But in 1938, after much public outcry, the City Council adopted what’s come to be known as the “coniferous tree exception,” which allows vendors to sell Christmas trees on the sidewalk during the month of December without a permit as long as they have permission from the owners of whatever establishment fronts that swath of sidewalk and they keep enough space open for pedestrians.

A Christmas tree stand at 6th Avenue and 14th Street. Image: 6sqft

A Christmas tree stand at 6th Avenue and 14th Street. Image: 6sqft

Though NYC’s Christmas tree sidewalk business retains its inherent charm, today business owners are often hyper-competitive with one another. Two salesmen were convinced they’d have their kneecaps broken if they didn’t pay off their neighbor, and certainly, there is evidence of Christmas tree company employees being fired and left unpaid for talking to the press, Priceonomics reported in a profile of two tree vendors.

While the City of New York auctions off a number of prime park-side permits (which can cost up to $25,000 in fees), many vendors set up shop with more personal permissions, like the OK of any business they pitch their wares in front of. Thus, the industry arguably comes largely down to who you know, how well you’re liked, and how generously you pay off or otherwise compensate the businesses near your site of sale.

In addition to the competition from other local tree vendors, there’s also the threat of corporate companies like Home Depot and Whole Foods who have the ability to buy en masse and price trees far cheaper than little guys are capable of. “We can’t compete with that,” smalltime tree vendor Heather Neville told the Times in 2017, referring to Whole Foods’ cross-city November offering of a 40 percent discount on seven- to eight-foot Fraser firs. For more local outlets, pricing that low is simply not viable if there’s to be any hope of churning a profit.

Compared to Yuletide trees’ in the mid-19th century, prices have increased exponentially for all vendors. This is compounded by a shortage of trees (Christmas trees take 7-10 years to grow to their full size). According to the National Christmas Tree Association, the median price for trees in 2019 was $76.87, but just about six years ago, they were significantly lower, most being in the $30 range.

Despite the drama, however, evergreen wonderlands continue to grace city streets each December, a more aromatic and immersive holiday custom than even the city’s better-known shop window displays.

RELATED:

- New York City was home to America’s first-ever electrically lit Christmas tree

- 104 years ago, the nation’s first public Christmas tree went up in Madison Square Park

- The history of the Rockefeller Center Christmas Tree, a NYC holiday tradition

Editor’s Note: This story was originally published on December 20, 2017 and has been updated.