How researchers used NYC buildings to measure the 1925 solar eclipse

Postmaster General Harry Stewart New watches the solar eclipse of January 24, 1925, shielding his eyes with a photographic plate. Image: Wikimedia commons

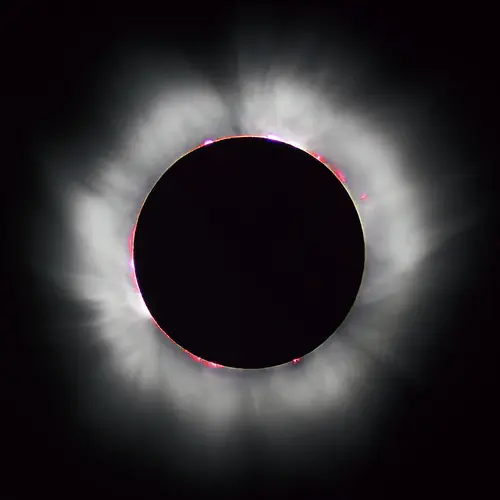

During a total solar eclipse that occurred in 1925 in Manhattan, according to Space.com, “the streetlights turned on, three women fainted, vendors sold smoked glass while exhorting passersby to ‘save your eyes for 10 cents’ and seagulls landed in the water, assuming it was night.” Though today’s eclipse will be only a partial version for New Yorkers, we know enough about the moon’s orbit to accurately predict an eclipse’s timing as narrowly as a city block’s distance. At the time, though–long before anyone had landed on the moon, observing and measuring the shadow as it moved over the Earth provided important information on the moon’s size, shape, and path.

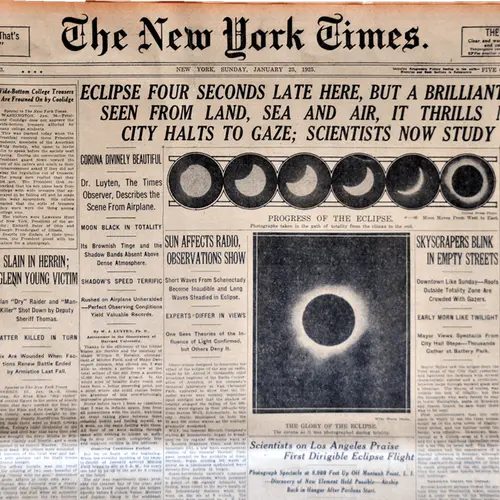

The 1925 eclipse, in typical New York fashion, was fashionably late, a fact which made the cover of The New York Times. “The moon was unpunctual, as well as careless of its route,” according to the Times article, “It was about four seconds late in blotting out the sun.” Watchers in Manhattan just above 96th Street on Jan. 24, 1925 got an eyeful as researchers scrambled to take measurements of the event.

Dr Sam M. Burka (left), a physicist at McCook Field, Ohio and Lt. George W. Goddard prepare for photographing of solar eclipse 24 January 1925 by the United States Army Air Service. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Twenty-five planes took measurements from the air, a dirigible hovered 8,000 feet above Long Island and 149 observers on foot lined Upper Manhattan block by block to document the sun’s exact southern limit; cameras outnumbered people at every turn.

So great was the imperative to record the celestial event that even the most ad hoc efforts resembled military maneuvers. One study done by New York’s electric companies sent 149 observers to rooftops and bridges. The watchers were divided into groups of two and three stationed along 135th Street on Manhattan’s West Side. Within the groups, one person would watch for the moon’s incoming shadow while another noted whether the sun was totally covered by the moon.

The shadow watchers had an impossible task: The shadow travels at an average of 2,300 mph and is hard to quantify. Everyone above 96th Street saw the moon completely covering the disk of the sun, though no one below 96th Street could. That experience represented a victory in measurement: The eclipse’s southern border could be pinpointed to within 225 feet, or the distance between 230 Riverside Drive and 240 Riverside Drive. The shadow’s border was literally caught between two buildings, each on its own city block.

The New York Edison Company’s team also measured the city’s use of electrical power during the eclipse. As predicted, power use rose during the few minutes of darkness, but use was lower in some places because many industries were shuttered for the morning.

Today’s eclipse could be the most-watched in history according to NASA, and we still have a lot to learn, so amateurs and professionals will get another rare chance to work together to gather more data on the moon’s moves. And cameras will definitely outnumber people (most of whom have at least one on their person at all times as it is). Observation projects include the University of California and Google’s Eclipse Megamovie project and another by the International Occultation Timing Organization who have called for volunteers to document the event.

[Via Space.com]

RELATED:

- MOON lamp uses NASA-sourced data to replicate lunar phases in your living room

- Star Power: Celestial ceilings and zodiac symbols in New York architecture

- John Jeffries is considered America’s first weatherman

- An architect’s 1969 nuclear shelter plan shows a mini-Manhattan built thousands of feet underground