In the 1800s, a group of NYC artists and writers created the modern-day Santa Claus

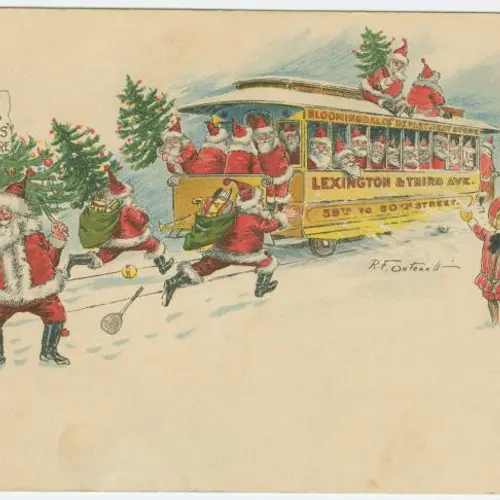

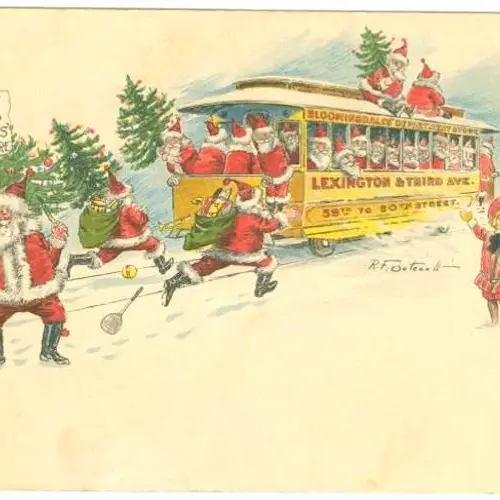

Ever the New Yorker, Santa catches the trolly to Bloomingdales! The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library, NYPL Digital Collections

Saint Nicholas arrived in New York with the Dutch and became the Patron Saint of New York City in the early 19th century, but Santa, as we know him, is a hometown boy. New York’s writers and artists were the first to depict the modern Santa Claus, transforming the figure of Dutch lore into a cheerful holiday hero. The illustrious Claus gained his sleigh in Chelsea and his red suit on Franklin Square. With a little help from the likes of Washington Irving, Clement Clarke Moore, and Thomas Nast, jolly old St. Nick became the merriest man in Manhattan.

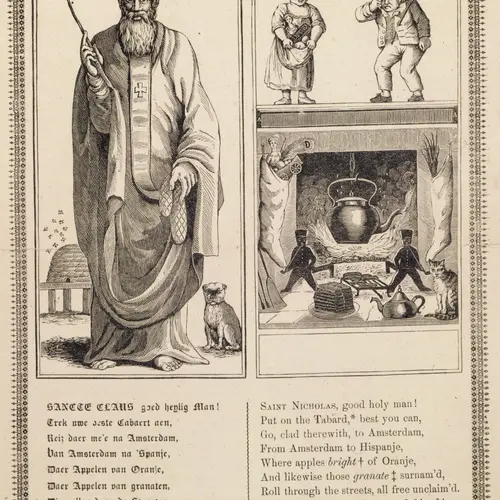

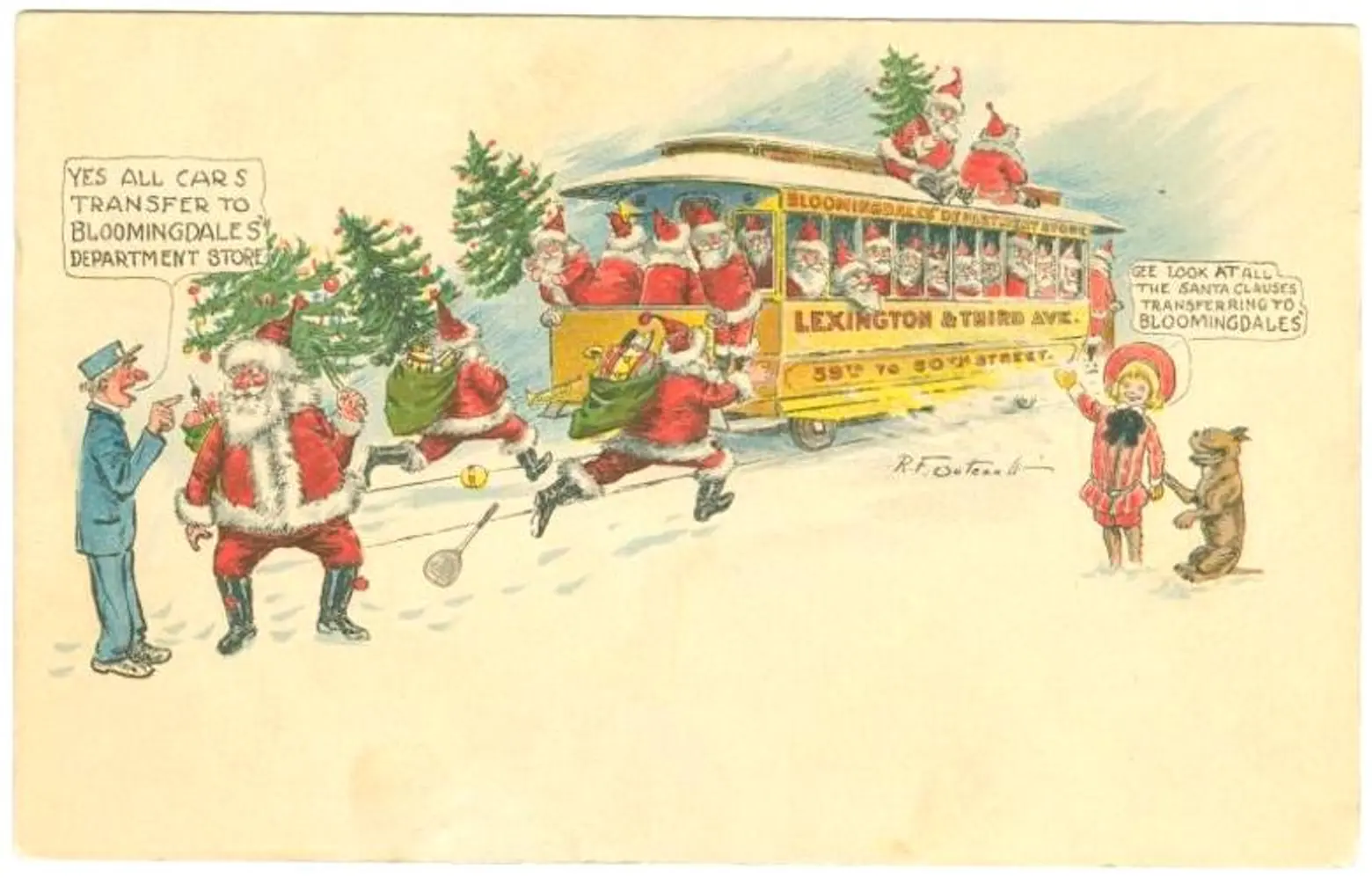

Print of St Nicholas by John Pintard (1810); courtesy of the New-York Historical Society via Wikimedia

In 18th-century New York, Santa was, first and foremost, a revolutionary. At that time, Claus was held up as a hero by John Pintard, founder of the New-York Historical Society. Pintard was a patriot who served in the Revolution and was good friends with George Washington. Accordingly, he became interested in New York’s Dutch history as a matter of anti-British sentiment: Because Saint Nicholas was revered in the Netherlands as the Patron Saint of Children, Pintard considered him to be a worthy anti-British symbol and meaningful link to New York’s Dutch past.

Pintard lobbied to have St. Nick formally declared Patron Saint of New York City, and in the early 1800s, he began to celebrate the festival of Saint Nicholas at the New-York Historical Society. In 1810, prominent New Yorkers gathered at NYHS on December 6, the saint’s feast day, to toast “Sancte Claus.” Many New Yorkers, including the writer Washington Irving, got caught up in the festivities surrounding Saint Nick.

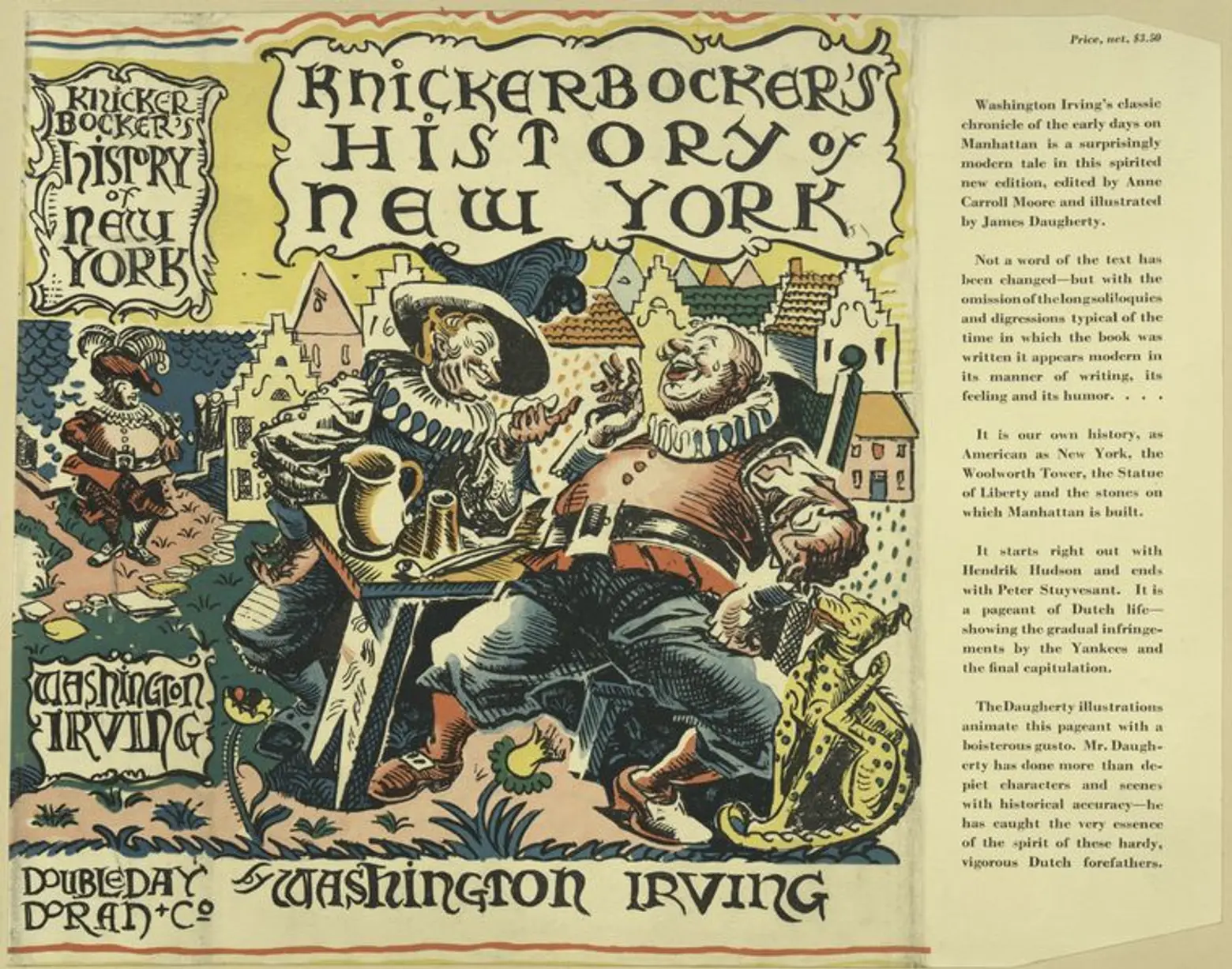

Irving established the legend of St. Nick in New York, as well as the legend of Knickerbockers. A Knickerbocker is defined as “a descendant of the early Dutch settlers of New York; broadly: a native or resident of the city or state of New York —used as a nickname.” But, it wasn’t the Dutch in New Amsterdam who proudly referred to themselves and their progeny as “genuine Knickerbockers,” it was Washington Irving.

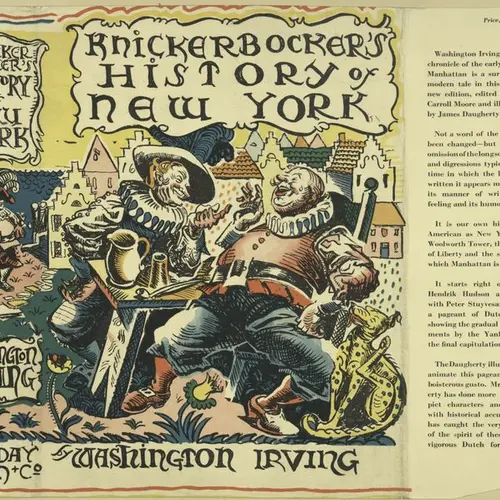

In 1809, Irving penned Knickerbocker’s History of New York, under the pseudonym Diedrich Knickerbocker. The two-volume tome is a fanciful satire of the Dutch period, and St. Nick is central to the narrative.

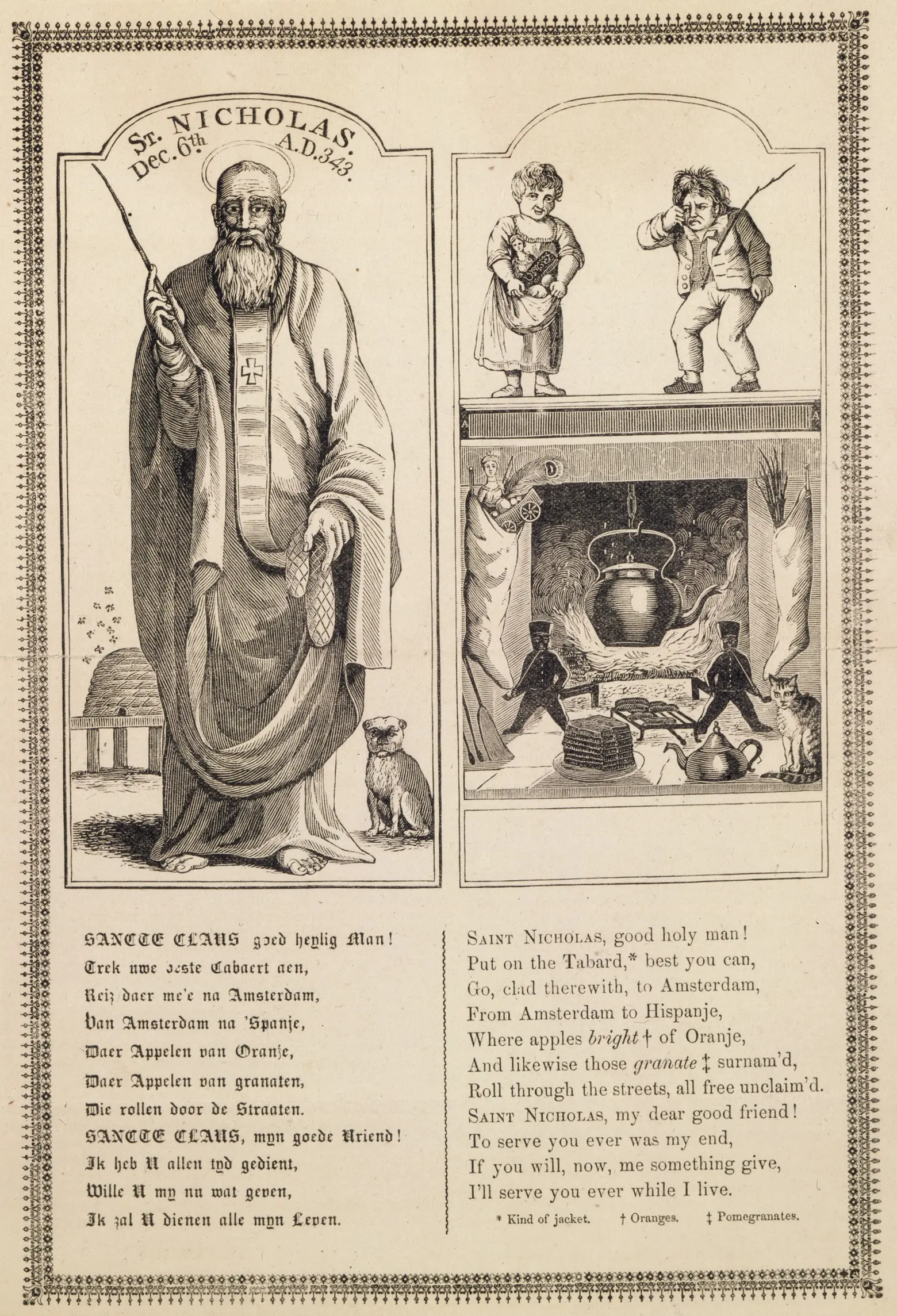

Book jacket for Knickerbocker’s History, 1929 General Research Division, The New York Public Library. (1928). Knickerbocker’s History of New York. NYPL Digital Collections.

The original work claimed to represent “the very life and soul of history,” but Irving wrote in 1848 that to create the narrative, he reached “back into the regions of doubt and fable,” adding “figments of [his] own brain,” and “imaginative and whimsical associations,” to “the peculiar and racy customs and usages derived from our Dutch progenitors.”

And it’s with quite a lot of whimsy, in Knickerbocker’s History, that Santa finds his way to New Amsterdam. According to the tale, St. Nicholas adorned the first ship that carried the Dutch to Manhattan, and the saint watched over the voyage. He was “equipped with a low, broad-brimmed hat, a huge pair of Flemish trunk hose, and a pipe that reached to the end of the bow-sprit.”

Some of the characteristics we see in Santa today are present in Knickerbocker’s Saint Nick. For example, he appears in a dream sequence “riding over the tops of the trees, in that self-same wagon wherein he brings his yearly presents to children.” In that dream, he guides the Dutch to Bowling Green to build their fort and their city.

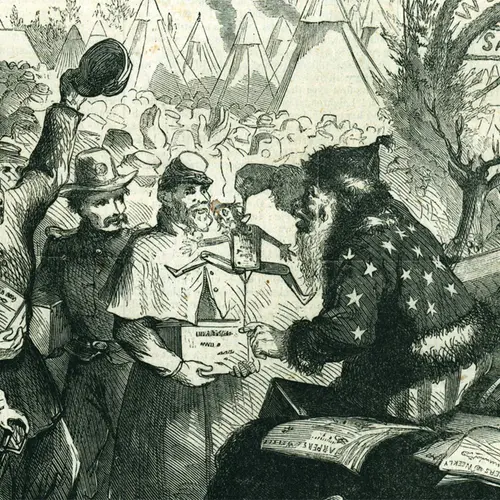

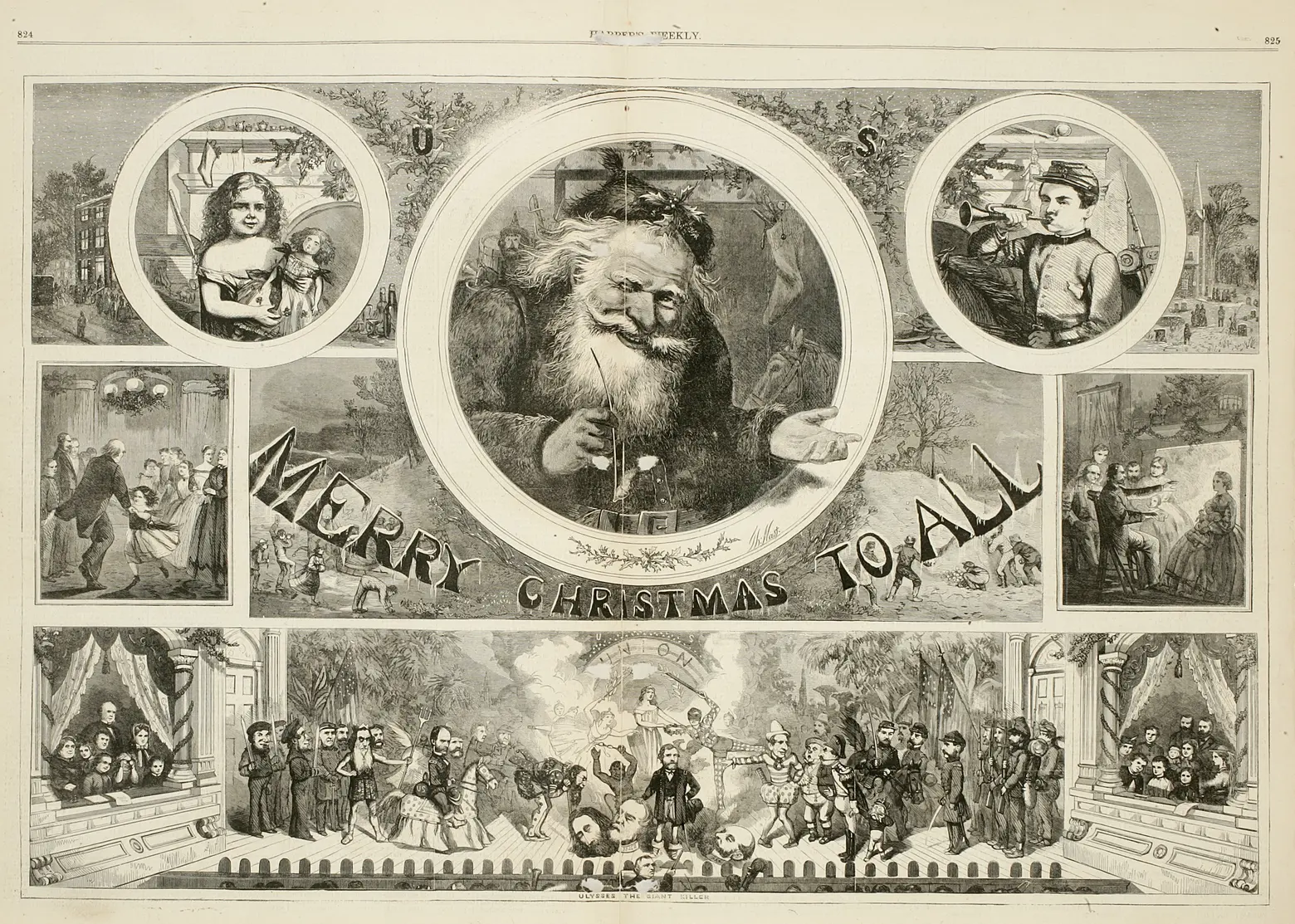

Harper’s Weekly, December 29, 1865; courtesy of the New-York Historical Society via Wikimedia

To thank him for his invaluable eye for real estate, writes Knickerbocker, the citizens of New Amsterdam “instituted that pious ceremony, still religiously observed in all our ancient families of the right breed, of hanging up a stocking in the chimney on St. Nicholas Eve; which stocking is always found in the morning miraculously filled; for the good St. Nicholas has ever been a great giver of gifts, particularly to children.”

To go with the stockings, Knickerbocker tells us, New Amsterdam residents “built a fair and goodly chapel within the fort, which they consecrated to [Saint Nicholas]; whereupon he immediately took the town of New Amsterdam under his peculiar patronage, and he has even since been, and I devoutly hope will ever be, the…saint of this excellent city.”

By the early 19th century he was indeed the patron saint of this excellent city, but by the 1820s, he’d be more than sacred, he’d be downright merry. In 1822, when Clement Clarke Moore, the scion of one of New York’s most illustrious families, penned “Twas The Night Before Christmas (A Visit from Saint Nicholas),” he became the first to describe the modern Santa Claus.

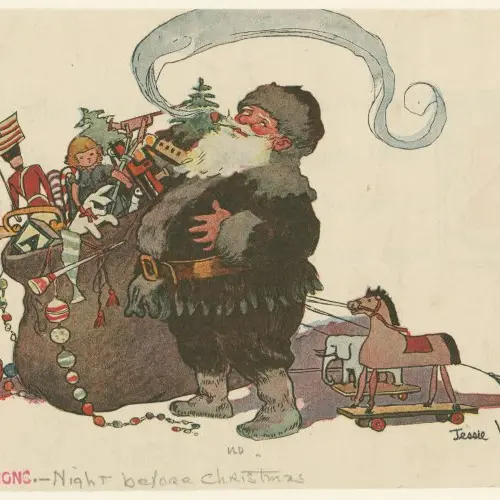

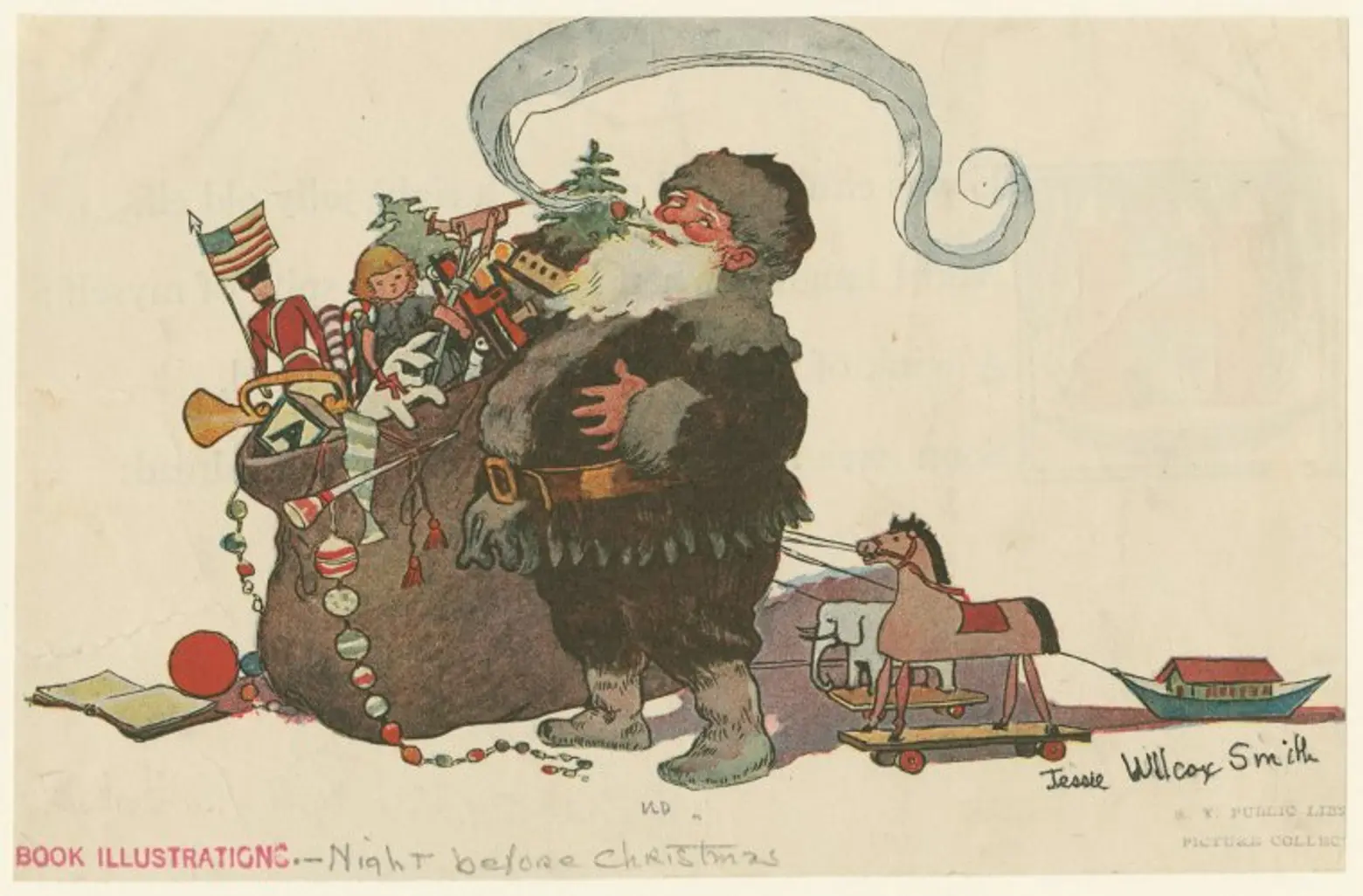

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf, NYPL Digital Collections

The Clarke family owned land from 19th-24th streets and from 8th to 10th Avenues, where they built an estate called Chelsea. Benjamin Moore, Clement’s father, assisted in officiating at George Washington’s Inauguration, read last rites to Alexander Hamilton, and at various times throughout his life served as rector of Trinity Church, Bishop of New York, and President of Columbia University.

Clement Clarke Moore was a professor. He originally wrote “The Night Before Christmas” to entertain his six children, basing his version of Santa Claus on a plump Dutch neighbor. “The Night Before Christmas” has been called “the greatest piece of genre word-painting in the English language,” because it set the standard for the Jolly Saint Nick we know. The poem marks the first time that Santa is described as riding a sleigh (instead of a wagon, like he does in Knickerbocker’s History) or having “a round belly…like a bowlful of jelly.” Today’s Claus, “cubby and plump, a right jolly old elf,” debuted here.

The sleigh that inspired Santa’s seems to have been Moore’s own. He was said to have come up with the poem while riding his sleigh through a snowy Chelsea. While Moore’s sleigh was driven by slave labor, the sleigh he gave Santa was pulled by reindeer.

Moore was the first to fix the number of Santa’s reindeer at eight, and to name them, but his name was not initially associated with “The Night Before Christmas.” The poem was first published anonymously in the Troy Sentinel on November 23, 1823, but in 1829, the editor of the Sentinel revealed that the author belonged “by birth and residence to the City of New York.”

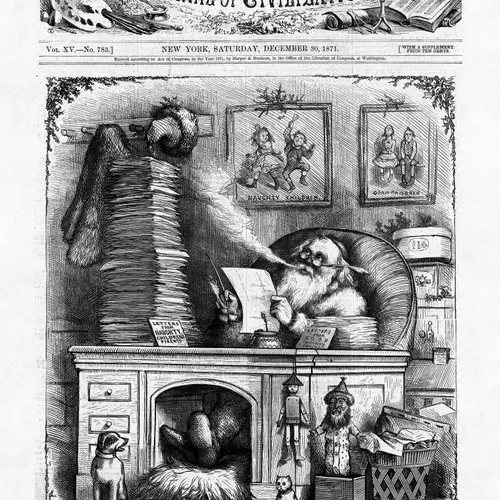

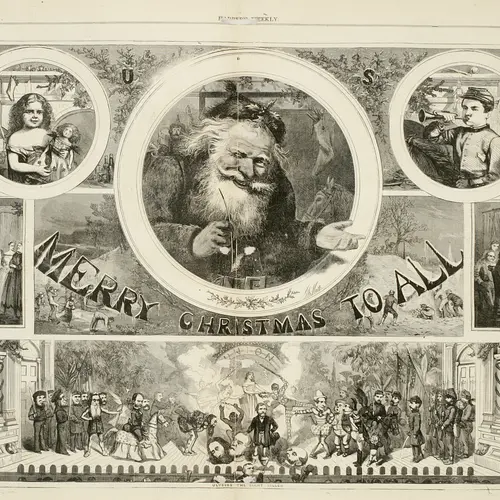

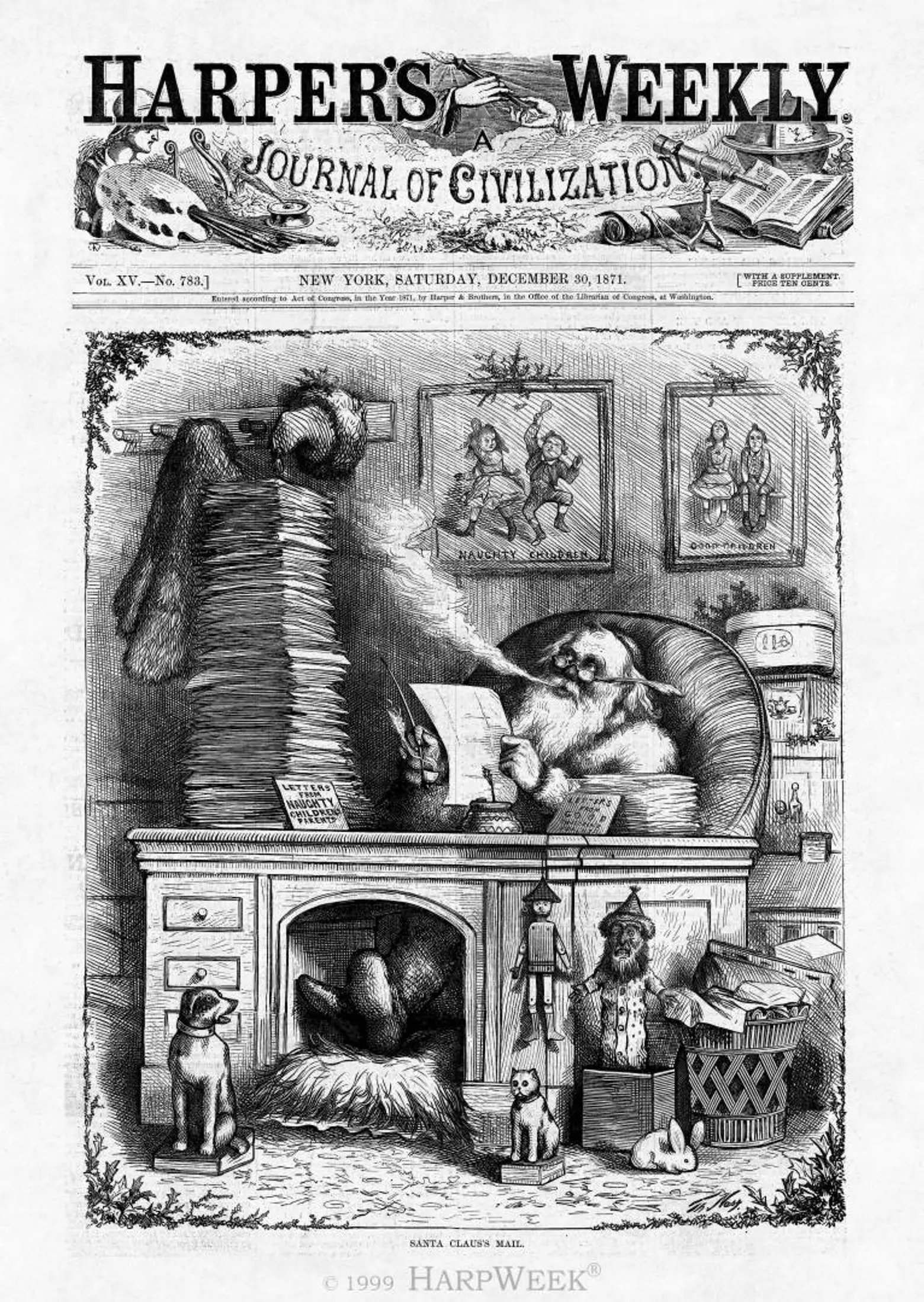

Thomas Nast, “Santa Claus’s Mail,” Harper’s Weekly, December 30, 1871, reproduced 1999, via NYPL

While Moore was the first to describe the modern Santa, the cartoonist Thomas Nast was the first to depict him as the jolly man we know. From his desk at Harper’s Weekly on Lower Manhattan’s Franklin Square, Nast created the now-iconic image of a red-suited Claus.

In the first half of the 19th century, Santa came in all shapes and sizes, as a myriad of artists tried their hands at bringing him to life. The German-born Nast based his image of Santa on Moore’s descriptions and his knowledge of German folklore. Nast codified Santa’s look – giving him a white beard, black boots, and red suit – and captured his lifestyle: It was Nast who first fixed Santa’s home at the North Pole, and filled his toy factory with elves.

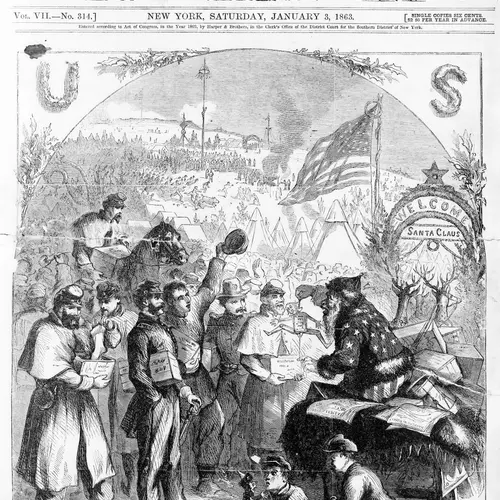

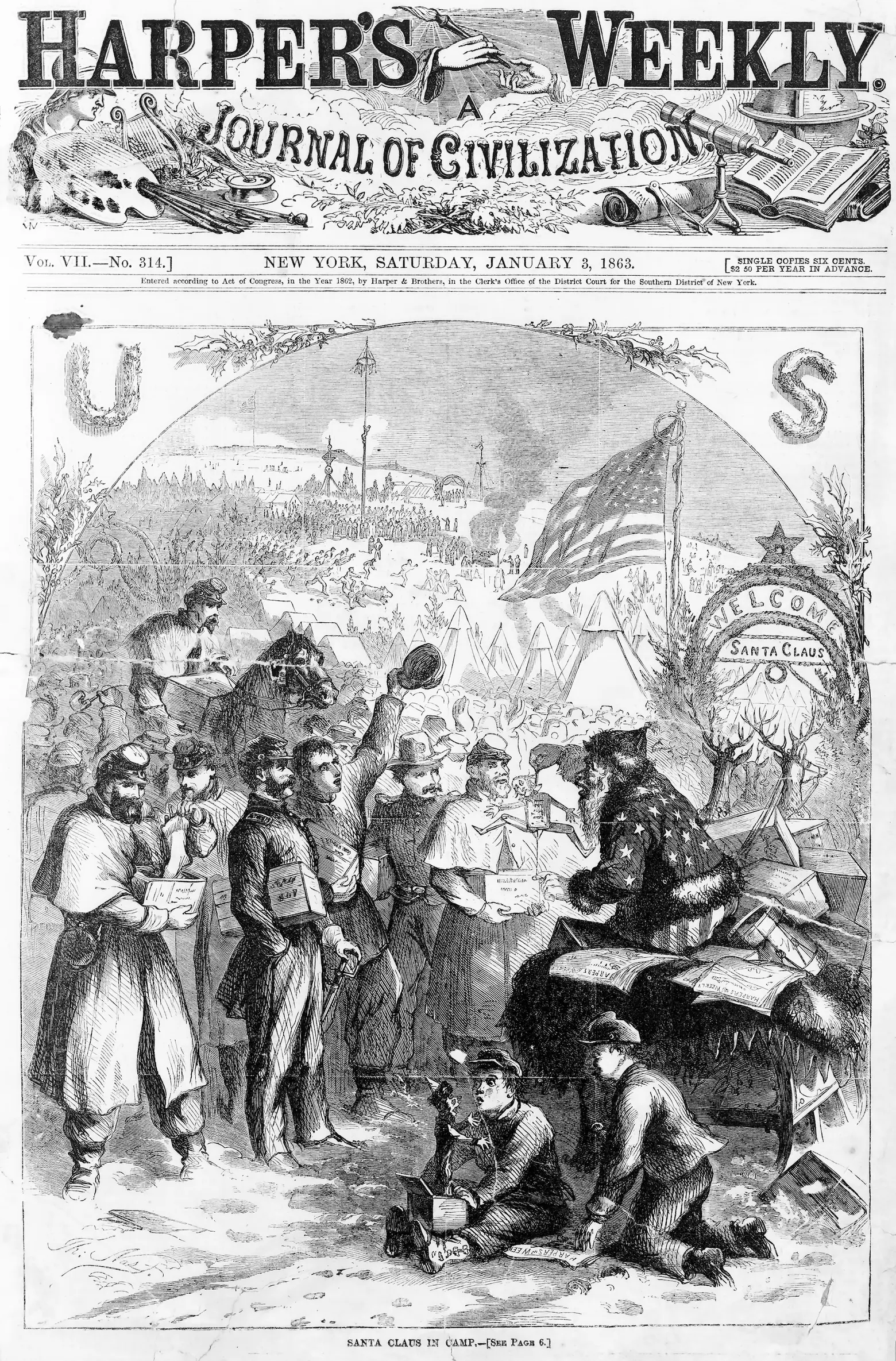

Under Nast’s pen, Santa even became a patriotic figure. Nast’s first Santa Cartoons for Harper’s weekly were published January 3rd, 1863, and show Santa Claus visiting Union Troops.

Nast’s first Santa illustration (1863); courtesy of NYHS on Wikimedia

Wherever he goes, and whoever he visits, Santa always be at home in New York.

+++

Editor’s note: The original version of this story was published on December 3, 2018.

RELATED:

- Macy’s, Lord & Taylor, and more: The history of New York City’s holiday windows

- How NYC brought Christmas tree markets to the U.S.

- The history of the Rockefeller Center Christmas Tree, a NYC holiday tradition

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.