How six Italian immigrants from the South Bronx carved some of the nation’s most iconic sculptures

When the Piccirilli Brothers arrived in New York from Italy in 1888, they brought with them a skill– artistry and passion for stone-carving unrivaled in the United States. At their studio at 467 East 142nd Street, in the Mott Haven Section of the Bronx, the brothers turned monumental slabs of marble into some of the nation’s recognizable icons, including the senate pediment of the US Capitol Building and the statue of Abraham Lincoln that sits resolutely in the Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall.

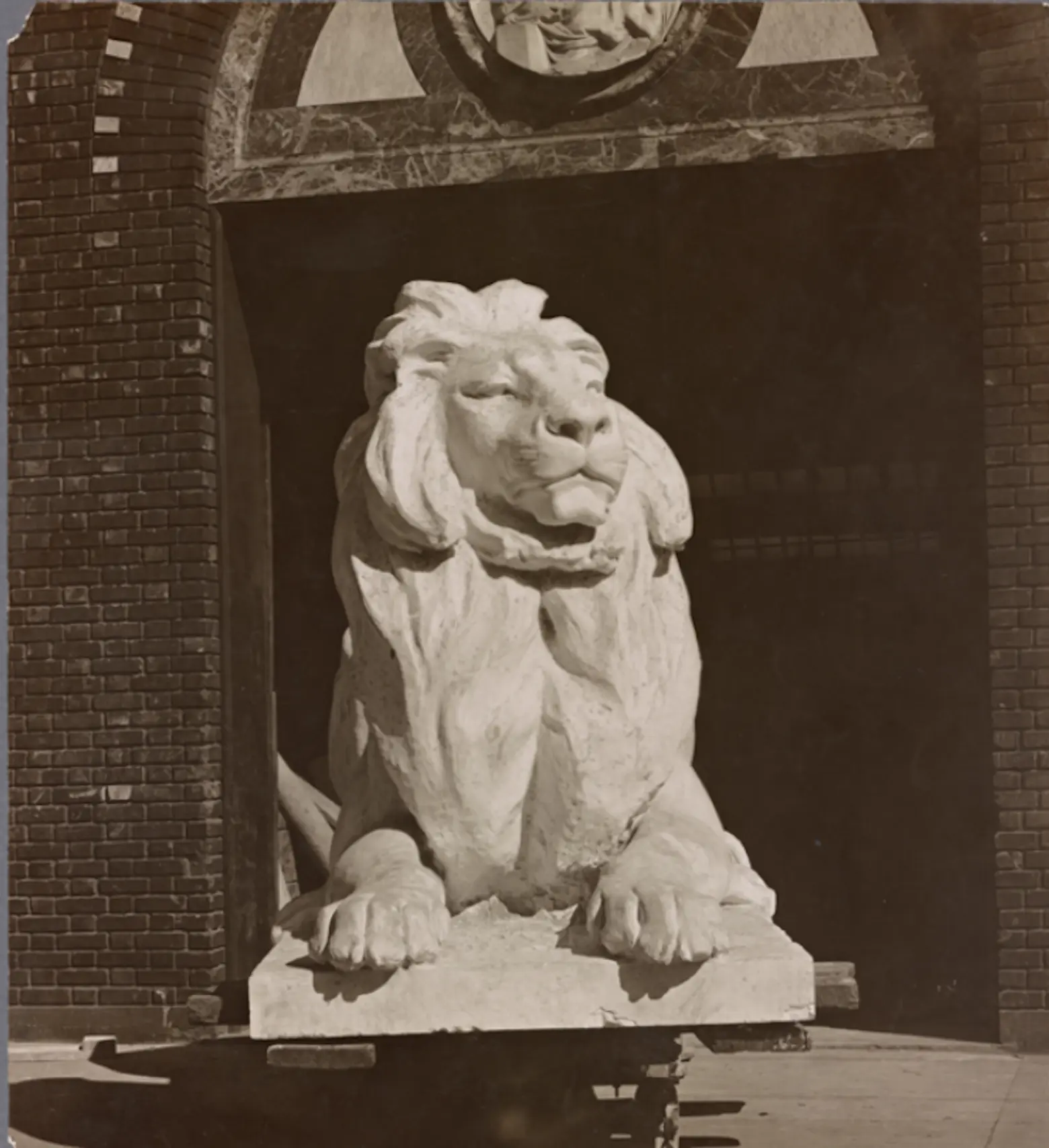

The Piccirillis not only helped set our national narrative in stone but they also left an indelible mark on New York City. They carved hundreds of commissions around the five boroughs, including the 11 figures in the pediment of the New York Stock exchange, the “four continents” adorning the Customs House at Bowling Green, the two stately lions that guard the New York Public Library, both statues of George Washington for the Arch at Washington Square, and upwards of 500 individual carvings at Riverside Church.

The New York Public Library’s South Lion at the Piccirilli Studio, via NYPL

All six brothers – Attilio, Ferrucio, Furio, Getulio, Masaniello, and Orazio – were born in Massa, Tuscany, near the renowned marble quarries of Carrara, where their father, Giuseppe, was a master carver. Giuseppe taught his trade to all six sons, and Attilio and Furio continued their studies at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Rome. Fortuitously, the Piccirillis arrived in New York at the dawn of the City Beautiful Movement (1890 – 1920), a model of city planning that sought to engender moral and social uplift through inspiring civic architecture. The movement’s monuments were wrought in the classical carving style the Piccirillis had perfected.

Albert Ten Eyck, a former sculpture curator at the Met, explained, “with the arrival of the Piccirillis, it became unnecessary for American sculptors to go to Italy to have their sculpture translated into marble. It became unnecessary, in fact, for a sculptor to know anything about stone cutting, and some were quite content to model in clay, and have all their stonework done by the Piccirillis.”

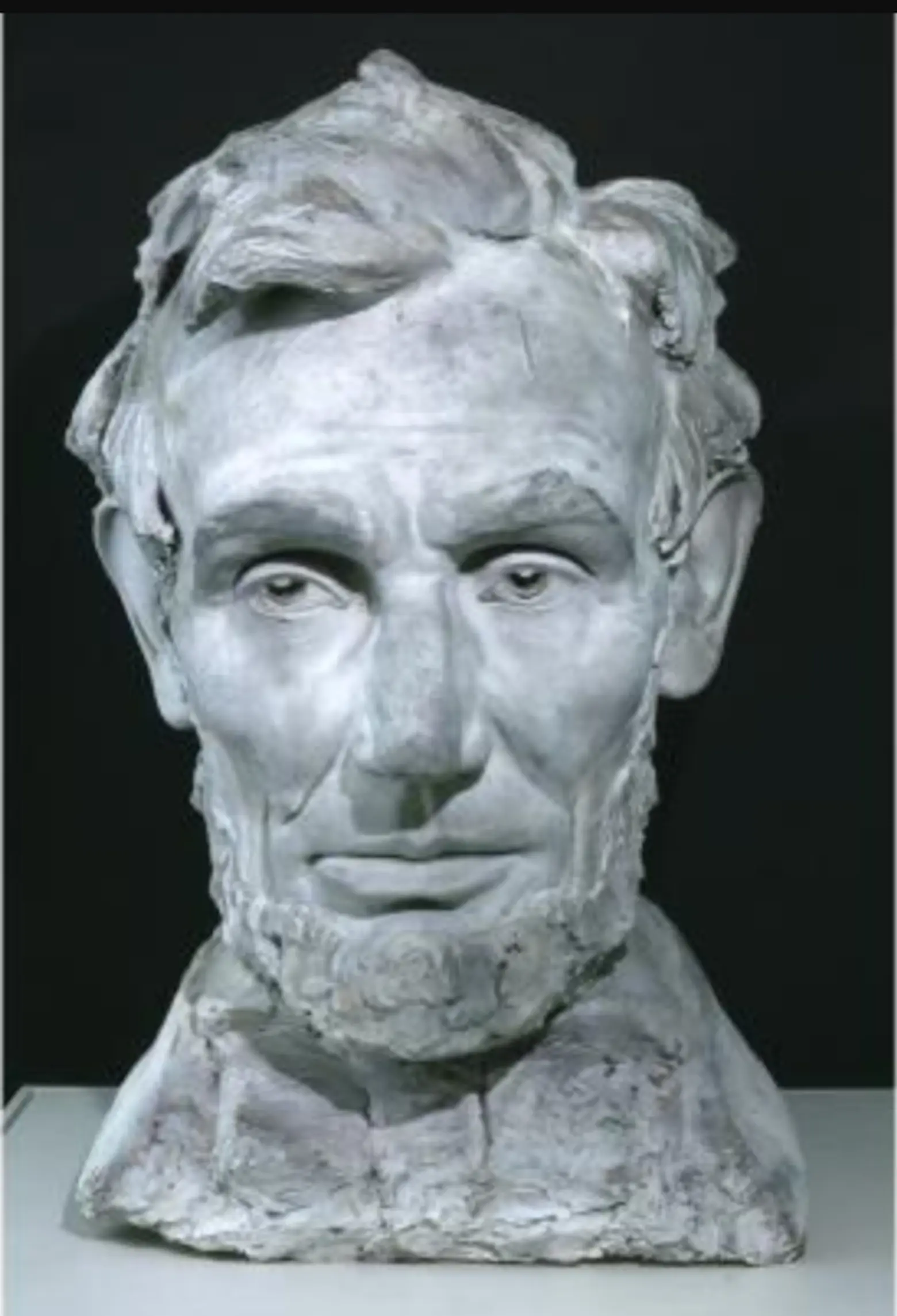

Daniel Chester French’s Plaster Head of Lincoln, via the New York Historical Society

The sculptor Daniel Chester French had this kind of relationship with the Piccirillis. French’s statue of Abraham Lincoln for the Lincoln Memorial would be the brothers’ most celebrated carving, but it was just one of dozens his designs they executed. After meeting the Piccirillis, French employed the brothers on all but two of his marble commissions.

French was not alone. To meet the demand, the brothers established the largest sculpture studio in the country, and were “known from coast to coast in all large cities, wherever architects and sculptors congregate.” From their Bronx studio flowed marble masterpieces so finely wrought, the American Magazine of Art noted in 1921, that the brothers’ work “celebrates the natural bond between art and craftsmanship. They have brought us from their native land the whole art and craft and science and business of freeing the angel from the stone.”

They each won several honors for their work: Ozario, Attilio and Furio were individually awarded the Ellin P. Speyer Memorial Prize by the National Academy of Design; Getulio was celebrated for having carved the pediment sculptures of the New York Stock Exchange when he was just 18 years old; and Attilio, who became the most famous among the brothers, was commissioned not only to carve but also to design several sculptures around New York, including the Fireman’s Memorial on Riverside Drive, the Maine Memorial at Columbus Circle, and Youth Leading Industry at Rockefeller Center.

The Piccirillis saw each individual honor as a shared prize. Art Digest reported in 1935 that the brothers always used “we” when referring to their work, owing to their “close and effective” teamwork. That camaraderie mirrored the way they worked: The brothers were known to break into song as they carved, and Attilio often cooked lunch for the entire workshop.

In 1944, Fiorello LaGuardia himself highlighted the Piccirilli joviality. Of his close personal friend, Attilio, LaGuardia wrote, “he is the most modest man that ever lived. . . . I have never heard him knock a fellow artist. I taught him how to laugh 35 years ago. We have been laughing ever since.”

The Piccirillis welcomed the world into their joyous atmosphere, hosting thousands of visitors at their 142nd street studio including Teddy Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson, but the world was not always so welcoming.

The brothers faced some anti-immigrant sentiment even as they worked to realize some of the United States’ most patriotic sculptures. For example, the Art Commission of Virginia rejected Attilio’s sketches for a bust Thomas Jefferson, noting that the name Piccirilli would not be welcome in Virginia. Similarly, The Lincoln Memorial Commission rejected French’s suggestion to have “Piccirilli” inscribed on the pedestal of the Lincoln Memorial.

The Lincoln Memorial via the National Parks Service

In fact, it was unusual for the Piccirilli name to be inscribed anywhere. The brothers often toiled in anonymity, and as classical, figurative sculpture lost favor to more modern styles in the 1920s and ‘30s, their relationship to the city’s monuments faded into memory. By the 1940s, an art critic even suggested that the bronze sculptures on top of the Maine Monument be melted down for the war effort.

The Piccirilli Brothers, 1930 via the National Italian American Foundation

The Piccirilli Brothers, 1930 via the National Italian American Foundation

When Orazio, the last surviving Piccirilli brother, died in 1954, the Washington Evening Star reflected on the brothers’ contribution to American art, noting that “people who perhaps never heard their name have reason to be grateful for their labors.”

In the 21st century, grateful New Yorkers have worked to recognize those labors and honor the Piccirilli brothers. East 142nd Street Between Brook and Willis Avenues was renamed Piccirilli Place on March 25, 2004.

+++

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

RELATED:

Interested in similar content?

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

Thank you, very interesting gor us carvers.

Great article — I look forward to reading more of your research.