How the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage helped win voting rights in New York

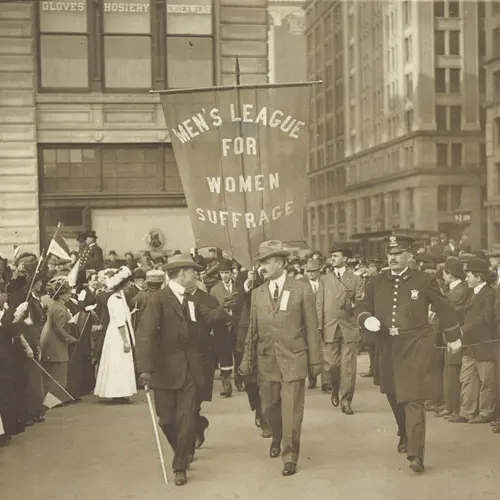

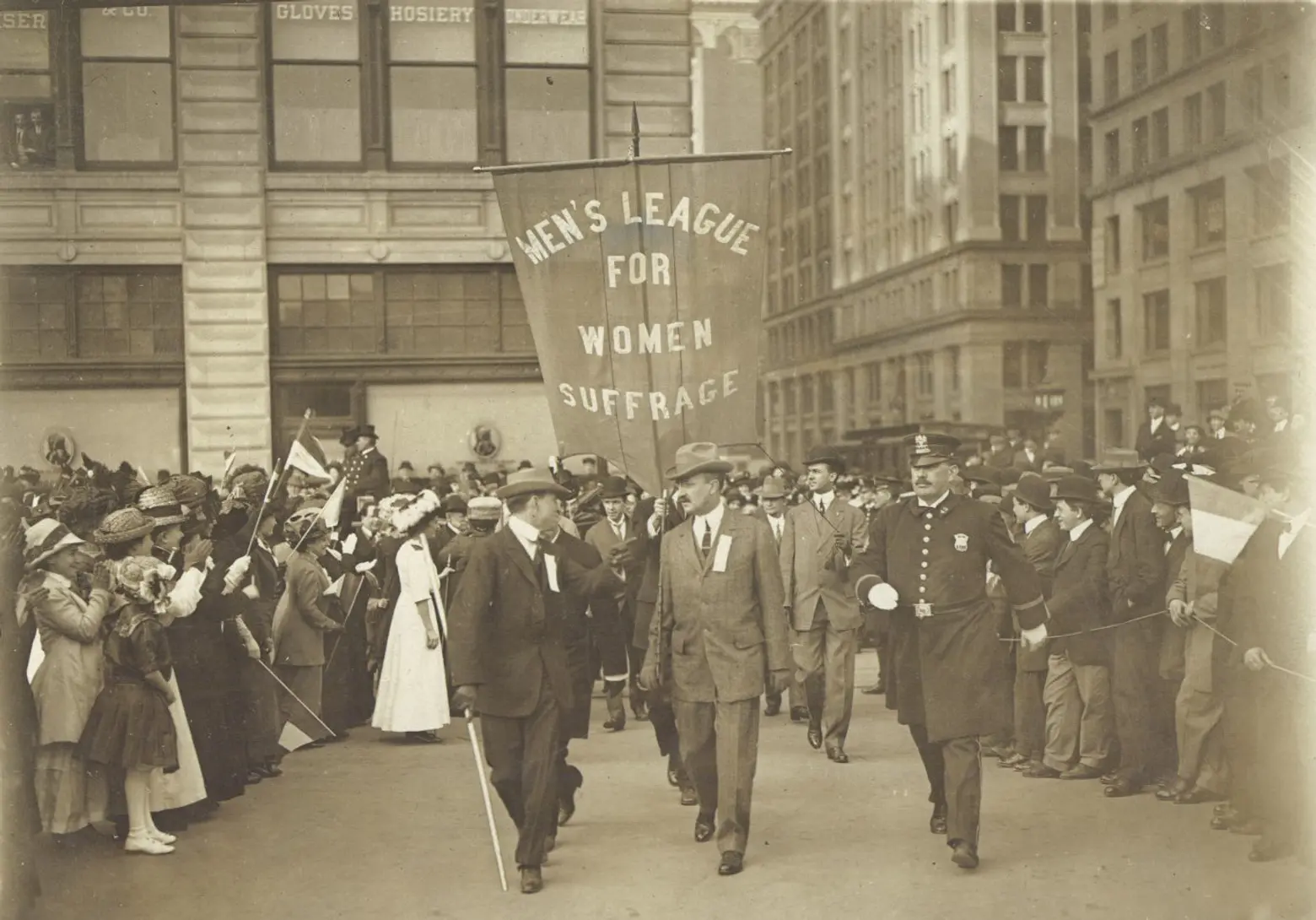

Members of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage March in a 1915 Suffrage Parade, via the Carrie Chapman Catt Papers at Bryn Mawr College

James Lees Laidlaw, the president of the National Chapter of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage, wrote in 1912, “The great educational work in the woman’s movement has been done by women, through a vast expenditure of energy and against great odds. There is still work to be done and hard work. We men can make it easier and happier work if we join in it, and no longer stand aside, as too many men have done, leaving the women to toil and struggle, making up in vital energy what they lack in political power.”

Thanks to an ongoing great expenditure of energy, American men and women will vote tomorrow. In our own time, there is still work to be done, and hard work, in the fight for equality, justice and universal dignity. The history of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage, founded in New York in 1909, offers the reminder that we all can make it easier and happier work if we join in it, and provides a stirring example of how anybody might offer organized, meaningful support to a vital cause.

International Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage Meeting, Budapest, 1913, via NYPL

In the winter of 1909, the editor of the New York Evening Post, the President of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Head of the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, the President of the National City Bank of New York, the founders of the New School, the guiding light of the Free Synagogue Movement, and members of the boards of General Electric and Standard and Poor’s all met at the New York City Club for one purpose: to support women.

These men were founding members of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage, a group of New York’s leading citizens who became passionate foot soldiers in the fight for political equality. The titans-turned-allies worked under the direction of the movement’s female leaders to support the “Great Demand” of Women’s Suffrage in the press, in the pulpit and in the halls of power.

Individually, men had always been part of the women’s movement. For example, in 1869, Henry Ward Beecher, who headed the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn Heights, was unanimously elected as the first president of the American Woman Suffrage Association.

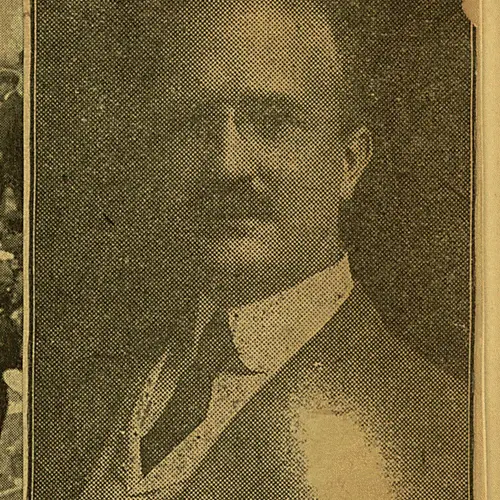

James Lees Laidlaw, ca. 1911 via the Library of Congress

James Lees Laidlaw, ca. 1911 via the Library of Congress

But the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage was something new: Its members sought not to lead the women’s movement, but to work within it. Describing how suffrage was won, and what role men had played, Laidlaw said, “The women did it. But not by any heroic action, but by hard, steady grinding and good organization.” He added: “We men too have learned something, we who were auxiliaries to the great women’s suffrage party. We have learned to be auxiliaries.”

The Men’s League began to organize as an auxiliary to the Suffrage Movement in 1908, when Reverend Doctor Anna Howard Shaw, President of the National American Women’s Suffrage Association, invited Oswald Garrison Villard, editor of the New York Evening Post, to a suffrage convention in Buffalo. Villard didn’t have time to prepare remarks for the event, but he was willing to do something even better: form a group of prominent New Yorkers whose names would drum up support for the cause.

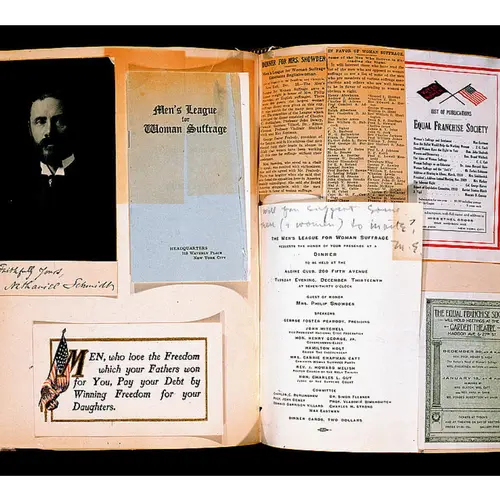

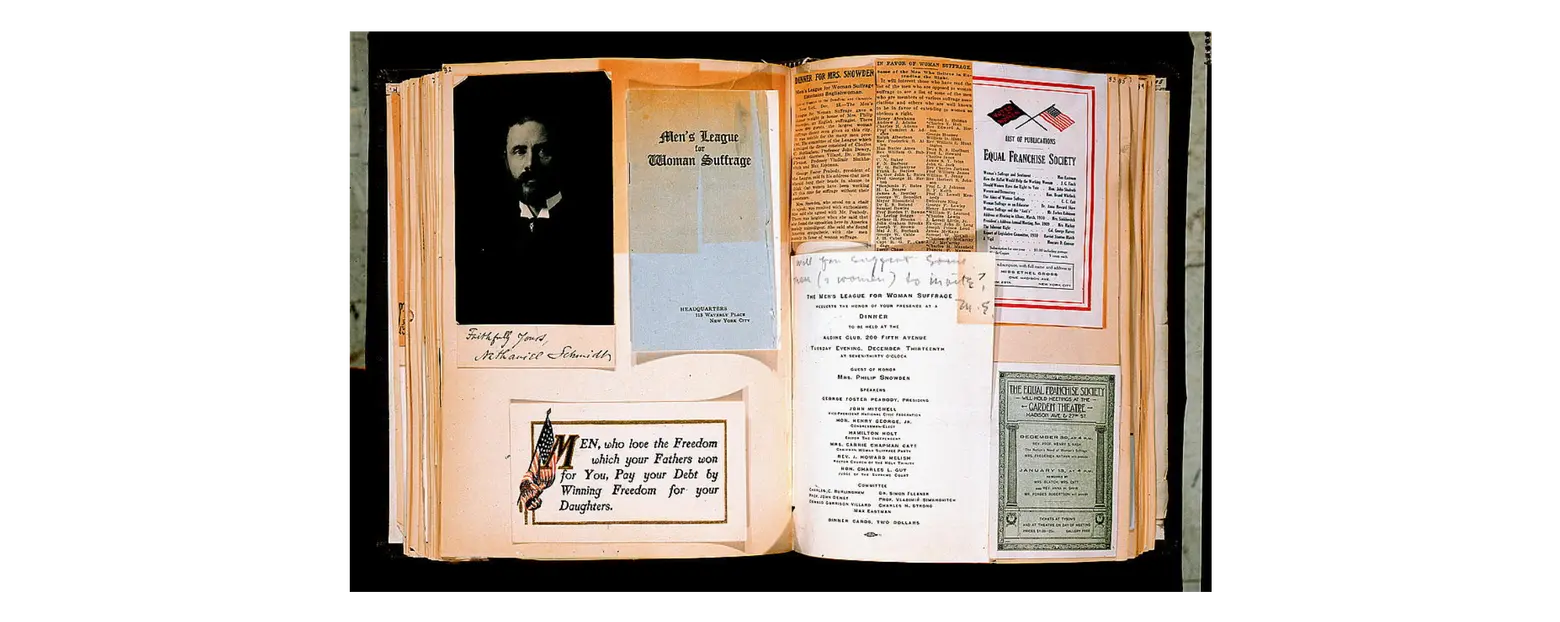

Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage, Miller Scrapbook, 1910-1911, via the Library of Congress

Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage, Miller Scrapbook, 1910-1911, via the Library of Congress

When men including editor and philosopher Max Eastman, education reformer John Dewey, Rabbi Stephen Wise, financier John Foster Peabody, Dr. Simon Flexner, and writer William Dean Howells came together to formalize that support and codify the Constitution of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage, they wrote in their charter, “the purpose of this league shall be to express approval of the movement of women to attain the full suffrage in this country, and to aid them in their efforts toward that end by public appearances in behalf of the cause, by the circulation of literature, the holding of meetings, and in such other ways as from time to time seem desirable.”

To that end, Men’s Leaguers marched in the streets, undertook nationwide suffrage tours, hosted lavish fundraisers, filled editorial pages, represented female suffragists in court, lobbied at the state and federal level for equal suffrage, and in at least one situation, performed in a suffrage-themed vaudeville routine.

All dramatics aside, the Men’s League’s Constitution had one extremely important stipulation. It said, “Any voter in the state of New York may become a member of this League.” Ultimately, the men’s status as voters made them deeply valuable to the Suffrage Movement.

“Mrs. Suffern” implores men to join the cause, 1914 , via the Library of Congress

As the Columbia social historian, New School founder, and Men’s Leaguer Charles Beard put it, “10,000 voters will have more effect upon a Congressman than all the angels.” Indeed, it wasn’t so much the Men’s League members’ social prominence as their political clout that made them strong, necessary allies to the Women’s Suffrage Movement.

The Suffrage Movement was no stranger to well-heeled support. Some of its most vocal champions and vigorous advocates were upper-class women like Alva Vanderbilt Belmont and Louisine Havemeyer, who had the time and means to devote to the movement. But, prominent men had one thing prominent women still did not: political power.

For example, Eastman, Wise, Villard and Peabody were all politically connected to Woodrow Wilson. Suffragist Inez Mulholland may have led the 1913 Suffrage Parade on horseback under a banner asking, “Mr. Wilson, how long will women wait for liberty?” But members of the Men’s League could just ask the president that question personally.

As politically enfranchised men, the League’s members had ready access to other politically enfranchised men, in the press and in the state and federal government, whose support would be necessary for women to win the vote. After all, male voters were the only ones who could vote to decide if women should have the vote. Their support was crucial.

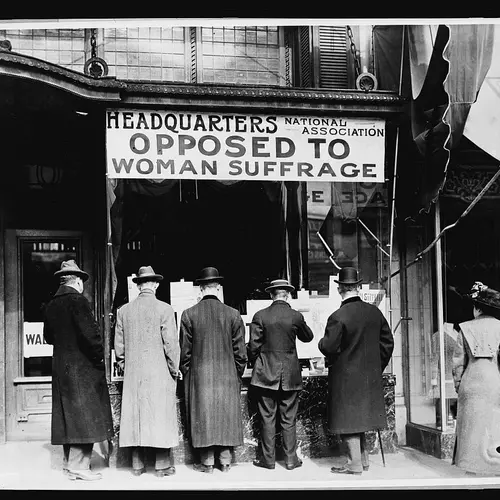

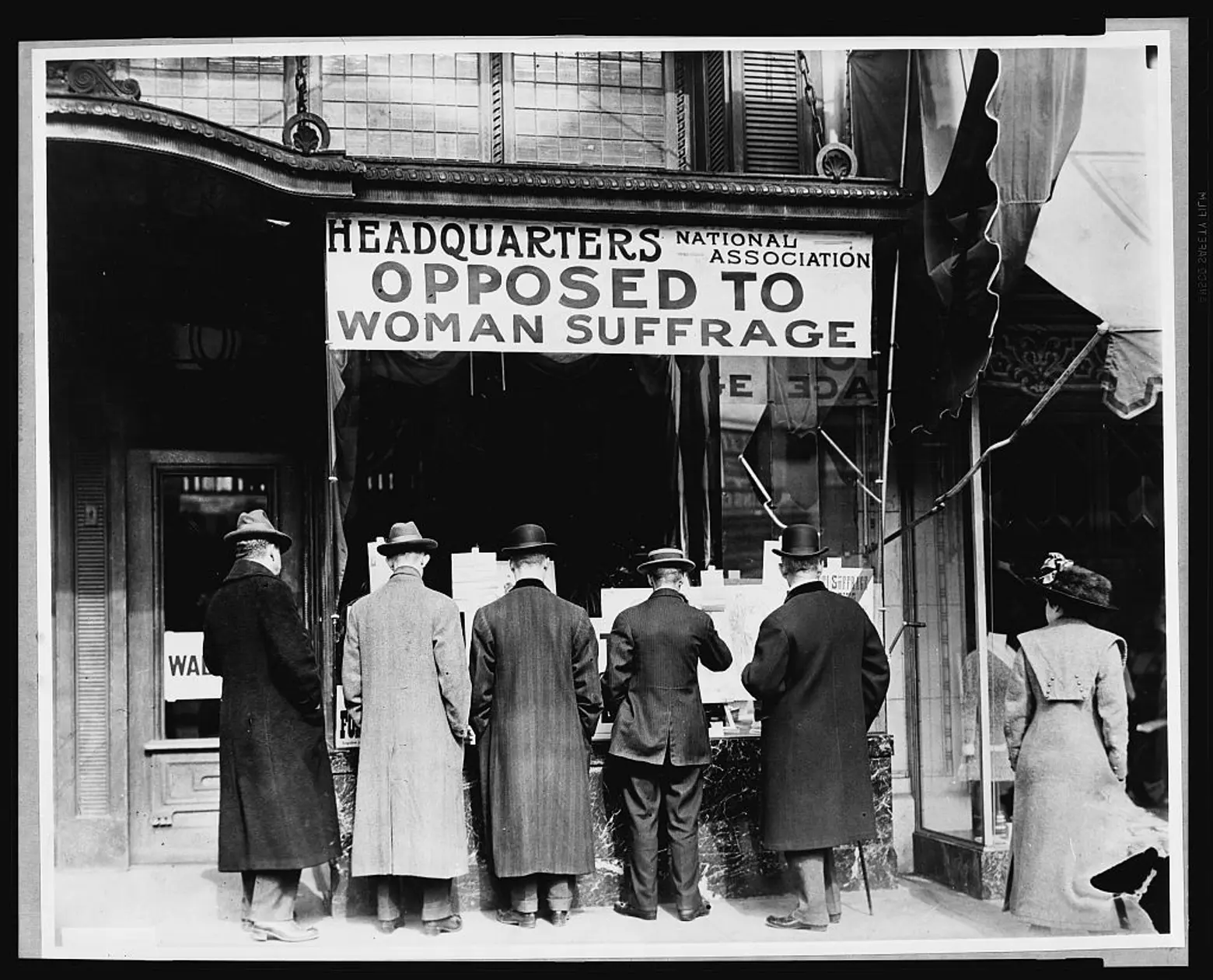

National Anti-Suffrage Association, ca. 1911, via the Library of Congress

Men’s Leaguers persisted in their support until the vote was won despite the fact that to publicly support women was to be subject to public ridicule and condemnation. When 89 members of the League joined thousands of women in the Second Annual New York Suffrage Day Parade in 1911, and marched with them down 5th Avenue, those men were taunted and cat-called by rowdy spectators, who enjoined them to “Hold up your skirts, girls!”

Their staunch support, and serious advocacy, helped inspire other men to support the cause. Laidslaw remarked, “there are many men who inwardly feel the justice of equal suffrage, but who are not ready to acknowledge it publicly, unless backed by numbers. There are other men who are not even ready to give the subject consideration until they see that a large number of men are willing to be counted in favor of it.” He was right. With vocal, public participation from a significant number of prominent men, The Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage grew to include thousands of members in chapters across thirty-five states.

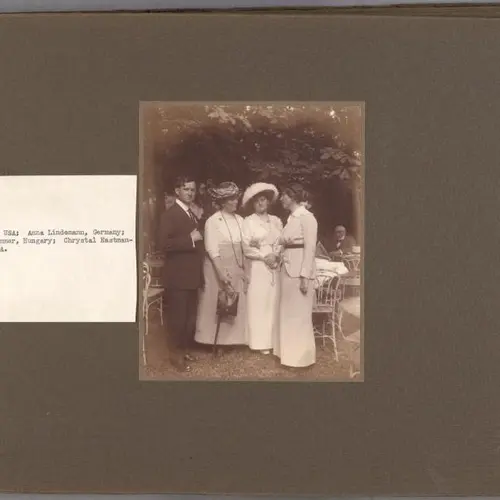

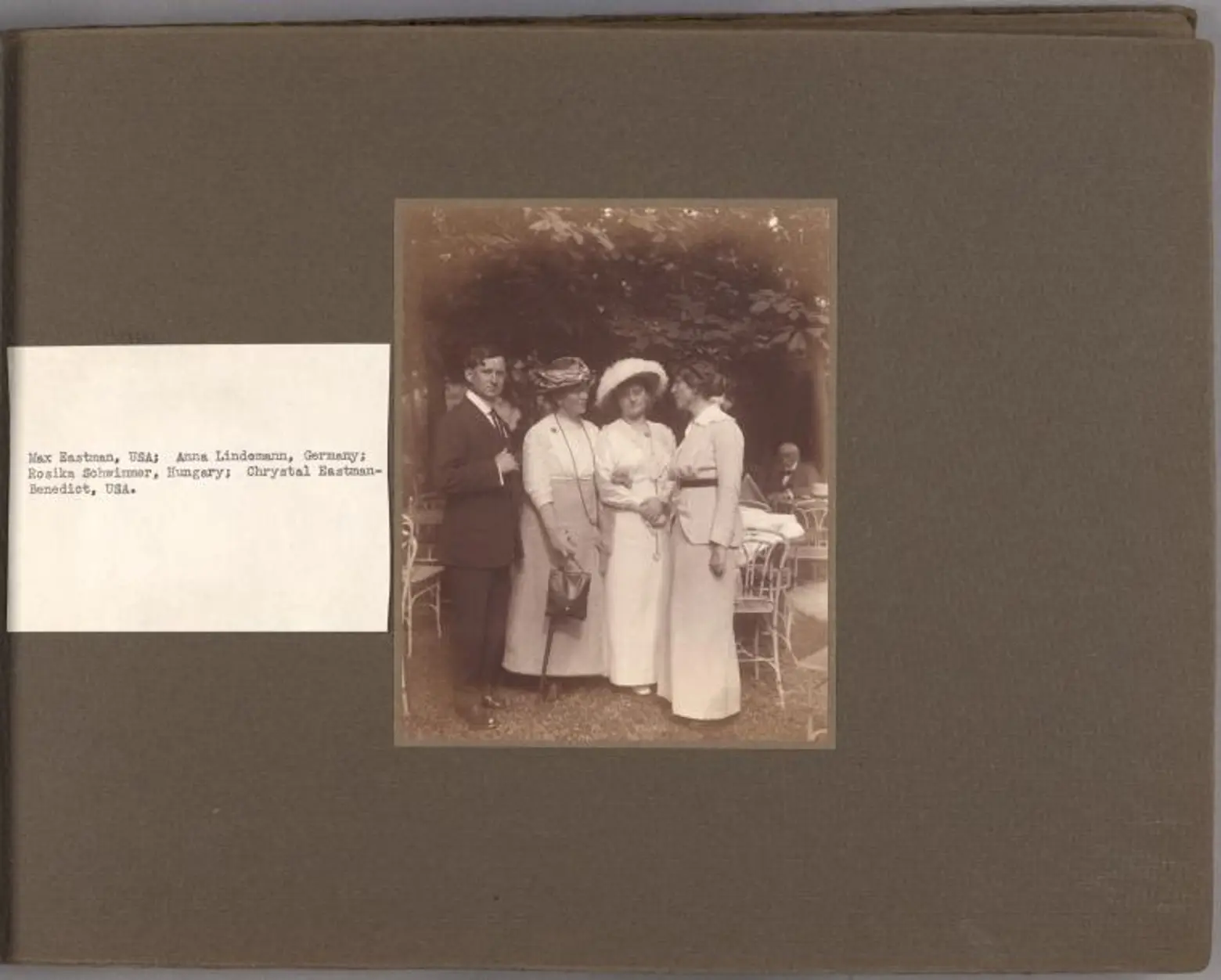

Max Eastman with Anna Lindemann, Rosika Schwimmer and Crystal Eastman, 1913, via NYPL

Women also induced men to join. Many of the League’s leaders were part of pro-suffrage social circles, and were proud “Suffrage Husbands,” who worked alongside wives active in the movement. For example, Max Eastman’s sister, Crystal, and his wife, Ida Rauh, were passionate suffragists, and graduates of NYU Law School. Ida Rauh chaired the legislative committee of the Women’s Trade Union League, and Crystal Eastman was active on all progressive fronts: she became the first female commissioner in New York State; helped implement the first workers’ compensation legislation in the country; cofounded organizations including the ACLU, the Congressional Union for Women’s Suffrage and the Women’s Peace Party, and was one of four original writers of the Equal Rights Amendment.

Several League members, too, were noted for their work in a variety of other progressive fields. John Foster Peabody was active in the Anti-war movement and in support of Historically Black Colleges and Universities; Oswald Garrison Villard was a co-founder of the American Anti-Imperialist League and the NAACP; Charles Culp Burlingham sat on the New York City Board of Education and served as President of the Welfare Council of New York City. These men, and others who joined them in the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage, saw equal suffrage as “a new outlet in the cause for justice,” which, they understood with clear-eyed foresight, it was their duty to support.

The vote is still an outlet in the cause of justice. You can find your polling place here.

RELATED:

- Brownstones and ballot boxes: The fight for women’s suffrage in Brooklyn

- MAP: Explore the women’s suffrage movement through the lens of NYC landmarks

- Women’s History Month began in New York in 1909 to honor the city’s garment workers’ strike

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.