In 1882, Labor Day originated with a parade held in NYC

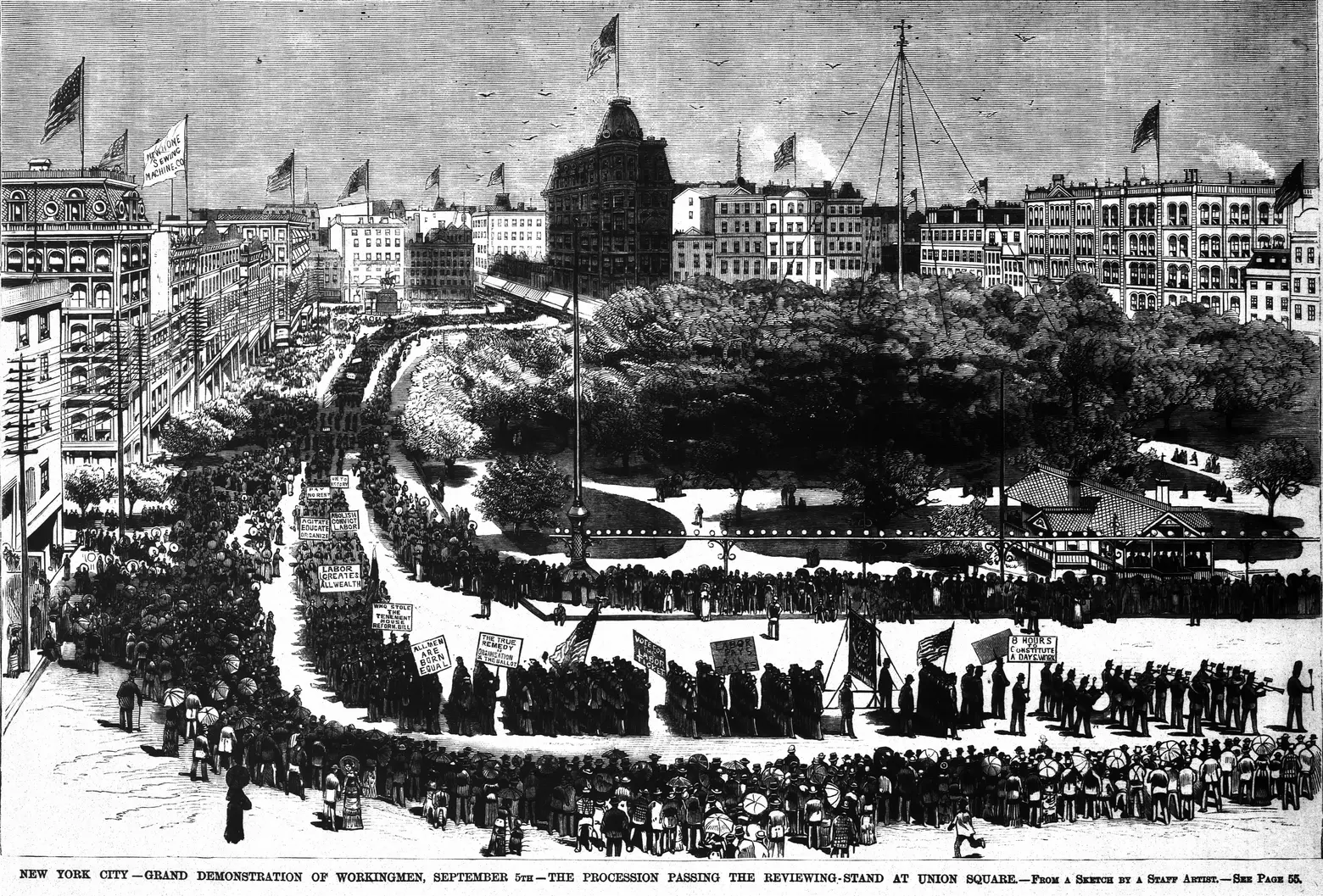

An illustration of the first Labor Day parade, via Wiki Commons

Though Labor Day has been embraced as a national holiday–albeit one many Americans don’t know the history of–it originated right here in New York City as a result of the city’s labor unions fighting for worker’s rights throughout the 1800s. The event was first observed, unofficially, on Tuesday, September 5th, 1882, with thousands marching from City Hall up to Union Square. At the time, the New York Times considered the event to be unremarkable. But 138 years later, we celebrate Labor Day on the first Monday of every September as a tribute to all American workers. It’s also a good opportunity to recognize the hard-won accomplishments of New York unions to secure a better workplace for us today.

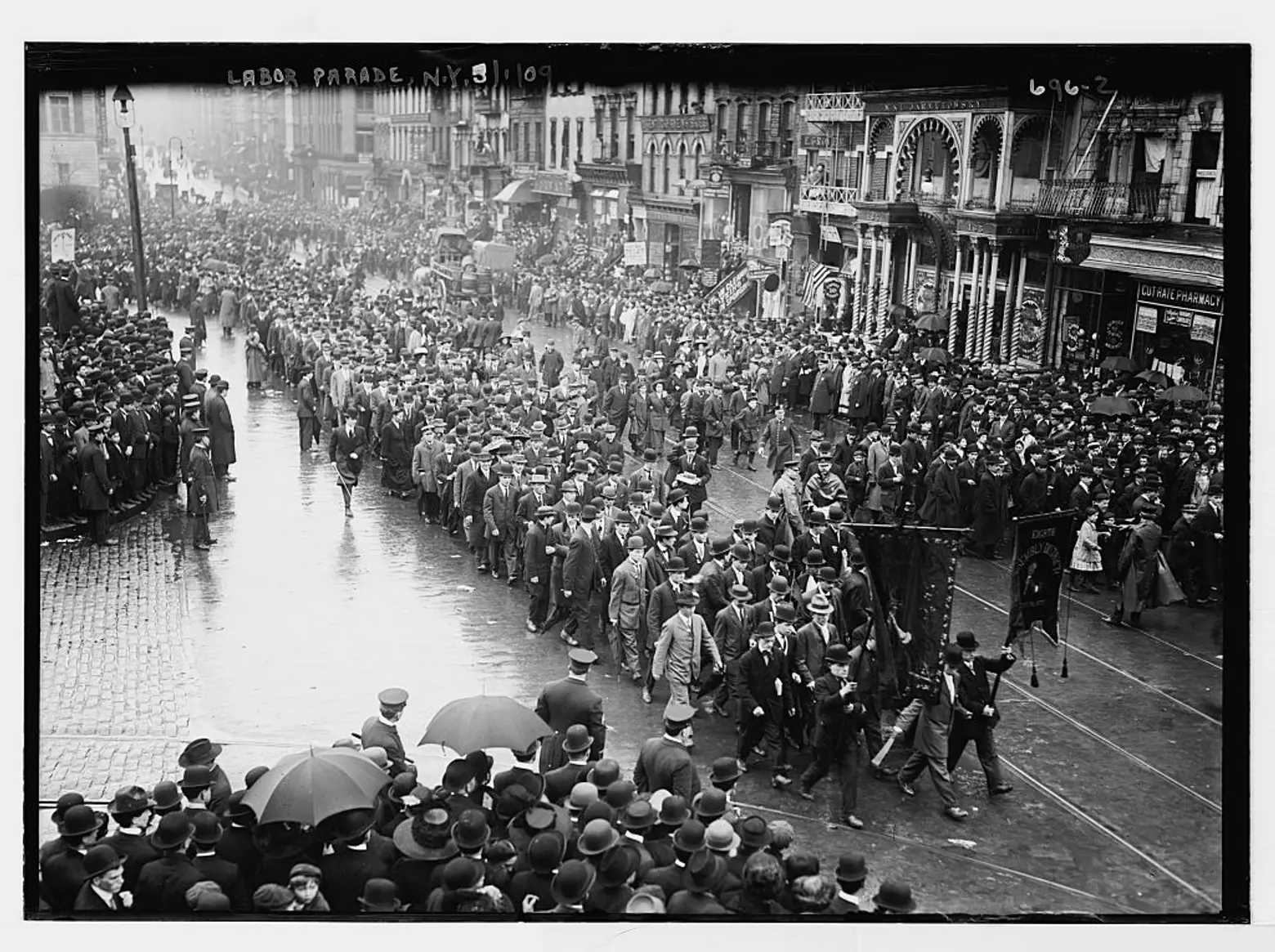

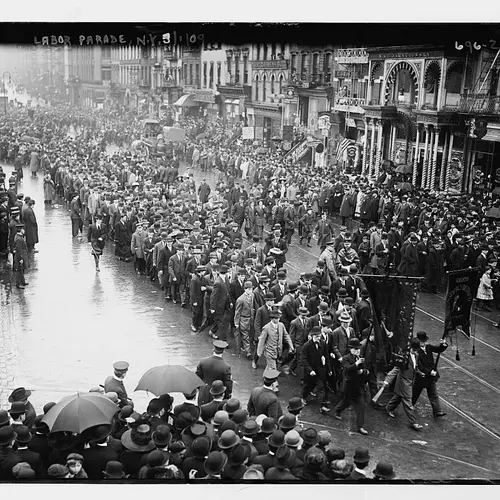

Bain News Service, P. Labor Day parade, marchers, New York. 5/1/09 date created or published later by Bain. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

According to Untapped Cities, the holiday has its roots in a common 19th-century tradition in which laborers held picnics and parades to draw awareness to worker’s rights. Organized unions emerged from there, and New York City became a hotbed for labor activists by the Industrial Revolution of the 1880s.

Back then, laborers were fighting against low wages, unfair hours, child labor, and unsafe working environments. (Most workers at the time worked six days a week, 10 or 12 hours a day, and Sunday was the only day off. There were no paid vacations, no sick days, and very few breaks during a day.) Two labor groups, the Knights of Labor and the Tailor’s Union, established a city-wide trade consortium–known as the Central Labor Union of New York, Brooklyn, and Jersey City, or the CLU–in January of 1882 to promote similar goals. They called for things like fair wages, an eight-hour workday, and an end to child labor. The group also proposed that for one day a year, the country celebrate American workers with parades and celebrations. The CLU went ahead and organized the first parade for September 5th of that year.

According to Brownstoner, two different men within the labor movement were credited for the parade. Matthew Maguire, a machinist, first proposed a holiday and parade in 1882. He was the secretary of the CLU. But that same year, Peter J. McGuire, cofounder of the American Federation of Labor, also proposed a parade. The debate between the original founder of Labor Day was never settled, though Matthew Maguire usually gets the credit.

The parade began outside City Hall, with the CLU advertising it as a display of the “strength and esprit de corps of the trade and labor organizations.” It was important to the event that the men gave up a day’s pay to partake in the festivities. And they did arrive in droves, with banners and signs with slogans like “NO MONEY MONOPOLY” and “LABOR BUILT THIS REPUBLIC AND LABOR SHALL RULE IT.”

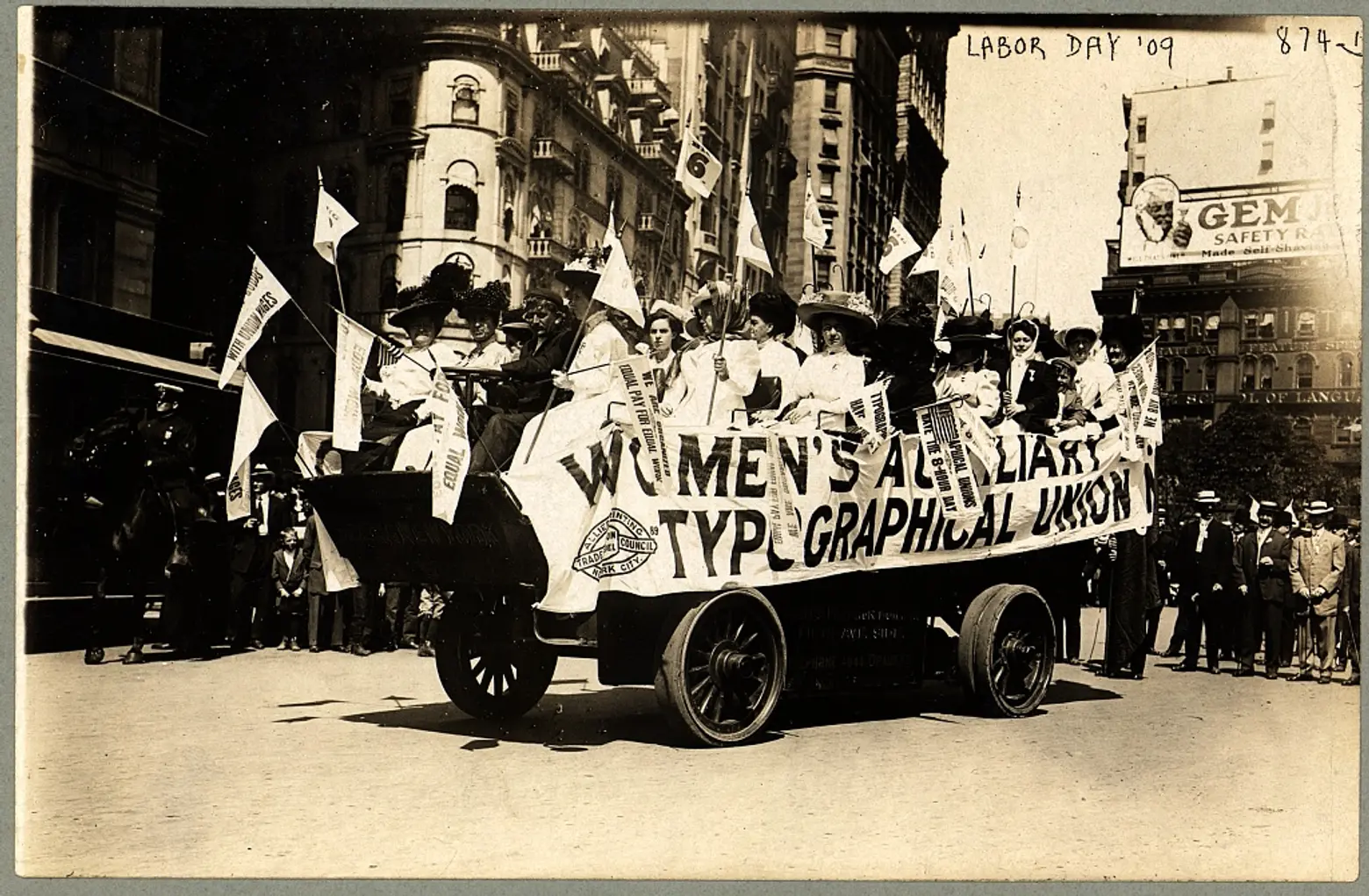

No drinking was allowed at the parade, which featured everyone from the Jewelers Union of Newark to the typographical union, which was known as The Big Six. Along the route, which passed Canal Street on its way to Union Square, hundreds of seamstresses hung out the windows cheering the procession, blowing kisses and waving their handkerchiefs. It’s said as many as 20,000 men marched that day.

The party after the marchers hit Union Square was celebratory, according to the New York history book Gotham. Here’s a passage from the book:

Finally, after passing by a reviewing stand filled with labor dignitaries, the participants adjourned, via the elevated, to an uptown picnic at Elm Park. There they danced to jigs by Irish fiddlers and pipers and were serenaded by the Bavarian Mountain Singers while the flags of Ireland, Germany, France, and the USA flapped in the autumn air.

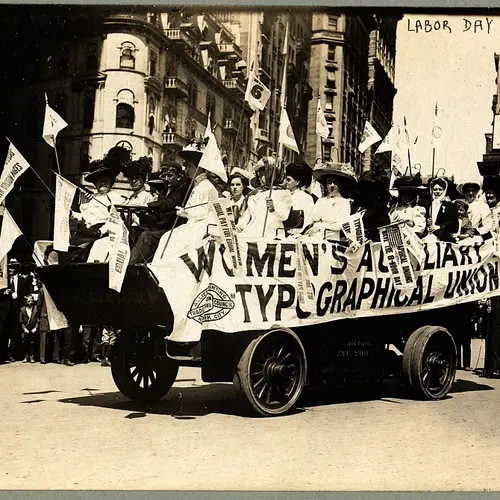

Labor Day parade float in New York City, 1909, via Library of Congress

Labor Day parade float in New York City, 1909, via Library of Congress

Labor parades began in other cities around the county, and for a while, the day was known as “the workingman’s holiday.” By 1886, several cities had an annual parade, with legislation in the works to make the day a state holiday. Though New York was the first state to introduce a bill to make the holiday official, Oregon was the first to actually pass it as law in 1887. New York quickly followed suit that same year, as did New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Colorado.

Labor unions, of course, went on to secure rights like the eight-hour workday, collective bargaining, health insurance, retirement funds, and better wages. These days, the holiday is better known as a marker to the end of summer than a celebration of the working class. But it’s a nice reminder of such hard-fought battles, which brought accomplishments that now define the American workplace, took root in New York.

RELATED:

- Remembering the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire and the women who fought for labor reform

- The history of Brooklyn’s Caribbean Carnival, the most colorful event in New York City

- A 15-year-old Greenwich Village student inspired the hit song ‘Summer in the City’

Editor’s Note: This story was originally published on August 30, 2019.

Get Insider Updates with Our Newsletter!

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

Journey from Freedom to Slavery, Serfdom, Forced Labor, and Involuntary Servitude:

While Labor Movement made much progress to defend rights of unskilled, hourly wage earners, US Congress over the years promulgated Laws that created rules and regulations that totally compromise the dignity of man who spends his lifetime performing painful toil on the US soil.

For example, all people who perform labor spend hours of their life experiencing the aging process as per Natural Law. Hourly wage earners cannot avoid the experience of consequences of old age. As of today, there are millions of workers who pay into the system through provisions of FICA payroll deductions are not assured of receiving monthly retirement income benefit after attaining full retirement age which currently stands at 67-Years. Such unfair, and unjust treatment of unskilled workers is made possible by US President Bill Clinton who signed Public Law 104-193. on August 22, 1996. It is not illegal if hourly wage earners have to choose between Work and Death as Retirement is not an option sanctioned by the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act or PRWORA{refer to Section 401(b)(2) and 431(b)}.