INTERVIEW: Architect Morris Adjmi talks standing out while fitting in and organizing art exhibits

In architect Morris Adjmi’s new book, “A Grid and a Conversation,” he describes his ongoing conversation between context and design. On any project, Adjmi balances three factors: standing out while fitting in, respecting history while not being frozen in time, and creating “ambient” architecture while gaining popularity. 6sqft sat down with Adjmi to find out more about his work philosophy, art exhibits, love of Shaker design, and awesome opening night parties with custom-made drinks.

The Wythe Hotel in Williamsburg

The Wythe Hotel in Williamsburg

In your book, you talk a lot about both standing out and fitting in. I think that’s a delicate balance you handle incredibly well. Can you explain how that dichotomy and how it fits together in your work?

It’s a balancing act we try to maintain. Potentially, there is justification for making a building that says, “Hey, I’m here,” and makes a loud statement. But we can’t build cities by doing that all of the time. When we work on projects, we try to balance how present a building is, or how loud the statement is, with it playing nice with its neighbors. That’s the space we like to occupy. Each project has its own needs and by virtue of its location or context or the history of the neighborhood, we can justify different levels of visibility. So different projects we’ve worked on have expressed themselves in a more exuberant way.

837 Washington Street. Photo: Timothy Schenck, Alexander Severin, Matthew Williams

837 Washington Street. Photo: Timothy Schenck, Alexander Severin, Matthew Williams

A good example of the exuberant side is the Samsung building at 837 Washington. It’s a building that I think is very respectful to its context and to its immediate neighbor, which is the building I like to describe as sharing a site with. I look at the new piece as being more of co-sharing of the space with the existing building. I try to look at that as less of an addition and more of two things playing off each other and working together on the same space.

There were some previous proposals for that building. The first was to tear the existing building down but the Landmarks Commission deemed it a contributing building because it was purpose-built as a meat packing facility. Even though it doesn’t look like a special building, it is special in the context because it was one of the few buildings that was really built for that purpose. The others were mostly residential buildings that were shaved down because people wanted to live above them so that really reflected a specific time frame. It was the end of the new construction in that area and that happened in the ’30s, around the Depression, so there wasn’t a lot of activity there.

837 Washington Street. Photo: Timothy Schenck, Alexander Severin, Matthew Williams

837 Washington Street. Photo: Timothy Schenck, Alexander Severin, Matthew Williams

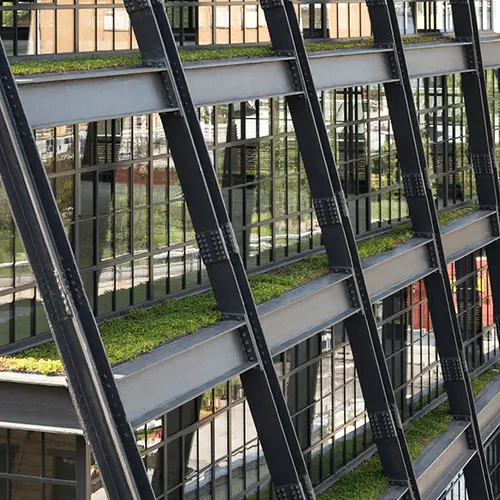

When we were looking at how could we put more area on that site and add on to that building, we tried to allow the existing building to breathe and have its own presence and identity, [which we did] by setting the building back and torquing and twisting it. The window pattern came from the existing punched openings; we used the same proportions and light cut of those windows for the factory-style windows that you see on the [new] building. The metal is a robust structure that’s actually supporting the building and draws from the High Line. Even though that isn’t part of the historic district, it really is the context being right across the street. The layering of the planting beds also has a reference to the industrial landscape of High Line.

The twisting came from initial studies when we were trying to figure out how to create separate identities for the new part and the old part. One thing that started to make sense was the way the twisting was referencing what was happening on the street. If you look at the street grid above 14th Street, it’s the Commissioner’s Plan’s that we know, but that didn’t come until 1811. Before that, you had the Greenwich Village grid and down here [the Financial District], a haphazard assembly of streets. The ownership of the streets went around and so right at 14th street is where it used to end. In the Gansevoort Market/Meatpacking District, you see all of these spaces that reflect the collision of a regular grid and irregular grid, the change from the orthogonal to less than organized grid.

30 East 31st Street; Rendering: Ekstein Development Group/Morris Adjmi Architects

30 East 31st Street; Rendering: Ekstein Development Group/Morris Adjmi Architects

Regarding my work becoming recognizable, a lot of times a client will say, “Can you do one of those for me.” I answer, “No but we can do something that works the same way.” We’ve got a lot of projects that have I-beams, steel, or factory windows, which is a recognizable style of what we’re doing with the imagery being consistent. But if you look at what we’re doing on 79th Street or this tower on 31st Street, it’s a very different aesthetic but the process and the approach to creating those projects are the same. On 31st Street, we’re drawing from some of the gothic architecture in the neighborhood but also trying to create a dialog with other towers, whether it’s the Empire State Building or the Chrysler Building. Those three buildings speak well to each other because they have these recognizable tops and become something special in the skyline as opposed to another glass tower that could be anywhere.

408 Greenwich Street uses unadorned terracotta arches as a modern interpretation of the traditional masonry buildings found throughout its Tribeca neighborhood. Image: Jimi Billingsley.

408 Greenwich Street uses unadorned terracotta arches as a modern interpretation of the traditional masonry buildings found throughout its Tribeca neighborhood. Image: Jimi Billingsley.

Another big topic in the book is the importance of respecting history but that things are not frozen in time. You take historic things and make new out of them. Can you tell us more about that?

That has been the story with architecture from the beginning. The modern movement questioned that, but I think if you look closely, you’ll see that history definitely influenced a lot of those projects. If you look at AEG, works by Gropius, even Mies looking at classical temples. But the language changed and that’s part of what we should do. We should question forms and materials and we have conditions or considerations, whether it’s sustainability or things that could change as we are getting more civilized. I don’t like the hyper-referential postmodern aesthetic. I’m not trying to appropriate forms, I’m trying to appropriate a way of looking at architecture that is a development of what has happened in history but speaks to our time. It doesn’t mean you can’t use style to connect to history, but it’s not always a literal usage of those elements.

Interior rendering of The Schumacher condo conversion in Noho. Photo: Matthew Williams, Evan Joseph.

Interior rendering of The Schumacher condo conversion in Noho. Photo: Matthew Williams, Evan Joseph.

It seems you often use shaker cabinetry when you do kitchens. Why?

I’ve been a fan of shaker design since I first saw a show at the Whitney probably about 30 years ago. I read the book “Seven American Utopias,” which talked about all the different utopian societies. I think there is a purity of their design, a simplicity and a modernity at the same time. Those are all things that we try to strive to do. There is also an honesty about their design. They are innovative but not to the point where it’s just innovation for innovation’s sake. It is very measured.Those are qualities we try to imbue in the work we do.

The Aldo Rossi show. Photo: Alexander Severin.

The Aldo Rossi show. Photo: Alexander Severin.

I am very interested in your art collection. Tell me more about it.

That came about as a way to keep the environment fresh in the office. When we were moving here two and a half years ago, there were a lot of photographs and works on the walls that had been up for years. I was like, “How could we have left this up for so long? We certainly can’t take it down and go put it up in our brand new office.” So what could we do? I have a collection of Aldo Rossi drawings and said, “Why don’t we put those up?” But I also didn’t want that to become the static statement. So I came up with this idea to do a rotating series of exhibitions, not even realizing how much of a production it turned out to be. The idea was to change up the environment and expose the staff to different works that would inspire us.

The Van Arkel exhibit. Photo: Alexander Severin

The Van Arkel exhibit. Photo: Alexander Severin

One additional plus is that a number of our clients have bought pieces. One of the artists, Matthias Van Arkel, who does silicone work, had a particular piece in the lobby. We were meeting with a client about artists and she said, “Why can’t I just get one of those?” and we replied, “You can.” So we put her in touch with the artist and they decided to buy a piece and put it in a lobby of a building we were doing for them in Williamsburg.

The Starr exhibit. Photo: Etienne Frossard

The Starr exhibit. Photo: Etienne Frossard

Another artist, Lyle Starr, who is a friend of mine, did a series of 70 drawings. We had a price list that was something like $1,500 each, or, if you buy three it was $1,200 each. I was showing a client around and he said, “What if I buy all of them?” So I put him in touch with the artist and he bought them. I think he is going to mount those in one of the buildings we are working on right now.

The opening-night party of the Lyle Starr exhibit. Photo: Morris Adjmi Architects

The opening-night party of the Lyle Starr exhibit. Photo: Morris Adjmi Architects

How do you choose the art and the artists?

It’s been organic. Matthias was someone we’d worked with. He did an elevator vestibule installation in a project we did. Some were friends. After the third show, we did a group show. We sent out an email to everyone in the office and said we’re doing a group show for friends and family and asked them to submit work. We made the theme “space.” Some people interpreted that as a rocket ship and others as people in space. It was very loose. We had a jury, we assembled all of the work, and we decided which ones worked well together. Lyle helps with all of our installations. We did this Forgery show which is up now. I had read an article about artists in California who use masterworks as a way to learn how to paint.

And then–the opening parties. We started out with the Aldo drawings. I had done a “cocktails and conversation” at the AIA. I met this mixologist, Toby Cecchini, who has a bar called “Long Island” in Brooklyn. I said, “We want to do a special cocktail in Aldo’s honor.” So he made two Italian-inspired cocktails. That started the process. Now, we have a special cocktail or cocktails at every event. One of the craziest ones was for Matthias’ show, we did mini-cubes that looked his works but they were jello shots. For the Forgery show, they made three drinks that looked like something but were something else. In a little coke bottle, they had boulevardier. In a little Miller pony, they did sparkling wine with a little food coloring. And then the last one was a white Russian in a Greek, to-go coffee cup. They were dispensing them from a coffee urn. And the food looked like a still life.

The next exhibit is going to be a photographer from Holland. I just started following her on Instagram and we reached out to her. We’ve had seven shows so far. We’re trying to keep it fresh. I’d love to plant a whole garden in the office, like the mudroom at the Walter de Maria but not so muddy.

+++

RELATED:

- INTERVIEW: LOT-EK’s Giuseppe Lignano talks sustainability and shipping container architecture

- INTERVIEW: Architect Lee H. Skolnick on designing New York City’s 9/11 Tribute Museum

- INTERVIEW: Architect Rick Cook on the legacy of COOKFOX’s sustainable design in NYC

All photos courtesy of Morris Adjmi Architects. Lead image: 837 Washington Street via Timothy Schenck, Alexander Severin, Matthew Williams.