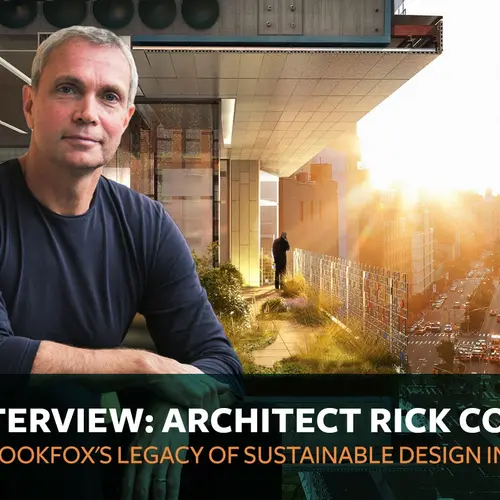

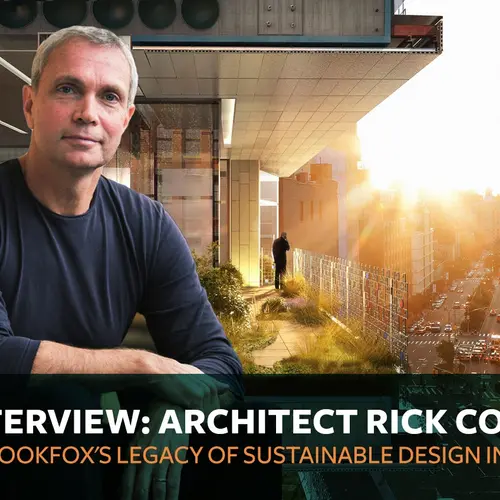

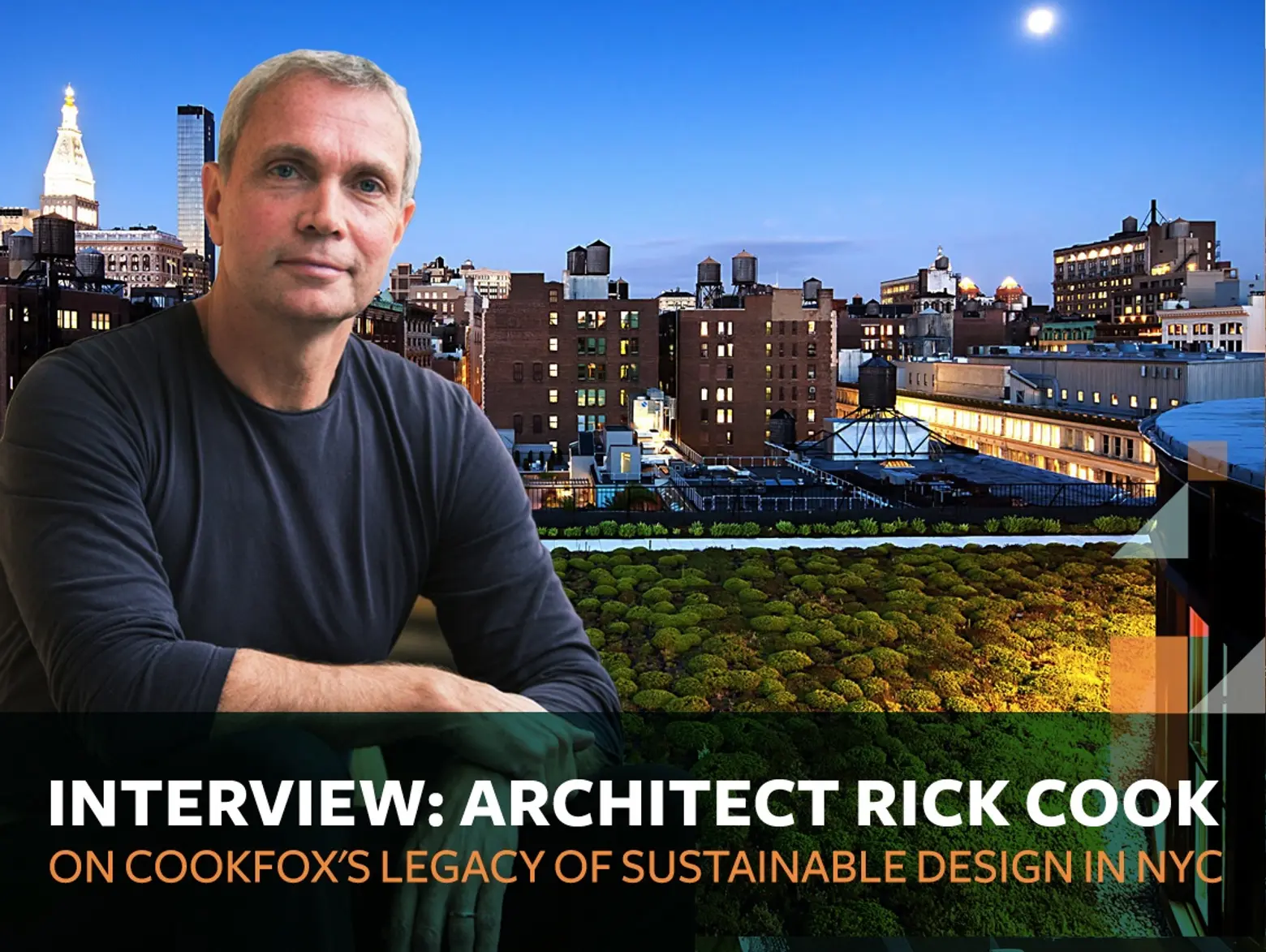

INTERVIEW: Architect Rick Cook on the legacy of COOKFOX’s sustainable design in NYC

Since its founding in 1990, COOKFOX Architects has become one of the most recognized names in New York City real estate. In the firm’s early days, founding partner Rick Cook found a niche in historically-sensitive building design, looking for opportunities to “[fill] in the missing voids of the streetscape,” as he put it. After teaming up with Bob Fox in 2003, the pair worked to establish COOKFOX as an expert in both contextual and sustainable development. They designed the first LEED Platinum skyscraper in New York City with the Durst family, the Bank of America Tower, then took on a number of projects with the goal of designing healthier workplaces. The firm also got attention for its work in landmarks districts, winning AIA-New York State awards for its mixed-use development at 401 West 14th Street (better known as the Apple store) and its revamp of the the Stephen Sondheim Theatre. (The firm also made it the first LEED-certified theater in the city.)

More recently, the firm has taken on projects that promise to redefine entire sections of New York City. They designed both 550 Vanderbilt and 535 Carlton, two Brooklyn residential buildings tasked with tying the massive Pacific Park development to neighboring Prospect Heights. The firm also designed the City Point project, which is transforming Downtown Brooklyn’s Fulton Street with retail, affordable and market-rate housing, office space and a food hall.

6sqft spoke with Rick Cook about the evolution of his firm into a major presence in New York real estate, and why the values of sustainability and good design are more important now than ever. Rick also shared his thoughts on how architects can address the city’s affordable housing crisis, some of his most memorable projects, and why gardens and green space consistently surprise him.

What were your early design goals when you founded the firm?

Rick: I founded the firm in 1990 and a lot of our early work was focused on filling in the missing voids of the streetscape—a lot of work in landmark districts. That work grew and we stumbled on the historic preservation movement and the environmental movement, which were really sister ethics in that they were both interested in these beautiful resources we inherent and how we leave them for the next generation.

That work resulted in a partnership with my former mentor, Bob Fox, in 2003. Immediately after becoming partners, we started working on One Bryant Park, the Bank of America Tower. It was the first LEED Platinum Skyscraper, with the Durst family and the Bank of America as joint partners. It was an amazing amount of fun and timely because the world was really getting interested in sustainability and what we were doing. That led to almost all the other work since then.

What was the attitude around LEED when you took on the One Bryant Park project?

Rick: In 2003 it was still pretty new and One Bryant Park was the first LEED Platinum skyscraper. We also built our own office, which was the first LEED Platinum certification of any kind in New York. In the early days of LEED, it was really about building performance with the goal of making buildings better for the planet. What we discovered was when we made buildings better for the planet, we made buildings better for the people who inhabit them. That transitioned the work into human health and wellness—sometimes described as productivity.

One Bryant Park, courtesy COOKFOX

One Bryant Park, courtesy COOKFOX

Was it ever a struggle to convince developers that sustainability was worth taking a risk on?

Rick: We were blessed with the fact that the Durst’s were a second generation green skyscraper developer—they had also done the building 4 Times Square. They already learned air quality was extremely important and had a great experience with that project. One Bryant Park was really the jumping-off point from everything they learned from Four Times Square and see how much further we could go.

We did not chase LEED points. We set out to explore every good technology that would make a fundamentally better building. When we were done, we ended up LEED Platinum.

What have been the biggest attitude shifts toward LEED and sustainability in the real estate industry?

Rick: Within the development industry, we would always get the question “How much more does this LEED stuff cost?” Then a younger generation got involved, and we realized the impact the build environment had on the planet and carbon production. We started to see how much an impact we could make on these buildings.

Then, the number one question became, “If we now know this, why aren’t all buildings done this way?” or “I live in a co-op in Brooklyn, what can I do?” Phase three seems to be that it’s become a new definition of quality. If thoughtful people are trying to do a good job, of course you would pursue a LEED rating and the best building you possibly could. It’s become much more accepted.

You’ve been working on 535 Carlton and 550 Vanderbilt, part of the greater Atlantic Yards redevelopment. It’s a project with a lot of history, and will soon be a whole new neighborhood in Brooklyn. What’s that project been like?

550 Vanderbilt, photo by Max Touhey

550 Vanderbilt, photo by Max Touhey

Rick: We didn’t have an intention of being involved with the project formerly known as Atlantic Yards [now Pacific Park], but we liked the key people we worked with at Forest City Ratner [the developer] on a proposal for Seward Park. I saw how important the sites of 535 Carlton and 550 Vanderbilt would be to the project… they could speak a language that could transition into, and be a part of, the adjoining neighborhood. Not something separate, not a new neighborhood, but an extension to the existent neighborhood.

One of the first things we did—we didn’t want to call the sites by a letter/number designation again. These would be real buildings on real streets.

535 Carlton, photo by Max Touhey

535 Carlton, photo by Max Touhey

What inspired the design of the buildings?

Rick: There’s no question 535 Carlton was inspired primarily by the shadow and earthy textures of Carlton Place. We wanted to be a good neighbor to that street. 550 Vanderbilt, on the other side and off a wider boulevard, was inspired by that location. The lighter pallet was inspired by the nearby cathedral of St. Joe’s. Both these buildings were site-specific to the context that existed, but make a transition into the context that would exist when Pacific Street becomes Pacific Park.

Prospect Heights street leads to Pacific Park, photo by Max Touhey

Prospect Heights street leads to Pacific Park, photo by Max Touhey

Your work has addressed the need for affordable housing in NYC. How do you view the architect’s role in our current affordability crisis?

Rick: Architects passionate about their work need to be passionate about bringing that same quality to projects for formerly homeless supportive housing, or affordability across wide ranges, or market-rate work. I would encourage everyone to try and bring the care, thought, and passion they do to the field of affordable housing. We believe there should be daylight and views of the park for every resident, so we organized every elevator lobby has a window out to Pacific Park. We made a communal roof on the ninth floor so everyone would have an urban agricultural component.

What have been some unique projects in that the firm could address affordability?

Rick: One project the firm is very proud of is a building called the Hegeman, in Brownsville, Brooklyn, for Breaking Ground. It’s supportive housing for the formerly homeless. We brought daylight into the building and the supportive services, which had historically been in the basement. We tried to bring light, connection and nature to all the residents. On our Earth Day volunteer day we went back to plant gardens.

Then there’s the City Point project; we did the City Tower for Brodsky, the affordable housing component and the big retail center which now has the Dekalb Market. An extremely diverse mixed-use project in Downtown Brooklyn. Same thought with the affordable housing component, there’s daylight in the corridors and urban agriculture on the roof.

What’s been most surprising as the city, particularly Brooklyn, has changed so much and the firm has grown alongside it?

Rick: How our expectations are constantly exceeded when we design with gardens, and therefore nature, in our lives. We just moved into our new studio on 57th Street and have two big terraces we planted. Every day I’m amazed how quickly it changes, how rich and varied a garden is.

As much as we preach it, when we are given the opportunity to plant a garden—oftentimes in green roofs or urban agriculture—every single time we’ve done it, it’s exceeded our wildest expectations.

COOKFOX’s office terrace, courtesy COOKFOX

COOKFOX’s office terrace, courtesy COOKFOX

Any specific projects we should look forward to from the firm?

Rick: I love them all, but the one close to my heart is designing the Marymount School of the Future. The school is based on Fifth Avenue, and they purchased a new site on 97th Street. We’re able to really think about how the beautiful buildings they’ve been in have impacted the kind of education, warmth, and community of the school. Now we have the opportunity to design a new school and try to keep that culture.

Marymount School rendering via Campaign for Marymount

Marymount School rendering via Campaign for Marymount

From the ground-up, we’re thinking about spaces to train our future leaders. Now, we design schools where every student has this little thing in their pocket with access to all knowledge in the universe. So the teacher in that room is teaching how to learn but isn’t necessarily the authority on knowledge anymore. It’s such an interesting change from how I was educated, and what the role of the school even is.

RELATED: