INTERVIEW: Author Julia Van Haaften on delving into the life of photographer Berenice Abbott

Photographer Berenice Abbott has long captured the imagination of New Yorkers. Her storied career began after fleeing Ohio for Greenwich Village in 1918 and included a stint in Paris taking portraits of 1920s heavyweights. But she is best known for her searing images of New York buildings and street life–her photograph “Nightview, New York,” taken from an upper-floor window of the Empire State Building in 1932, remains one of the most recognized images of the city. Well known is her exchange with a male supervisor, who informed Abbott that “nice girls” don’t go to the Bowery. Her reply: “Buddy, I’m not a nice girl. I’m a photographer… I go anywhere.”

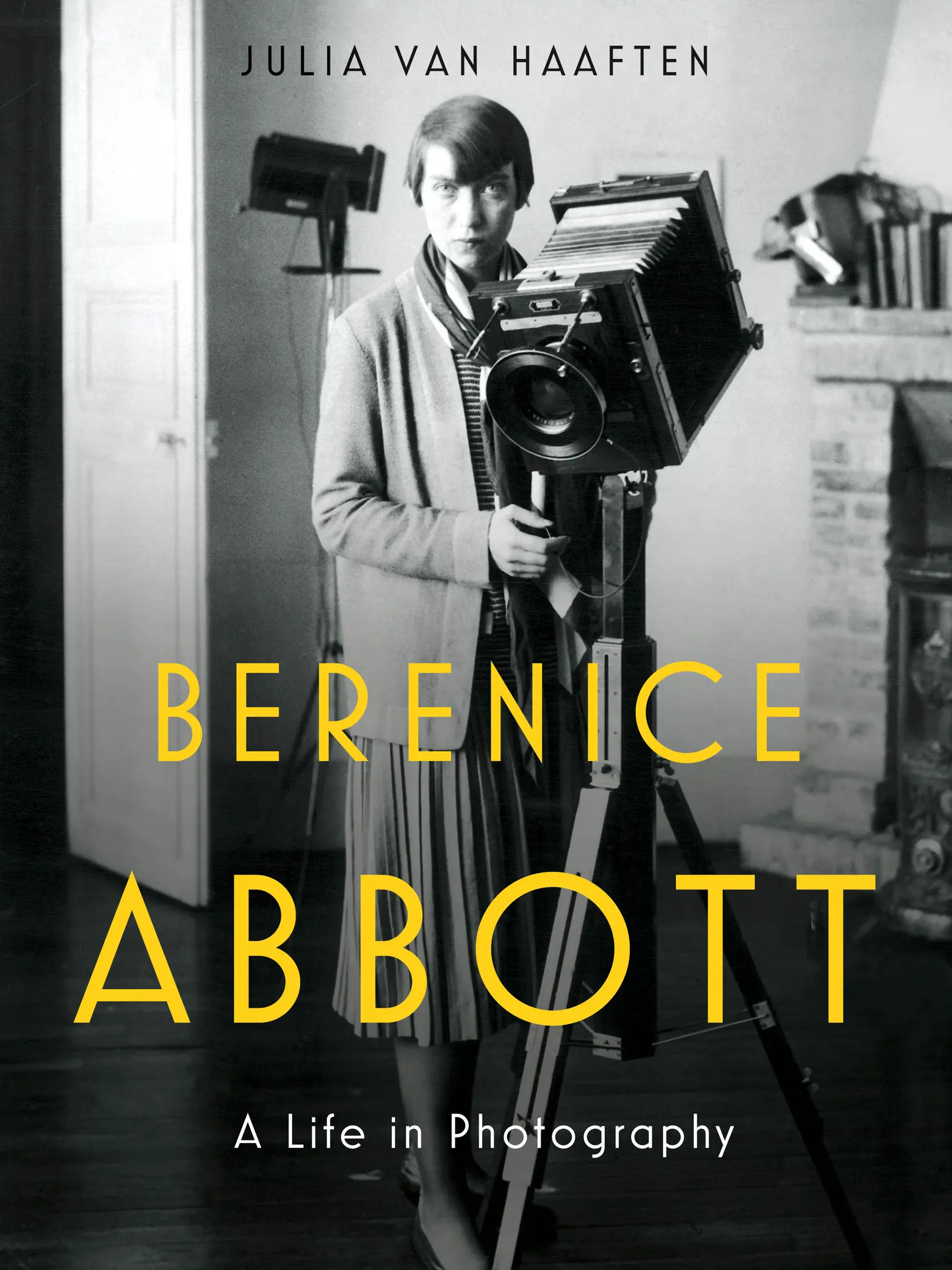

Despite Abbott’s prolific career and fascinating life, there’s never been a biography to capture it all. Until now, with Julia Van Haaften’s work, “Berenice Abbott: A Life in Photography.” Van Haaften is the founding curator of the New York Public Library’s photography collection. She also befriended Abbott, as the photographer approached 90, while curating a retrospective exhibition of her work in the late 1980s. (Abbott passed away in 1991 at the age of 93.)

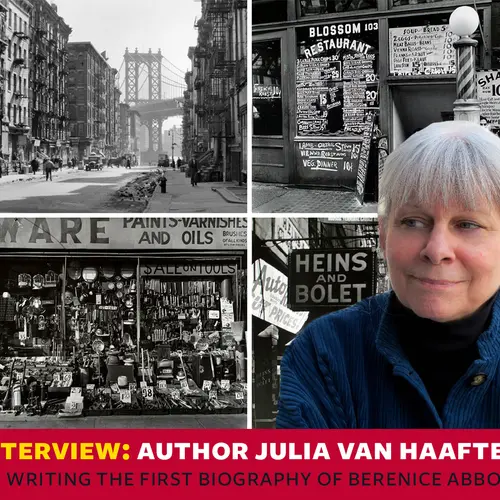

With 6sqft, Van Haaften shares what it was like translating Abbott’s wide-ranging work and life into a biography, and the help she received from Abbott herself. From her favorite stories to her favorite photographs, Van Haaften shows why Abbott’s work has remained such a powerful lens capturing New York City to this day.

What work were you doing before you took on this book?

Julia: I was an art librarian–I graduated from Barnard College with an art history degree. As an art librarian, I discovered there wasn’t a photography section at the New York Public Library. At the same time photography was rising in the art world, there was no specialist on staff for materials acquired at the library for decades. It became my mission internally and a department was formed.

Out of that grew my interest in exhibitions, and I discovered how much the NYPL owned of Berenice Abbott’s “Changing New York.” It fed back onto a passion of mine, photography, which was not part of art history when I went to college in the 1960s. There were a few places that taught photography practice but not necessarily as art. It was taught in journalism or publishing.

Berenice Abbott in New York City in 1979, photograph by Hank O’Neal via Wikipedia

Berenice Abbott in New York City in 1979, photograph by Hank O’Neal via Wikipedia

So what it is about Abbott’s photography that draws you in?

Julia: It’s an interesting balance. It’s both the realism of her city views and the absolute factuality of the pictures, and yet the artistry of the vantage and the subject matter. She would say, “You take pictures of things that are worth taking the trouble about.” That meant, to her, not a political agenda–although something there is meaning underneath the imagery. More she meant something that makes a significant graphic and compositional contribution.

She began taking NYC pictures in the winter of 1929 when she came here back from Paris with a reputation for society portraits on par with Man Ray, who had been her mentor and employer.

She has this incredible, interesting life, and there haven’t been any biographies about her before yours, correct?

Julia: Not really. There had been a biographical essay in a big picture book that came out in the 1980s that she collaborated on with the author, Hank O’Neal. The essay is the story she wanted told about her career; it’s largely her professional practice and accomplishments.

On the other hand, she knew [my book] was in the works, because she and I had done a retrospective exhibition in 1989 that toured. She wasn’t really a collaborator, but she was helpful and interested. She and I hit it off personally. When we talked, she was forthcoming in a way that probably had to do with my being a woman, my being at the library–which she had a deep affection for–and because I didn’t have an agenda beyond admiring her pictures. I thought they were an important, under-celebrated aspect of 20th-century modern art.

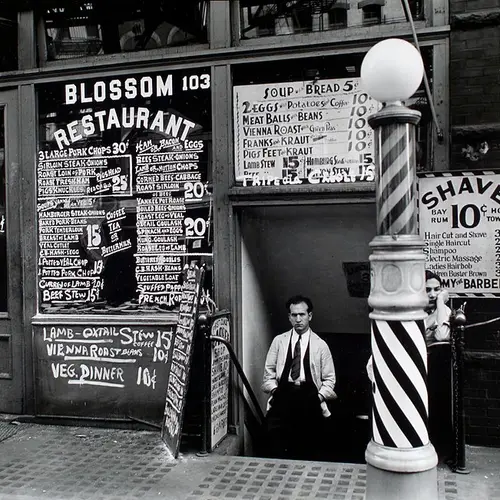

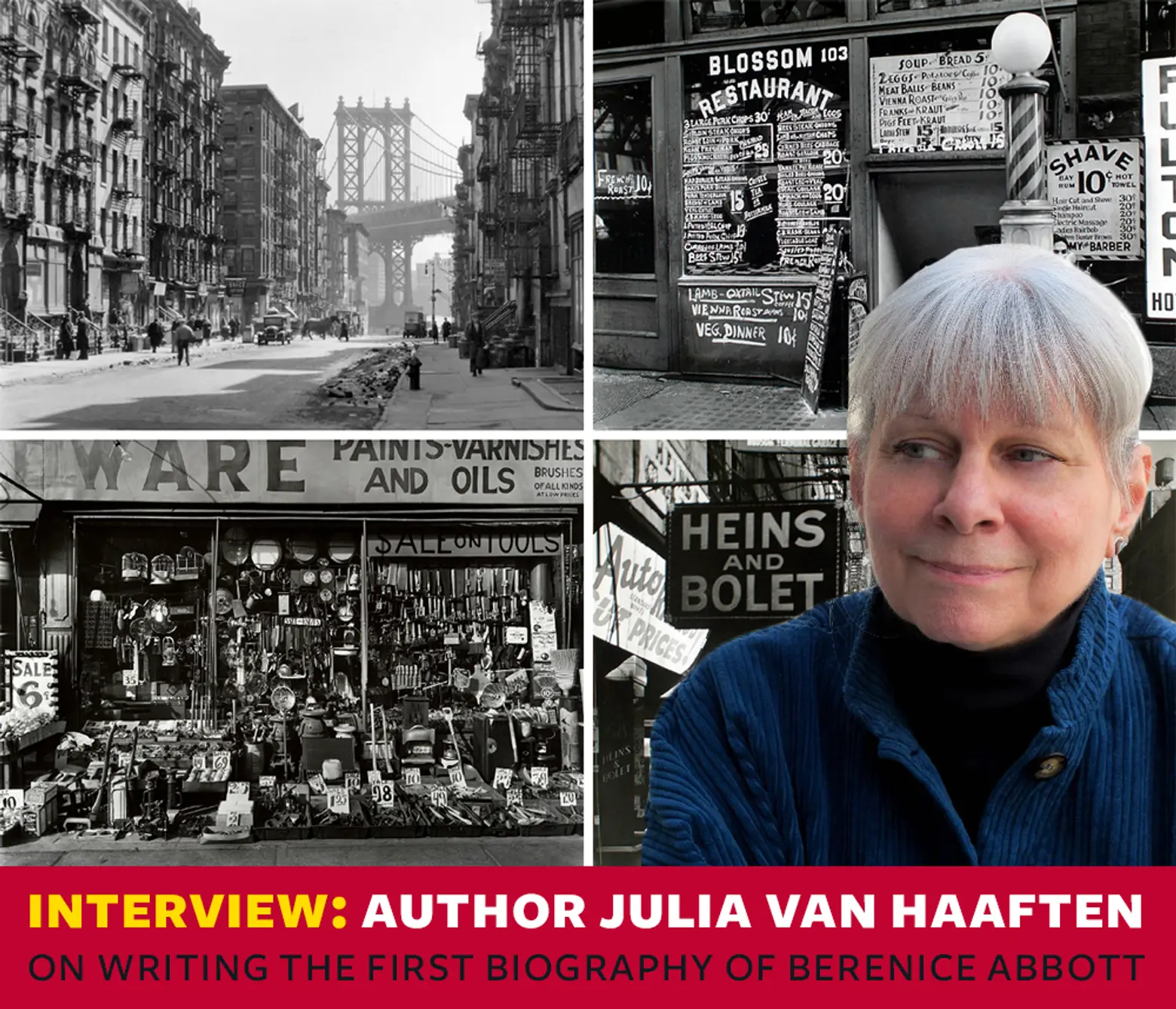

Bowery restaurant photograph for Changing New York, 1935, via Wikipedia

Bowery restaurant photograph for Changing New York, 1935, via Wikipedia

She has a fearlessness, being a female photographer when it wasn’t a common thing to be. Can you talk about that?

Julia: I can talk about it in the sense that she didn’t want to be called a woman anything. That’s what I meant about myself not having an agenda. Obviously, I’m a feminist; obviously, Berenice is too. But it wasn’t the point of our activity. She was an artist, first of all. And I do my work, I don’t see it as an expression of being a woman.

If anything, Berenice and I had a fun relationship because of the contrast between us. I’m a long-married woman, I have two kids Berenice met as children. Personally, I couldn’t be more different than her. But we saw a wavelength of how to get by in the world, on one level, and doing our work and taking it seriously.

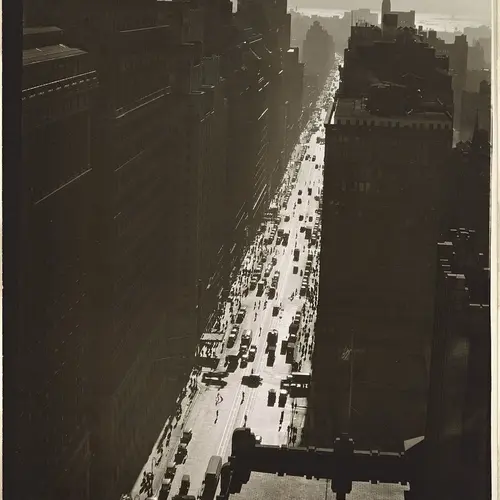

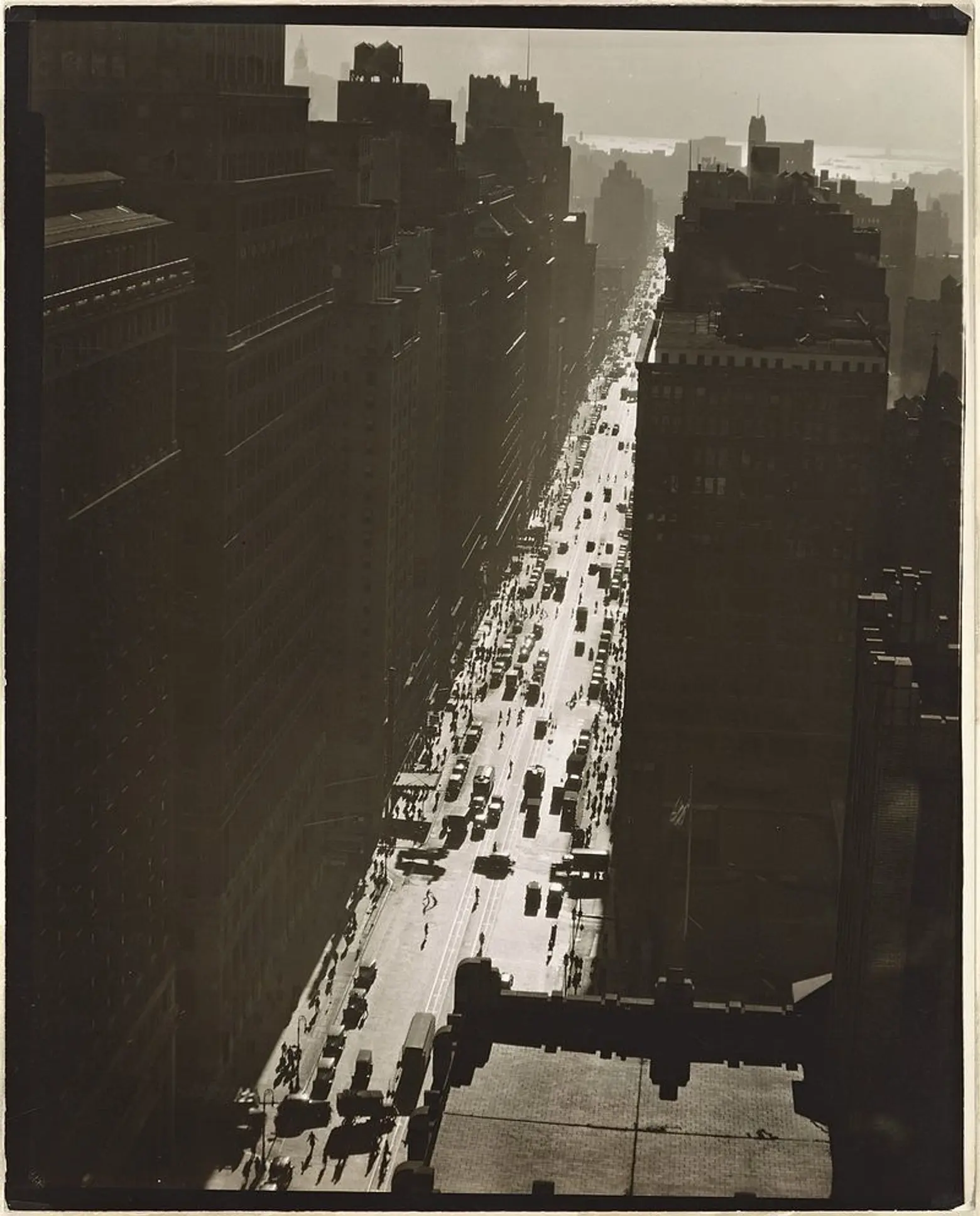

Seventh Avenue, looking south from 35th Street, 1935, via Wikipedia

Seventh Avenue, looking south from 35th Street, 1935, via Wikipedia

And so how did you take her life–her traveling, the breadth of her work–digest it and turn it into a book?

Julia: I began trying to get a handle on the chronology. When I met Berenice, she had just turned 90. So she had codified a lot of her history, and explanation of how things happened, into neat little packets of sequence. Rather than accept it at face value, I figured there’s a lot of fits and starts–it isn’t one smooth flow. She didn’t really know what happened in her own family, her mother’s or father’s story. So it took some genealogy, some digging, on my part.

Sometimes she would drop clues. She would say, “I came back three times to New York.” And I thought, I only knew of two. I found from Ancestry.com that she had, in fact, come back in 1922 with a girlfriend to just come back, and they didn’t go further than New York City. [Her friend] was trying to line up a patron for Berenice, someone who would support a woman artist. Unfortunately, it never happened.

By not getting that support in 1922, 1923, Berenice went to Berlin expecting the money to come. No money came. She was starving and didn’t know what to do. She fled Berlin, gave up her career of trying to be a sculptor, and that’s what landed her in Man Ray’s studio.

She does have quite a lot of setbacks in her life, and it’s not until later she’s recognized for her work. When do people start acknowledging her work as important?

Julia: This is complicated, too. Before the 1970s she had recognition as the photo art world has taken off. She had success as a Paris portrait artist, and then for the 1930s New York City View collection. Both works were celebrated in their day, and her as a photographic artist.

But then she would fall out of fashion. After the portraiture work, the Depression coincided and she couldn’t get more work, which she expected to support her life as a fledgling city photographer. She was hand-to-mouth for five years until the WPA came along. In the 1940s and most of the 1950s, it was touch-and-go freelance work–teaching at the New School was the only steady money she saw at that time.

She had had highs and lows in the art world, and in the 1970s she was one of the older people discovered in that generation of the art galleries that began to sell photographic prints. She printed on demand, and modern prints were what was sold.

Pike and Henry Street in 1936, via Wikipedia

Pike and Henry Street in 1936, via Wikipedia

There’s something so timeless about her work. How did you decide what photographs to include in the biography?

Julia: Well, that was tough. Even for organizing an exhibition, it’s really hard to leave things out. I decided, since it’s not an art book, I would use photographs with a story that related to her life, or there was something interesting she had said about them. That was a way of helping me cut down the things I’d want to show in an exhibition.

What’s a story of Berenice that has stuck with you?

Julia: The one that gets reproduced all the time is when she says, “Buddy, I’m not a nice girl–I’m a photographer.” But the other aspect, to me, is the narrative of this brazen little girl, who was actually not so brazen. She was timid, she didn’t have family to support her, she was really on her own.

In the 1930s, she linked up with the art critic Elizabeth McCausland. They were virtual age-mates and were together for 30 years. But Elizabeth had a little trust fund and solid family back in Kansas. Berenice had no family, no one who understood what she was doing and could be sympathetic.

What’s your experience in wrapping up the book?

Julia: I am thrilled! I am still having fun with it, it’s a delight to share. I want more people to know about Berenice, to treasure her work and enjoy it.

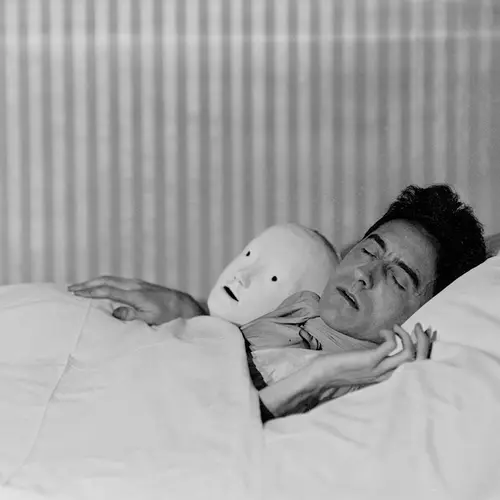

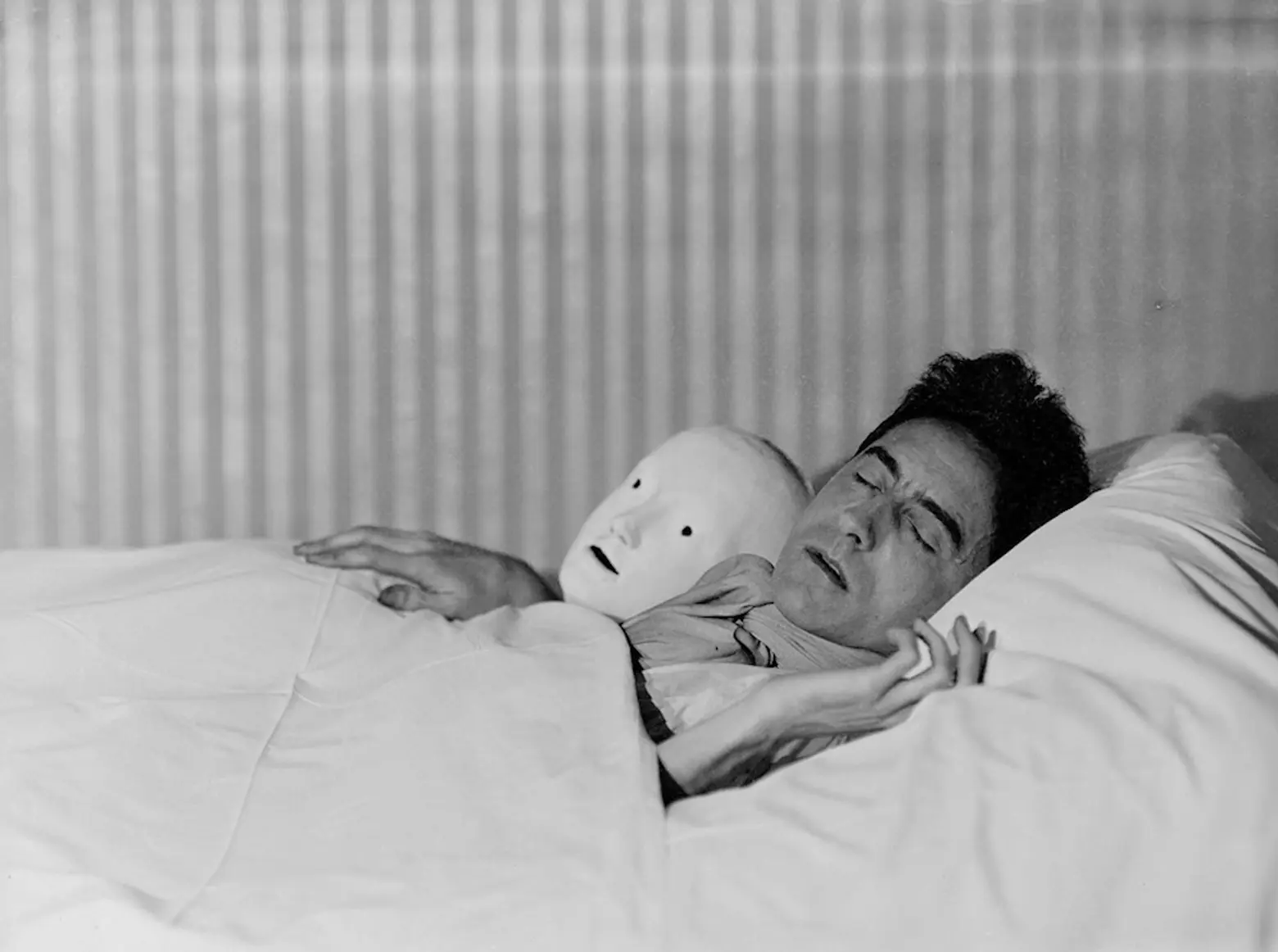

Portrait of Jean Cocteau, from the series “Paris Portraits: 1925-1930,” via Art News

Portrait of Jean Cocteau, from the series “Paris Portraits: 1925-1930,” via Art News

So what’s next for you?

Julia: I am actually going to take a break, but it would be a great pleasure to do more on Abbott in terms of specialized exhibitions. Nobody has done a good exhibition about her portraiture in the 1920s. But, the last portrait she took was in 1961, of Norbert Wiener, the cybernetics pioneer. She kept accepting commissions all her career. It’s an interesting arc because it’s decades long. And as a portraitist, she crossed paths will all kinds of interesting and important people.

“Berenice Abbott: A Life in Photography” is now available at local booksellers and on Amazon.

RELATED: