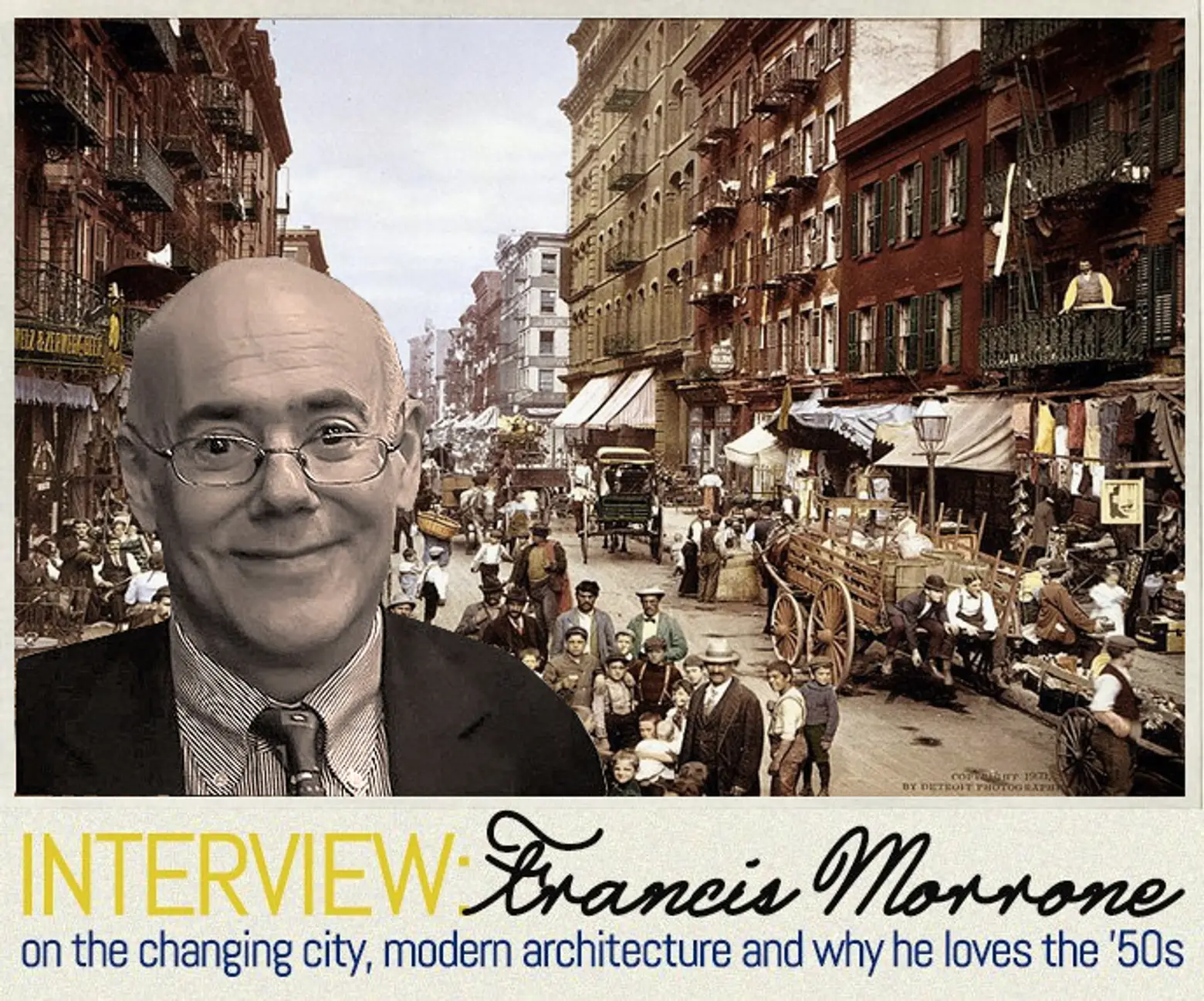

INTERVIEW: Historian Francis Morrone on the Changing City, Modern Architecture and Why He Loves the ’50s

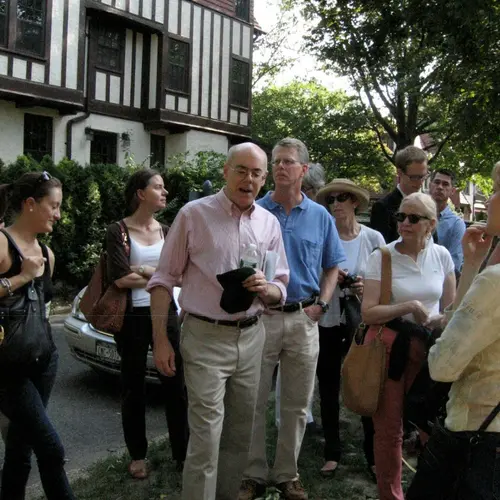

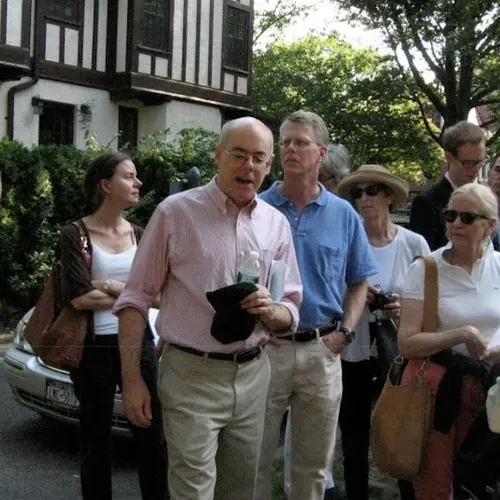

For the man who knows seemingly everything about New York City history, look no further than Francis Morrone. Francis is an architectural historian best known for his writings and walking tours of New York. Of his 11 books, he wrote the actual guidebook to New York City architecture—aptly titled “The Architectural Guidebook to New York City“—as well as the “Guide to New York City Urban Landscapes,” “An Architectural Guidebook to Brooklyn,” and “10 Architectural Walks In Manhattan.” For six and a half years, Francis served as an art and architecture critic for the New York Sun, and he now teaches architectural and urban history at the New York University School of Professional Studies.

As for walking tours, Francis was named by Travel + Leisure magazine as one of the 13 best tour guides in the world. You can catch his various tours, which sell out quickly and cover everything from “Midtown Manhattan’s Side Streets” to the “Architecture and Changing Lifestyles in Greenwich Village,” through the Municipal Art Society. We caught up with Francis recently after he published a much buzzed-about article for the Daily News entitled, “No, New York City Is Not Losing Its Soul,” to talk about his life and work in the city, his opinions on modern architecture and development, and his favorite time period of New York City history.

Park Slope, image courtesy of Matthew Ruttledge

Park Slope, image courtesy of Matthew Ruttledge

What neighborhood do you live in, and how did you end up there?

Francis: I have lived in Park Slope for all of the 35 years I’ve lived in New York. When I moved to New York, the Manhattan neighborhoods that I had once dreamed of living in, like the Village, were already too expensive for people like me, who moved to the city without a lot of money and no prospects of high-paying work.

I had never heard of Park Slope. But a lot of young people like me—aspiring writers, editorial assistants, bookstore clerks, adjunct professors—had begun to move to brownstone Brooklyn, most of which in 1980 had already gone through what I call first-wave gentrification—schoolteachers, psychotherapists, professors and public-interest lawyers as opposed to movie stars, hedge-fund managers or Google executives—and where there was a rich stock of good, cheap apartments, especially the floor-throughs in brownstones that the less-than-rich homeowners desperately needed to rent out to make their mortgages. My more adventuresome artistic peers had already begun moving to Williamsburg.

You are known for your work in New York architectural history. Can you tell us a little bit about how you started on that path?

Francis: I am an architectural historian, but in the fields of New York architecture and New York history I am completely self-taught. In other words, I have never studied New York in a formal academic setting. I never set out to make New York my principal subject. It kind of snuck up on me.

You also give great walking tours around the city. What have been some of your favorite tours?

Francis: I don’t lead walking tours for a living, as some people do, and have the freedom to pick and choose the tours I do. I’m lucky enough to have developed enough of a following over 25 years that a certain number of people will attend my tours regardless of subject matter, and even if the subject is pretty obscure. I like to do tours that help me with the research for books or articles I am writing or courses I am teaching, or that just satisfy my curiosity about something. Thus, whatever it is, I’m doing it because it really, truly interests me, and that’s what I find satisfying. This is just a long way of saying that every tour I lead is my favorite tour.

Francis leading a tour of Forest Hills, Queens

Francis leading a tour of Forest Hills, Queens

Let’s talk about this opinion piece you recently wrote for the Daily News. What inspired you to write it?

Francis: I’m sympathetic to the “vanishing New York” crowd, I really am, but I’d come to feel that too many of them just did not know much about the history of New York, and so didn’t know that we have more mom and pop retail businesses in New York today than at several other times in the city’s history. I’m not saying—nor did I even hint in the piece—that it’s not concerning to see how, in certain locations, retail has been really unbalanced by runaway gentrification. But if we’re going to try to assess how we feel about that, and whether something needs to be done about it, then I think we should at least know something about the history of high-street retail in New York, and the challenges shopkeepers and small business owners have faced in the past.

By the way, when I moved to New York 35 years ago, everyone talked about how bank branches were proliferating and pushing out stores, and how this was going to be viewed as a great negative legacy of the developer-friendly Koch administration. The great symbolic victims back then—they took on an almost mythic status—were shoe repair shops and locksmiths.

The kids who glamorize the 1970s ought to be aware that runaway blight—of the sort Brooklyn experienced in the 1960s and 1970s—does an even more thorough job of unbalancing retail than does runaway gentrification. And might I point out that I never, not once, say in the piece that New York is not losing its soul. I never in my writing refer to the “souls” of cities. That’s the headline, and the only part of the piece, I’m convinced, that many of those who called me obscene names read. Writers don’t write their own headlines. You’d think more readers would know that!

“SKIPPED, 1977” photo by Susan Lorkid Katz, courtesy the Museum of the City of New York

“SKIPPED, 1977” photo by Susan Lorkid Katz, courtesy the Museum of the City of New York

You make a good point in the article that New York is a city of constant change. Do you think that the change we’re seeing now threatens to make the city just too expensive for newcomers looking for cheap housing?

Francis: Oh yes. And it saddens me no end to know that the me of 35 years ago probably would not move to New York today. But much more do I feel for the immigrants subjected to human warehousing in Queens basements. At the same time, I try to remain philosophical. I know an awful lot of people who have left New York and I myself plan to live my “golden years” someplace else. A lot of the problems New York faces are not unique to New York. The cratering of the creative middle class that Scott Timberg writes about so well in “Culture Crash” is happening everywhere, and remarkably few of the examples in his book are drawn from New York. But at least other places are cheaper.

Sunset Park courtesy of Chung Chu

Sunset Park courtesy of Chung Chu

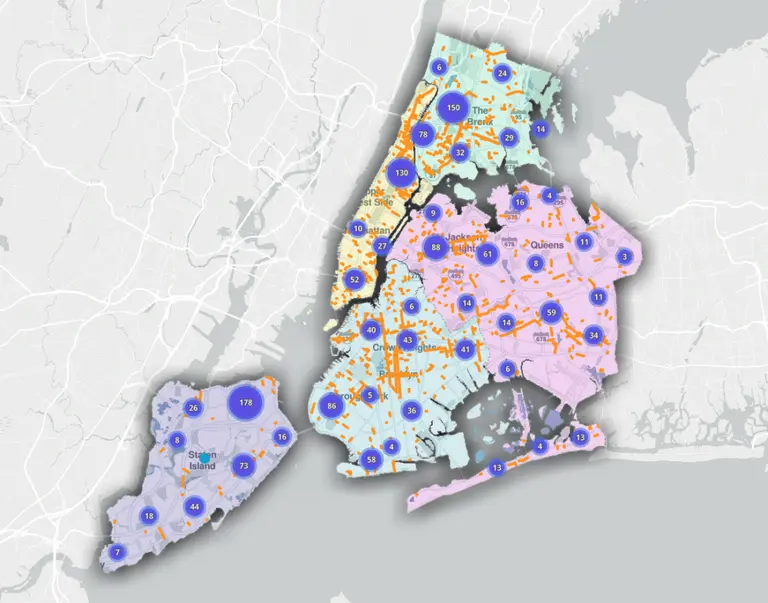

You mention Sunset Park as a neighborhood that’s particularly diverse and vibrant. What other NYC neighborhoods attract you in that regard?

Francis: Jackson Heights is diverse in much the same ways. What makes Sunset Park so compelling, though, is to know how desolate its main streets were 35 years ago.

What’s a period of NYC history you wish you could have experienced yourself?

Francis: 1950s.

Why?

Francis: I like transitional periods. The ’50s was the ultimate transitional period. The old industrial and port city was still there, but fast yielding. The city was entering into the painful transition to a post-industrial metropolis, and there was wreckage all around. It was the urban renewal era, and an era of intensive private building as well, and the city just vibrated with jackhammers.

1950s New York photo by the U.S. Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation, courtesy Wikimedia Commons

1950s New York photo by the U.S. Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation, courtesy Wikimedia Commons

We think there’s a lot of building going on in the city today, but by historical measures it’s actually rather meager. In the very years Willem de Kooning was painting his most significant paintings, in his 10th Street home and studio, three gigantic apartment buildings were built within half a block of him. When you look at his “Woman” paintings, you might want to note that they were made amid the deafening sounds of demolition and construction. I hate being around demolition and construction—who likes it?—but what moves me about the fifties is the sort of dawn of a new consciousness of the city. Henry Hope Reed’s walking tours (begun 1956), Joseph Mitchell’s “Old Mr. Flood” and “The Bottom of the Harbor,” Joseph Cornell’s boxes and Frank O’Hara’s “I did this, I did that” poems, Jane Jacobs’s “Downtown Is for People” (1958), and so on. What an exciting time it must have been to be in New York.

Willem de Kooning on 10th Street photo, courtesy Fred W. McDarrah via WYNC

What about a time period you are thankful you didn’t have to live in?

Francis: I don’t know if I can answer that!

What are your opinions on the current landscape of architecture going up in New York? What excites or underwhelms you?

Francis: Less said the better? Actually, I’m very pleased by the way the World Trade Center is shaping up. I like the 9/11 Memorial and Museum, I like 4 WTC. Not so much 1 WTC. I am looking forward to the PATH station, and I predict a backlash to the backlash. And think Brookfield Place has turned out really well.

World Trade Center photo, courtesy World Trade Center Progress

World Trade Center photo, courtesy World Trade Center Progress

God help me, not only do I like 4 WTC, I also like the same architect’s (Maki’s) 51 Astor Place. The precision and sleekness of those buildings make almost every other glass-curtain-wall building in the city look like something that fell off the shelf in the hardware store. Going back a few years, it almost unnerves me to realize how fond I’ve become of the Time Warner Center, which I said I hated when it was built. So, contrary to what some people think, I don’t hate modern architecture. I hate architecture that postures, and disproportionately a lot of that is modern. A too-easy example would be 41 Cooper Square. It’s failed to grow on me.

Favorite New York architect—past or present—and your favorite building by them?

Francis: I like Bertram Goodhue (Church of the Intercession, St. Vincent Ferrer, St. Thomas Church). He and his sometime partner Ralph Adams Cram may be my favorite American architects.

Church of the Intercession photo, courtesy Wikipedia

Church of the Intercession photo, courtesy Wikipedia

Your favorite New York institutions?

Francis: If there is one thing that keeps me in New York it is the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which opened in Central Park in 1880. I’m devoted to a very old-fashioned Italian restaurant on Court Street called Queen, which has been in business for more than 50 years. I still buy all my clothes at Brooks Brothers (founded 1818), but their quality is not what it once was.

What are you working on now?

Francis: I find that as soon as I talk about what I’m working on I lose the will to work on it.

+++

For more from Francis, check out his books:

- The Architectural Guidebook to New York City

- Guide to New York City Urban Landscapes

- An Architectural Guidebook to Brooklyn

- 10 Architectural Walks Through Manhattan

RELATED STORIES: