INTERVIEW: Meet Mary French, the woman archiving New York City’s 140 cemeteries

Photos courtesy of Mary French

In a city as tight as New York, it’s no surprise we’ve long struggled to figure out what to do with our dead, from acres-wide cemeteries to those wedged into forgotten slivers of city blocks. The city now boasts 140 cemetery sites, and Mary French has visited them all. Mary is the author of the New York City Cemetery Project, a chronicler of “the graveyards of this great city.” Though cemeteries may come with dark connotations, Mary sees them as prime opportunities to understand the history of New York. As she explains on her website, “For those with a passion for culture and history and a curiosity about the unknown, cemeteries are tantalizing spots that provide a wellspring of information about individual lives, communities, religions, and historic events.”

On NYC Cemetery Project you can read the histories of existing and long-gone cemeteries and the interesting New Yorkers living six feet under, alongside a trove of historic photos and maps. It’s a labor of love (and intense research) for Mary, who has a background in anthropology and library science. With 6sqft, Mary explains what first attracted her to the cemeteries of New York and what it’s like delving into their past. She also explains why she thinks many might be lost to the pressures of development in New York.

A hillside Chinese section at Cypress Hills Cemetery, photo by Mary French

A hillside Chinese section at Cypress Hills Cemetery, photo by Mary French

Let’s talk about your background — I know you’ve worked at museums.

Mary: I have masters degrees in anthropology and library science. My first jobs were in cultural resources management, management of archeological sites and historic properties. Then I worked in museum curation and research. I’ve done the library and archive thing, too.

I came to New York for a position with the Museum of Natural History, where I worked for a couple of years in the anthropology departments.

So what sparked your curiosity in New York cemeteries?

Mary: I have some experience managing archaeological resources and historic properties, but I also understand the museum side of things. Everything you look at, you kind of want to catalog it. When I moved to New York, I started to see remnant cemeteries and wondered, how did these survive? I also spent a lot of time in Queens, seeing many of the cemeteries there still in operation.

All cemeteries have their own character, their own personality, and community to them. People always know about Green-Wood or Woodlawn and are mostly interested in where the famous people are buried. I was interested more in what cemeteries teach us about social history, land use, how land use has changed over time, and the ones that disappeared. I couldn’t find anyone writing about that.

It started out as my own personal interest, and I thought I’d write a book about this. But I started putting stuff on the web as things captured my interest. The blog is meant to be an encyclopedia of cemeteries, and eventually, hopefully, someday, I’ll write a book that captures the whole picture of what New York cemeteries are about.

Mount Zion Cemetery, photo by Mary French

Mount Zion Cemetery, photo by Mary French

For New Yorkers who don’t think much about cemeteries, what would you tell them about the wealth of information that you can find inside?

Mary: There are lots of times I look at a cemetery, tucked into a neighborhood, and people who lived there their whole life never knew a cemetery was there. It would be nice to have historical markers to tell people [the significance].

The first cemetery that sparked my interest is Mount Zion, a Jewish cemetery in Queens. A lot of people buried there — Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe in the late 1800s, early 1900s — had been living in the tenements in the Lower East Side and Brooklyn. The cemetery is so crowded, burial conditions that are very reflective of the life these people had. Groups from the same village would buy plots together, or unions or different social groups they belonged to. They’re buried next to these people in the same crowded conditions they lived in.

The Jewish and Catholic cemeteries of New York hold some of the most important Jewish and Catholic people in the country. It’s reflective that this is where a many of the immigrants were coming first.

What does your research process look like?

Mary: I try to go and see what the cemetery reveals to me, and then I do the research afterward. From the research side, I go through old maps to see how the land has changed. I go through old newspaper articles, I’ve also gone to some archives. I do a lot of photographic research as well, like the New York Public Library’s photo archives.

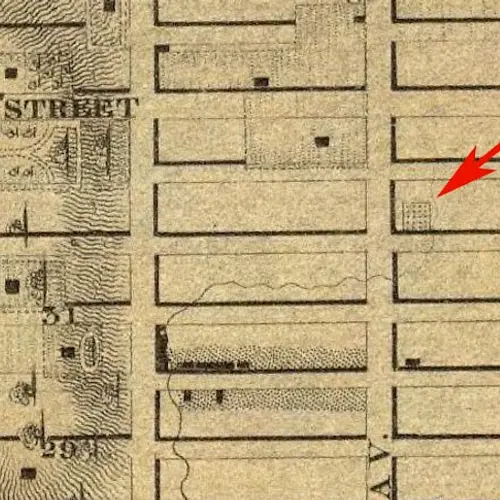

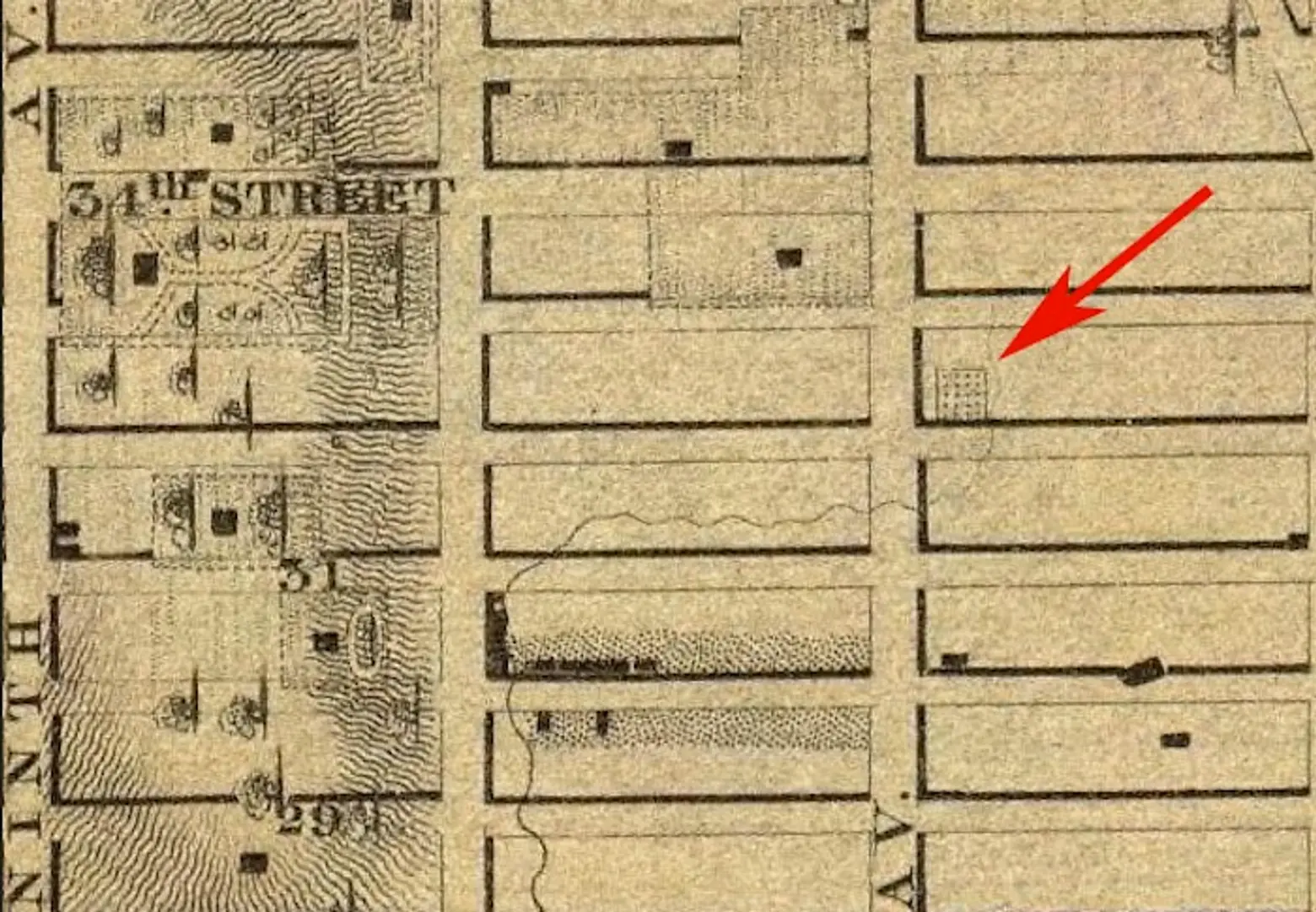

An 1836 map showing B’nai Jeshurun’s cemetery on the current Hotel Pennsylvania site, via NYC Cemetery Project

An 1836 map showing B’nai Jeshurun’s cemetery on the current Hotel Pennsylvania site, via NYC Cemetery Project

What are some interesting stories on how New York has lost some of its cemeteries?

Mary: There was one under the Hotel Pennsylvania, one of the early Jewish cemeteries. To imagine, the first Ashkenazi Jewish cemetery in New York City, under the hotel.

Most were removed in the mid to late-1800s, and there were no laws protecting cemeteries and historic properties back then. There were no controls for it. What’s shocking to me is that even churches could be reckless with remains — you read about them piling [bodies] into carts and dumping them in the river. Unless it’s their own family members, I don’t think people feel a sense of duty to the bodies, especially dealing with the pressures of economics or trying to sell the property.

Are there particular discoveries inside cemeteries that have stuck with you?

Mary: Well, we think we have this idea that Europeans are more respectful to European remains, as opposed to other ethnic groups, and it’s just not true. There’s a lack of respect in general, for the dead, under those pressures I mentioned before.

New York is a city that’s always rebuilding, and then we have to think about how preservation fits into that story as well. What’s your opinion on the preservation of cemeteries in a city like this?

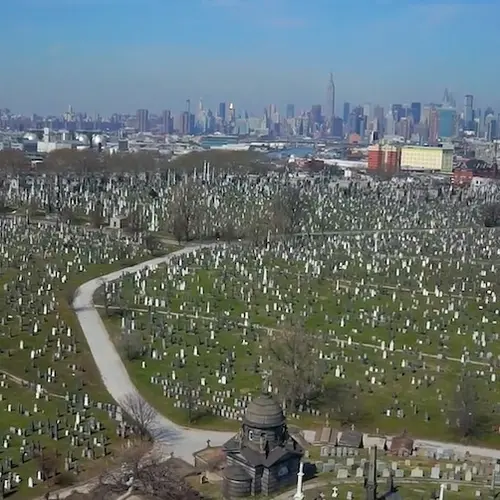

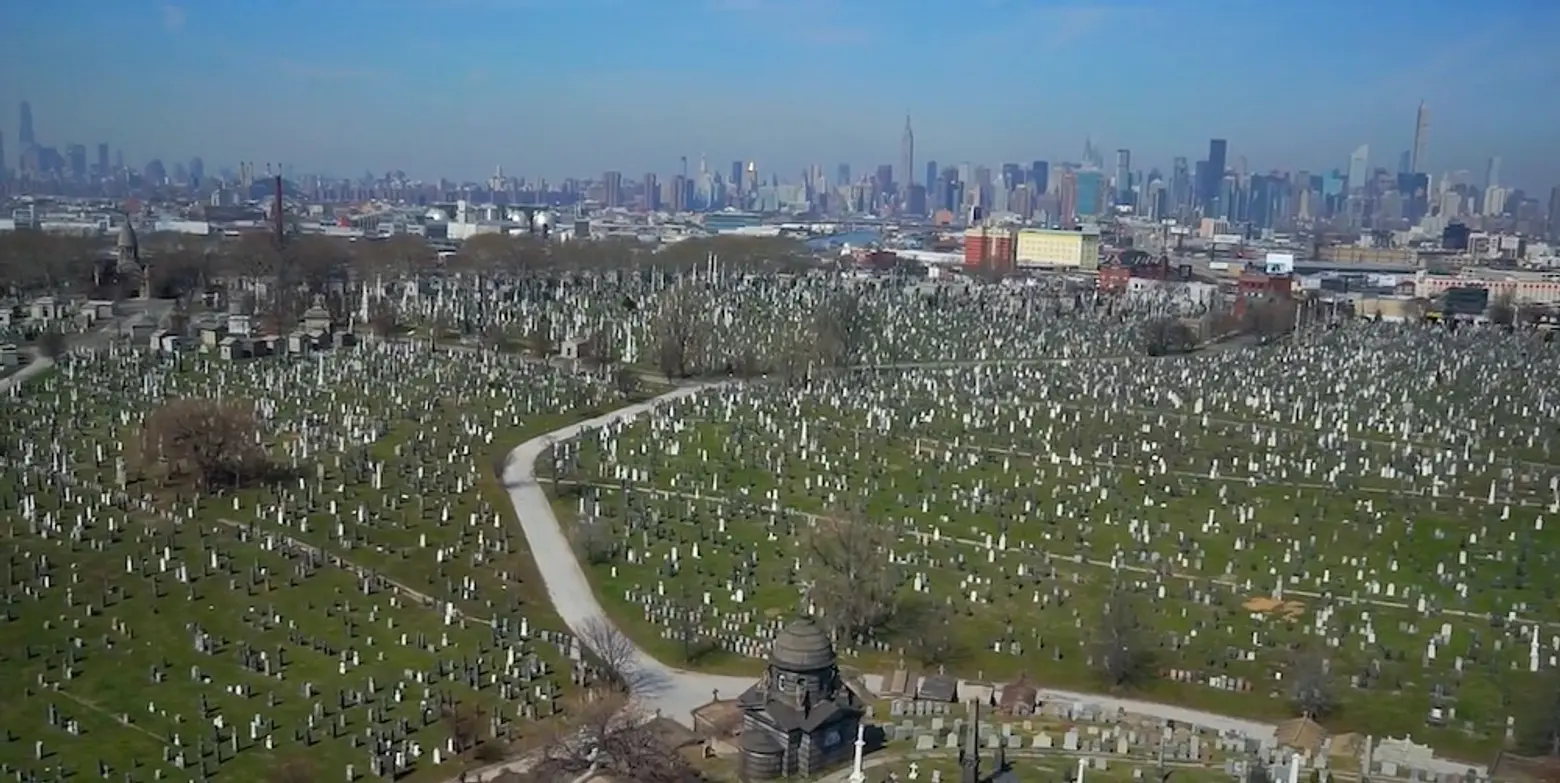

Mary: I obviously think it’s very important, or I wouldn’t be doing this. But I’ve given a lot of thought to whether some of the big cemeteries in Queens will be built over one day. Honestly, I think probably so. History shows the needs of the living outweigh the needs of the dead. It’s not uncommon for cities to remove their cemeteries from the cities, actually. The idea of a final resting place being final is not borne out by history. Still, I think it would be a huge loss.

Photo of Queens’ Calvary Cemetery by James Sengul, via NYC Cemetery Project

Photo of Queens’ Calvary Cemetery by James Sengul, via NYC Cemetery Project

What’s your latest work with the site?

Mary: The newest thing I’ve been doing are stories about really unique individuals, writing about individuals and not just the cemeteries. I’m calling it “Lives Unearthed.”

How do you pick those individuals?

Mary: The first one I did was a person who was so astounding, with a unique story I didn’t see covered anywhere else. It also linked very strongly to the cemetery she’s buried in.

Another one is an artist who committed suicide in City Island in a very public fashion. These are stories that were in the paper the time they happened, but they’ve been forgotten. I think they’re just touching stories that deserve to be mentioned today.

What are the areas you’ve been spending a lot of time in around New York?

Mary: Last summer, I finished all the cemeteries on Staten Island. That was interesting because I got to see all of Staten Island by foot. Lately, it’s been revisiting some of the cemeteries in Queens.

So is the book actively in the works?

Mary: It’s always on my mind, but I’ve been focused more on gathering and putting stuff on the website right now. I don’t think people realize the hours of research that goes into one of those blog entries. I come from a scholarship background, where you have to verify your information and document your sources. I know the Landmarks Preservation Commission reads the blog, and I keep in mind the different kinds of people who use the information. I feel a sense of responsibility that goes beyond writing a clever blog entry.

RELATED: