INTERVIEW: The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project talks gay history and advocacy in NYC

“Where did lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) history happen in New York City? In what buildings did influential LGBT activists and artists live and work, and on what streets did groups demonstrate for their equal rights?” These are the questions that the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project is answering through a first-of-its-kind initiative to document historic and cultural sites associated with the LGBT community in the five boroughs. Through a map-based online archive, based on 25 years of research of advocacy, the group hopes to make “invisible history visible” by exploring sites related to everything from theater and art to social activism and health.

To mark Pride Month, 6sqft recently talked with the Historic Sites Project’s directors–architectural historian and preservation professor at Columbia Andrew S. Dolkart; historic preservation consultant Ken Lustbader; and former senior historian at the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission Jay Shockley–along with their project manager, preservationist Amanda Davis, about the roots of the initiative, LGBT history in NYC, and the future of gay advocacy.

L to R: Co-directors Ken Lustbader and Jay Shockley; project manager Amanda Davis; co-director Andrew Dolkart; MCNY curator Donald Albrecht

L to R: Co-directors Ken Lustbader and Jay Shockley; project manager Amanda Davis; co-director Andrew Dolkart; MCNY curator Donald Albrecht

Give us some background on the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project. Where did the idea come from?

Jay: Andrew Dolkart, Ken Lustbader, and I, all historic preservationists, had always wanted to do something new about LGBT place-based history in NYC. I was set to retire from my position as senior historian at the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission, where for the past 25 years I had been including LGBT history in city designation reports. At the same time, Ken, Andrew, and I found out about the Underrepresented Communities grant from the National Park Service in 2014 and submitted a proposal.

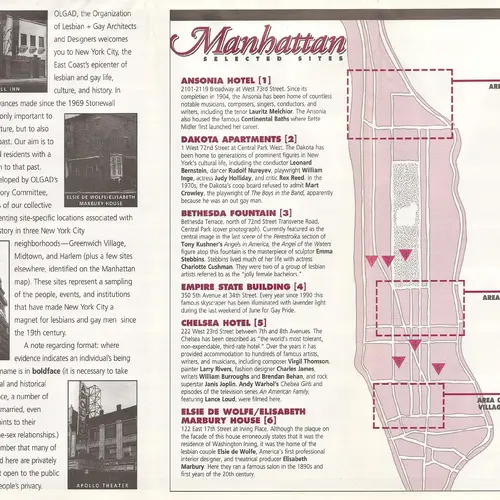

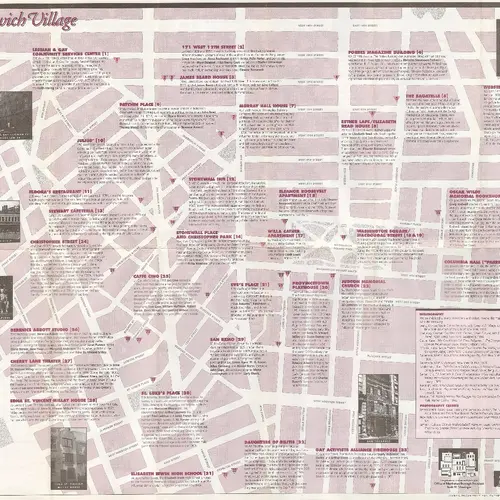

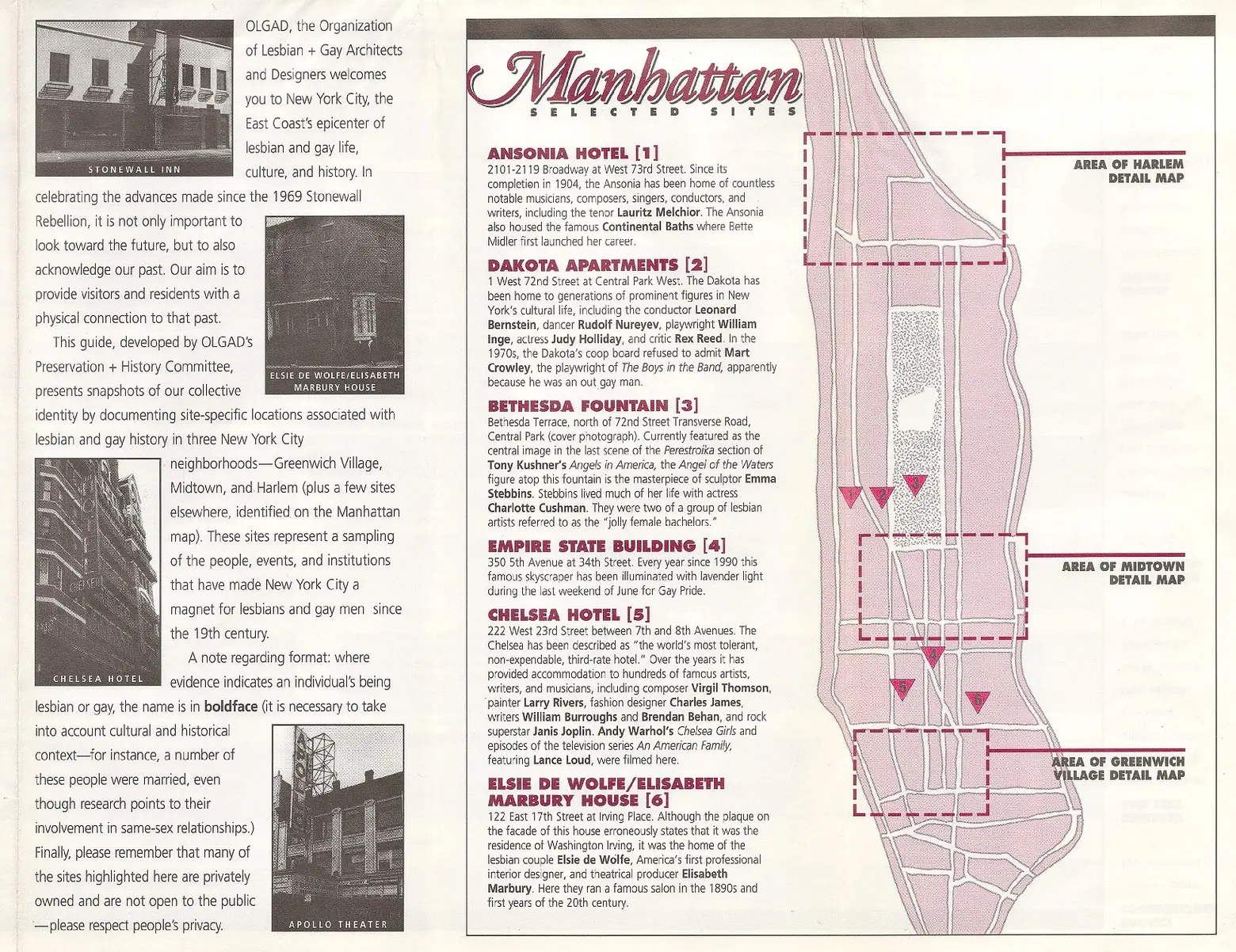

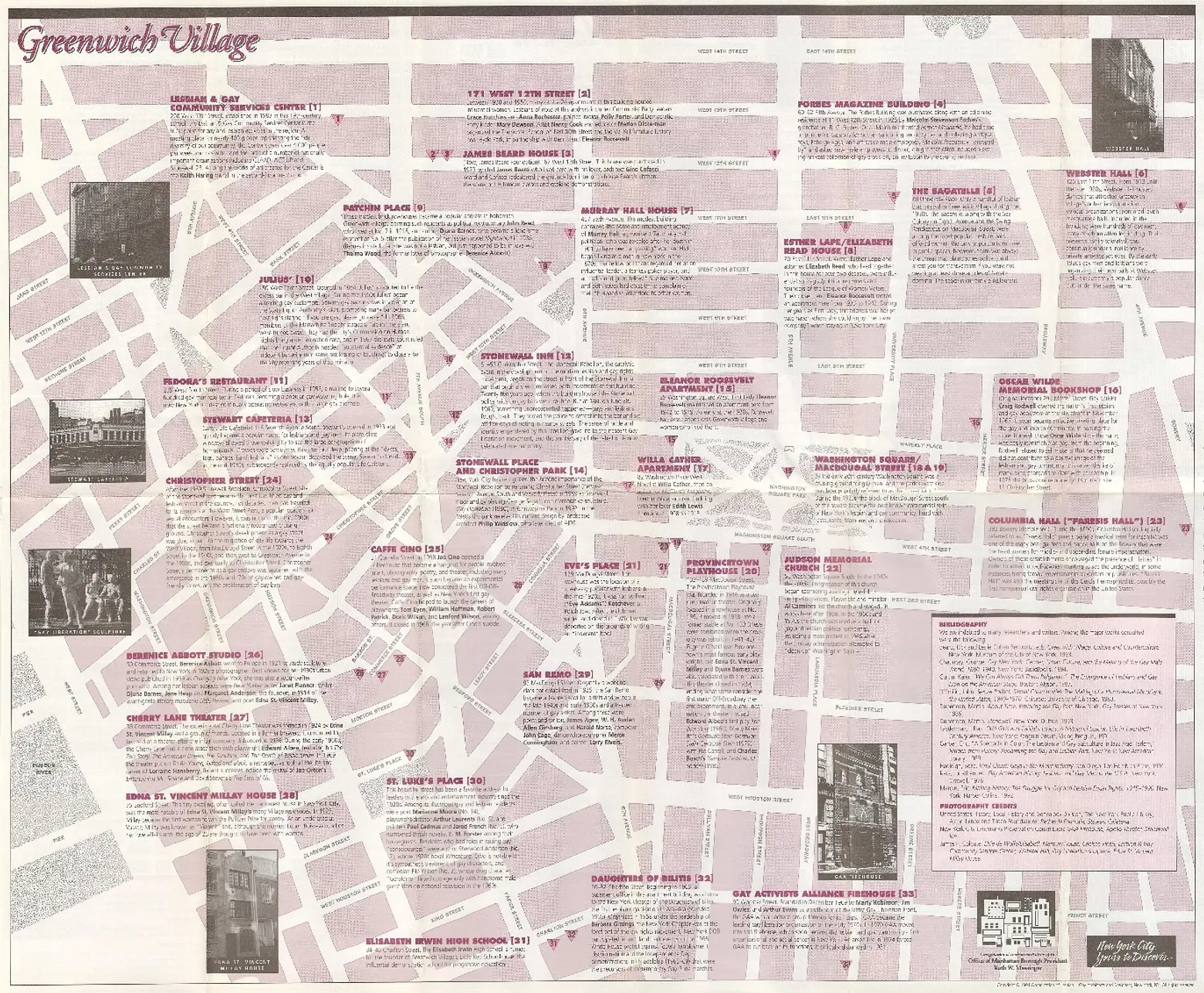

The idea for creating an interactive map came from a fold-out map the three of us helped create back in 1994 as part of the Organization of Lesbian and Gay Architects + Designers (OLGAD). That map was created to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Stonewall, and we believe it’s the first map in the country to specifically call out LGBT historic sites at a time when people shrugged off the idea of recognizing and preserving sites of LGBT significance.

View a PDF of the entire 1994 OLGAD map here >>

View a PDF of the entire 1994 OLGAD map here >>

Ken: As Jay said, our idea to document LGBT place-based history started 25 years ago. In 1991, I was in graduate school for historic preservation and wanted to demonstrate that LGBT historic sites had equal significance to other culturally important places. I wrote my thesis on this topic using Greenwich Village as a case study. At the same time, I connected with Andrew and Jay on the OLGAD map. We all continued working in the preservation field and in early 2014 we felt an urgency to embark on a comprehensive project to document LGBT historic sites in NYC. The urgency dovetailed with the National Park Service grant announcement. The subsequent grant is administered through the New York State Historic Preservation Office and we’re working with them on new LGBT nominations to the National Register of Historic Places and the overall project.

Screenshots of the current NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project map

Screenshots of the current NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project map

How does researching and documenting LGBTQ sites compare to other preservation projects?

Jay: Our project is primarily a cultural heritage survey, so for the bulk of the sites we’re not using architectural significance as the sole determining factor. We care more about the specific history that occurred at the location. Identifying and researching LGBT sites is challenging since the history is hidden, historic terminology and language differs from today, and there’s a burden of LGBT proof that often isn’t required for other types of cultural survey projects. In many cases, the sites we’re including are vernacular and have been altered, but the history is important.

Amanda: The first thing I found out is how important it is to get people on board with the idea that LGBTQ sites even exist to begin with. Most people think this history doesn’t go back very far and tend to focus on bars and activism beginning with the 1969 uprising at Stonewall. Also, as preservationists, we rely on historic documentation to piece together the history of a building, but that can be hard to find when a gay person or his/her family didn’t save their letters, photos, etc. that would reveal the person’s homosexuality (this goes back to the burden of proof that Jay mentioned). And as for the buildings themselves, they may have significant social and cultural histories, but they may be modest-looking structures or altered to the point they have lost their architectural integrity. This can make it difficult to convince people that it’s worthy of being a protected landmark.

The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project celebrates the amended designation of the Alice Austen House Museum to include its significance as a National Register site of LGBTQ history, the first lesbian site in NYC. Co-director Ken Lustabder (far left) and project manager Amanda Davis (third from right)

The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project celebrates the amended designation of the Alice Austen House Museum to include its significance as a National Register site of LGBTQ history, the first lesbian site in NYC. Co-director Ken Lustabder (far left) and project manager Amanda Davis (third from right)

Is there one site or fact related to this history that’s surprised you most as you’ve done your research?

Jay: A surprise to me was that we were able to include several churches that have had an incredible relationship with the founding of the earliest gay rights groups, such as Judson Memorial Church, the Church of the Holy Apostles, (the former) Washington Square United Methodist Church, and so on. We were pleased to include these institutions to counterbalance the other religious spaces that have been sites of oppression against the LGBT community.

Amanda: It’s hard to choose just one, but in light of our recent amendment to the Alice Austen House to include its LGBT history, I would have to say that I was genuinely surprised to find out just how much of a role Austen’s partner Gertrude Tate played in helping them hold onto the house after Austen lost everything in the 1929 stock market crash. Tate used income from teaching dance lessons to support the couple and ultimately convinced Austen to open a tea room on the property (the Alice Austen House Museum provided us with an incredible card advertising this tea room, which you can see on our website). This site has really inspired me to think more closely about how we interpret the residences of influential LGBT people, which is particularly relevant for house museums where too often a partner of the same sex is erased from history. I hope the Alice Austen House Museum story is just the beginning.

Stonewall today

Stonewall today

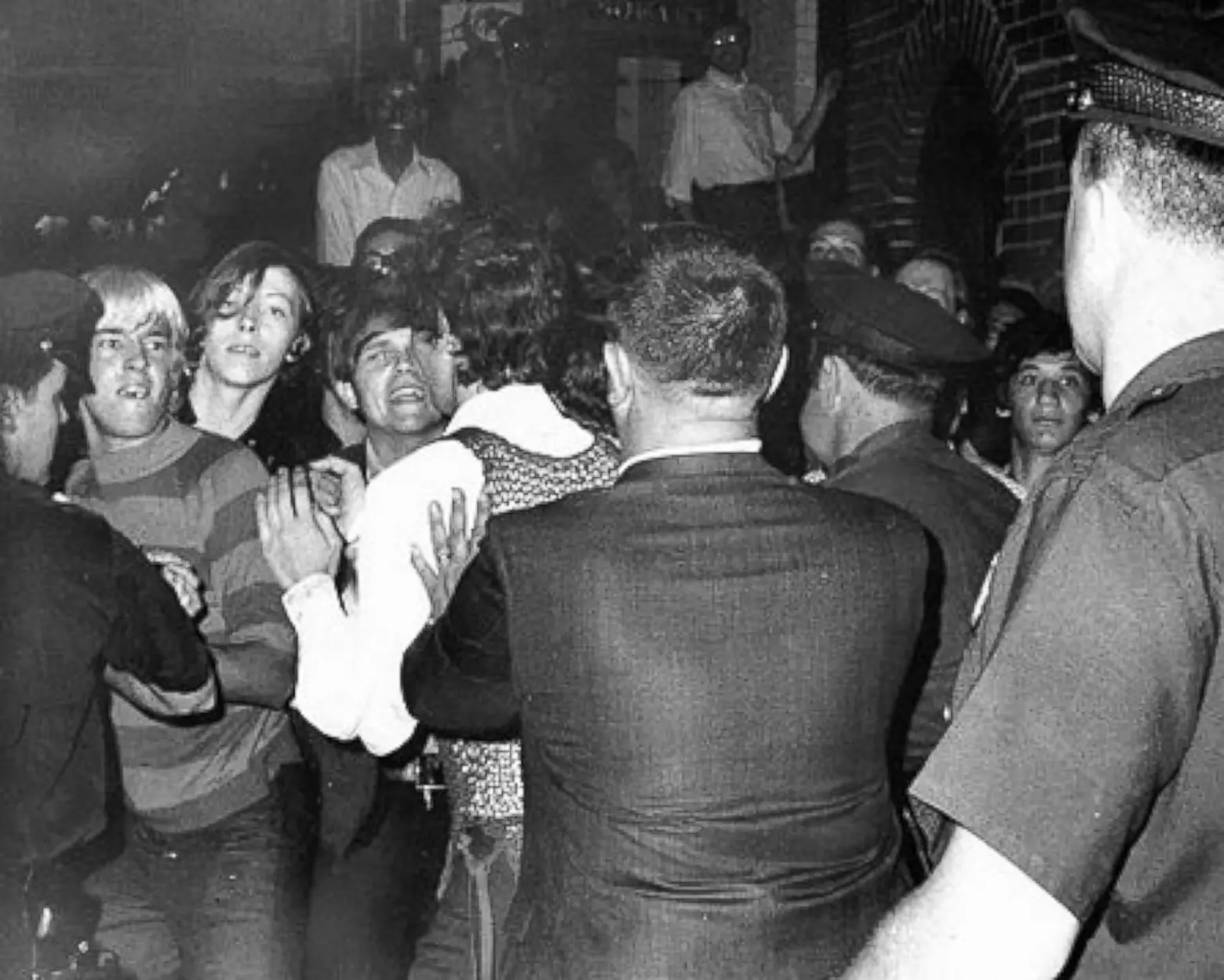

Historic photo of the Stonewall Riots

Historic photo of the Stonewall Riots

The Village is probably the neighborhood most closely associated with LGBT history in NYC, specifically the Stonewall Inn. What are your thoughts on Stonewall being the most prominent symbol of gay history?

Jay: Obviously Stonewall is the most known in NYC, nationally, and worldwide, but our project is working to show that LGBT history pre-dates 1969, and that history is essential to put Stonewall in context. For example, as Ken and I are developing a walking tour of sites around Stonewall in partnership with the National Parks Conservation Association, Julius’ and the Snake Pit have an absolutely related history that should be more well known and is connected to the pre- and post-Stonewall political movement.

Amanda: For me, as a preservationist, it’s great to see a building be so loved by so many people across the world. I remember hearing someone say that when he first moved to New York as a young gay man and stood in front of Stonewall he was overcome with emotion. There are still parts of the country and the world where gay and trans people do not feel comfortable being themselves and so to have this physical space that stands for LGBT pride, solidarity, visibility, community, and equality is really important. Stonewall was not the first place where the LGBT community fought for their equal rights (there’s a much larger story there), but I love what it stands for and that is has been recognized at the local, state, and federal levels as a site that is unquestionably worth preserving.

Ken: The Village will always be closely associated with LGBT history because it has been more documented and preserved than many other neighborhoods. But who knows what the future holds when historians uncover LGBT narratives about other areas. We already know that Harlem, Jackson Heights, Park Slope, and the Brooklyn waterfront have rich LGBT stories. Recognition of Stonewall helps people understand what we’re referring to as LGBT place-based history. But there are so many other sites that need to be presented to convey the full diversity of the community in all five boroughs. We’re trying to do that through research and appeals to the public to suggest sites for inclusion in our research.

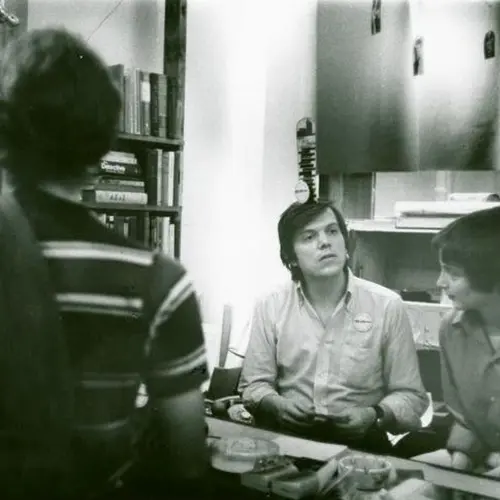

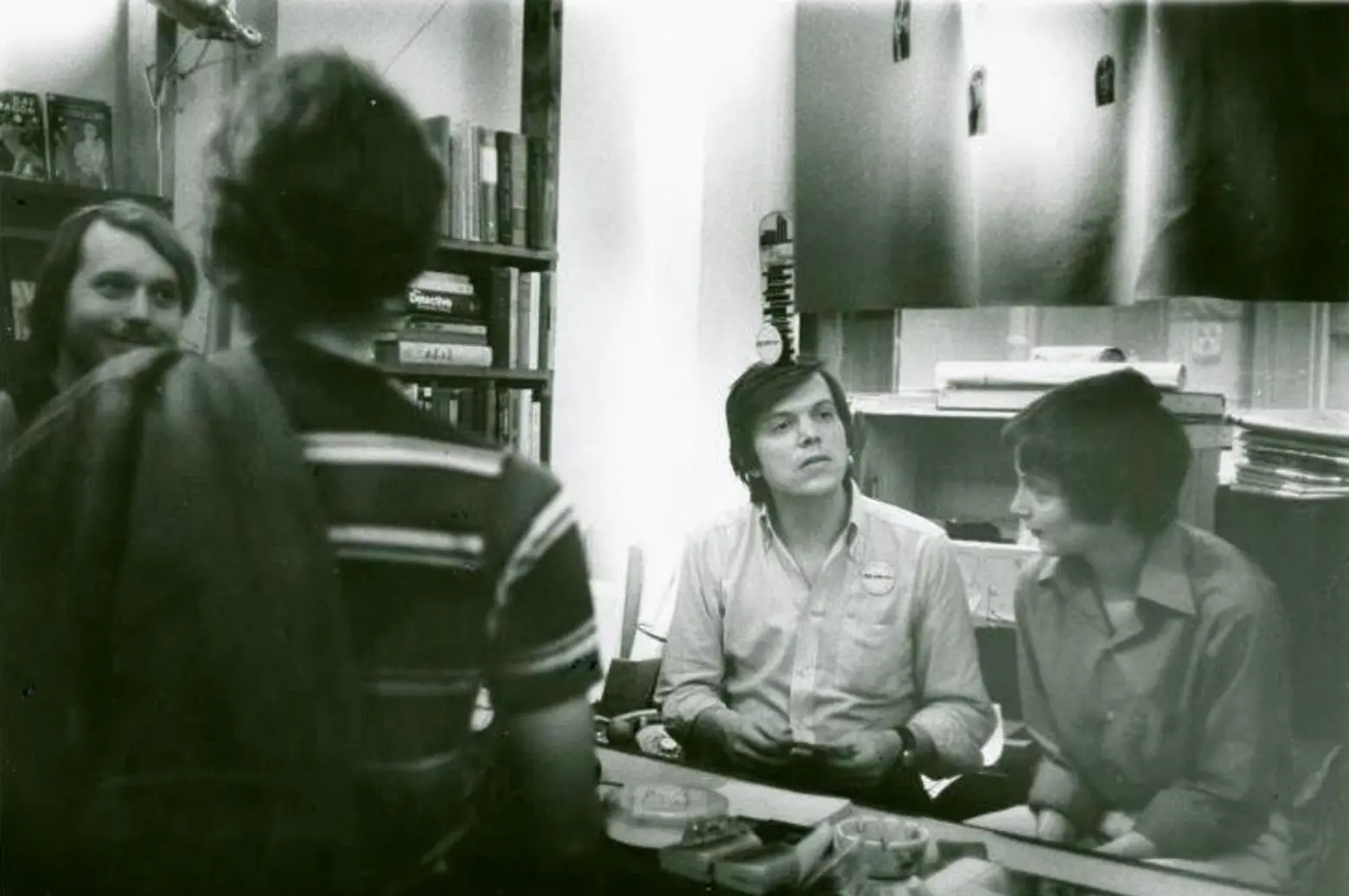

Craig Rodwell with friends at the Oscar Wilde Bookshop at 15 Christopher Street (second location) in an undated photo. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Craig Rodwell with friends at the Oscar Wilde Bookshop at 15 Christopher Street (second location) in an undated photo. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Along those lines, what other sites in the Village do you think are equally important?

Amanda: Just one is the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookstore, which first opened on Mercer Street in 1967 before moving to its long-time location on Christopher Street. The store was established by Craig Rodwell, a significant gay rights activist, two years before Stonewall in order to provide the LGBT community with positive literature by gay and lesbian authors. This was particularly important in that era because gay people were really only portrayed negatively in the media, movies, and books. It must have been a revelation to open a book in that store and read something positive about yourself.

Meeting at the GAA Firehouse, 1971. Photo by Richard C. Wandel. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Meeting at the GAA Firehouse, 1971. Photo by Richard C. Wandel. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Ken: I’d like to venture out of the Village to nearby Soho to highlight the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) Firehouse at 99 Wooster Street. GAA was formed in December 1969 and became one of the most influential gay activist groups in the early 1970s. They used the former firehouse as its headquarters and it became an important LGBT political and cultural community center. They planned many of their political events here and hosted its famous Saturday night dances as well as Vito Russo’s “Firehouse Flick’s.”

How does the changing socio-economic dynamics affect the heritage of the neighborhood? Was that one of the drivers behind doing this project at all?

Jay: The Village is extraordinarily lucky that so many buildings are protected by historic status and included in the Landmarks Preservation Commission designation reports. But virtually none of the properties, other than Stonewall, are documented and interpreted for their LGBT associations. One of the reasons this project is being done is to interpret these sites and alert people about their importance to LGBT and American history. We aren’t affiliated with the Landmarks Commission or any other public agencies, but we do hope our project can serve as a guide in designating more landmarks for their LGBT significance.

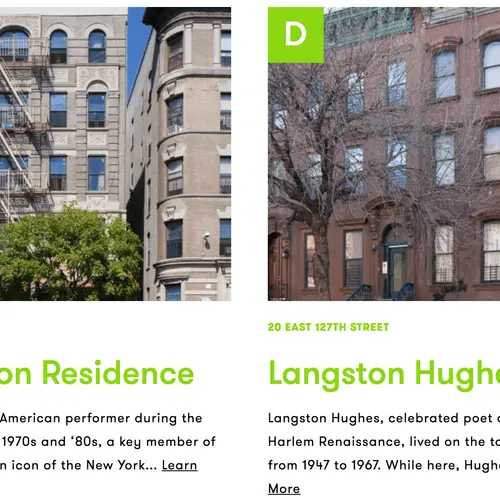

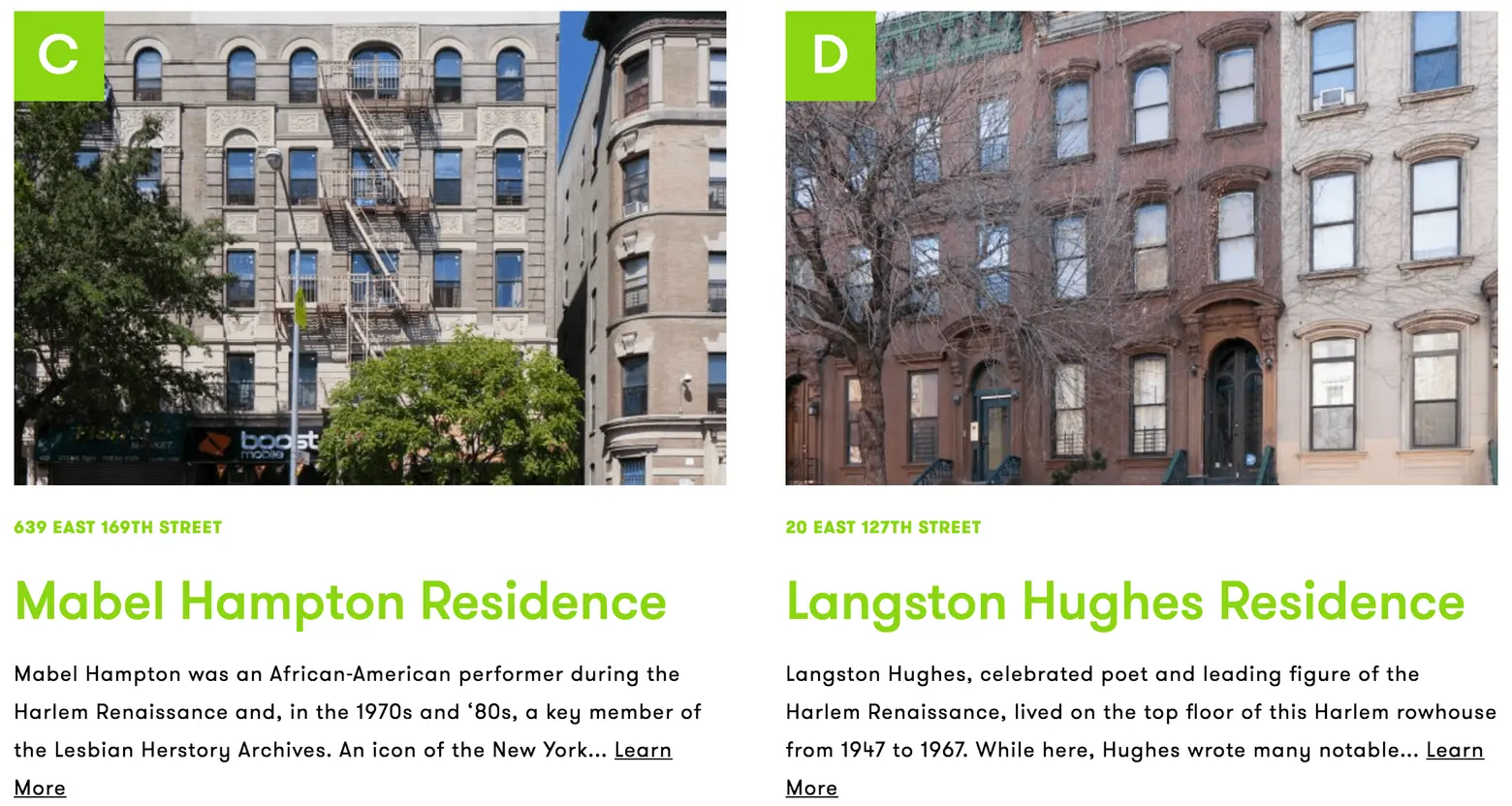

Sites in the Bronx and Harlem featured on the map

Sites in the Bronx and Harlem featured on the map

You mentioned Harlem, Jackson Heights, Park Slope, and the Brooklyn waterfront as other neighborhoods with rich LGBT narratives. Would you say there’s one area that rivals the Village in terms of this history and activism?

Amanda: I would definitely say that Harlem has an incredible LGBT history that dates back to at least the 1920s. We had a great meeting with Harlem SAGE, a group for LGBT elders, some time ago and it was wonderful to listen to members talk about the places that meant so much to them. So many important gay African-American artists, writers, and others came through Harlem, some of whom we have on the map so far.

Also, as a Queens resident, I was thrilled to learn about the importance of Jackson Heights as a center for LGBT history and activism. Because the 7 train connects the neighborhood to the Times Square theater district, Jackson Heights has been home to LGBT people associated with Broadway theater for nearly a century. With activism, we’ve really only scratched the surface on our map with Julio Rivera Corner, but we’re looking forward to adding more sites.

(left to right) Mattachine Society members John Timmons, Dick Leitsch, Craig Rodwell, and Randy Wicker being refused service by the bartender at Julius’, April 21, 1966. Gift of The Estate of Fred W. McDarrah.

(left to right) Mattachine Society members John Timmons, Dick Leitsch, Craig Rodwell, and Randy Wicker being refused service by the bartender at Julius’, April 21, 1966. Gift of The Estate of Fred W. McDarrah.

Julius’ bar today, photo by Christopher D. Brazee/NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project

Julius’ bar today, photo by Christopher D. Brazee/NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project

When you first started out, only two of the roughly 92,000 sites on the National Register of Historic Places were connected to LGBTQ history and there are now 14. Your project is associated with three recent nominations in New York City –the Greenwich Village bar Julius’, the Chelsea home of civil rights leader Bayard Rustin, and just last week, photographer Alice Austen’s Staten Island home. Why did you choose these as the inaugural trio?

Jay: We selected Julius’ and Austen to relate to their specific anniversaries. For example, we knew that we had to nominate Julius’ for the 50th anniversary of the Sip-In in April 2016 and had full support of the bar owner and building owner. Austen’s 150th birthday was in 2016 when we started the nomination and we had the wonderful support of the house museum executive director and board. For Rustin, we were fortunate that a colleague in Washington, D.C. was already working on the nomination and so that was folded into our project portfolio of nominations.

Ken: Our National Park Service grants require a total of seven nominations to the National Register of Historic Places for LGBT properties in New York City. The goal is to increase diversity on the register since the LGBT community is so underrepresented and we want to make sure we nominate sites outside of Manhattan. In putting forth a nomination we must demonstrate that the site retains its architectural integrity from the period of significance. Even though a nomination is honorific (meaning no additional regulations would be put on the building), we also must obtain consent from the building owner, which can be challenging. Nominating a site requires an intense amount of research, documentation, and writing. A nomination is a lengthy document that goes into the state and federal records in perpetuity to ensure that a site’s LGBT narrative is recognized as significant to US history.

Project co-director Ken Lustbader and project manager Amanda Davis at the grave in Woodlawn Cemetery of J.C. Leyendecker (1874-1951), well-known illustrator who created over 300 covers for “The Saturday Evening Post” and rivaled Norman Rockwell in the field of magazine illustrations.

Project co-director Ken Lustbader and project manager Amanda Davis at the grave in Woodlawn Cemetery of J.C. Leyendecker (1874-1951), well-known illustrator who created over 300 covers for “The Saturday Evening Post” and rivaled Norman Rockwell in the field of magazine illustrations.

What would you say is the larger goal beyond documenting this history in a digital space? Are there plans for physical markers and/or plaques?

Jay: Our current phase of work is to continue documenting and researching more sites to add to the map. We launched the website with 100 fully researched sites and have almost 400 on our master database that will be added as researched. At the same time, we’re developing and giving walking tours, looking into the development of an app, and planning for an exhibition. At the moment, we’re not focused on physical markers or plaques due to our own capacity, the related expense, and the complexity of placing markers on private property. Still, it’s a great way to convey history; I love the fact that London has the pink plaque tours that are a guidebook in themselves.

Ken: The current website is, in essence, an online archive that can be used as a launching point for additional research and study. We see great potential in our research being used for interpretive and educational purposes: walking tour apps, podcasts, exhibitions, publications, and so on. With Stonewall 50 approaching in 2019, we want to make sure New York City’s LGBT place-based history is recognized by residents and tourists. We care about providing a visceral connection to a historic location. In the past, this type of research would be included in a report and not readily accessible to the public. But with social media, we can spread the word to a multi-generational, diverse audience cultivating interest in LGBT history. We’ll soon be looking at ways to use new technology to create some type of virtual plaque or marker that one can identify on a hand-held device. And we’re also still interested in the old-fashioned paper map that will highlight locations throughout the city.

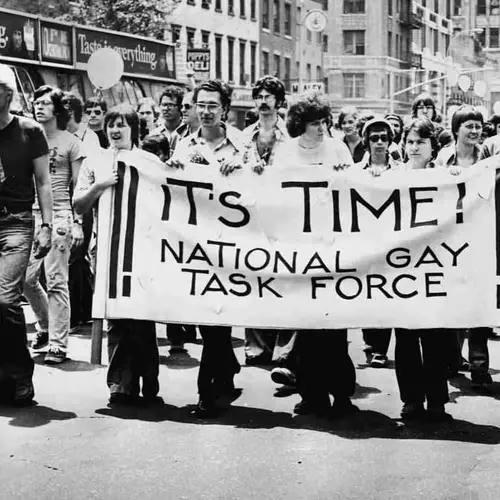

National Gay Task Force (now the LGBTQ Task Force) at the 1975 NYC Pride March. Photo by Peter Keegan. Source: LGBT History Archives.

National Gay Task Force (now the LGBTQ Task Force) at the 1975 NYC Pride March. Photo by Peter Keegan. Source: LGBT History Archives.

Why do you think the time is ripe right now to bring LGBTQ history to the forefront?

Jay: Given the political realities of the US right now it’s the perfect time to move this forward, but also Stonewall’s 50th anniversary is coming up in 2019.

Ken: It’s been ripe for over 25 years and now simply being harvested. The changes in LGBT visibility over the last 10 to 15 years have helped to provide a more comprehensive view of what shapes LGBT issues from politics, to culture, to history. And hopefully, our efforts will help provide a historical backdrop to current issues facing LGBT New Yorkers and Americans.

+++

RELATED: