INTERVIEW: Zoning and land-use attorney Michael Hiller fights to uphold the Landmarks Law

Michael Hiller is a zoning and land-use attorney who has represented community groups in seemingly impossible quests for about 20 years. His high-profile cases have often been against the Landmarks Preservation Commission, notably Tribeca’s iconic Clock Tower Building and new construction along historic Gansevoort Street, both of which are pending appeal by the defendants.

As one legal observer commented, “He has become an expert in the nuances of the Landmarks Law from a legal perspective. In court, he is very talented on his feet before a very hot bench, before judges who ask a lot of tough questions.” His successes have won him designation as a Super Lawyer every year since 2009 as well as the 2017 Grassroots Award from the Historic Districts Council. 6sqft recently visited Michael at his office to learn more about his work.

346 Broadway/the Clock Tower, via CityRealty

346 Broadway/the Clock Tower, via CityRealty

The Clock Tower, with its hand-wound timing mechanism, was designated an interior landmark in 1987. By law, interior landmarks have to be accessible to the public, as the Clock Tower had been for tours and as an art gallery. Developers who bought the building in 2014 expected to sell the clock tower as one of the condo conversions, which would have privatized it, making it inaccessible to the public, thereby invalidating its designation. Bring us up to date on that case.

We just won the appeal. The Appellate Court ruled that the Landmarks Preservation Commission committed clear error, and directed that the historic Clocktower Suite be preserved, along with the world-famous Tower Clock, including its mechanism.

Rendering of 46-74 Gansevoort Street, the buildings at the center of the legal matter. Via BKSK Architects.

Rendering of 46-74 Gansevoort Street, the buildings at the center of the legal matter. Via BKSK Architects.

Another prominent case is the proposed new construction on Gansevoort Street, in the Gansevoort Market Historic District, approved by LPC earlier this year. That suit contends that two of the approved buildings contradict the character and features for which the district was designated in 2003; and also that they contravene a restrictive declaration against the use of the property for office space. What’s going on with this?

Save Gansevoort is on appeal and we have an injunction pending appeal. That’s a positive sign. You can only get an injunction if the appellate division believes there’s a substantial likelihood of success on your appeal. In cases pending appeal, in my judgment less than five percent are successful. So I’m very happy about that. The argument has since been scheduled for December 14th in the afternoon.

The Merchants House Museum, via Wiki Commons

The Merchants House Museum, via Wiki Commons

The Merchants House case, a new nine-story hotel proposed right up against the 1832 Merchants House Museum, seems especially thorny. Tell us about it.

We intend to represent the Merchants House Museum and make sure that whatever is going on next door is not going to harm that building. I have some major concerns that any building erected next to the Merchants House is likely to cause severe damage, and I harbor this belief because I have reviewed the engineering reports that have been prepared. Naturally, that’s a major concern because the Merchants House is a precious jewel—it’s one of the oldest if not the oldest New York City landmark still in its original condition. It would be an absolute tragedy if that building were to be damaged.

Rendering of Jeanne Gang’s AMNH expansion, courtesy of Studio Gang

Rendering of Jeanne Gang’s AMNH expansion, courtesy of Studio Gang

Others?

Another project is Theodore Roosevelt Park—the Gilder Center, the Museum of Natural History’s expansion [west into the park]. That would destroy a whole bunch of trees and eliminate precious green space in violation of New York law. The Landmarks Preservation Commission issued permission under Section 25-318, which doesn’t necessarily mean approval of the project. That approval will be made by the lead agency under the State Environmental Review Board Quality Review Act, and to my knowledge that has not happened.

Rendering of Jeanne Gang’s AMNH expansion showing how the entry will appear alongside the park, courtesy of Studio Gang

Rendering of Jeanne Gang’s AMNH expansion showing how the entry will appear alongside the park, courtesy of Studio Gang

But independent of that approval process, the problem here is that this is really a series of buildings connected to each other in the middle of a park. Pathways go through the park into the museum from nearby streets. The museum obtained permission and a lease to occupy the space it currently occupies, and it got the right to use its “appurtenances” as well. When this lease was signed, “appurtenances” referred to pathways to the property, a term that was tantamount to an easement, a right of way. The rule in New York is that you can’t build on easements. So if they were to build onto any of these areas around the museum—and this expansion would do that—they would violate New York State law.

A Tribeca streetscape, via Chris Eason/Flickr

A Tribeca streetscape, via Chris Eason/Flickr

I’m also in a case for Tribeca Trust, an effort to extend three Tribeca historic districts. What’s interesting here is that the LPC is issuing determinations with respect to applications to extend historic districts without any rules, without any procedure, and the chair is often making them unilaterally and in the dark. So we filed an action or a proceeding against the LPC to require them to reconsider that application within the confines and within the framework of rules, procedures, and measuring criteria that are publicly disclosed. Not only was their action a violation of the Landmarks Law, but it’s a violation of the New York Administrative Procedure Law and may even be a Constitutional violation. We have a right in the United States to procedural due process, which allows you to be heard in matters of importance to you. Here, an application was made to the Landmarks Preservation Commission, which never afforded my client an opportunity to be heard.

They are a discretionary agency, though.

They have a lot of discretion. And this case makes clear that the greater discretion an agency has, the more important it is that they have rules, guidelines and measuring criteria to make decisions.

Photo via Public Domain Pictures

Photo via Public Domain Pictures

What do you look for in a case?

I look for something that has public policy importance, citywide, statewide or nationwide impact, and if it’s a landmark-protected property, that takes priority. I can’t remember the last time I brought a case that I didn’t think I could win. I always feel I can win a case if I’m on the right side of it. If I’m on the wrong side of it, I don’t want to win and so I won’t take those cases.

You’ve been practicing law for more than 25 years. What other areas have you been working in?

I represent people against insurance companies; I litigate against insurance companies on behalf of disabled policyholders and handle breach of contract, fraud, and breach of fiduciary-duty disputes. I also do construction litigation, so that when a building goes up and causes damage to an existing one, I represent property owners who have been damaged.

How did you get involved in land use and zoning?

When I started out, we got phone calls and complaints from residents once every three or four months concerned about over-development. When Mike Bloomberg became mayor, the calls increased to once every week or two. When de Blasio won, we started getting calls every day. Some of those callers claim that alleged political payoffs have impacted land-use and zoning decisions in their neighborhoods. Land use used to be 10 percent of my practice; it’s over 50 percent now. I used to handle one or two cases a year. Now I have 10.

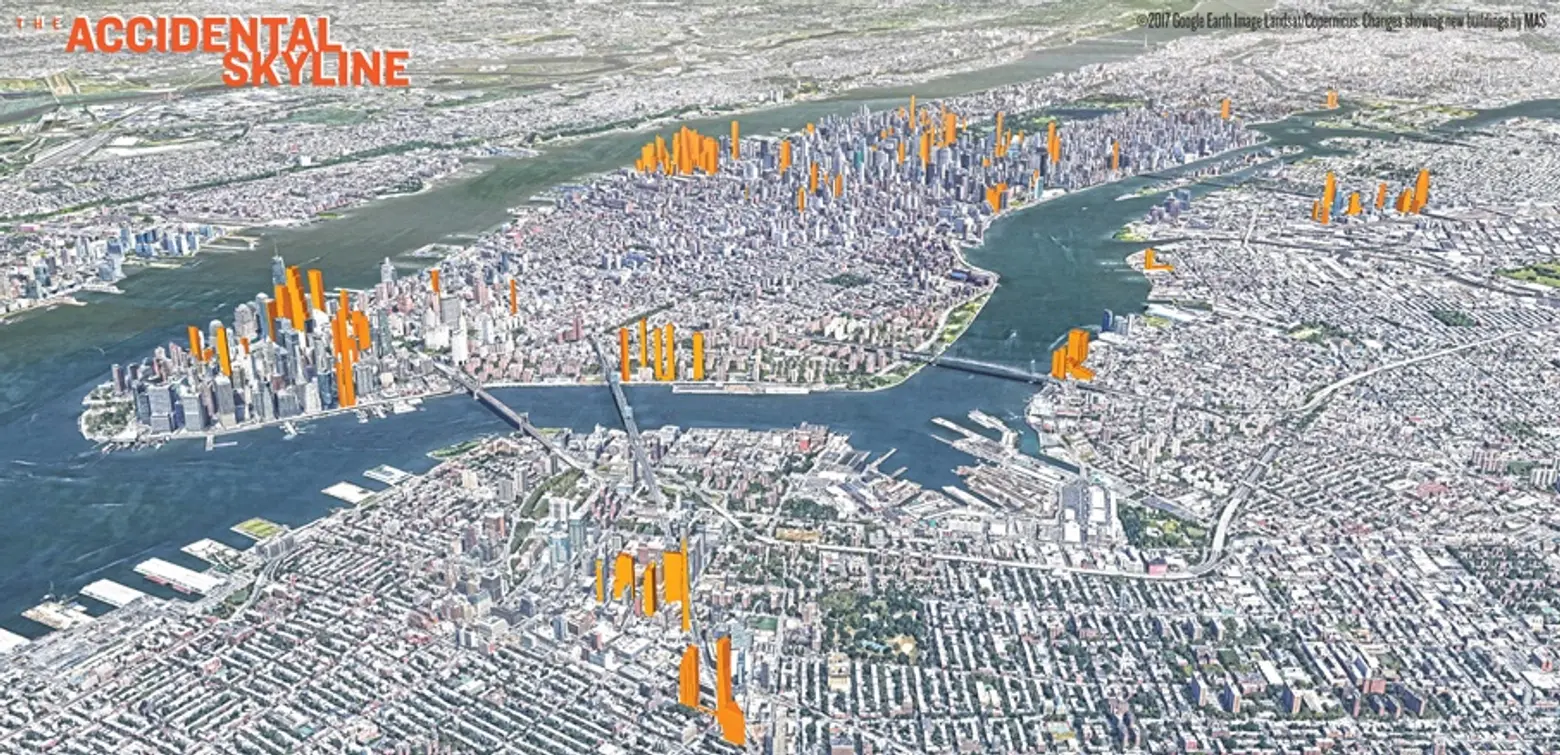

A rendering from the Municipal Art Society’s recent “Accidental Skyline” report showing the influx of supertalls

A rendering from the Municipal Art Society’s recent “Accidental Skyline” report showing the influx of supertalls

What are you concerned about in the near future?

I’m concerned about these super-tall towers that are going up all over the city. They are changing the orientation of our city. When you think of what makes New York great, it’s not the super-tall buildings; for me what makes New York City great is the eclectic mix of neighborhoods, the community fabric—Harlem, Brooklyn Heights, Park Slope. We also have Chinatown, Little Italy; we have a financial district, a very thriving commercial district, we have high-rise towers people can live in—we have this assortment of different neighborhoods with different scales, different heights and massing that makes New York City unlike any other in the world.

[Similar to what the Municipal Art Society is working on], my proposal is that we should have a moratorium, a suspension of buildings in excess of 210 feet with the caveat that if a developer wants to build bigger than 20 stories fine, but you have to do an environmental assessment to determine how much the massing and height of the building is going to impact the neighborhood and the urban planning of the city, so that we can maintain the soul of our City’s character.

+++

This interview has been edited for clarity.

RELATED:

Get Insider Updates with Our Newsletter!

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

Good article. I have worked with Michael Hiller on a landmark case. He’s an urban hero. He does a tremendous service for this city where human scale, vibrant and diverse neighborhoods, the need for light and air have all been threatened and relegated to the wishes of real estate developers and their private investment backers. As long as every square inch of New York including its air and light have been commoditized, our landmarks, our parks, our public spaces and our human needs for air and light and space are all at risk. New York is being packed with luxury condo’d towers for foreign billionaires who contribute little to this city. The fact that City Hall acquiesces and has given the keys to the kingdom to developers and their lobbyists shows how broken this system is. Where increasingly ordinary citizens fight costly battles to preserve New York’s history, culture and legacy is a great tribute to their advocacy and love for New York.