Latin in Manhattan: A look at early Hispanic New York

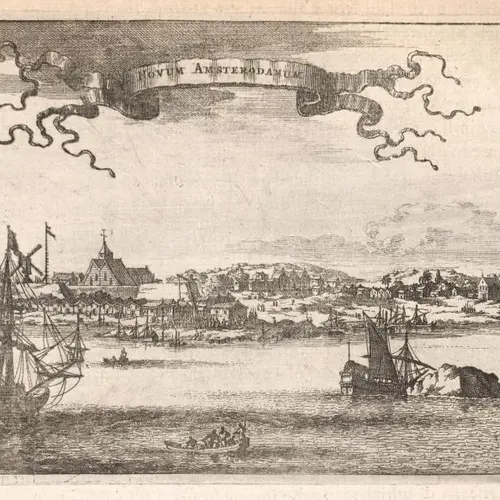

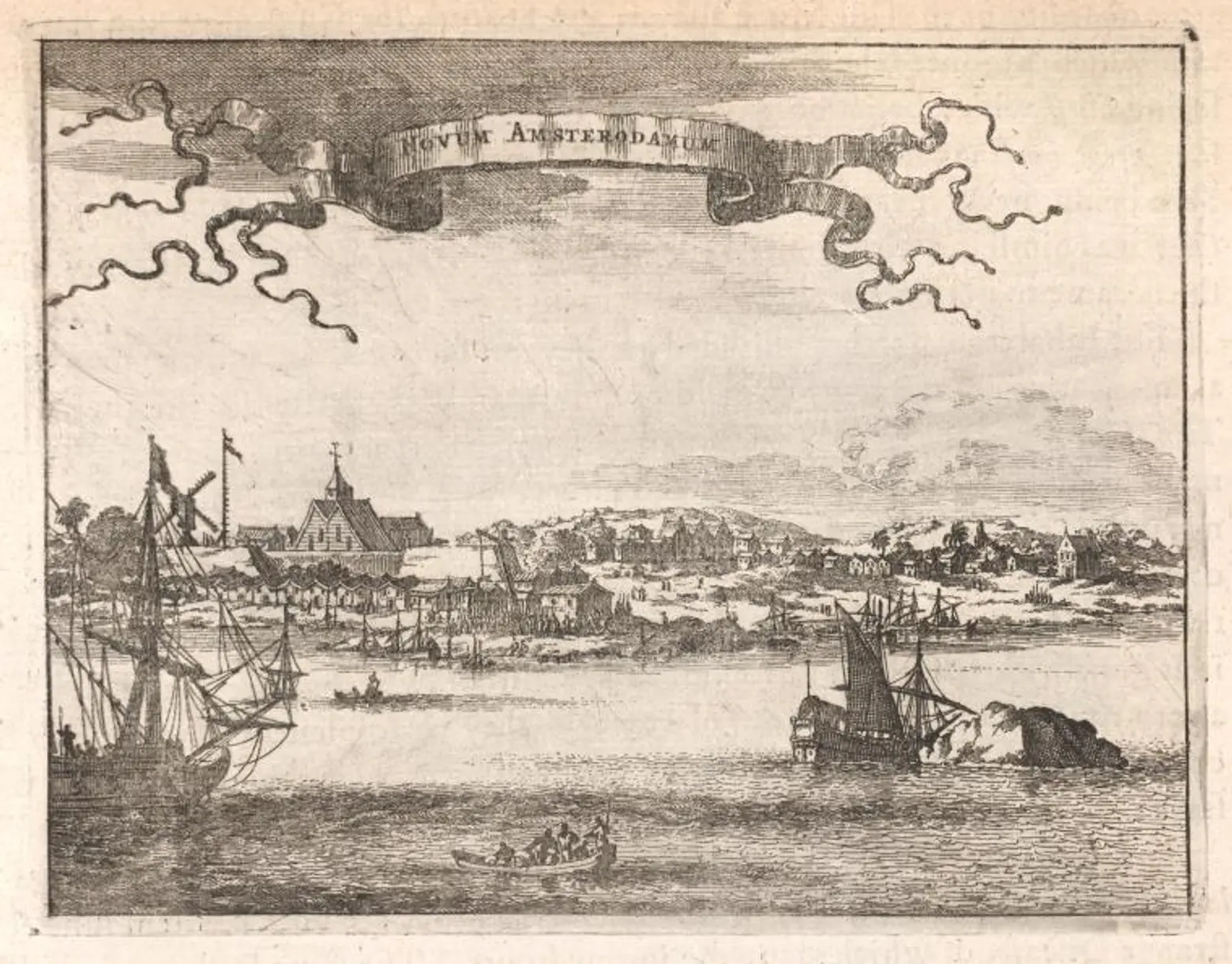

New Amsterdam in 1671, via Wiki Commons

Every year starting on September 15, we celebrate Hispanic Heritage Month to recognize the contributions and accomplishments of Hispanic Americans. Over 2.4 million New Yorkers, or nearly one-third of the city’s population, identify as Hispanic or Latino. The city’s thriving Latin community marks the most recent chapter in the history of Latin New York, which stretches over 400 years. Ahead, learn about early Hispanic New York, starting with the arrival of Juan Rodriguez, the first non-Native American person to live in New York City.

In the spring of 1613, Juan Rodriguez (also known as Jan Rodrigues), a free mixed-race Dominican man from Santo Domingo, became the first non-Native American person to live in what would become New York City. He arrived aboard a Dutch trading vessel, declined to leave with the rest of the crew, and stayed on until 1614, as a fur trader. Rodriguez’s settlement pre-dates the first settlers of New Amsterdam by a full 11 years, making him the first immigrant, the first black person, the first merchant, and the first Latino to live in New York City.

When the Dutch finally did come to stay, their colonial project was intimately connected to Latin America and the Spanish-speaking world. The Dutch West India Company, which administered New Amsterdam, was expressly formed in 1621 to wage war on the Spanish Empire in the Western Hemisphere.

The Company attempted to sack, steal or start settlements in the Spanish Americas. In fact, when the DWIC founded New Amsterdam in 1624, Manhattan Island was just one of a handful of West Indian Islands in its colonial portfolio: When Peter Stuyvesant arrived in the city in 1647, his official title was “Director-General of New Netherland, Curacao, Bonaire and Aruba.”

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. (1700). Nieu Amsterdam, at. New Yorck, via New York Public Library

New Amsterdam’s economic connection to these other islands in the Dutch West Indies brought the first Hispanic communities to the city, mostly by force. When New Amsterdam exported foods like flour and corn to Curacao, the city received slaves in return, who built its streets and docks, its roads, and its wall. Members of the city’s slave population who were Latin American were known as “Spanish Negros.”

New Amsterdam’s other early Hispanic community was a group of 23 Sephardic Jews who arrived in 1654 from Recife, Brazil. When the Portuguese sought to carry out the Inquisition in Recife, this small band of exiles headed for New Amsterdam, where Peter Stuyvesant sought to bar their entry. But, the directors of the DWIC overruled Stuyvesant, convinced that the Jewish immigrants held strong trading connections throughout the Spanish Empire, which would be helpful to the Company’s own goals.

This tiny Sephardic community established Congregation Shearith Israel, the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue, which was the first Jewish congregation in North America, and the only one in New York City until 1825.

Apart from these two groups, New Amsterdam was staunchly anti-Spanish, and virulently anti-Catholic, a prejudice that survived under English rule. In British Colonial New York, priests were barred from the colony, and “papists” could not vote.

The American Revolution changed everything. Spanish diplomats, soldiers, and merchants arrived in New York, and the revolutionary zeal that made the United States sent an anti-colonial spark around the Latin world, which drew Caribbean revolutionaries to the city.

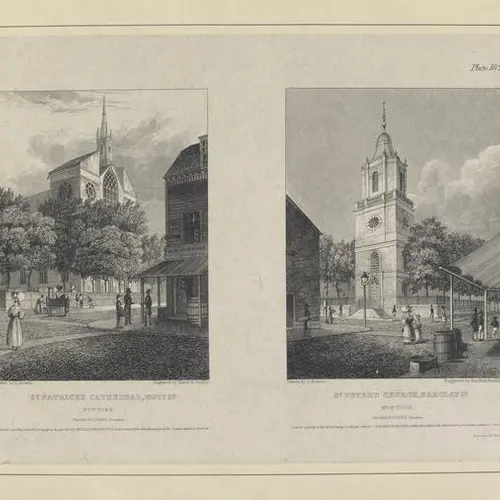

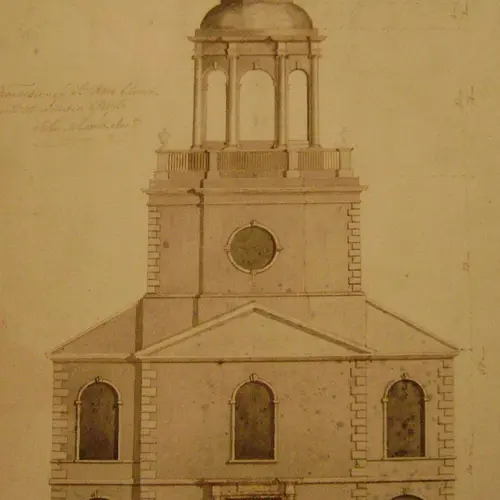

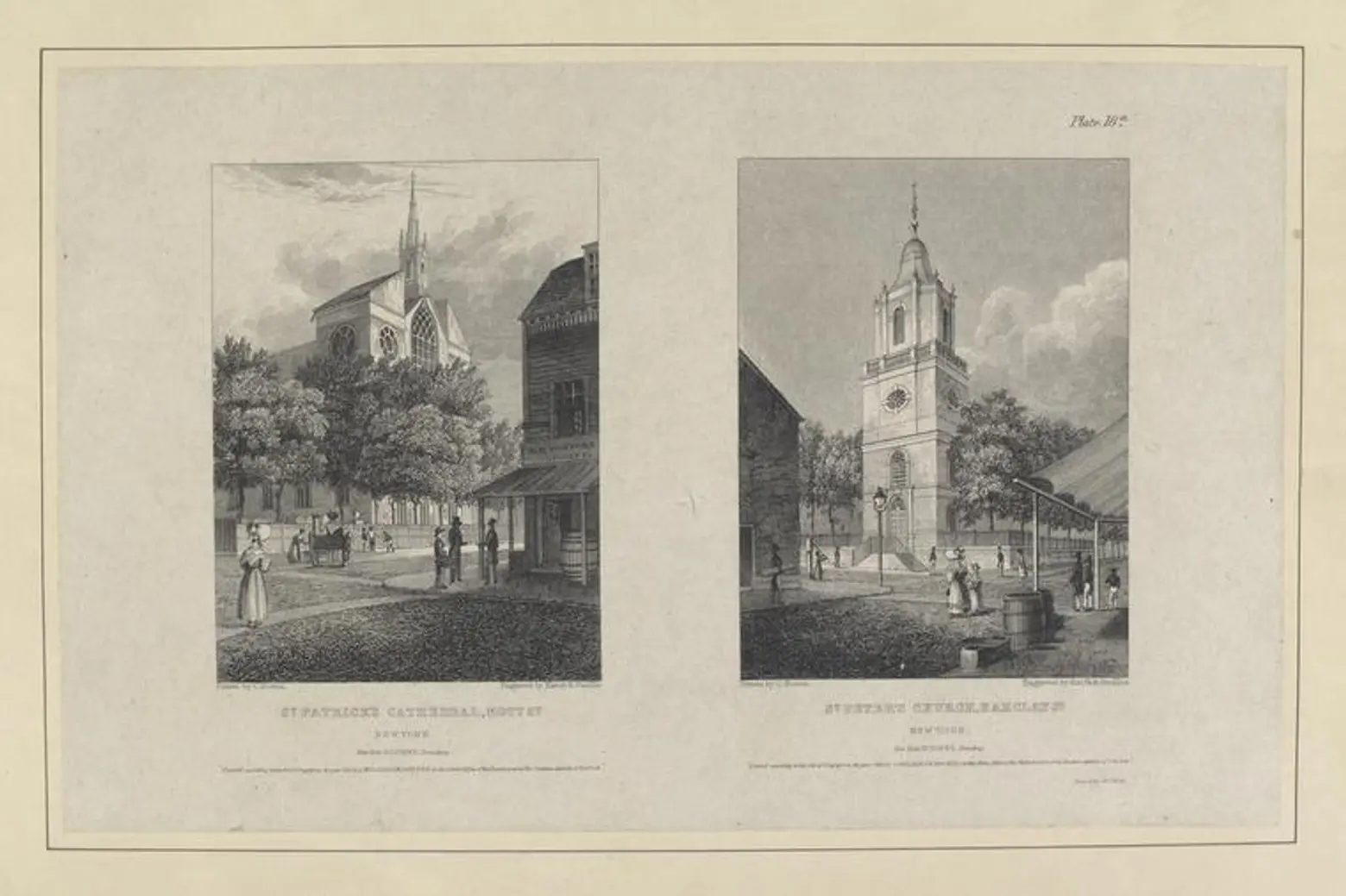

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. (1831). Plate 18th. St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Mott St. New York; St. Peter’s Church, Barclay St. New York, courtesy of the New York Public Library’s Digital Collection

Because the Spanish had rendered economic and military aid to the Continental Army, Spaniards, and “papists” were welcome in post-revolutionary New York City. In 1785, the community set about building the city’s first Catholic church, St. Peter’s, on Barclay Street.

In 1784, at the very same moment, the Spanish were establishing their community in New York, Francisco de Miranda, a central figure of the Latin American independence movement, arrived in the city, seeking support for his goal to secure “the liberty and independence of the Spanish-American Continent.”

It was in New York, he wrote, that this project formed. He returned to the city in 1806 and recruited 180 New Yorkers to liberate Venezuela. Though the campaign failed, it inspired other revolutionaries including Simon Bolivar, who arrived in New York the following year.

Soon, rebellions spread across Latin America, so that by 1825, Spain had lost all of its Latin American colonies except Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the Philippines. New York merchants heartily supported the rebellions, because they dreamed of vast sugar fortunes to be had if the Spanish could be eliminated from the region entirely.

While New Yorkers had been refining sugar since the early 18th century, 1825 also marked a watershed in the city’s relationship with that industry, because the newly opened Erie Canal made New York the fulcrum of trade between the Midwest, Europe, and the Caribbean.

By the 1830s the sugar trade centered in New York was so prolific that by 1835, Cuba was the United States’ third-largest trading partner, and a significant Cuban community had made New York home.

In 1828, the Cuban community established the city’s first Spanish-language newspaper, Mercurio de Nueva York. In 1830, merchants organized the Sociedad Benéfica Cubana y Puertorriqueña to promote trade between the United States and the Caribbean. By 1850, there were 207 Cuban immigrants living in Manhattan. A decade later, the community had grown to over 600 people, living in affluent and middle-class neighborhoods in Lower Manhattan, Greenwich Village and the blocks between Union and Madison Squares. While merchants had established the backbone of New York’s Cuban community, it was Cuba’s revolutionaries and literati that made New York the primary staging ground for the building of the Cuban nation.

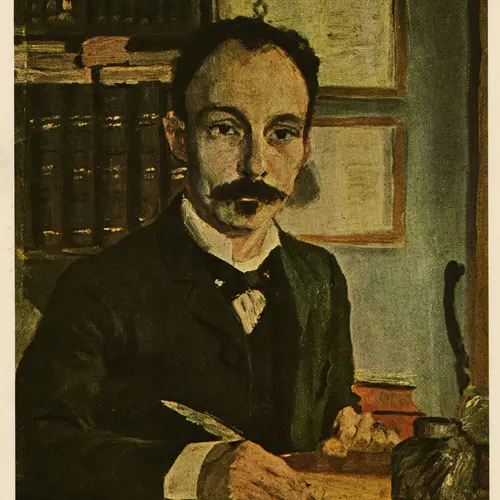

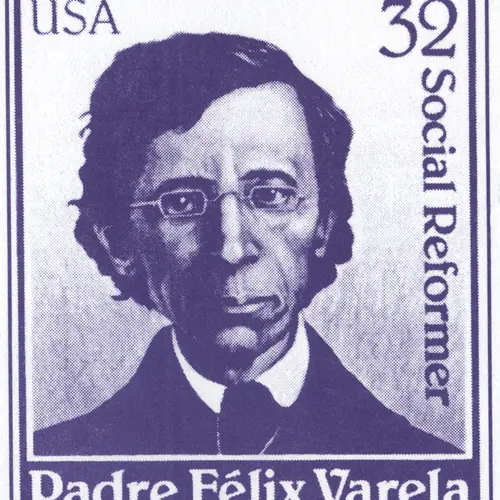

Felix Varela, via Wikimedia

The Cuban revolutionary Felix Varela was exiled to New York in 1823. In the city, he became both a separatist leader and a religious one. He was appointed to a post at St. Peters and rose to become vicar-general of the New York Diocese. In the meantime, he published the revolutionary magazine El Habanero and smuggled it down to Havana.

When the Cuban flag flew for the very first time, on May 11, 1850, it flew in New York, hoisted aloft the offices of the New York Sun in Lower Manhattan, where the editorial staff was in favor of a Cuba free from Spain, but annexed to the United States. The flag was designed by the ex-Spanish Army Officer, and Cuban separatist, Narciso Lopez. Lopez arrived in New York in 1848, and New Yorkers joined him on all three of his attempts to liberate Cuba by force.

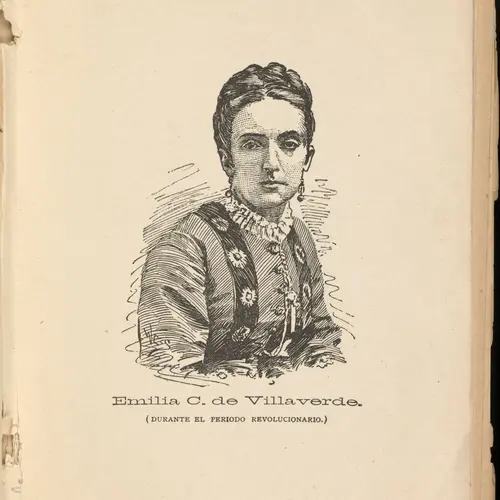

In 1868, Cubans and Puerto Ricans rose up against Spanish rule. In Cuba, the conflict lasted 10 years and sent a stream of refugees to New York. Those refugees, in turn, supported the fighters back home. For example, Emilia Cassanova turned her Hunts Point home into a hotbed of militant activity. In 1869, she founded Liga de Hijas de Cuba (League of the Daughters of Cuba), which smuggled arms and ammunition to partisans on the island.

By 1870, there were over 2,700 Cuban-born New Yorkers, the largest contingent of a Hispanic population hailing from Spain and Latin America that numbered 3,600. New York’s Cuban refugee manufacturers threw their hats into New York’s booming cigar trade, establishing hundreds of factories. These enterprises drew working-class Cubans and Puerto Ricans to New York who formed communities in Manhattan and Brooklyn.

The cigar workers formed the grass-roots base of Jose Marti’s Cuban Revolutionary Party (PRC). Marti arrived in New York in 1880 and spent the next 15 years in Manhattan carrying out his life’s work: the creation of an independent Cuba. From his office at 120 Front St., Marti published the revolutionary newspaper Patria, and composed articles for New York papers, as well as those in Mexico and Argentina. In 1887, Marti helped found the Spanish-American Literary Society of New York, at 64 Madison Avenue. The club brought together writers of various nationalities.

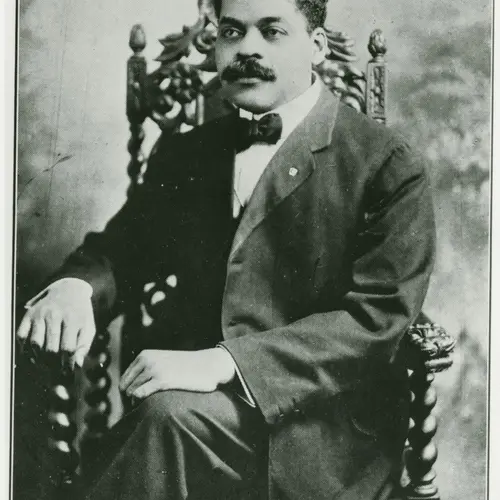

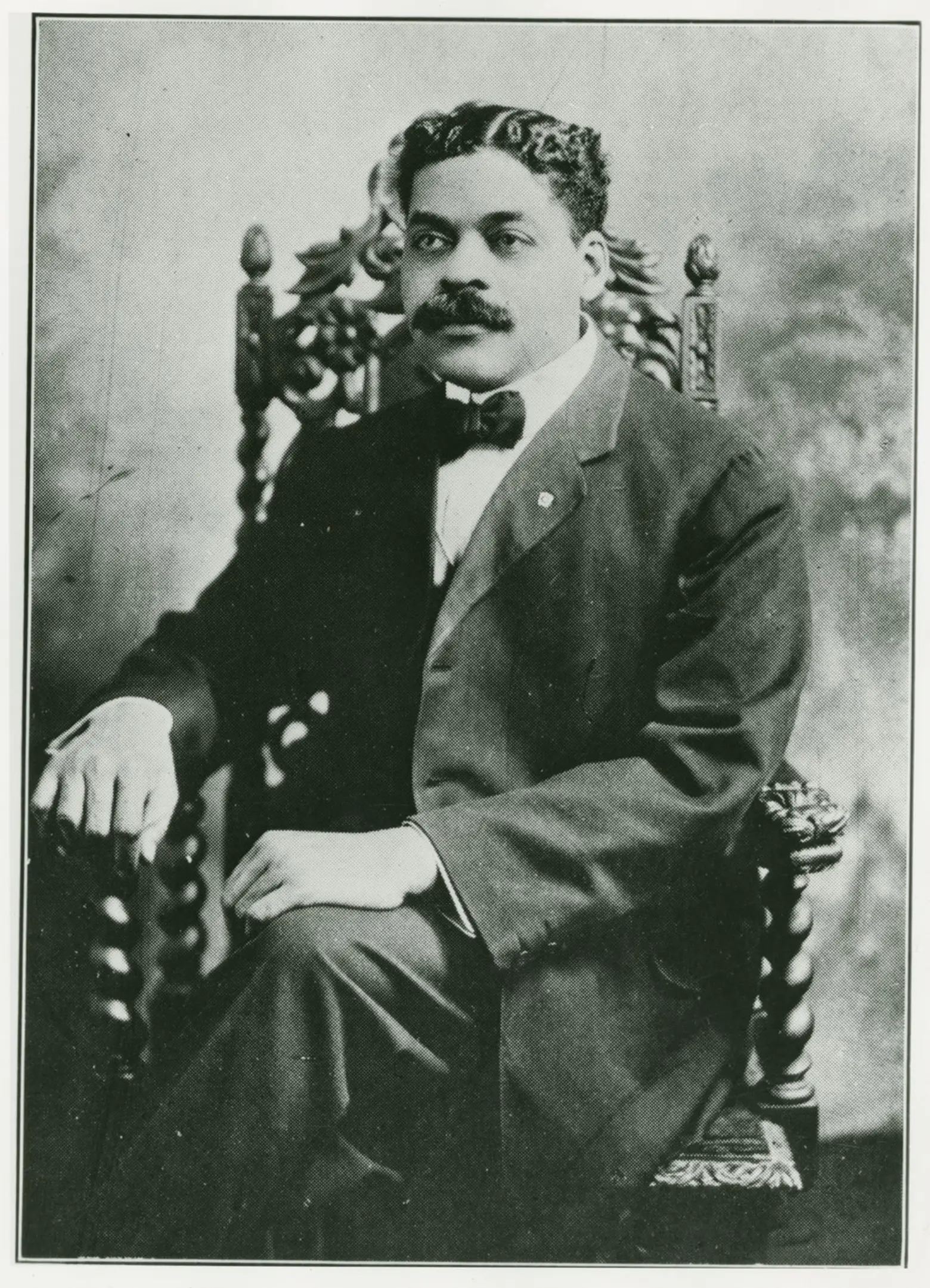

That transnational, pan-Hispanic ethos was also evident in the PRC. The party had a Puerto Rican section, and activists formed clubs to foster unity between Cubans and Puerto Ricans in the Party. For example, the Puerto Rican immigrant Arturo Schomburg, the great writer, historian, bibliophile, and key figure of the Harlem Renaissance, who arrived in New York at the age of 17, and whose collection of Afro-Americana would become the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library, founded Las Dos Antillas (The Two Islands) a club that advocated the independence of both islands.

Arturo Schomburg, ca. 1900s via Wikimedia

The Two Islands went to war with Spain again in 1895. When the US entered the fray in 1898, battleships constructed in Brooklyn’s Navy Yard carried soldiers down to the islands to fight. One hundred days after the Americans first intervened, the war ended. Instead of Cuba Libre, the islands were now subject to the United States. The US had acquired Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, and had secured the right to intervene in Cuban affairs.

American intervention in Latin America, and particularly the Jones Act, which made Puerto Ricans American citizens in 1917, set the stage for large-scale Latin immigration to New York City, a process that continues to enrich the city to this day.

Editor’s note: The original version of this story was published on August 8, 2018, and has since been updated.

+++

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

RELATED: