Lincoln Center: From Dutch enclave and notorious San Juan Hill to a thriving cultural center

The glossy cultured patina of Lincoln Center reveals nearly nothing of what the neighborhood once was, and New Yorkers, accustomed to the on-going cycle of building and demolition, have likely forgotten (or never knew) about the lively San Juan Hill neighborhood that was demolished to make way for the famous cultural center. Any such development dating from the 1960s wouldn’t be without the fingerprints of the now-vilified Robert Moses, who was more than willing to cut up neighborhoods both poor and wealthy in the eye of progress.

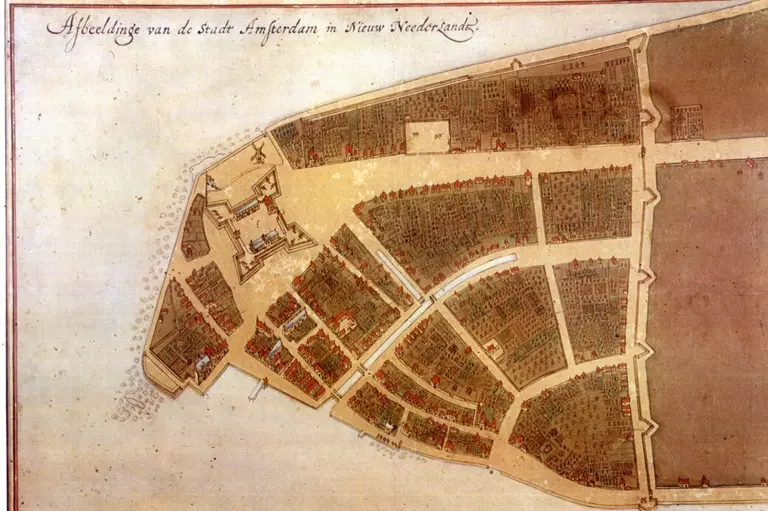

While the tough reputation of Hell’s Kitchen on the West Side just south of Lincoln Center is well-documented in the history of the Irish diaspora, the history of San Juan Hill was mostly erased by a single sweep of urban planning, by nature of simply no longer existing. As New York City expanded and industrialized, immigrant communities moved northward. African-Americans were also part of this movement, even pre-Civil War, along with their neighbors the Irish, Italians, and Germans. Originally, all groups were mixing and getting in trouble down in Five Points. Harlem’s reputation as the center of African-American culture wouldn’t exist without the gradual northward movement of their community through the 1800s. After Five Points, the population moved into Greenwich Village, then to the Tenderloin in the streets between the 20s and 30s, then to Hell’s Kitchen. The area that’s now Lincoln Center was the logical next step, originally settled by the Dutch as an enclave by the name of Blooming Dale with its leafy aristocratic country homes.

The name San Juan Hill possibly references a famously bloody 1898 battle in Cuba during the Spanish-American War, which included the Buffalo Soldiers, an all-black regiment who were instrumental in taking the hill for the Americans. By the end of the 19th century, San Juan Hill was home to the majority of the black population in New York City. According to Marcy S. Sacks in the book “Before Harlem: The Black Experience in New York City Before World War I,” it was also one of the most crowded in the city: “One block alone housed upward of five thousand residents.” Like other immigrant neighborhoods before, it was the scene of vice as well as everyday living. Mary White Ovington, a white reformer during the early 1900s speaks of the contradictory conditions:

There were people who itched for a fight, and people who hated roughness. Lewd women leaned out of windows, and neat, hardworking mothers early each morning made their way to their mistresses’ homes. Men lounged on street corners in as dandified dress as their women at the wash tubs could get for them; while hardworking porters and longshoremen, night watchmen and government clerks, went regularly to their jobs.

Frequent clashes between Irish residents in Hell’s Kitchen and black residents in San Juan Hill inspired the setting of “West Side Story,” and the opening scenes of the film were shot there before the demolition (the movie was released in 1961).

Despite the depravity (or perhaps as a result of it), the neighborhood also became a locus for benevolent associations like the YMCA (founded specifically for African-American men), the Colored Freemasons, and the Negro Elks and numerous black churches. Collectively, these institutions served to assist migrants coming from the south. Culturally, the area was booming, becoming the city’s destination for live jazz. Among the clubs was The Jungle’s Casino where pianist James P. Johnson wrote a song to go along with the “wild and comical dance” of off-duty dock workers.” Together, this became the Charleston, which took the nation by storm. San Juan Hill was also home to jazz great Thelonius Monk who moved to the neighborhood at age 4 in 1922. According to Untapped Cities, “residents remember him as an eccentric man who walked around beneath their windows singing to himself–no doubt composing some of jazz’s most memorable melodies.” Today, Jazz at Lincoln Center continues the neighborhood’s illustrious music heritage, albeit in a much swankier venue in the Time Warner Center.

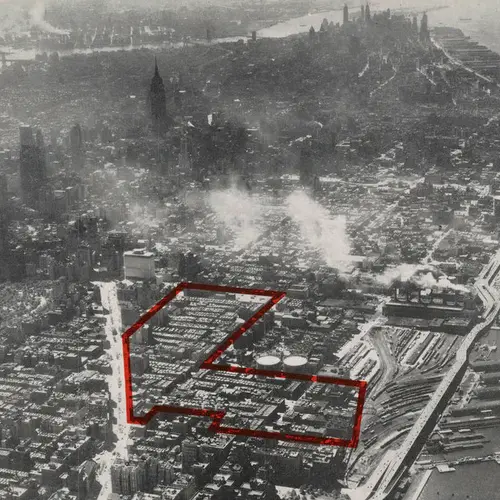

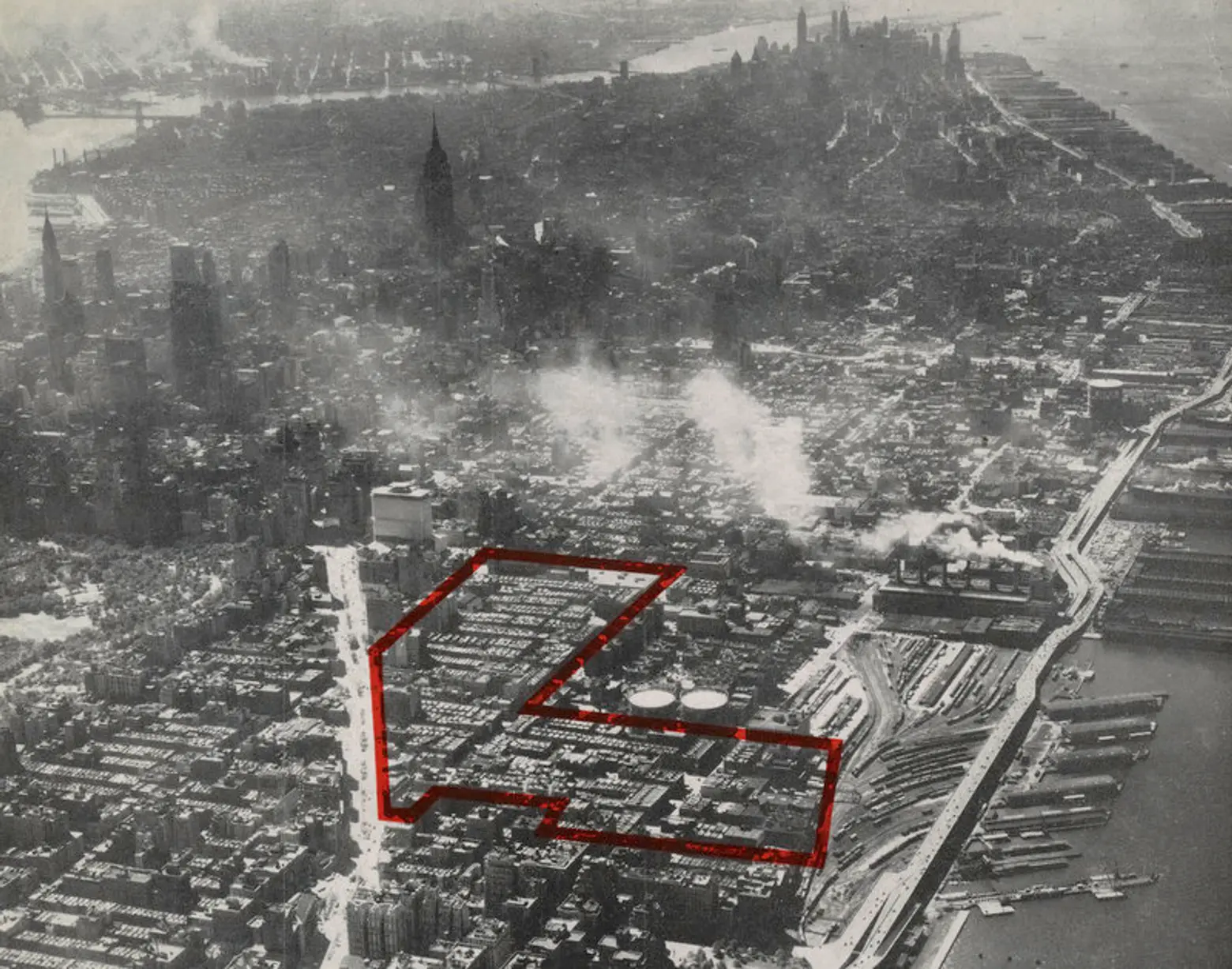

In 1940, the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) named San Juan Hill “the worst slum section in the City of New York,” setting the stage for urban renewal plans. Though Lincoln Center went up in the 1960s, demolition of San Juan had already begun shortly after WWII. An area between 10th and 11th Avenues was first to go, becoming public housing project Amsterdam Houses which still exists. The rest of the neighborhood went down in the 1950s.

Cover of the “Lincoln Square Slum Clearance Plan.” Image from New York Public Library.

Cover of the “Lincoln Square Slum Clearance Plan.” Image from New York Public Library.

The initiative for the Lincoln Center arts complex was impelled forward by John D. Rockefeller, who also raised more than half of the $184 million needed to construct the development. The Metropolitan Opera had been seeking a move from its location on Broadway and 39th Street since the 1920s, and the new arts complex was the perfect match for both Robert Moses and the opera company. The Metropolitan Opera actually sued to have their original building demolished to prevent potential competition if another opera company moved in to the 39th Street hall. Despite protest based on its architectural merit and history, the building was razed in 1966 because it was not landmarked. It has since become a prime example for preservationists of what should still be standing, along with the original Penn Station which was demolished in 1963.

With the New York Philharmonic also seeking a new space following the end of a lease at Carnegie Hall (which was also planned to be demolished but saved by the city of New York) and Fordham University’s consolidation at the southern end of the Lincoln Center plot, the stage was set. The New York City Ballet, the City Opera and the Juilliard School followed suit.

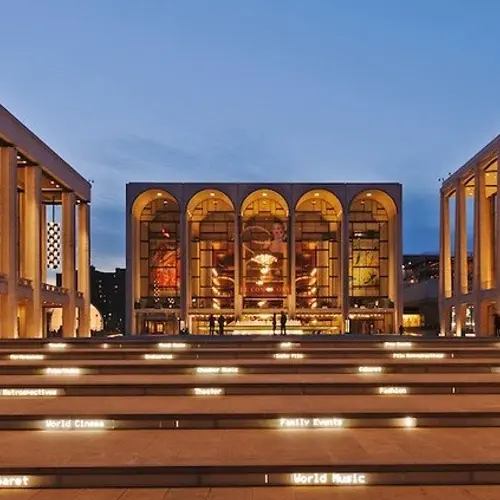

The main buildings, which include the opera house, the New York City Ballet, Avery Fisher Hall, Alice Tully Hall, David H. Koch Theater, and the Juilliard School, stayed as they were built until 2012 when a major redevelopment plan commenced. Architecture firms Diller Scofidio + Renfro, FXFOWLE Architects and Beyer Blinder Belle modernized the Lincoln Center complex, focusing much on improving pedestrian access and streetscape.

A large over-street plaza on 65th Street that once connected Juilliard, the Walter Reade Theater and the School of American Ballet to the main plaza was removed. In its place, along 65th Street was built a unique building with a curved, green roof open to visitors in the summer. Inside, there is the Elinor Bunin Monroe Film Center, the great Indie Food & Wine cafe, and Lincoln Ristorante by Jonathan Benno. The Robert Moses-style taxi and car drop off in front was moved below-grade to provide better pedestrian access from the street to the main plaza. Alice Tully Hall was completely redone, with a glass entrance that now also houses Marcus Samuelsson’s American Table. And to the chagrin of some, the famous fountain was modernized.

Despite all these changes to San Juan Hill since the mid-20th century, there are still some architectural remnants from an earlier era—holdouts if you will–that resisted demolition. At 152 West 66th Street is the Church of the Good Shepard was built in 1887 by J. Cleveland Cady, the architect who designed the original Metropolitan Opera house. It continues to serve as a church today and as a venue for intimate classical concerts throughout the year. In 2004, Christopher Gray of the New York Times called it “one of the most impressive small religious buildings in New York—and looks no worse for wear than the nearby middle-aged monoliths.” The neo-Gothic Hotel des Artistes on West 67th Street was the centerpiece of an artist’s colony, permanently remembered in the National Register of Historic Places as the West 67th Street Artists’ Colony. The Church of St. Paul the Apostle on West 59th Street and 9th Avenue, built between 1876 and 1884, also still stands.

Via Flickr cc

Via Flickr cc

As for Robert Moses, his end was coming soon with widespread opposition to LOMEX, an expressway that would have cut through Soho and Little Italy, along with his widely publicized feud with economist Jane Jacobs. It took a long time for Lincoln Center to really take hold as a cohesive neighborhood. Until the late 1990s and 2000s the area was fairly sparse, save for a Tower Records on the corner of 66th Street and Broadway. Nearby Columbus Circle was also run down and graffiti-ridden. The arrival of Sony Theaters at 68th Street heralded the development that was to come, transforming the Lincoln Center area into the busy residential and cultural corridor it is today. Luxury high rises dot the once low-rise landscape, stretching from Central Park West to Riverside Park, drastically changing the view and ushering Lincoln Center into the 21st century.

RELATED:

- MAP: Here’s what the NYC subway system looked like in 1939

- Diego Rivera’s psychedelic Rockefeller Center mural was destroyed before it was finished, 1934

- This never-built Washington monument would have been the city’s tallest structure