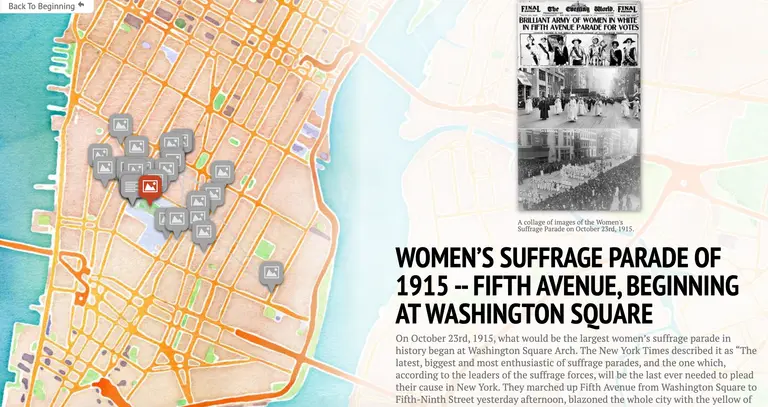

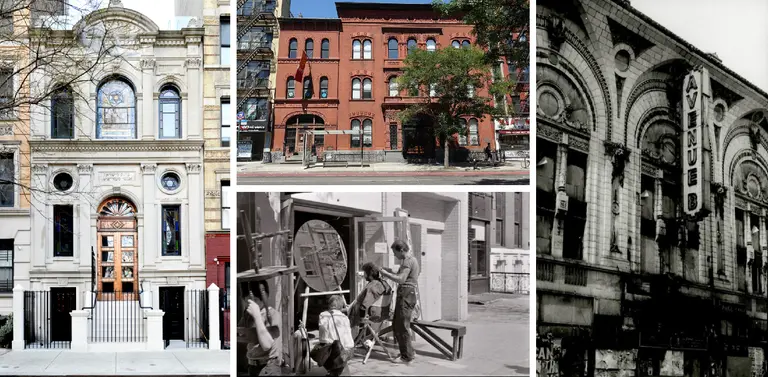

Looking back at New York’s ‘Summer of Love’ and the birth of the East Village

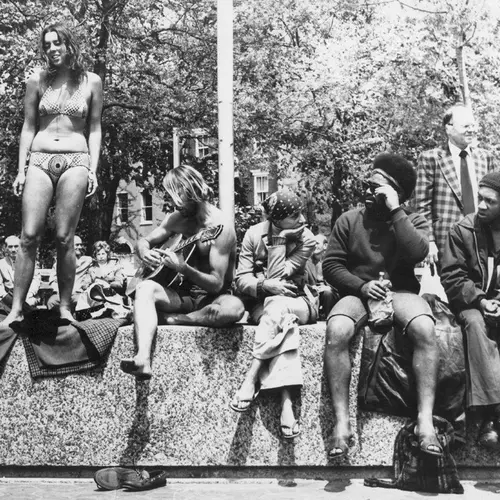

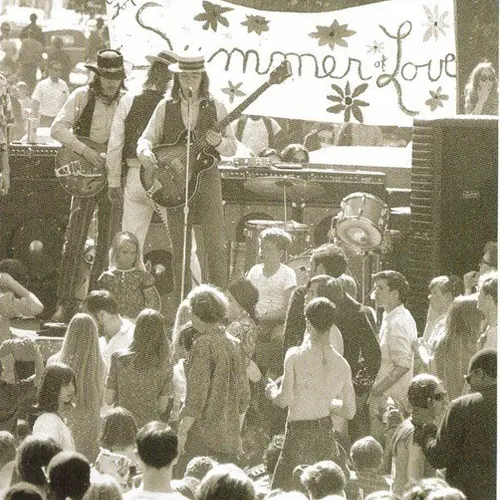

Hippies singing and playing music in Washington Square Park in the late 1960s. Photo: Peter Keegan

It has been 50 years since 1967’s “Summer of Love” when young people from around the world flocked to San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district and to other urban neighborhoods, including New York’s East Village, to trip out at psychedelic dance parties, sleep in city parks, and live and do whatever they pleased. While the hippie subculture was already flourishing prior to the Summer of Love, by mid 1967, hippies and their music, style, and communal way of life had caught the attention of the mainstream media and as a result, reached a critical mass of young people who were now eager to ditch their suburban homes to “turn on, tune in, and drop out.”

Reactions to the Summer of Love in New York were predictably mixed. An estimated 50,000 young people descended on the city to join the movement, but many New Yorkers, including longstanding residents, police officers, and politicians, had little interest in spending the Summer of Love soaking up the good vibes. In the end, the city’s Summer of Love saw as much conflict and violence as peace and love, and debates about rental prices, real estate values, and the gentrification of the Lower East Side were all part of the conflict.

Hippies gather in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury. Image via haightashburysanfrancisco.com

Hippies gather in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury. Image via haightashburysanfrancisco.com

A tale of two cities

In many respects, the Summer of Love was a tale of two cities. In San Francisco, where the idea for the Summer of Love originated, over 100,000 young people from around the world flocked to the city’s Haigh-Ashbury neighborhood and to the nearby San Francisco State and Berkeley university campuses. By the time they arrived, however, the Council for the Summer of Love, which was comprised of an eclectic group of musicians, actors, and activists, was well prepared for the onslaught. Beyond organizing happenings of all kinds, the Council had already set up a free medical clinical, organized housing, arranged for free food distribution, and even troubleshot potential sanitation problems in city parks. They did this with the support of local residents and even church groups.

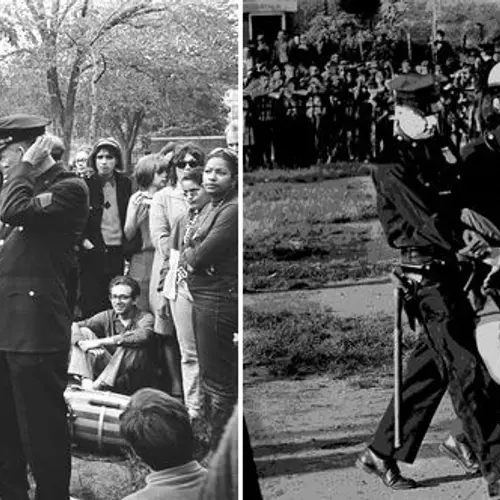

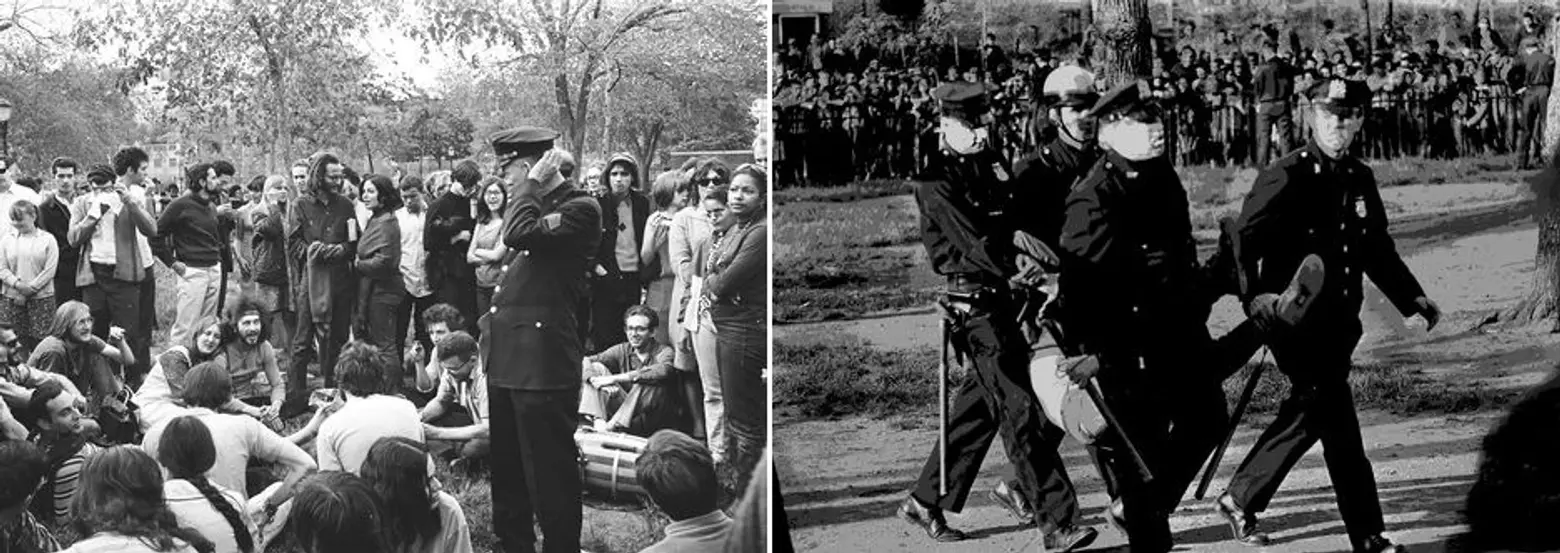

The scene at Tompkins Square Park on Memorial Day, 1967. Image via lorenbliss

The scene at Tompkins Square Park on Memorial Day, 1967. Image via lorenbliss

In sharp contrast, New York’s Summer of Love got off to a rocky start on Memorial Day Weekend when a group of hippies clashed with local residents and police in Tompkins Square Park. As reported on June 2, 1967, in the New York Times, police swarmed the park “as tensions between hippies and anti-hippies rose against the backdrop of protest music in Tompkins Square Park.” The over 200 officers who rushed to the scene were apparently there to restore to peace after residents and anti-hippie protesters complained that 200 hippies had assembled in the park without a permit and “were playing their bongos too loudly and too constantly.” By the end of the day, dozens of injuries had been incurred by police, protestors, and hippies, over thirty people had been arrested, and one young woman had been stripped naked by a group of anti-hippie protestors on a street corner just outside the park. Unfortunately, such scenes of conflict and violence would continue to unfold throughout New York’s Summer of Love, even as some public leaders sought to maintain the peace.

Drugs, noise, and soaring rents in the new “East Village”

While the Summer of Love was by no means confined to a single neighborhood, like San Francisco, New York’s rendition had a clear epicenter—the East Village and specifically, St. Mark’s Place between Second and Third avenues. But if the Summer of Love had a center, it likely had more to do with business savvy than destiny.

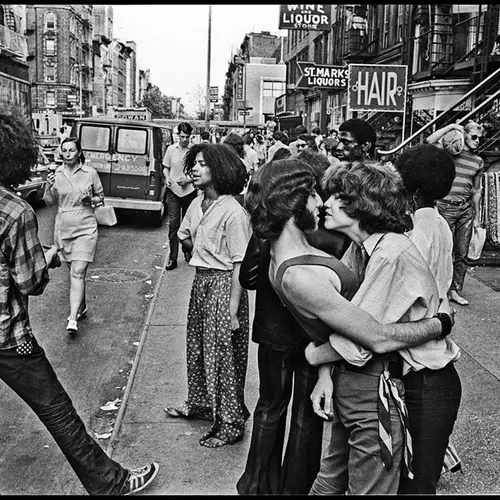

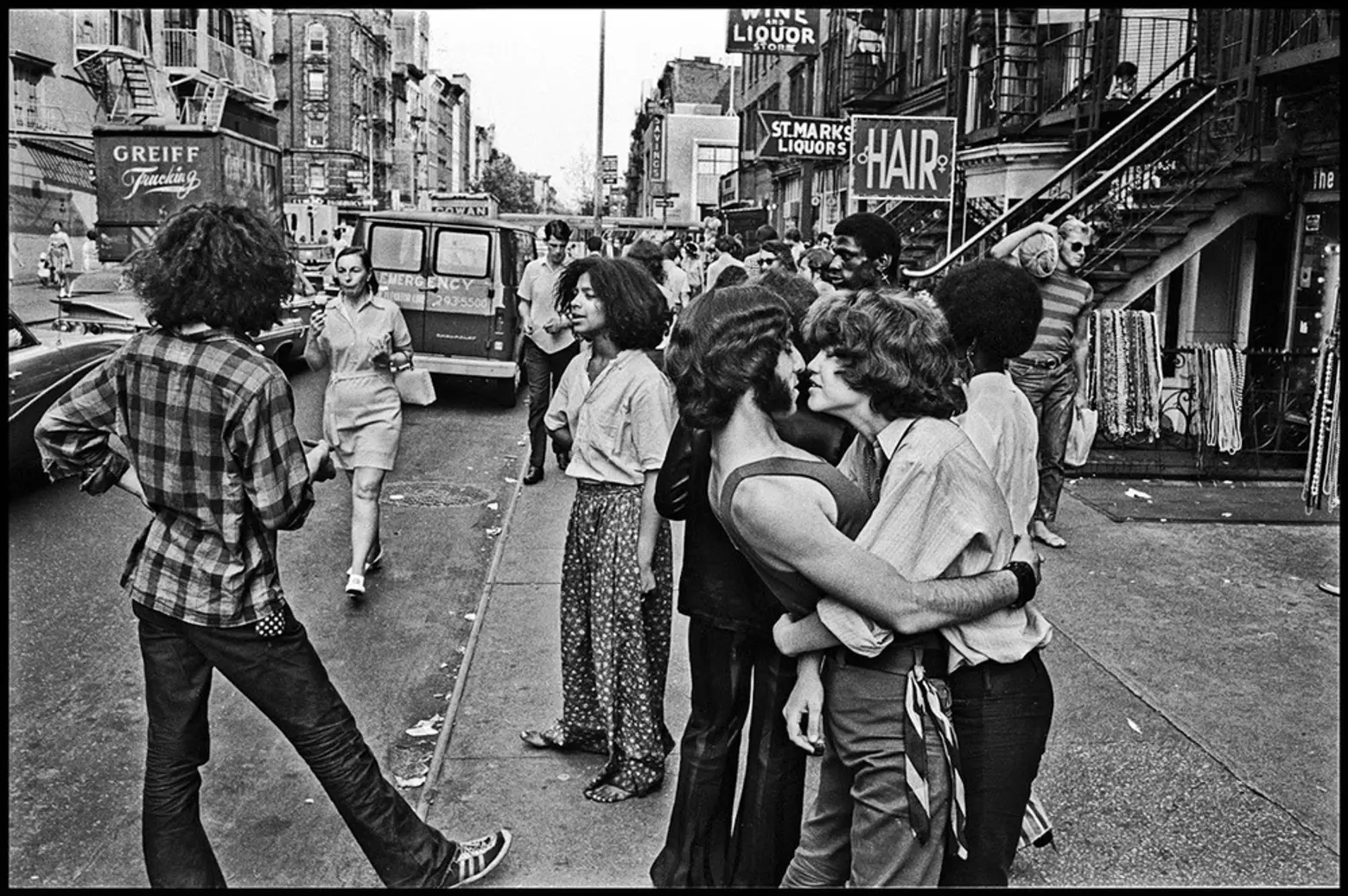

St. Marks Place, 1968. Image by George Cohen via EV Grieve

St. Marks Place, 1968. Image by George Cohen via EV Grieve

While some merchants despised the hippies, many others welcomed the influx of affluent youngsters. On St. Mark’s Place, merchants even sought to create a “night mall” by closing the street to traffic from 7:00 pm to midnight. One reporter described the scene as follows: “Raindrops and flowers gently pelted a thousand people who jammed the pavement, stoops and fire escapes of St. Mark’s Place last night for a psychedelic dance party.” But as the article further observed, “below the flow of balloons, daisies, lights and music came grumbles.” Many older Ukrainian, Italian, and Jewish residents felt that local merchants were handing over their neighborhood to the new arrivals, and even some longstanding business owners were upset. Jerry Polk, the manager of the St. Mark’s Baths, complained that he was simply “too old for this stuff.”

If many residents and even some business owners were upset about the influx, it was not without reason. While the Summer of Love certainly brought increased business to the Lower East Side, it also resulted in soaring rents and a strategic rebranding of some parts of the neighborhood. In Selling the Lower East Side, housing historian Christopher Mele observes that from May to June 1967, an estimated 2000 hippies moved into old tenements adjacent to Tompkins Square Park. At the same time, rental prices soared throughout the neighborhood as demand for housing increased and leases were turned over more quickly. In the summer of 1967, properties as far east as Avenues C and D were impacted by the hippies’ mass arrival and accompanying demand for housing.

In the end, most of the money invested in the Lower East Side during the Summer of Love vanished as soon as the hippies started to retreat, but there was one permanent change. Following the summer of 1967, the western most blocks of the Lower East Side between Houston and 14th Street would be referred to as the “East Village” rather than Lower East Side. According to Mele, at the time, “Landlords, developers and real estate firms sought to channel the growing popularity of the East Village as a means of attracting a broader and more equivocal category of upscale middle-class residents.”

The end of the Summer of Love and pilgrimage Upstate and beyond

Unlike San Francisco, where the Summer of Love vibe appeared to linger for years, in New York, the Summer of Love really was just a summer. Following months of clashes and verbal conflicts with local residents, police, and politicians, in October 1967, tragedy struck when a hippie couple was found murdered in a basement boiler room of a tenement building at 169 Avenue B. One victim, Linda Fitzpatrick, was the 18-year-old daughter of an affluent Connecticut couple. Groovy, a well-known local drug dealer who had a reputation for giving his LSD away for free, was also found dead at the scene. The highly publicized murder not only resulted in a massive moral panic amongst suburban parents who were soon contacting the NYPD to track down their missing children but also symbolically marked the end of New York’s Summer of Love.

While some hippies stayed, traded their Jesus sandals for sturdier footwear, and helped turn the East Village into North America’s punk rock capital, others headed west to the more peaceful Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco or “back to the land” in upstate New York, Vermont, or Massachusetts. Whether one stayed and fled to the countryside, however, cheap real estate was certainly on the hippie generation’s side.

Those who stayed in New York watched real estate values plummet over the next two decades, especially in the East Village and Lower East Side, which enabled many former hippies to buy properties at rock-bottom prices. For those who headed to greener pastures, there were also deals to be found. Activist Senator Bernie Sanders still boasts about purchasing over 80 acres of land in Vermont for a mere $2500 in the mid-1960s, and he wasn’t alone. Even as the hippies were seeking peace and love, they were making smart real estate deals, which would ultimately transform both urban neighborhoods and rural destinations across the United States.

RELATED: