Mapping the Evolution of the Lower East Side Through a Jewish Lens, 1880-2014

Image courtesy of MNCY

Long considered the capital of Jewish America, this overpoweringly cramped neighborhood was considered by many to be the greatest concentration of Jewish life in nearly 2,000 years.

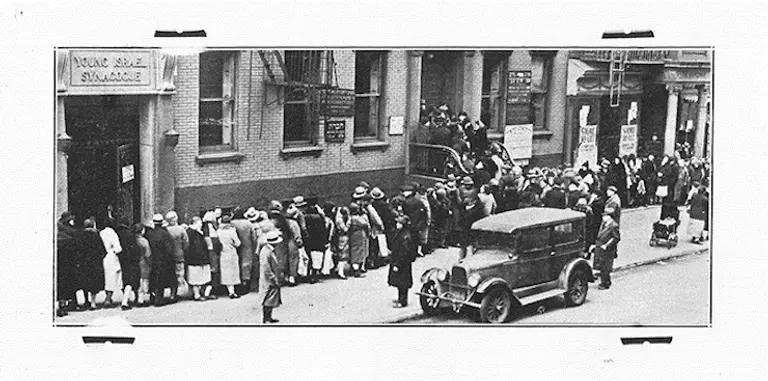

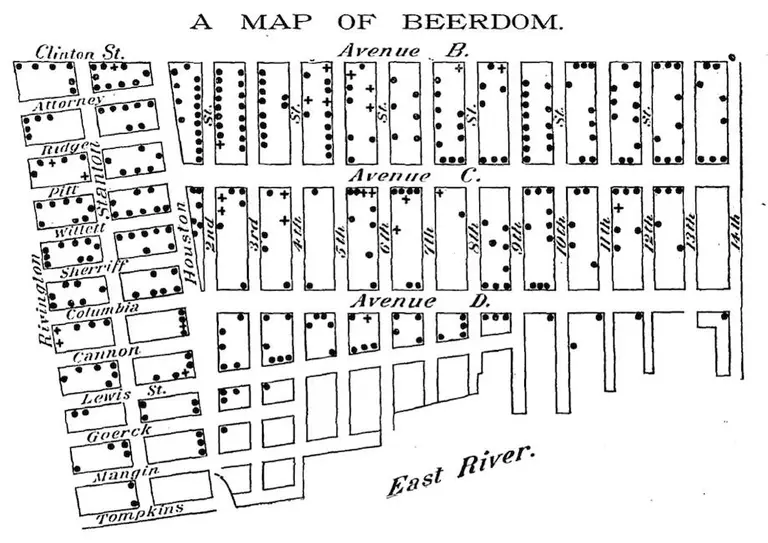

Between 1880 and 1924, 2.5 million mostly-impoverished Ashkenazi Jews came to the US and nearly 75 percent took up residence on the Lower East Side. According to the Library of Congress, by 1900, more than 700 people per acre were settling in a neighborhood lined with tenements and factories. And as quickly as they descended on the streets, all sharing a common language (mostly Yiddish) and most certainly, similar backgrounds, they quickly established synagogues as early as 1865 (the landmarked Bialystoker Synagogue, whose congregants were mostly Polish immigrants from Bailystok), small shops, pushcarts teeming with goods, social clubs and even financial-aid societies.

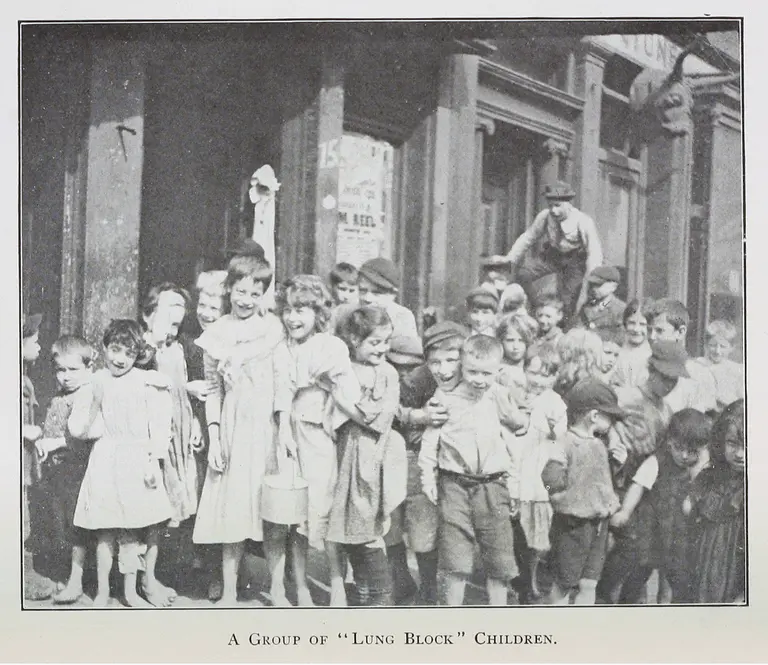

By 1910, the Lower East Side’s population was well over the five million mark, but sadly, such congestion habitually caused havoc.

Nearly half of the city’s deaths by fire took place on the Lower East Side. For many years, tenants lived without indoor plumbing, central heat or central light – but whatever the dangers, diseases or lack of “amenities” they lacked (which was likely the same in the villages they emigrated from), it was still was a world away from the virulent anti-Semitism they faced on a daily basis back home.

According to a 1927 Department of Public Markets report, the first pushcarts were set up on Hester Street in 1866 and by 1900, 2,500 open-air vendors were actively hawking their wares. A suitable way for an immigrant to earn a living and perhaps a stepping stone to a more stable future, these peddlers rose at dawn and headed to nearby stables and paid a quarter to rent one for entire day by elbowing one another for a piece of sidewalk space. But as more and more brick-and-mortar shop owners complained, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia proposed that an indoor market house the street merchants under one roof. Thus, on January 10, 1940, the Essex Street Market opened with 475 stalls. Ironically, within a year’s time, Orchard Street shopkeepers reported a 60 percent decrease in business and blamed it on the relocation of pushcart vendors to the market. Still successfully operation to this day, the Essex Street Market is now a fusion of Lower East Side noshes and egg creams–and stalls selling pricey artisanal cheeses breads, produce, and prime meats.

Well into the 1960s and 1970s, Orchard Street remained notable for discount shopping. Buyers came from far and wide to shop along the neighborhood streets, particularly on Sundays because back then, all uptown stores, including Bloomingdale’s, Macy’s, Saks Fifth Avenue and Lord & Taylor, were not open for business. Retailers like the now demolished Fine & Klein at 119 Orchard Street thrived well into the 21st century by selling top-of-the-line leather goods at discounted prices. Harris Levy at 98 Forsyth Street has been selling some of the finest linens in town since 1894 and Economy Candy at 118 Rivington Street has been in business since 1937.

Schapiro’s © Ted Barron; Other images via Wiki Commons

Schapiro’s © Ted Barron; Other images via Wiki Commons

But some of the Lower East Side’s most popular establishments are sadly gone forever. For instance, for more than a century, the kosher Schapiro Wine Company reigned supreme at 126 Rivington Street where grapes were crushed in a series of cellars that ran through the entire block until the building was sold in 2000. Ratner’s kosher restaurant kept the doors open from 1910 to 2002, serving carloads of blintzes and latkas while patient patrons lined up behind a velvet rope until a table attended by one of the restaurant’s famously rude waiters became available. Though originally located around the block on Pitt Street, it moved to Delancey Street in 1918. But as luck would have it, a number of original food establishments remain and among the most famous is Russ & Daughters, the Yonah Schimmel Knish Bakery and Katz’s Delicatessen.

When Russ & Daughters opened a century ago, Joel Russ could never have imagined his appetizing store being hailed by the Smithsonian Institute as an important part of New York’s cultural heritage, let alone being listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Originally on Orchard Street just below Houston Street, this beloved market got its start selling salt-cured herring and salmon. By 1920, they moved to its current location on Houston Street between Ludlow and Allen Streets, renaming it the J. Russ National Appetizing Store. With his daughters Hattie, Anna and Ida at his side throughout the years, Joel renamed the shop to Russ & Daughters in 1933. As the years passed with his daughters married and his grandchildren old enough to help out, this Manhattan institution is still a family-run business, selling everything from caviar and chopped liver to borscht, babka and bagels. For foodies seeking instant gratification, they can grab a chair a few blocks away at the rather new Russ & Daughters Café at 127 Orchard Street. Better yet, it was recently announced that a second café will open inside the Jewish Museum on 92nd Street off Fifth Avenue in early 2015.

Yonah Schimmel, a Romanian immigrant, first peddled his knishes via a pushcart around 1890, but as his business flourished, Yonah and his cousin Benny Berger rented a small store on Houston Street and named it the Yonah Schimmel Knish Bakery Street. Though Yonah left the business a few years later, his cousin moved the bakery across the street in 1910, where it remains today. Family-owned since its inception and still using the original recipes, the bakery is operated by Yonah’s great nephew, Alex Wolfman.

Katz’s Delicatessen, Image © Julienne Schaer

Katz’s Delicatessen, Image © Julienne Schaer

In 1888, the Iceland Brothers’ delicatessen opened its doors, but when Willy Katz arrived from Europe in 1903, the name was changed to Iceland & Katz. When Willy’s cousin Benny came on board in 1910, they bought out the Iceland brothers and formed Katz’s Delicatessen. By 1917, the deli moved to its present location at the corner of Ludlow and Houston Streets, with a new partner Harry Tarowsky in tow. An emporium of smoked fish, meat, pickles and herrings, the façade we see today was added in the late 1940s. During World War II, the three sons of the owners were all serving their country, and the family tradition of sending food to their sons became the company slogan “Send A Salami To Your Boy In The Army.”

By the late 1970s, all the original owners had moved on to their final resting places, so Katz’s continued operating by way of younger family members. However, by the middle of the 1980s, with no new generation to pass ownership to, long-time friend and restaurateur Martin Dell, along with son Alan and son-in-law Fred Austin purchased Katz’s in 1988. Alan’s son Jake officially joined the store in late 2009 and is currently in charge of all major operations. World-famous for its sky-high, hand-carved pastrami and corned beef sandwiches, this amazing and always crowded deli is said to sell up to 20,000 pounds of meat a week. And for those of you who didn’t know where that classic scene in the film with Billy Crystal and Meg Ryan was filmed, just look for the small sign above a table inside Katz’s that reads “Where Harry Met Sally… hope you have what she had!”

The interior of Katz’s, Image © Julienne Schaer

The interior of Katz’s, Image © Julienne Schaer

Just a few weeks ago, well-founded rumors began surfacing that Katz’s had sold its air rights. Chatter points to real estate developer Ben Shaoul of the Magnum Real Estate Group as the buyer. No other details have surfaced, so we all have to sit tight and wait for the information to become part of public records. Obviously, this information is no surprise given that the neighborhood fell from its iconic pedestal by way of drugs, gangs and shuttered shops in the late 1980s – and by the early 2000s, gentrification produced upscale restaurants, art galleries, jazzy boutiques, a handful of small hotels (i.e., the Blue Moon, and Thompson LES) along with expensive condominiums and gut-renovated tenement buildings garnering market rate prices. The sale of Katz’s air rights is simply another step toward the completion of the gentrification of the Lower East Side.

Still and all, Jake says the pastrami sandwiches will keep on coming, no matter what happens. “The most important thing is that the future of Katz’s is secure… at the end of the day, no developer can ever come in and knock us down to put in a high rise,” Jake recently posted on The Lo-Down website.

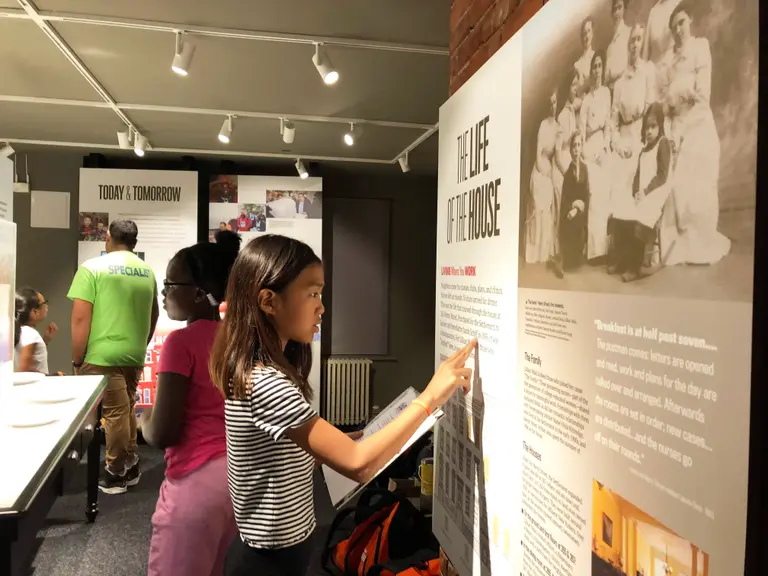

Tenement Museum, Image © Julienne Schaer

Tenement Museum, Image © Julienne Schaer

To learn for yourself what daily life was like a century ago, take a walking tour with the Lower East Side History Project, and then visit the Tenement Museum on Orchard Street. Inside the 1863 tenement apartment house that was home to nearly 7,000 immigrants through the years, the museum has recreated apartments, as they would have looked like from the late 19th century and well beyond America’s Great Depression. Learn about the living synagogues and historic structures in the neighborhood from one of the knowledgeable tour guides at the Lower East Side Jewish Conservancy. Another museum worth a stop is the Museum at Eldridge Street that’s inside a synagogue that opened on September 4, 1887, just in time for the Jewish High Holidays.