Our 220sqft: This couple has made it work for 24 years in a Chelsea Hotel SRO

Twenty-four years ago, when writer Ed Hamilton and his wife Debbie Martin moved into the Chelsea Hotel “everybody at the hotel was in the arts. There were always parties, and somebody was always having a show of some kind.” They’ve spent more than two decades in a 220-square-foot SRO room, and despite not having a kitchen and sharing a bathroom, they have loved every second of it. Where else could you live down the hall from Thomas Wolfe’s one-time home? Or share a bathroom with Dee Dee Ramone?

But eight years ago, the landmarked property was sold to a developer, and since then, it has changed hands several times. Ed and Debbie have lived through nearly a decade of “renovations” (it’s still unclear when and if the property will eventually become luxury condos), all the while watching their rent-stabilized neighbors dwindle as the construction and legal battles got to be too much. In true old-New York fashion, however, Ed and Debbie have no thoughts of giving up their Chelsea Hotel life. They recently showed us around their bohemian apartment, and even as they took us through the building, covered in dust and drop cloths, they speak fondly of their memories and their commitment to staying put. Ahead, get a closer look at why trading off space for history was the right choice for this couple and learn how they’ve made it work, what their wildest stories are from the hotel’s heyday, and what their most recent tenant lawsuit may mean.

Why did you decide to move to the Chelsea Hotel 24 years ago?

Ed: We had long heard tales of the Chelsea Hotel and its famous bohemian residents, from Thomas Wolfe—one of our favorite writers—to the Beats and the Warhol crowd, so it was where we had always dreamed of living when we talked about moving to New York.

Debbie: I got a job in New York in November of 1995 and move here and lived in a Bowery hotel while I looked for a permanent apartment. The Chelsea was one of the first places where I looked, but Stanley Bard told me there were no openings. During my search, I called a number in the Village Voice and was surprised to find that it was for a sublet in the Chelsea!

Ed: I quit my job teaching philosophy and moved here to join her, and after a year in the sublet on the third floor, Stanley Bard, patriarch of the beloved Bard family who ran the hotel for 60 years—gave us our own place on the eighth floor.

You’ve lived here since 1995, so needless to say there have been some pretty significant changes. If you had to narrow it down to one thing, what do you miss the most about those early years?

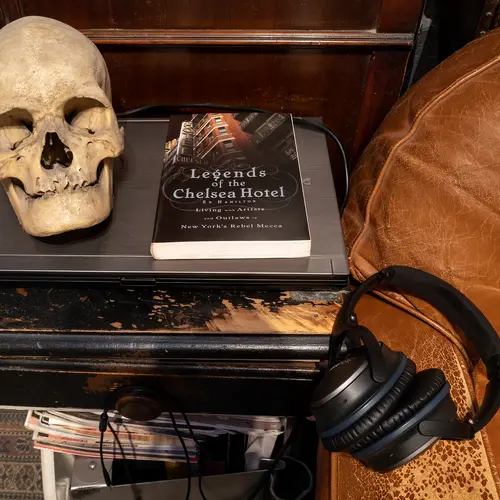

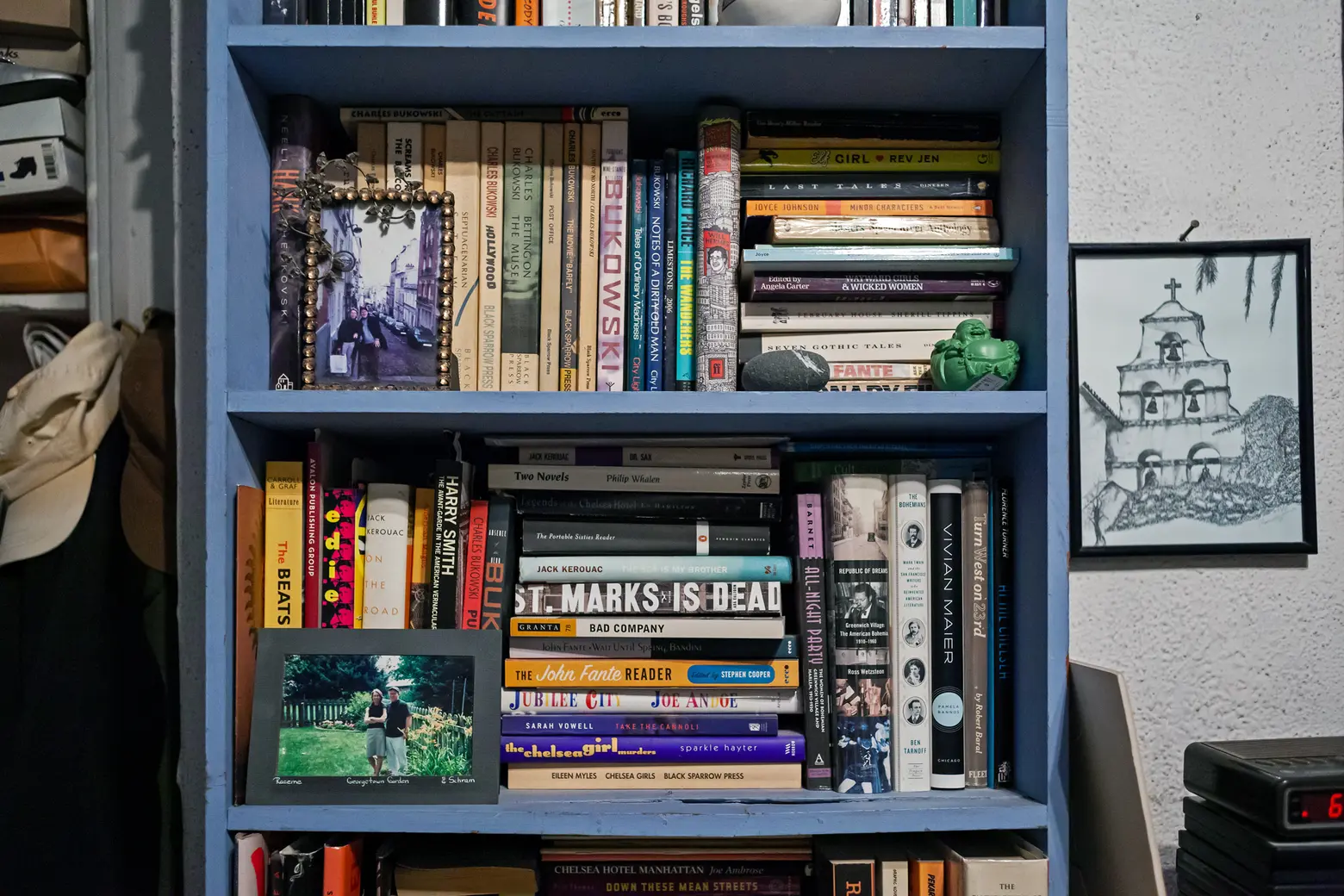

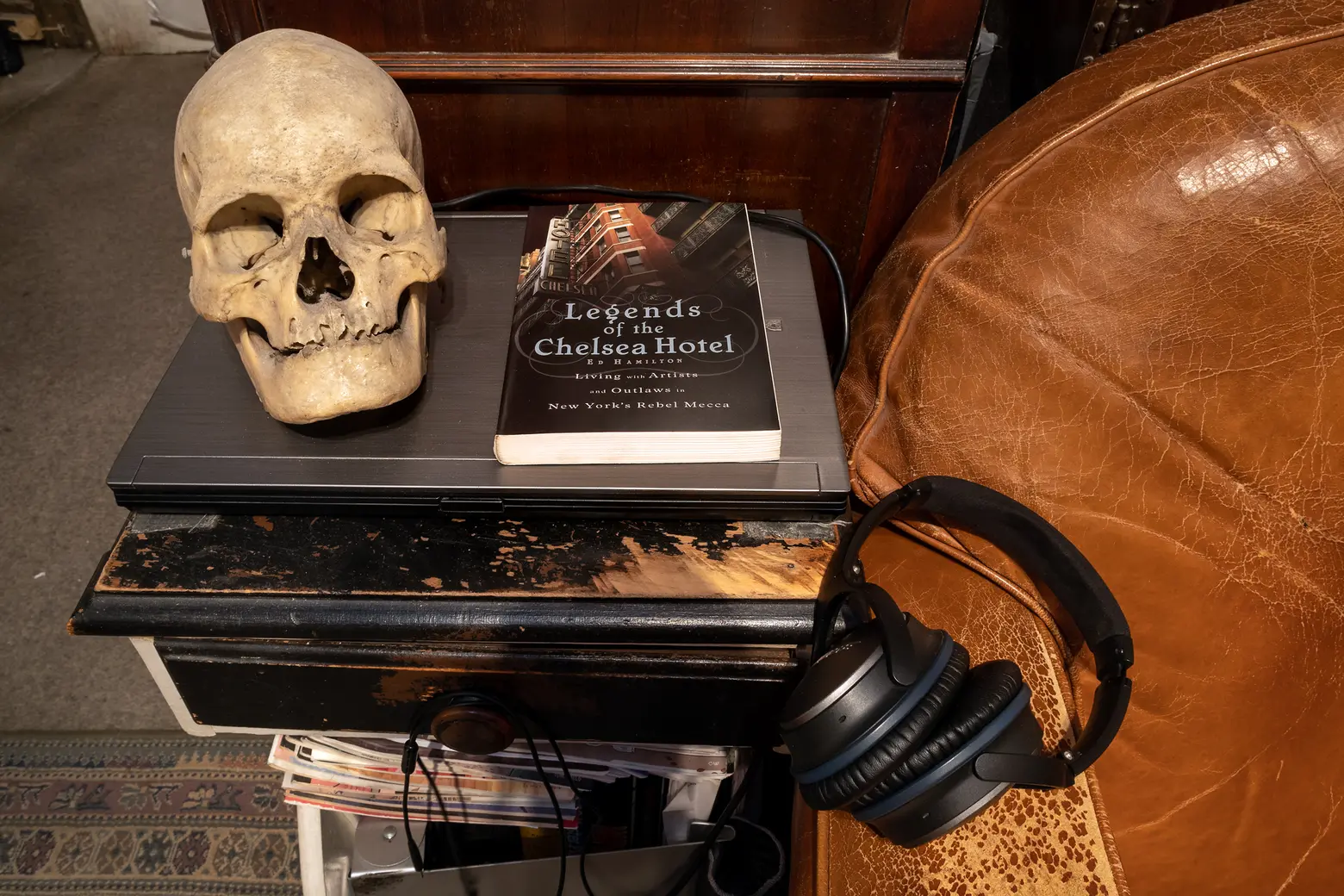

Ed: I miss the creative spirit—which was electric, like a charge running through the hotel that hit you as soon as you stepped into the lobby—and the wide-open sense of possibility that existed in the hotel, and in New York as a whole, at that time. (The worst of gentrification and rampant development was yet to come, which is a theme running through my book, “Legends of the Chelsea Hotel.”) In those days, you might run into anybody in the halls and start up an interesting conversation—or wander off with them into the city. In the space of a week, the room next to us was occupied by a punk rocker, a classical violinist, and an old blues guitarist—and needless to say, we got to hear them practice! Everybody at the hotel was in the arts. There were always parties, and somebody was always having a show of some kind. You could roam the halls and stumble into some sort of a gathering on almost any night of the week.

Debbie: I miss the contagious excitement that tourists from all over the world would bring with them when they checked into the famous Chelsea Hotel. They all wanted to participate in some small way to the Hotel’s tradition. Every once in a while, a tourist would end up here by accident and have no idea what kind of place they had stumbled into. They would ask “is it my imagination or does everybody staying here already know each other?” I also miss having three elevators.

Ed used to play in foosball tournaments and can’t give up his table!

I’m sure it’s hard to choose, but what’s the most outrageous thing you’ve seen or heard during your time living here?

Ed: Well, I guess it’s hard to top the time when Dee Dee Ramone challenged the construction workers to a knife fight, or the time when the cops showed up looking for notorious club kid Michael Alig, who had been hiding out across the hall from us in a drug dealer’s apartment after killing fellow club kid Angel Melendez.

But, for sheer outrageousness, nothing prepared me for the bizarre, cavalier demolition of the rooms once occupied by such figures as Arthur Miller, Thomas Wolfe, Harry Smith, Dylan Thomas, and Bob Dylan, rooms virtually unchanged since they had lived there. (In a bit of poetic justice, however, a homeless man, evicted from the Chelsea, rescued the doors of dozens of these celebrities from the dumpster and sold them at auction for hundreds of thousands of dollars!)

In the apartments that have been gutted, the original wooden shutters like these seen above have been ripped out.

Has it ever been difficult living in a small space together?

Ed: Sure, we’d like more space, but we’re living in the Chelsea Hotel! Too bad we didn’t get a bigger apartment here when we had the chance, but this is a lot better than living anywhere else. The developers who run the hotel simply can’t comprehend this fact; they don’t understand art, or history, or something. To them this place is just a dump, one which they work hard to make more unlivable every day, and they can’t fathom why nobody ever wants to leave.

What about not having a kitchen?

Ed: Sure, I’d like to cook sometimes, but there’s plenty of takeout nearby. Like the space issue, it’s a trade off. (I should emphasize that plenty of tenants here have kitchens and bathrooms and ample space, and in fact several have huge, fabulous apartments. Not all tenants are in SRO rooms like we are.)

Debbie: Not having a kitchen means a decreased chance of no roaches and no mice.

Now that Ed and Debbie have a “private” bathroom, they’ve remodeled the vestibule into a seating area.

Now that Ed and Debbie have a “private” bathroom, they’ve remodeled the vestibule into a seating area.

Did it take some getting used to having to share a bathroom?

Ed: We had lived in group houses before, so we were used to sharing a bathroom. In general, it’s no big deal. When we were in our sublet on the third floor we never had any problems. When we moved to the eighth floor, however, we did run into some problems, as I detail in Legends. Basically, the bathroom had once belonged to the infamous Herbert Huncke, the beat writer and Times Square hustler who introduced William Burroughs to heroin. The remaining junkies of the area were accustomed to using this bathroom as a shooting gallery, and so we were in a turf war with them. Also, at one point we shared the bathroom with three prostitutes. Prostitutes own a lot of underwear, and they liked to wash it in the sink and hang it to dry on every available surface in the bathroom.

Debbie: Since we are SRO tenants the hotel is required to clean and stock our bathroom. Although, these days we frequently have to complain to management to receive our services. Another advantage of hotel living.

Tell us a bit about how you’ve acquired your furnishings and decor?

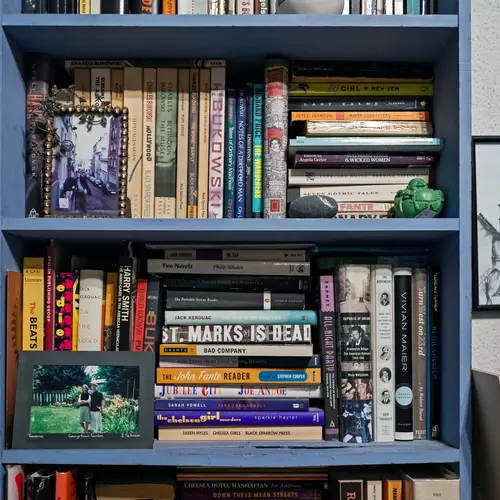

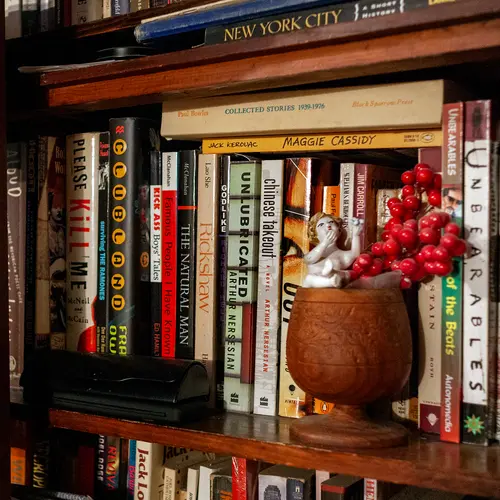

Ed: We’ve never bought any kind of furniture, and most of it is just old, mismatched hotel furniture (lots of styles to choose from in the 135-year history of the hotel!) or things I’ve dragged in from the street. A lot of the art shares the same provenance. Some of the artists are friends from the hotel, however. The two big blue paintings are by Hiroya, a Japanese artist who lived across the hall from us until the year before he died in 2003. Legends, which is dedicated to his memory, tells his story in detail. Basically, he was as much a showman as he was a painter—you either loved him or hated him—but he left the Chelsea to go into rehab around 2002. When he came back, he expected to get his old room back, but it wasn’t available, so he checked into the nearby Gershwin Hotel where he later died.

The black-and-white dog drawing is by David Remfry, a British artist who with his partner and then wife Caroline Hansberry, lived on the top floor of the Chelsea for a couple of decades. David is most famous for his paintings of dancers, including several of Stanley Bard cutting the rug with his wife. The small drawing of a sugar refinery is by Michele Zalopany, who has lived in the Chelsea since the ’80s. That’s Jim Giorgiou’s dog, Teddy, obstructing the factory. The metal “Universal Milkers” sign is from my Grandfather’s milking barn in Casey County, Kentucky. The blue and gold painting above the sink is of Stormé Delarverié, the drag king and emcee of the Jewel Box Review, a famous drag show of the ’50s and ’60s. Stormé, who is also famous as the person who threw the first punch at Stonewall (though there is some dispute over this, as it was, after all, a riot), lived in the hotel from the ’70s up until a few years before her death in 2010. The scorpion was left by a woman who lived here in the ’90s and filled her room with taxidermied animals.

Debbie: Almost everything on our walls was a gift from a friend or something Ed found in the trash. One of the prints is by American artist Robert Williams, who we coincidentally met at the restaurant Florent one night. We also have a piece by Paul Ricard who used to advertise all over Chelsea for fictious shows at the Gagosian. We are giving him honorary status as a Chelsea Hotel resident.

You started writing a blog about the Chelsea Hotel in 2005. What prompted you to do so?

Ed: We started “Living with Legends: Hotel Chelsea Blog” in 2005. We wanted to capture all the weird, outrageous things that went on around this unique hotel before it was swept away in the onrushing tide of gentrification—as even then we could see it coming—and also we wanted to give the artists of this hotel a venue to advertise their shows and present their work. It was Debbie’s idea, and at first I didn’t want to do it, because I was working on a novel. But I finally agreed to write a story about the hotel every week for a year, and I never did get back to the novel. The blog took over our lives for several years. At first it was more of an arts and culture blog (much more fun, let me tell you), but then, once the developers ousted the Bard family, it became more of an organ of protest in the struggle against the gentrification of the hotel and the eviction of our fellow residents.

At first, you published it anonymously. How was your identity revealed?

Ed: Although there was lots of speculation as to who the culprits could be, it took people about eight months to figure it out. In the end it was a woman from outside the hotel who connected the dots because I made the mistake of writing about an event that took place in the elevator while she was aboard (so I was the only other person who saw the action besides her). Even after she unmasked us as the bloggers, most people couldn’t believe it, since we are, for the most part, so quiet and unassuming.

Why did you stop writing?

Ed: It was a lot of work, especially when we started documenting the struggle to Bring Back the Bards (as our slogan ran), and I wanted to do something different for awhile. Also, though most tenants appreciated our efforts, many, including some who wanted to profit from the hotel’s troubles, thought they could do a better job managing the resistance. In the end, we decided it was only fair to let them have a shot at it—with the results you now see. It’s a shame because, in retrospect, we feel we were very close to having the Bards (who were working toward this goal from their side as well) reinstalled in a management role.

You turned this into a book, “Legends of the Chelsea Hotel,” which was published in 2007. How did your neighbors respond?

Ed: Legends was one of the early “blog-to-book” deals, back when that was still a thing, although the stories in it are, in most cases, greatly expanded versions of the ones that actually appeared on the blog, and probably about half of the material didn’t appear at all. I kept the book an absolute secret until it was about 95% written and I had a book contract in hand. It was only discovered when a photo crew showed up unannounced to take pictures of the hotel for the cover and were summarily thrown out. (They were later allowed back in, though only after I received a stern lecture from Stanley Bard, who warned me not to say anything bad about the hotel.)

Residents were, for the most part, supportive of the final result. Inevitably, some had bones to pick with the book: the more upstanding citizens were mad at me because they said I depicted the place as being overrun with junkies and crazies, whose culture, they said, I celebrated; while the junkies were mad at me for disparaging junkies. (“Junkies are people too” is an actual quote from a man who still won’t speak to me. And I agree with him; I just didn’t want them shooting up in my bathroom.)

More recently, you wrote a short story collection titled “The Chintz Age: Stories of Love and Loss for a new New York.” You previously told us that each piece offers a different take on New York’s “hyper-gentrification.” What prompted you to explore this topic?

Ed: After we stopped writing the blog, I worked on a number of other stories about the Chelsea Hotel, much longer pieces, true stories for the most part, with the aim of eventually putting them together into a sequel to Legends. But somehow I wasn’t satisfied with the results I was getting. I think I was too close to the action, and the issues and events involved were too emotionally fraught. I needed to take a step back from the disaster that was still happening (and is ongoing to this day) in the hotel, and the way I did it was by placing the stories outside the hotel, and by fictionalizing.

Since the whole city is undergoing gentrification and hyper-development, I was still able to deal with these pressing issues, while showing how different areas of the city, each beautiful and vibrant in their own way, were being compromised and destroyed. As for the fictionalization: one of the most heartbreaking aspects of this ongoing crisis is the human dimension. Artists, by nature sensitive souls, are forced to try to create while almost literally under siege. At the Chelsea, they reacted in various ways to this onslaught of development, and while sometimes it brought out the best in them, it more often seemed to bring out the worst. By using the techniques of fiction, I’m able to get inside the heads of these bohemian characters and try to understand their actions, and, I think, most importantly, offer them some sort of redemption—which, in a very real way, constitutes my own redemption. So, in a way, “The Chintz Age: Tales of Love and Loss for a New New York,” constitutes a sequel after all.

Ed and Debbie fear that the developers will destroy the hotel’s iconic wrought-iron staircase. Ed finds the artwork in the hallways on the street; the hotel lobby used to be an art gallery for locals, so this is how he’s keeping that tradition alive.

Ed and Debbie fear that the developers will destroy the hotel’s iconic wrought-iron staircase. Ed finds the artwork in the hallways on the street; the hotel lobby used to be an art gallery for locals, so this is how he’s keeping that tradition alive.

Speaking of which, it’s been eight years since construction began at the Chelsea Hotel, and visibly little progress has been made.

Ed: Even after all these years, and I must reiterate, construction has been going on for eight years, it’s still very hard to speak of the ongoing destruction of the Chelsea Hotel. They will build a structure, like a wall or some heating ducts, and then just rip it down and start over again. Just when you think it can’t get worse, it does. Lately, it’s become less a “renovation” than a “desecration,” as every single feature of the historic old hotel, anything with any charm, is being hunted down and eradicated. Most recently, they’ve been demolishing the front room of El Quijote, which we had previously hoped they would spare. And they demolished our SRO bathroom, which doesn’t make a hell of a lot of sense, since they have to provide us one somewhere as long as we remain SRO tenants. But the most egregious act of desecration—and one that I still can’t believe—is that they have blocked our gorgeous original skylight with a hideous elevator landing, depriving the building of the natural light it had enjoyed for 135 years. I now fully expect them to rip out or cover up the historic bronze staircase—though of course they promise not to.

Here, you can see an original hand-carved door (right) and the new “replica” (left).

Here, you can see an original hand-carved door (right) and the new “replica” (left).

How have the relationships among neighbors changed since people starting moving out?

Ed: Some tenants have given in and bought the party line. For the rest of us, it’s pretty much every man for himself, although, surprisingly, the longer this goes on, the more some of us are able to find common ground to oppose the ongoing harassment.

This is the construction mess Ed and Debbie have to walk through to enter their apartment.

This is the construction mess Ed and Debbie have to walk through to enter their apartment.

Just last week, you and three of the other 50 remaining tenants filed a lawsuit against the building owner, Department of Buildings, and the NY State Liquor Authority. Can you give us the background on the suit?

The press coverage of the lawsuit caught us by surprise. We were sorry to see that some of the press mischaracterized the number of tenants living in the building. There are certainly more than five tenants left, but I guess we’re not surprised that journalists would make that mistake; when you walk by the Hotel on 23rd Street it looks nearly abandoned.

In general terms, what is happening at the Chelsea Hotel is happening throughout the city. There are laws in place (though they need strengthening) that were designed to protect tenants, but enforcement is lax. Developers routinely omit or put false information on DOB applications to obtain permits. Our lawsuit asks simply that the Chelsea Hotel, as well as DOB and the SLA, follow these laws that were put in place to protect vulnerable tenants.

The hallways are mostly boarded up; the developers added these doorways outside the staircases.

The hallways are mostly boarded up; the developers added these doorways outside the staircases.

Given the changes that have already taken place, what is your best-case scenario?

Ed: They are planning five bars, so for awhile the Chelsea will probably be party central, annoying everyone in the neighborhood with fights in the streets and drunks passed out in their own vomit on the sidewalk. If the place ever actually opens again as a hotel, the management will see that the people they want to stay here—rich businessmen, bridge-and-tunnelers, the European party set, or whoever—will quickly grow bored with the place. They (whoever is running it by then) will then probably try to capitalize on the hotel’s bohemian history, transforming it into an artistic theme hotel by putting fake Warhols up in the lobby and pictures of Jimi Hendrix in the rooms. But then they will see that the same people as always will continue to want to stay here: that is, people who come to New York looking for an alternative to the suburban malaise, people who genuinely revere the old heroes of Bohemia and want to emulate them. The management will have to reduce rates and start looking for somebody like Stanley Bard to manage the place again.

A photo by James and Karla Murray in 2000, showing the Chelsea Hotel before it sold and its iconic restaurant El Quijote, which recently shuttered.

A photo by James and Karla Murray in 2000, showing the Chelsea Hotel before it sold and its iconic restaurant El Quijote, which recently shuttered.

What are some other spots around NYC that you were saddened to see close recently?

Ed: I don’t know. The place is like a suburban shopping mall now. All I see everywhere are chain stores. I still lament the loss of Donuts Sandwiches which was on the corner of 23rd and 8th. It had a double horseshoe counter with stools; two donuts and a small coffee for $1; cheeseburger deluxe (lettuce, tomato, fries) for $2.95. And you could pay with a subway token if that was all you had. It closed back in the ’90s.

Debbie: It’s more difficult to find a favorite hang out these days because stores and restaurants are opening and closing more quickly than previously. Even though I had not been to Tortilla Flats in ages, I was sorry to hear that they were closing. I get nervous every time I walk by La Bonbonniere in the West Village, but so far, they are still there.

RELATED:

- INTERVIEW: Author Ed Hamilton on how the Chelsea Hotel inspired personal stories of gentrification

- Interview: Ansonia Insider Michel Madie Shares Stories of the Iconic NYC Building

- My 150sqft: Architect-turned-actor Anthony Triolo shows us his custom-designed tiny apartment

All photos taken by James and Karla Murray exclusively for 6sqft. Photos are not to be reproduced without written permission from 6sqft.