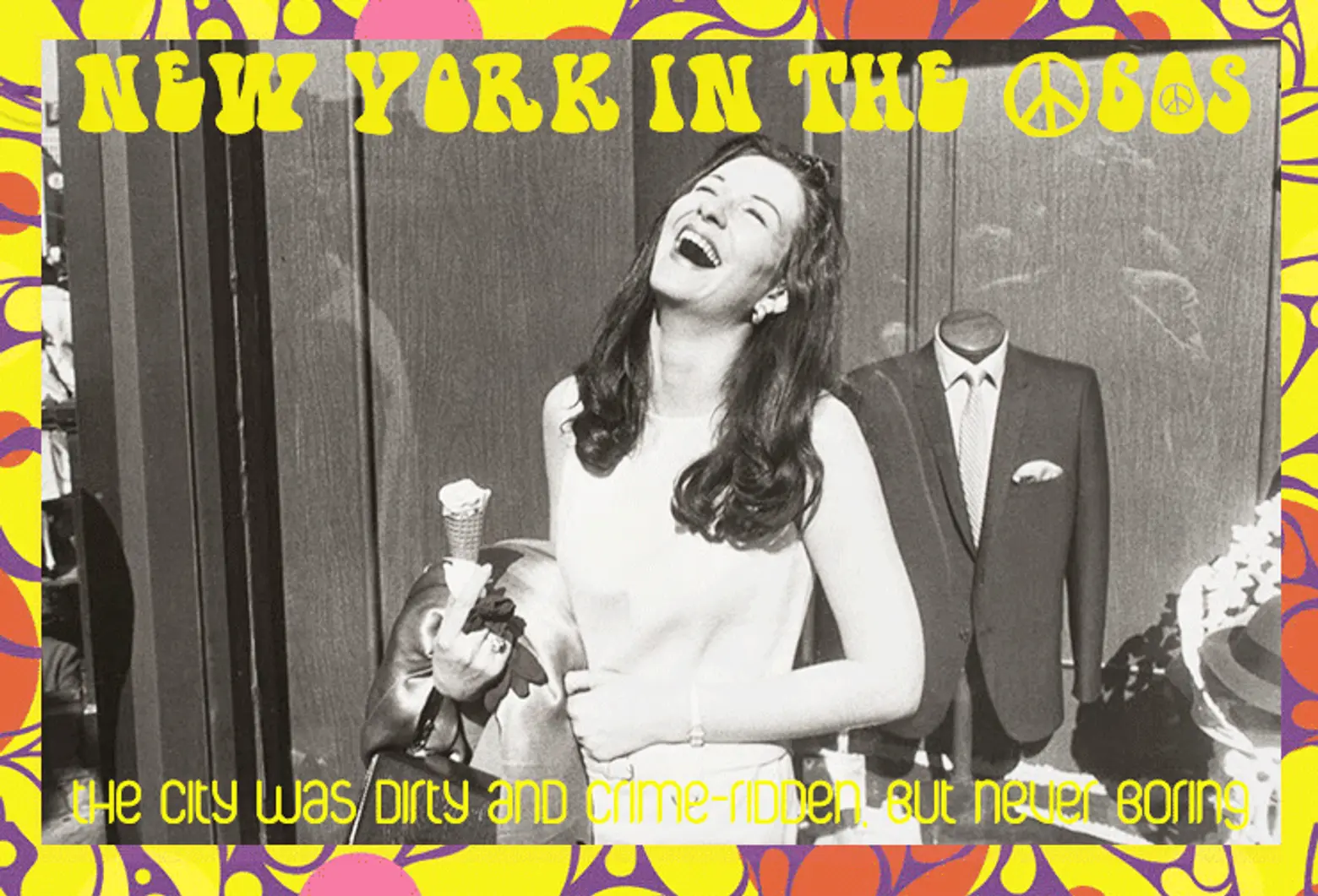

New York in the ’60s: The City Was Dirty and Crime-Ridden, but It Was Never Boring

Photo by Garry Winogrand via Worcester Art Museum

“New York in the ’60s” is a memoir series by a longtime New Yorker who moved to the city after college in 1960. From $90/month apartments to working in the real “Mad Men” world, each installment explores the city through the eyes of a spunky, driven female.

In the first two pieces we saw how different and similar house hunting was 50 years ago and visited her first apartment on the Upper East Side. Then, we learned about her career at an advertising magazine and accompanied her to Fire Island in the summer. Our character next decided to make the big move downtown, but it wasn’t quite what she expected. She then took us through how the media world reacted to JFK’s assassination, as well as the rise and fall of the tobacco industry, the changing face of print media, and how women were treated in the workplace. She also brought us from the March on Washington to her encounter with a now-famous political tragedy that happened right in the Village–the explosion at the Weather Underground house. Now, in the last installment of the series, the girl takes a look at just why New York in the ’60s was such a special place to her.

Mindlessly walking along the street in New York in the ’60s, you might feel a gust of wind and then a handful of grit in your face. Or you would find, strolling along, that the smell of dog poop was following you. Stopping to look around, more often than not you’d find the poop on your shoe. You had unknowingly stepped in it a few yards back and tracked it all the way. Sometimes you would step in some gum, and you’d realize it when your shoe would stick a little at every step.

One time the girl went to visit her parents and her father picked her up at the airport. Settled in the car and pulling out of the parking lot, her father said to her, “I can’t understand why you live in New York. It’s so dirty.” She replied, “I can’t understand why you live in Milwaukee. It’s so boring.”

New York was dirty, yes, and crime-ridden, but it was not boring. It was filled with people who were doing things they hoped would matter, who were committed to their work, their ideals, their city. Sometimes this led to a sense of self-importance, but the usual quota of failures would take care of that in time. The truth is that everybody cared about something.

Architects cared about the buildings they were creating and others that were being torn down. Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore Owings and Merrill designed Chase Manhattan Bank in 1961; Roche Dinkaloo the Ford Foundation in 1963-68 and the UN Plaza from 1969-75; Marcel Breuer finished the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1966; and Eero Saarinen designed the landmark TWA Terminal, which opened in 1962.

At the same time, McKim Mead & White’s Pennsylvania Station was demolished in 1963, and the Brokaw mansions in 1965. Both of those actions inspired the Landmarks Law, which was passed and signed by Mayor Robert F. Wagner, Jr. in 1965, then completing three terms of office. He was followed by John Vliet Lindsey from 1966 to 1973.

Lindsay presided over some of the most difficult years New York has had and sticks in the popular memory most for having declared New York Fun City. For the happenings in the parks, the bike path on the Brooklyn Bridge, the creation of the Mayor’s Office of Film, Theater and Broadcasting, the appellation seemed appropriate. But at the times when garbage mounded five and six feet high during Sanitation workers’ strikes and whenever the crime rate spiked, it was greeted with hoots of derision.

Image via wackystuff/Flickr

Image via wackystuff/Flickr

For the girl it was an exciting time. Some friends were up-and-coming actors, and she went to their Broadway performances. She dated drama critics and went to openings with them. She knew struggling artists—philanthropists, said one, because they contributed their art to society with little or no compensation. She hung out with by-line journalists at the bar behind the Herald-Tribune offices and at the Red Lion in the Village. She worked with a man who was a self-made millionaire before he was 30. She double-dated with a future literary luminary, whose girlfriend told him not to talk shop for fear the girl would steal his ideas.

What the girlfriend didn’t realize was that instead of sneaking others’ ideas, a real spirit of helpfulness prevailed among writers. If you needed some information quickly, you could—and the girl did—call up someone you didn’t know at another magazine, someone who routinely covered the subject. You would explain who you were and what you needed to know and why and ask enough questions to fill the blanks in your knowledge. Others would call you from time to time for the same reason. It was as though there was a pool of favors that everybody could tap into any time one was needed. No one was out to steal ideas. There were enough to go around.

This is how helpful writers and editors could be: One day the girl was in Washington D.C. interviewing the bureau chief of Look magazine—that alone was a big favor. Then a young man interrupted the session wanting to know how to break into journalism. “Do you type?” the bureau chief asked him. In those days, boys didn’t learn to type, only girls did. Boys found the prospect faintly insulting. “No,” he replied. “Well, you have to learn, because no compositor is going to set type from hand-written manuscripts,” said the bureau chief. The young man looked shocked to hear it, but he probably signed up for typing lessons the minute he got home.

If the ups were fabulous, the downs were at least dramatic. More than once, the girl outwitted sexual predators to run home at night with her heart pounding. One time she got stinko on vodka at a party with Russians and slammed her legs in a car door on the way home. Another time she got goosed by a best-selling author. She also had devastating romantic setbacks. Doesn’t everyone?

One would like to say that there is an arc of continual improvement—in living conditions worldwide, in kindness and generosity, and in weather forecasting. But the weatherman still gets it wrong sometimes and it’s way too easy to think of examples of cruelty and brutality. Still, the air is cleaner now and people do clean up after their dogs, mostly.

+++

Read the full New York in the ’60s series HERE >>

Get Insider Updates with Our Newsletter!

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

From watching the old “That Girl” series, I’m guessing the reason a struggling actress could afford that apartment without either a roommate or sugar daddy was because the neighborhood (West 70’s) at that time was so crappy, landlords charged next to nothing to get people to rent an apartment there.