New Yorker Spotlight: Gabrielle Shubert Reflects on Her Ride at the New York Transit Museum

On the corner of Boerum Place and Schermerhorn Street in Downtown Brooklyn is what looks like a regular subway entrance. But upon further inspection, it becomes clear that there’s no uptown and downtown platforms here. This is the New York Transit Museum, the largest museum dedicated to urban public transportation in the country. It’s fittingly located inside a decommissioned–but still working–subway station. And over the last 40 years, it has told one of New York’s most important stories–how mass transit and city development are intricately connected and how public transportation is one of the city’s crowning achievements, in spite of its delays and crowded rides.

Gabrielle Shubert has served as the museum’s director for the past 24 years. She transformed a young institution into a go-to destination for learning about and engaging with urban history. From vintage cars to subway fares, Gabrielle has offered visitors a chance to go behind the scenes and marvel at the wonders of New York City’s incredible public transportation system.

On the eve of her retirement, we sat down with Gabrielle in one of the museum’s vintage cars and found out about her early days as director, the range of exhibits and programming she has overseen, and the institution’s bright future.

New York Transit Museum via Black Paw Photo

What drew you to the Transit Museum 24 years ago?

I worked at the MTA’s public art program. At that time it was called Arts for Transit, but it’s now MTA Art and Design. I was looking to expand the depth of the work I was doing, and there weren’t that many opportunities since Arts for Transit was such a small department. I was looking around the agency, and there was an opening here at the museum that I was lucky enough to get.

It was a difficult time for the museum then. What decisions did you make to reinvigorate it?

The museum had just received a good investment from the MTA. Mass transit, as you know, has ups and downs and cycles. It had benefitted from some investment in the time it was good, and it was now on one of those downward slides. As a cost-cutting measure, the New York City Transit President suggested that the museum be closed. The staff who was here at the time—I wasn’t here when that happened—mobilized all their friends and supporters to come to the public portion of an MTA board meeting to speak about how important the museum is. The MTA board said, “We won’t close the museum, but it has to become self-supporting.” And that was when I came in. It was my job to figure out how to reinvent this place as a self-sustaining institution. There were a lot of avenues that we looked at to make that happen. The first was that we knew we needed to establish a not-for-profit status, a 501(c)(3), so we could raise money. It took us while to do that.

This was the early ’90s, not the best of economic times, and a lot of museums were cutting back on hours and programming. We didn’t. We expanded. Rather than being open one weekend day per week, we were open the entire weekend. We tried to boost our retail operations because that was a good money maker for us. The MTA, though they had decided not to give us cash funding, was quite generous with their in-kind support. One of the things that really helped us get on our feet was when the MTA offered us a space at Grand Central to open a store for six months. I knew it was going to be longer than that. We had it for three years, which was fabulous because we were on the main concourse. That was a real boost to us in terms of our revenue stream.

We also boosted our membership program and started renting our facility more regularly for film shoots and parties. We started fundraising, but that takes time in New York. We started having an annual fundraising dinner right here in this building. The first two years we actually put cute little cafe tables in all of the cars. But after two years, we had outgrown this space. I think we earned about $200,000 from our first gala, which happened after I was on the job for six weeks. Our gala last year grossed a million dollars. Even though we are about to have our 40th anniversary, we are a relatively young institution. For example, when you compare us to the Museum of the City of New York, which has over 100 years of fundraising tradition, we’re new.

Via Black Paw Photo

Via Black Paw Photo

You have a very diverse audience. Are children a big part of that?

We have one of the most diverse museum audiences. Everyone uses mass transit across every economic level. I think that’s one of the great things about us. Using mass transit is one of the great common denominators. I want to be presenting programming that is relevant to a really diverse audience.

Every year, we see over 20,000 school children and another 5,000 camp groups. We’ve started a fabulous program for individuals with special needs. In particular, we do a special after school program for children on the autism spectrum who are often really interested in trains. We engage them in things have to do with trains, and while we’re doing that, we’re teaching them social skills and they don’t even know it. By the end of the program, they’ve made friends and are setting up play dates. It’s a beautiful thing when you see these kids at the end of a program and when you hear back from the parents, “Can we come back? Can we do this program again?”

Via Black Paw Photo

This is a very unique museum. How does it successfully tell New York’s transportation story?

Well, not only do we tell its transportation story, but we tell its infrastructure story too, which I think it what makes us unique as an institution. We are really the only museum in New York, aside from the Skyscraper Museum, that is looking at the city from the perspective of its infrastructure. And the underground and aboveground infrastructure of the MTA subway, buses, rail, commuter rail, bridges, tunnels is a really big and interesting story.

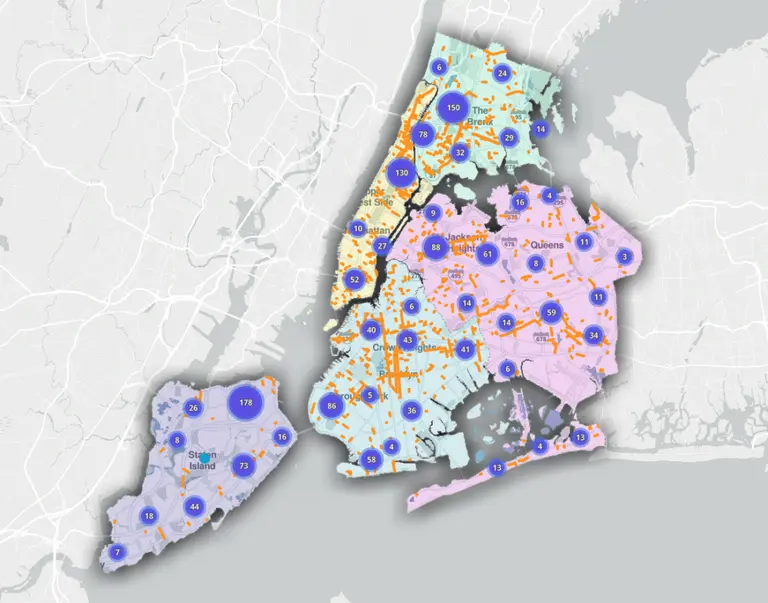

This is a story about cities and how they develop. We look at how mass transit was the catalyst for the growth and development of New York City. I’ll use the example of Queens, which was farmland until the number 7 line extended out into Queens and real estate developers started saying, “Ah, there is a subway coming. These are going to be great commuter neighborhoods. We’re going to build here. We’re going to make money.” That was the impetus behind the growth of the city. When mass transit was going to come, real estate developers jumped on that opportunity to build and develop the city.

I think part of our mission is to reveal how complicated it is to run the subway system and two commuter rails in New York. Everybody loves to hate the subway and their train commute into the city. These systems run 24/7, sometimes with a time distance between trains of less than three minutes, on a signal system that is over 100 year old. It’s part of our job to reveal that to people.

ElectriCity via Black Paw Photo

How does the permanent collection exist in relationship to special exhibits?

What makes us really special as an institution is our collection of vintage vehicles, which are subway and elevated cars that ran in New York from about 1900 to the present. You could call that the “permanent collection,” but there is some rotation within that. For instance, in our current exhibit “ElectriCity: Powering New York’s Rails” we have a car on loan to us from the Shore Line Trolley Museum up in Connecticut. It’s the oldest electric rail car that ran in the Northeast.

Another example is from a show we did on how money is collected throughout the subway system called “Show Me the Money: From the Turnstile to the Bank.” We actually had the money collection car on display here. We’re about to do an exhibition called “Bringing Back the City,” which is about how the MTA’s various operating agencies respond to crises when they happen in the city, and we’ll have a pump car on display. It will show how during floods, serious storms, and incidents, the subways are pumped out.

The permanent turnstile exhibit, via New York Transit Museum

You have worked on wide range of exhibits. Do you have a favorite?

I loved “Show Me the Money.” Nobody really thinks about what happens when you swipe your Metrocard except for what the balance is. And when it was tokens and dealing with cash, you were buying a 10 pack or two at a time, whatever you could afford. How did that money get processed? It got picked up by a car that went through the stations at night. Depending on your age, you may remember seeing those yellow cars with bars on the windows. They would go through the stations at night, and armed agents would get out of the car with bags and go to the booth and empty out the safe and then go back and process it. That money went to a building on J Street where all three subway lines converged. There were little rails in the tunnels that went to the building on which the money was transported. When that money room went out of service and a new processing center opened, we were clear to tell that story.

Tell us a bit about the upcoming exhibit “Bringing Back the City: Mass Transit Responds to Crisis.”

We have a big staff, and they’ve been immersed in this topic for many years, so a lot of it has to do with talking among ourselves. It also has to do with objects that come into our collection or realizing that there’s a big chunk of the collection that has an interesting story to tell. The “Bringing Back the City” exhibition that we’re doing in September came to me right after Hurricane Sandy. I was contemplating how huge the impact of the storm was going to be on all our systems. We reopened the museum two days after Sandy hit and were hearing stories of what our colleagues within the agency were doing to clean up after the storm and get service running again. They were working four to five days at a stretch without getting home, dealing with components that had been corroded by salt water and tunnels that were filled to the roof with water. That made me think about what our people had done after 9/11.

After their shifts were finished, transit employees were driving our equipment to Ground Zero in order to assist in rescue and recovery. They were bringing the backhoes, front loaders, and the crane cars and generator cars to the pile to try and find survivors. Somehow the transit people were forgotten, and I wanted to tell that heroic story.

We’re focusing the exhibit on 9/11, the blackout of 2003, the snowstorm in 2010, Hurricane Irene in 2011, and Hurricane Sandy in 2013. I think that mass transit spells normality for a lot of people, so when you can get around again and get to work and go buy groceries, that’s when life feels normal again. For me, mass transit became a symbol of how the city heals itself and gets back to normal after a devastating crisis.

BRT Car 1273, Via Black Paw Photo

BRT Car 1273, Via Black Paw Photo

The nostalgia trains have become incredibility popular. How does the museum decide when and where to commission these vintage trains?

We do them in the summer mostly because that’s when it’s fun to go on a trip. We try to pick destinations that are really fun, like the beach. We’ve gone to the Rockaways, Coney Island, Orchard Beach, and Van Cortland Park. And then we’ve started doing one in the fall to Woodlawn Cemetery to get a Halloween theme in there. Sometimes we try to connect it to programming and art exhibitions when it makes sense, or sometimes it depends on which cars are in good shape and ready to go out on the road.

IND R-4 ‘City Car’ Number 484 via 6sqft

Is there anything in the museum that you wish would be recommissioned for use by the MTA?

This IND R-4 ‘City Car’ Number 484 (from the 1930s). Isn’t it beautiful? The bight turquoise walls, the striped rattan seats, these bulbous, incandescent light fixtures, the fans, the ceramic pole handhold. This is such a beautiful car, and with the lighting quality, riding to work would feel like you’re in your living room. You could just be reading along with the windows open.

Even though you’re retiring in September, you’ve had a hand in planning for the future. What forthcoming projects and exhibits is the museum working on?

We are going to redo the website and work on a new branding identity that will help us better market who we are. And we’re really anxious to do some serious work on making our collection more accessible to the public; that will probably mean a really extensive digitization project.

We’re also working on a really interesting international project with an organization called the International Association of Transport Museums (IATM) that will look at advances in transportation and communications technologies after World War I. We’re about to hit the anniversary of the end of the war in 2018, so we’ll be looking at different cities around the world and how those advances grew and developed. There will be a web component so that even though we’re telling the story from a New York perspective here, people can go online and see it through the eyes of the UK, Germany, Portugal and Sweden.

Gabrielle on a vintage train, via 6sqft

What imprint do you hope you’ve left on the museum?

What’s been important to me as director of this institution has been to present cohesive and synchronized content to the public—our collections lead to relevant exhibitions, which in turn lead to interesting programming that digs even deeper. I also think that creating a family within an institution is really important. There’s something to be said for consistent leadership. Having been here for a long time, I think that has helped the institution stay on a course and hopefully contributed to its success.

In summing up 24 years, what has sharing the history of New York City and its incredible transportation system meant to you?

I’ve always been interested in how cities work. Being able to reveal some of those mysteries to people is really fun. I have one of the coolest jobs there is because I get to see how the subway really works. And if I can impart how cool the subway system is to people, it’s hugely satisfying to me. That’s the way I have tried to approach our programming. What don’t people know about this incredible system that keeps our city functioning?

+++

New York Transit Museum

Corner of Boerum Place and Schermerhorn Street, Brooklyn Heights

The Transit Museum has an upcoming Nostalgia Ride on Saturday, August 8th at 11:00 a.m. to the Bronx’s Orchard Beach on a WWI-era IRT subway car. For more information, click here.

[This interview has been edited]

RELATED:

- NYC’s First Subway Line Moved Passengers Just One Block–Can You Guess Which?

- Photo Series Captures Three Years of NYC Subway Cars Being Dumped in the Atlantic Ocean

- The NYC Subway Still Runs on 1930s Technology, Pen and Paper

- New Yorker Spotlight: Curator Sarah Forbes on the Museum of Sex (It’s Not Exactly What You Think It Is)

Get Insider Updates with Our Newsletter!

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

When I was a kid my classmates and I would ride the Third Avenue El to Mount Saint Michael High School. We loved riding in an old car with windows that opened, wicker seats and screw in light bulbs. I seem to remember the light bulbs made a loud POP when they hit the street around Webster Avenue. That was entertaining for us but probably not much fun for unsuspecting pedestrians below.

Of course it was the older kids who were wild enough to pull that stunt. I always thought a transit cop from an adjoining car would arrest them at any moment.