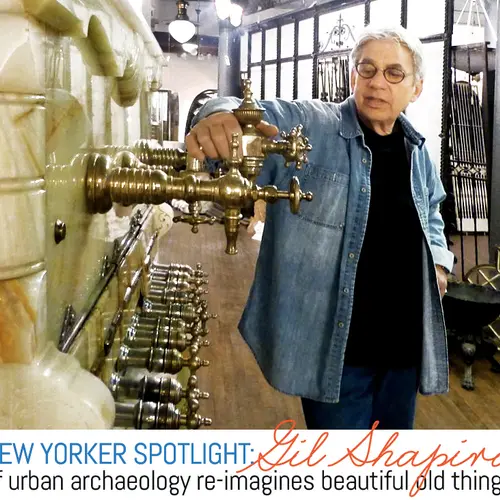

New Yorker Spotlight: Gil Shapiro of Urban Archaeology Re-Imagines Beautiful Old Things

Native New Yorker Gil Shapiro founded Urban Archaeology in the early 1970s, when the salvaging movement was just catching on. With a collector’s–and creator’s–eye and an entrepreneurial spirit, he began re-imagining architectural remnants as treasured additions to the home environment. This month the company has been preparing for an auction taking place on March 27th and 28th, handled by Guernsey’s auction house, when nearly 1,000 of their long-treasured pieces of history will be sold to prepare for a move to a new location.

First opened in Soho in 1978, the store’s early customers–including Andy Warhol and other denizens of what was undisputedly the epicenter of the art world–adored the unique and time-treasured aspects of Shapiro’s restored architectural salvage pieces, yet they would always find ways they wished they could customize their favorite items. Finding that he excelled at bringing a fresh perspective to pieces of historical and architectural importance, he started reproducing individual pieces as well as creating new lines of bath fixtures and lighting, many of which originated in places like the Plaza Hotel, New York’s Yale Club and the St. Regis Hotel.

This mermaid and mer-man were sculpted as central characters for the Place de la Concorde fountain in Paris, replaced by replicas after a renovation. Auction estimate: between $125,000 and $150,000 each.

This mermaid and mer-man were sculpted as central characters for the Place de la Concorde fountain in Paris, replaced by replicas after a renovation. Auction estimate: between $125,000 and $150,000 each.

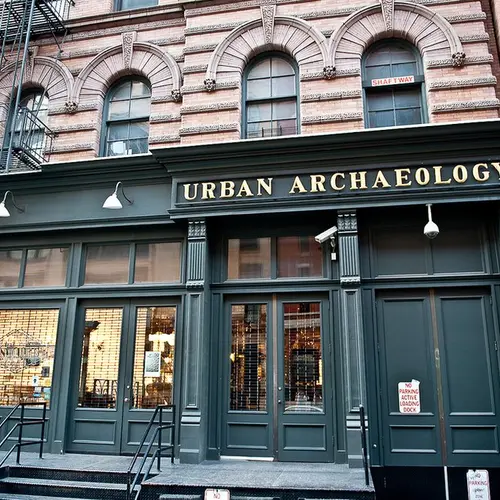

Shapiro’s wife and longtime collaborator, NYC interior designer Judith Stockman, officially joined the business in 1997 as creative director. The company moved to a six-story building in Tribeca where it now employs a team of craftsmen specializing in all aspects of manufacturing–in addition to being a leading design resource for new lighting, bath and kitchen furnishings with complementary lines of American artisan tile and mosaics, Urban Archaeology is one of the only manufacturing companies left in downtown Manhattan.

The company, which has about 62 employees, currently has two Manhattan stores as well as locations in Bridgehampton, Boston and Chicago, with distributors all over the country. Later this year, they’re moving to a new location in Chelsea, and a new factory in Long Island City is in the works.

The pair of towering Art Deco doors on the cover of this auction catalog was salvaged from a Harlem nightclub.

The pair of towering Art Deco doors on the cover of this auction catalog was salvaged from a Harlem nightclub.

From the Union Depot train station in Troy, NY, this glazed terra cotta clock, from the early 1900s, is expected to fetch between $60,000 and $80,000 at auction. Photo courtesy of Urban Archaeology.

From the Union Depot train station in Troy, NY, this glazed terra cotta clock, from the early 1900s, is expected to fetch between $60,000 and $80,000 at auction. Photo courtesy of Urban Archaeology.

This ten-foot-in-diameter antique brass chandelier was salvaged from a prominent Manhattan bank. It is very, very big.

This ten-foot-in-diameter antique brass chandelier was salvaged from a prominent Manhattan bank. It is very, very big.

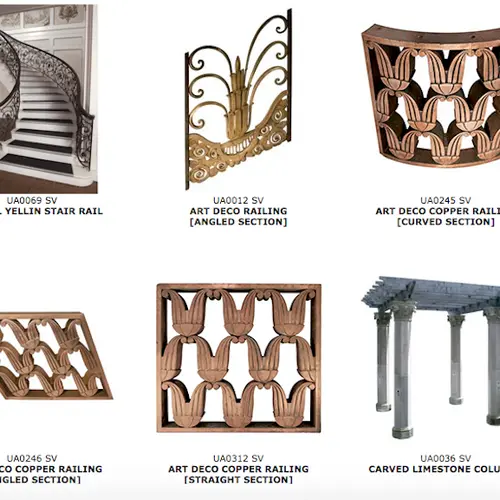

Just a few of the pedigreed wares inside the classic big-shouldered, cast-iron-framed Tribeca space include gates from St. Patrick’s Cathedral, an Art Deco pendant light that once hung in the Chrysler Building and an awe-inspiring pair of 14-foot doors that marked the entry to a Harlem nightclub in the ‘70s–all of which will be up for auction this weekend.

On the subject of this weekend’s auction, Shapiro explains, “It’s been three months of doing this, 18 hours a day or longer; getting everything brought here, getting everything photographed, getting everything estimated, getting it all online, getting all the measurements right–which they aren’t.” To the suggestion that he seemed pretty calm for all that, he replies cheerfully, “Well, it’s too late. This is it.”

He also found time to address our curiosity about why the company’s work is so unique, the early days in 1970s Soho, and what the future holds.

What made you decide to make reproductions and new pieces instead of just dealing in antiques and salvage?

Gil: Because our manufacturing was what was carrying us. We grew in that, and as the people I had working for me retired, they were replaced by people that did lighting. You turn around and there’s no one who has any experience in demolition and that’s what you need to do salvage. So you’re set up for something new.

Even though you mostly create new items, do you still buy old things?

Gil: Not so much. If it’s something really great, we would try to find a home for it, maybe another dealer, someone else in the city, Olde Good Things is an example, they’re a really good company with good people. If it’s something really great, and no one else wants to deal with it and I think it has to be saved, we’ll deal with it…reluctantly.

Do you design new items as well as manufacturing reproductions?

Gil: Yes, we design new ones ourselves; and we change designs because of clients saying, “yes, I want this, I don’t want this, I want three lines here. I want four lines here.” Then we take a lot of the products we make and customize them even more. At Polo Ralph Lauren’s new flagship store at 711 5th Avenue in the old Coca Cola building, for example, we took a light that we make that’s this big (indicating a normal-sized lantern), and had it triple-scaled–maybe four times the size, changed some of the details on it, customized it–it’s an outdoor light so we had to make sure it was up to code. The Coca Cola building has a brass facade and it’s from the ’20s and it has a patina and they wanted the light that we made to look like it was put on at the same time. So that’s what we do.

And then you have to deal with technology: How do our lights look next to something done at the turn of the century, or in 1930, with LED lighting? You have to be able to make sure it looks like an incandescent bulb when it’s lit–and they’re getting better and better at that. They might want them dimmed. They might want an electric eye. And we do that.

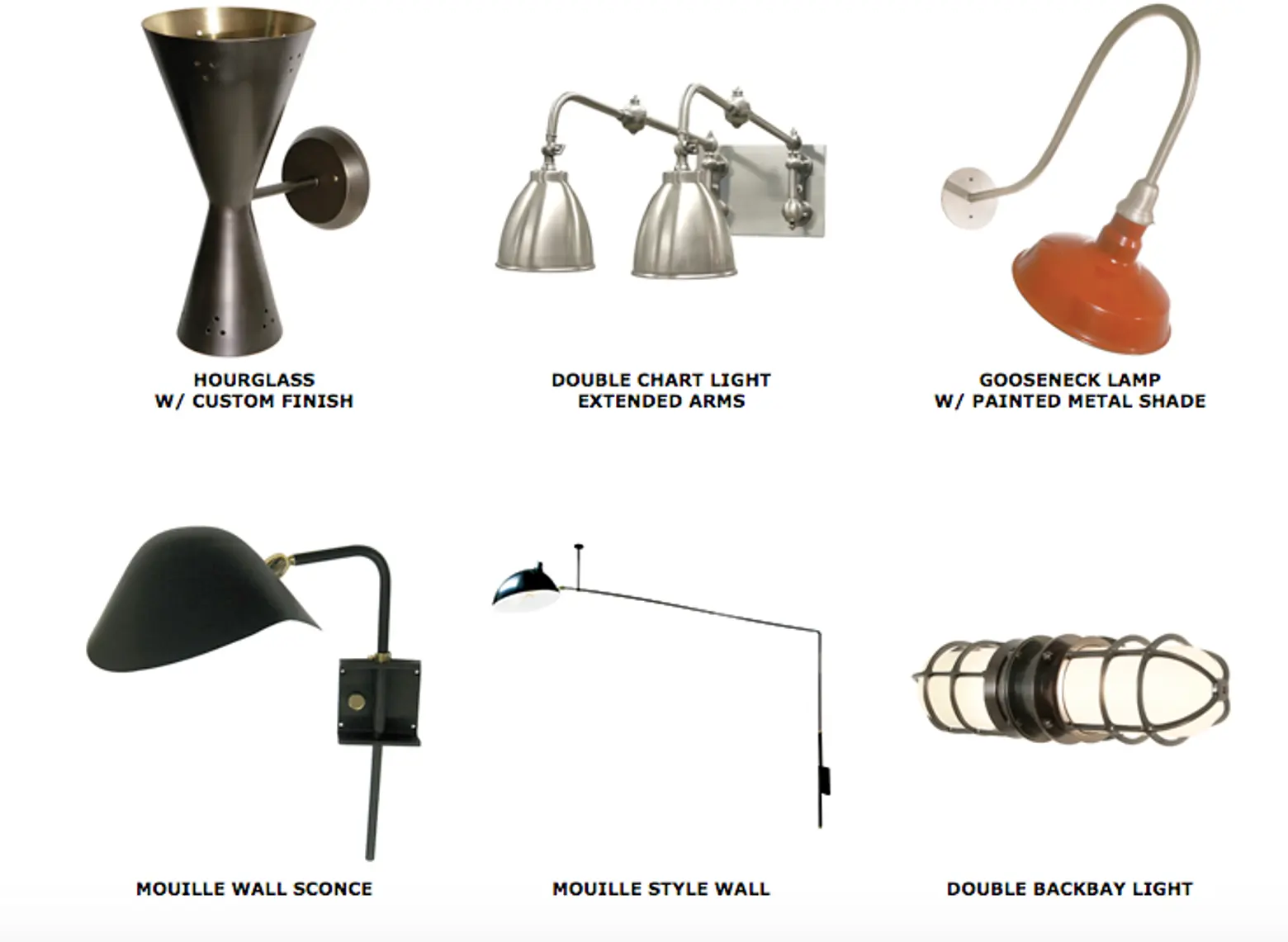

Custom reproductions of mid-century lighting by Urban Archaeology.

Custom reproductions of mid-century lighting by Urban Archaeology.

Regarding the salvage pieces, how did you go about finding them?

Gil: We were very active as a salvage company in the ‘70s and ‘80s, even early ‘90s. We’d look for job sites; we’d get building permit lists; we’d see who was under construction; we’d see who was doing renovation. We would drive around looking for dumpsters–not to dive into but to see where people were working. You’d see what permits were let out. It’s all public knowledge.

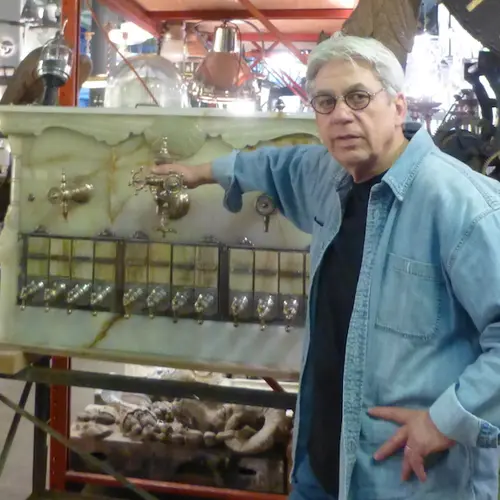

This soda fountain made of white onyx comes from a pharmacy in Fremont, Ohio, circa 1890. Opening bid: $30,000-40,000.

This soda fountain made of white onyx comes from a pharmacy in Fremont, Ohio, circa 1890. Opening bid: $30,000-40,000.

Do you have a favorite piece, something you’ll never forget or maybe still have?

Gil: There’s a soda fountain over there (he points to an amazing white onyx soda fountain that will be up for sale in the weekend’s auction) that’s pretty special. My personal favorite has nothing to do with history or being historic or something people are going to know. But to me, it’s something from the 1880s that was really neat. And you can build it into your house; it doesn’t have to be in a commercial establishment.

One Madison sits to the right of the Met Life tower

One Madison sits to the right of the Met Life tower

What was an example of a really cool decorating project you’ve worked on–or a memorable customer you’ve worked with?

Gil: Something we’ve done recently on 23rd street and Madison Avenue–for the Related building called One Madison. They came to us with a rendering–they needed lights in the bathrooms. It’s a glass building, so you can’t penetrate the shell of the building when you’re getting electricity the way you need it in a bathroom; you have to hang it from the ceiling, and up from the floor. So anybody that wants to shave, put makeup on, or brush their teeth, you need a light on your face; and if you have a pendant hanging down its not optimal.

So–from somebody else’s drawing–we made a hanging mirror with LED lights. And then we had to deal with the fact that because there’s a glass wall behind it you’re going to see what the back of it looks like. So we had to make sure it was finished on every side, top and bottom. Then we had to deal with the fact that it had to be dimmable, it had to provide enough lighting and it had to have a driver that was remote. So it had to go somewhere in the ceiling.

Now this is a whole building of them, not just one; we had to deal with the codes involved with the remote driver and how you access it if something goes wrong: What happens if the LEDs burn out, how easy is it to get to? In other words, you don’t want to do something like building a boat in your basement for sixty years and then you can’t get it out because it’s bigger than your doorway.

And then we had to do it so it was warm looking– we’re getting away from incandescent bulbs and were getting into LEDs and it’s really great saving the planet, it’s really great saving energy. But now you have to make it so that a homeowner could change the light. So if you do it in strips and it burns out, you need somebody that’s an electrician to do it. If you do it in a pad that would just clip in, you can unclip it and put another one in. So we had to think out of the box about what’s going to happen eight months from now, and what’s going to happen ten years from now. Then you say “What else can you think of?”

What you do is you build one, and you have it working; and you use it. And then you say, “Oh, here’s a problem, the mirror gets dirty and it’s a six foot object hanging from the ceiling.” So we had to deal with a brace going back. That’s what makes for good design: it’s form and function, it’s not just form. And those are all of the things that we think of that in most cases a great architect or designer would think of as well, but we have to think beyond that in case they left something out.

When/how did you first get interested in this kind of salvage, and in collecting? Did you really sell your older brother’s furniture set to pay for something you’d won at an auction, as the story goes?

Gil: Growing up in Brooklyn, I was a junior in high school. I was coming back from school and there was a commotion–like someone got robbed–and I was curious. Turns out there was a store that was being auctioned off. It was a drugstore, and drugstores and ice cream parlors were usually combined. If you go back a long time, that’s where the kids go, there were no VCRs, no television, they went to ice cream parlors. You’d have a nickelodeon, you’d have little gaming machines. I’d had my first date in that store.

They were selling off their stock, old inventory and old signs–which I later got into. I’d always had a passion for wood. What those drugstore cabinets look like–every five feet there was a gargoyle affixed to the top of the cabinet; its mouth was open and there would be a chain hanging, holding a leaded glass globe. There are still drugstores that have them—Massey’s Uptown has one, Bigelow’s has one, Kiehls has a lot of those things. So anyway thats what I bought. The bidding went: $10,000, $5,000, $1,000, any bids? So I put my hand up and I said a hundred dollars. And no one else bid. And I said, “Here, I have three dollars.”

So did you really sell your brother’s bedroom furniture to your super?

Gil: (sheepishly) Yeah. And I didn’t have a truck to bring it home, so I had to sell some of my parents’ living room stuff. And then they come home to…a drugstore. They got their stuff back from the super, and threw out a lot of the things I bought, but kept some of the nice things that didn’t take up a lot of room. I still have those leaded glass urns in my house.

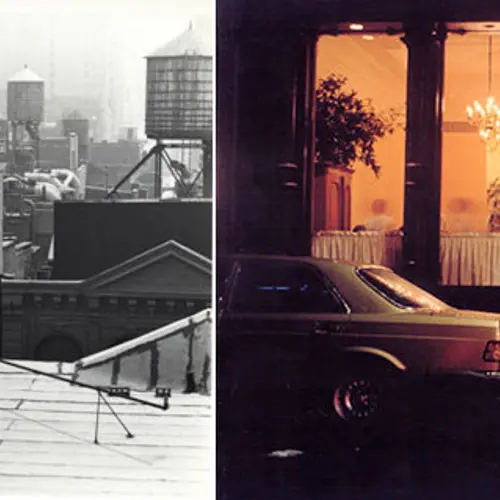

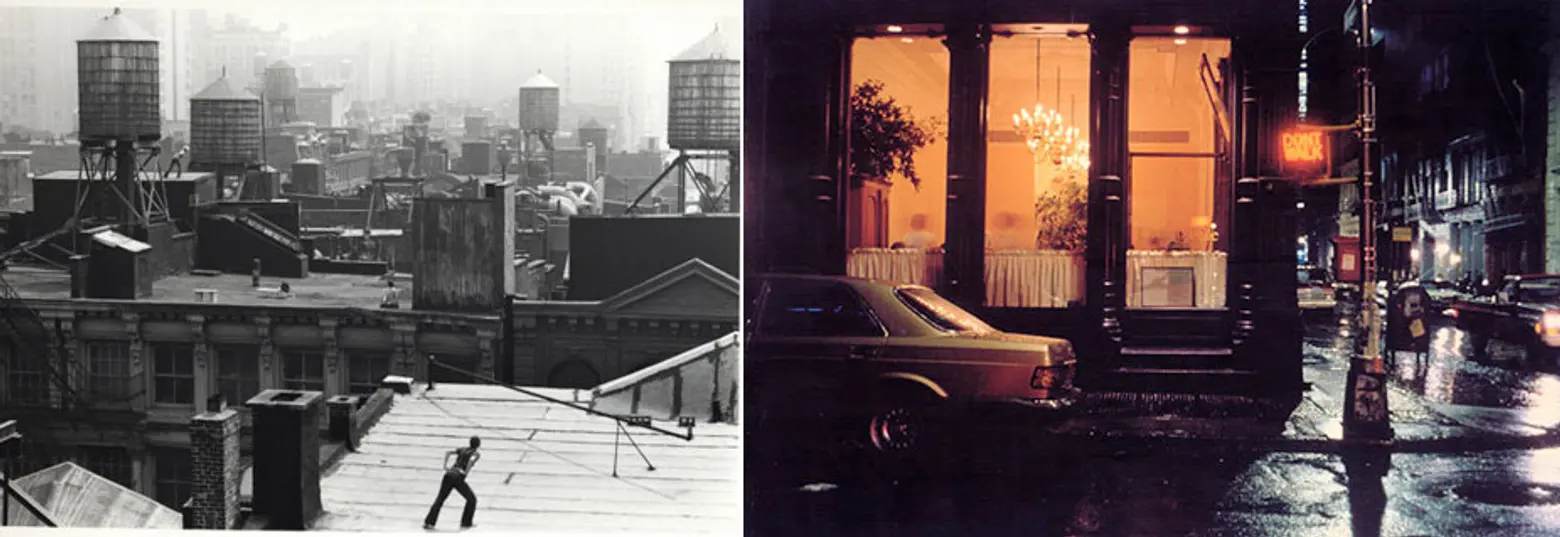

Images: Soho in 1970 via NYPL archives (top) Rooftop above Lafayette in 1970 © Babette Mangolte (L); Grand Street in 1979 (R) via Chanterelle

Images: Soho in 1970 via NYPL archives (top) Rooftop above Lafayette in 1970 © Babette Mangolte (L); Grand Street in 1979 (R) via Chanterelle

You started out in Soho in the 1970s. Can you describe what it was like having a store in Soho in the ‘70s? Who were your fellow merchants?

Gil: Here’s what it was like: It was Dean & DeLuca, and then every art gallery in the world. It was the art center of the world. I had original things from buildings that were 100 years old that were hand-carved, and down the street there’d be five galleries that were selling things that were still wet, that were just made. I was trying to sell hundred year old objects for $250, and there were new things being sold for $3,500 and $5,000. So it was frustrating. I couldn’t sell my stuff. Things didn’t feel like they had value to me if the person that made it was still alive and they could make another one. Also, someone could take a painting and put a little hook on the back and put it on the wall. Ours, you needed a contractor. It weighed 100 pounds or 200 pounds. You had to deal. So it was always a frustration.

For the first five years that we were open, the questions that were asked in our store were like this: They’d look at a bathtub and say, “Do you sell this?” And I’d say something like, “Nah, we just took the lease over and it was here. Would you like it? Because we have to clean it out.”

“Where’s Dean & DeLuca?” was another, so I would always say it’s around the corner. But one day five years later I was actually shopping at Dean & DeLuca and the person on the next line said, “Do you know where Urban Archeology is?”

Giorgio DeLuca was working one of the registers, and I said to him, “Wow, we’ve made, it, Giorgio!”

Then I told the guy, “It’s around the corner.”

It was a lot of great artists, which was really interesting: Basquiat, Andy Warhol–we had Andy Warhol’s checkbook with checks endorsed to us left blank. There was Walter de Maria, Charlie Bell and the Photorealists and the Pop Art movement. It was really fabulous. And I have a really neat art collection–I traded with a lot of artists for our objects.

Soho was really crowded and very commercial. A lot of people on the corners selling socks and belts and stuff like that. And I lived in Tribeca which had nothing. It had Odeon. I’d hang out at Odeon every night and come back with $3,000 in checks. I had polaroids with me, and I’d sell stuff at the bar. Everybody went to the art galleries–we were just a novelty.

How have the neighborhoods changed?

Gil: Soho just became more and more commercial. Stores there are also in Beverly Hills and France and East Hampton and everywhere in the world. In Tribeca, for a lot of reasons, you can live on the ground floor here. It’s not a destination. It’s a neighborhood. It’s really a neighborhood. There are a lot of people that still live here that were the pioneers of the neighborhood. There was so little traffic. I think it’s great. There are some great restaurants down here, and still so little traffic. If we depended on traffic we’d be out of business. We do a lot of our business via email and online.

A wall of options: reproduction lighting in the Tribeca showroom.

A wall of options: reproduction lighting in the Tribeca showroom.

You’ve mentioned that this is the only active manufacturing building left in the neighborhood; we’ve been hearing a lot recently about places like Sunset Park, and how Brooklyn is beginning to see a renaissance of light industry, and how overall there’s this resurgence of things that are locally made. Do you see that happening, and do you feel that you’re part of it?

Gil: I do see that happening and I love it! This is a manufacturing district, but there are very few manufacturers left here. Without getting into politics, we almost lost the automobile industry in this country. We invented the automobile. We invented mass production. We invented the assembly line. The garment district left in the ’60s. There’s now somebody around here selling watches that were made in Detroit. There were no watches being made in America.

So do you think there’s a resurgence?

Gil: Without a doubt. The problem is that we’ve lost a lot of the skills we had, for a lot of reasons. For one, everything became disposable. And there isn’t a lot of talent. We lost that too, but we’ll get it back. We’re a great country with great people. You can bring it back. And it’s cost effective. If you’re going to be making it here instead of trucking it in from St. Louis, or Germany, that offsets some of the costs. We can make everything that we used to make and we can make it better. We don’t have to outsource everything.

If you were just starting out today in NYC with a business like yours, what neighborhood would you choose and what would your strategy be?

Gil: I’m usually pretty good at picking neighborhoods. Probably parts of Brooklyn that are more residential now, that could become more commercial. Parts of the Bronx. I’m thinking of Long Island City for myself: We’re actually opening a factory in Long Island City.

One of the things that makes me decide where to start is with the talented people I have and where they live. And how they could get to where the factories would be. So that’s one of the things that’s going to drive me. I don’t want to lose my people. They have to get there and it has to be affordable to get there. And affordable means they can’t spend two and a half hours getting to work and two and a half hours getting home. That won’t last. Everybody has to have a great quality of life and part of that is travel.

So that’s one of the criteria which is quite interesting. Red Hook, for example is an issue. How do you get to Red Hook? There’s no public transportation, you’re right near the tunnel you have to drive a car. Its a great area but there are issues there.

How have the internet and technology changed your business? How have you seen that evolve, in comparison with the early days?

Gil: It’s great. I used to get phone calls in the early ‘80s when a designer was having a meeting and do we have any of this or that, and we’d take a Polaroid picture and we’d call a messenger–this was even before fax machines were widely used. Now if somebody wants something, there’s a digital camera and you can email it to them.

So you can reach the whole world.

Gil: Totally. We’re doing an auction here and it’s going to be online. Maybe there’ll be ten people showing up. And hopefully there’ll be 20,000 people bidding online.

From everywhere in the world.

Gil: Yeah. It’s kind of neat.

[This interview has been edited.]

+++

Find out more about the auction taking place online and at the Urban Archeology store at 143 Franklin Street in Tribeca on Friday, March 27 and Saturday, March 28, 2015; check out the items in the auction catalog here and here.