New York’s dirty little secret: The apartment kitchen

Model of tenement kitchen via the Tenement Museum

Unlike the warm and welcoming kitchens found in many U.S. cities, in New York, kitchens are more likely to be dark and dank hallways or neglected corners crammed with miniature appliances than actual rooms. In many New York apartments, kitchens don’t even merit their own room but take the form of what is commonly described on listings sites as the “open concept living/kitchen area” (a feature welcomed only by those who don’t use their kitchen or have no qualms about grilling a steak just inches away from their sofa). Worse yet, New York kitchens not only frequently merge with living rooms but also other parts of the home. In many old tenements, bathtubs and showers can be found in the kitchen too.

While many curious features of New York apartments can be solely blamed on limited space, the sad state of the city’s kitchens is a more complicated matter. In fact, it is not that the city’s apartment kitchens have shrunk over time but rather that many apartments never had proper kitchens in the first place. The kitchens were either added on long after the apartment’s construction or were original built to serve multiple purposes (for example, to serve triple duty as a kitchen, bathing area and bedroom). The result is a hodgepodge of kitchen facilities that range from cramped to outrageously dysfunctional. To fully appreciate why it is so difficult to find a New York apartment with the type of kitchen taken for granted in most U.S. cities, however, the city’s architectural, health and culinary histories all need to be taken into account.

If you find cooking exhausting, this studio rental at 232 East 6th Street may be the ideal solution—the bed is conveniently located at the foot of the stove.

If you find cooking exhausting, this studio rental at 232 East 6th Street may be the ideal solution—the bed is conveniently located at the foot of the stove.

The History of Tenement Kitchens

Prior to the turn of the twentieth century when housing inspections became increasingly common, there is limited documentation on New York’s apartment kitchens. What is known for certain is that in most tenements, kitchens had little or no ventilation and generally did not have running water (until 1901, water was generally accessed via a communal pump in shared courtyard). Most kitchens did have had an icebox where one could temporarily store perishable goods, such as milk, and were equipped with a coal and in some cases, gas stove.

With few fire regulations, tenement stoves posed many dangers to residents and were a common source of building fires. In addition, while using a stove in an unventilated tenement apartment was often unbearable in the summer months, in the winter months, the same stove was frequently the tenement’s only source of heat. As a result, on cold nights, a single kitchen often served as a communal bedroom for a dozen or more residents.

“Kitchen interior” [with bathtub], The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1934 – 1938 (L); “Tenement interior; kitchen coal stove, bed” The New York Public Library Digital Collections, 1934-1938 (R)

“Kitchen interior” [with bathtub], The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1934 – 1938 (L); “Tenement interior; kitchen coal stove, bed” The New York Public Library Digital Collections, 1934-1938 (R)

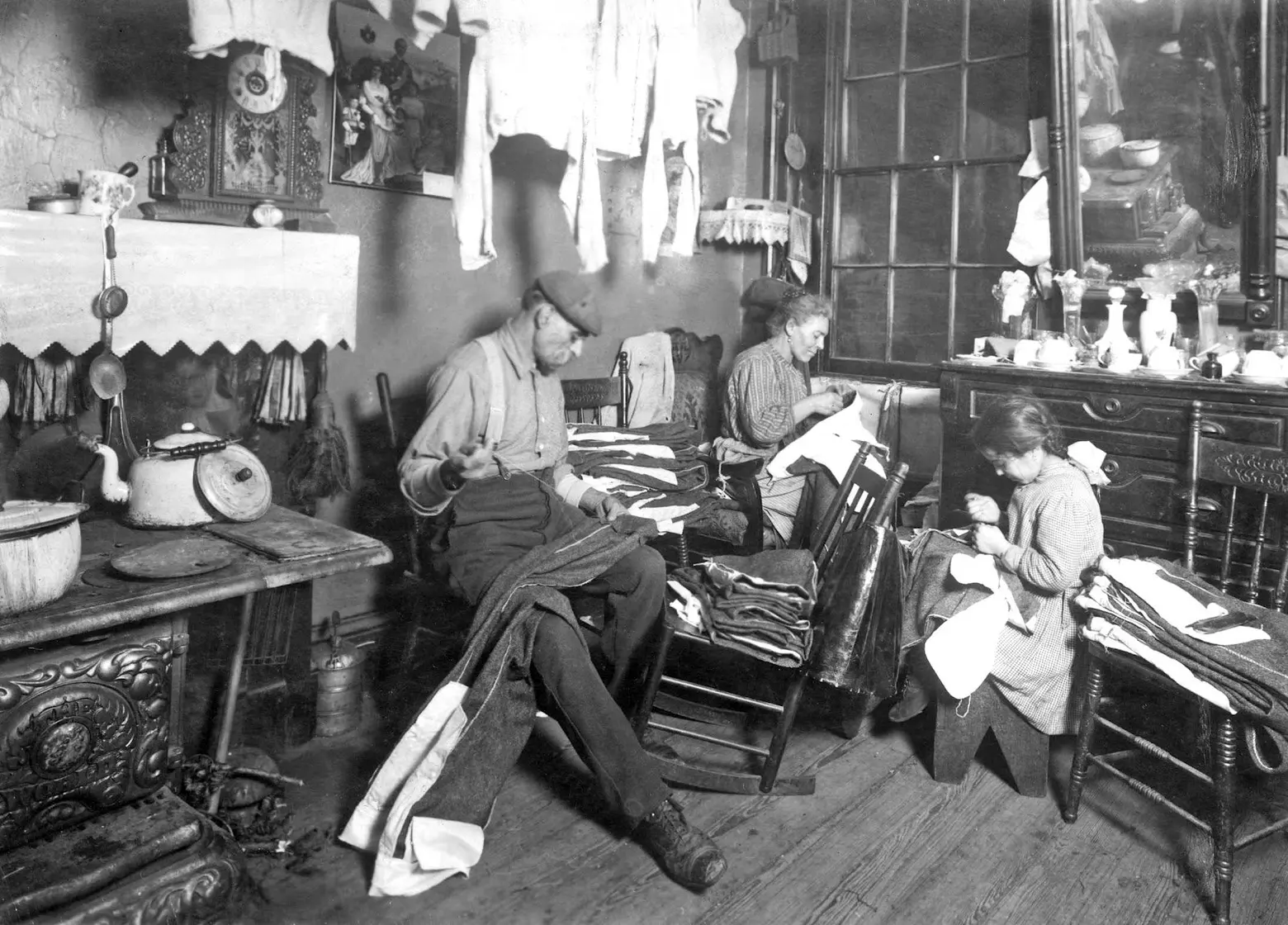

Both the location and size of tenement kitchens varied and most were adapted over time by tenants to serve multiple purposes from bedrooms to bathing rooms to sweatshops. Indeed, well into the twentieth century, the New York garment industry relied on piecemeal work carried out in tenement kitchens, usually by women who were also caring for young children or the elderly and as a result, unable to work outside the home. This meant that many tenement kitchens also doubled as small-scale sewing and canning factories.

Photo by Lewis Hine. The New York Public Library Digital Collections

Photo by Lewis Hine. The New York Public Library Digital Collections

Despite the poor condition of many New York apartment kitchens, the Tenement Act of 1901 resulted in only minor improvements. While the Act did contain language about the need for improve ventilation and attend to fire regulations and required landlords to make water available in each unit, there were few guidelines directly focused on kitchen improvements. Over a century later, regulations for kitchens remain just as vague. By definition, kitchens must be eighty square feet or more (a kitchenette is any kitchen facility that measures less than eighty square feet), the ceiling, walls and floors of any kitchen must be made of fire-retardant materials, and the kitchen must be supplied with gas and/or electricity and with artificial lighting. If the kitchen was built after 1949, it must also contain a window of at least three square feet that looks out on to the street, a court yard or an air shaft. Notably, there are still no guidelines or incentives that encourage landlords to provide proper counter space, storage space or full-size appliances.

This compact kitchen at 232 East 6th Street has limited space to store cooking pots, utensils and dishes but does offer two hooks on the wall for overflow coffee mugs and a small window rack for wine bottle storage.

This compact kitchen at 232 East 6th Street has limited space to store cooking pots, utensils and dishes but does offer two hooks on the wall for overflow coffee mugs and a small window rack for wine bottle storage.

Kitchen-Free New Yorkers

New York fashion photographer Bill Cunningham famously lived without a kitchen until the final years of his life when he was forced to move out of his small room located above Carnegie Hall. Even after Cunningham moved to an apartment with a kitchen, however, he maintained that he had no need to cook at home. Unlike Cunningham, artist Louise Bourgeois once had a kitchen, which she considered necessary while raising children, but soon after she turned her attention to art full time, the kitchen in her Chelsea home was one of the first rooms to be reclaimed in the name of art. Despite occupying an entire townhouse, Bourgeois reportedly threw out her kitchen stove and replaced it with two small gas burners to create more workspace. While Cunningham and Bourgeois’ insistence that one doesn’t need a kitchen at all may strike adults in most cities as odd, in New York, living without a kitchen is by no means rare or peculiar.

Until the 1950s, boarding houses and hotel apartments were the most common form of accommodation for single New Yorkers and in some cases, for childless couples. This meant that a high percentage of people without children didn’t have kitchens and either dined out every night or ate communally in a boarding house dining room. As single New Yorkers started to move out of boarding houses and into their own apartments in higher numbers in the 1960s, apartment kitchens became more commonplace, but in many cases, kitchens remained improvised affairs comprised of a small refrigerator and hot plate rather than full range of kitchen appliances and storage facilities. Even as hundreds of new high rise residential buildings were constructed in the 1960s to 1970s, kitchens often remained secondary features and many looked more like kitchenettes than kitchens regardless of how they were categorized.

Without access to or even a strong desire for proper kitchens, New Yorkers have developed what may be the world’s most extensive market for take-out and take-away food. Today, from Whole Foods to the smallest bodega, one can find a wide range of cold and hot food take-away options reflecting nearly any culinary tradition on the planet. Whatever your taste, you can likely satisfy your craving at any time of day or night—in most cases, without even leaving home. At times, however, city residents have embraced even more impersonal alternatives to cooking.

Automats, automated cafeteria-style diners, were first introduced in the early twentieth century and remained a popular option with New Yorkers for decades. But at the Horn and Hardart, a popular chain of automats in New York, one could do more than acquire a coffee or cheese sandwich or Salisbury steak in the middle of the night. As Patti Smith recalls in Just Kids, she met poet Allen Ginsberg, who eventually became her friend and mentor, at the Horn and Hardart while attempting to purchase a cheese sandwich. Had Smith spent more time in her kitchen, would this fated meeting have ever happened?

“Automat, 977 Eighth Avenue, Manhattan.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1936.

“Automat, 977 Eighth Avenue, Manhattan.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1936.

The Kitchen of the Future

With the Internet of Things (IoT) slowly but surely seeping into our everyday lives, kitchens are soon expected to undergo a radical overhaul for the first time in decades. For example, it is already possible to purchase Samsung’s recently released Family Hub refrigerator. The appliance is equipped with multiple cameras that beam images of your rotting food to your smart phone, At home, the screen on the front door of the refrigerator doubles as a home entertainment system (in a studio apartment, this means your refrigerator can now effectively replace your television and stereo system).

In the near future, however, we will be able to do more than watch our food rot in real time or blast music from our refrigerator. Moving forward, everything in our refrigerator is expected to be equipped with a small sensor. Sour milk will soon be able to send a notification asking to be dumped down the sink while simultaneously alerting our grocery service to add a replacement carton to our next order. In other words, refrigerators will soon be about communication as much as they are about preservation.

In many respects, the kitchen of the future is a made-for-New York solution. In a city where kitchens have long been tolerated more than embraced, the “thinking” kitchen of the future seems likely to find a home in New York, because it has always been and appears destined to remain a city where kitchens are better left out of sight and out of mind.

RELATED:

Get Inspired by NYC.

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

Good historic recall, and for the contemporary NY kittchen, finally someone who dares to say that broiling a steak (not to mention sardines) feet away from your sofa may not be a good idea. Open kitchens are great in a big loft or house, but not in a typical NYC apartment.

About history, miserable kitchens were not limited to tenements. Many semi-luxury or luxury buildings built from about 1930 to the sixties had “Pullman” kitchens, a small sink, two hot plafes and an undercouter fridge, in a corner or closet (look at Tudor City). Or “galley” kitcens usually no more than 60 square feet, which only qualify as kitcenettes, but are rarely marketed as such.

Now, developers have discovered the virtues of “open” or “California” kitchens. The main benefit (to them) is that the open concept gives an illusion of space in increasingly cramped living rooms (look at 600 sq. ft. “one bedrooms” ln new, expensive condos). Although those kitchens are unusable for serious cooking that inevitably is messy and smelly, the epitome of luxury is to equip them with pseudo-professional appliances with a forbidding array of knobs and cast iron, which immediately tell visitors thar serious money was spent. Those kitchens are rarely even close to a window and are often located smack at the entrance of the apartment. Who wants to be welcomed by a display of appliances?

It is interesting how buyers and renters have been brainwashed to believe that an open kitchen is a great asset rather than a manifestation of developer greed. The same applies to the shrinkage of actual floor space as compared to avertised square footage in acity where there is no regulation specifying a standard calculation method. Take a sample of floor plans for old and new apartments offered for sale, and try to calculate the actual floor space square footage: you will find that for older coops, it is usually about 10% less ghan the advertised figure, but that for recent condos, the discrepency can exceed 20%, presumably because condo owners are the proud proprietors of outside walls But that is another story…

History, so much history in NYC. Please keep some of the old things, that is one reason so many visit NYC. Red brick builidngs, old storefronts and so on.