New York’s tradition of uncapping fire hydrants to beat the heat

When temperatures soar, fire hydrants across the city flow freely and not necessarily to put out fires. The practice, commonly known as “uncapping,” has long served as a way for city residents to cool off. Although it is not entirely legal, it is generally tolerated, especially when temperatures climb above 90, and for a number of legitimate reasons.

In New York, finding relief from the heat is by no means an easy or even pleasant experience, and this has much to do with the state of the city’s public pools. They do exist, but the city’s pools remain limited in number, excessively over crowded, and for most kids and even adults, difficult to navigate due to their excessive rules. No water shoes, no phones, no food, no hats in the water, no men’s swimming trunks without a mesh lining, no beach balls, no t-shirts (unless they are white), no newspapers, and no swimming allowed without taking a shower first (and yes, the locker room attendants do watch and will publicly humiliate you if you try to skip this step). So, what sounds like more fun? A dip in a city pool or a spontaneous waterpark on your own street corner? For thousands of young New Yorkers, the choice is obvious, which is why uncapping has long been a preferred choice of relief from the heat.

The history of uncapping

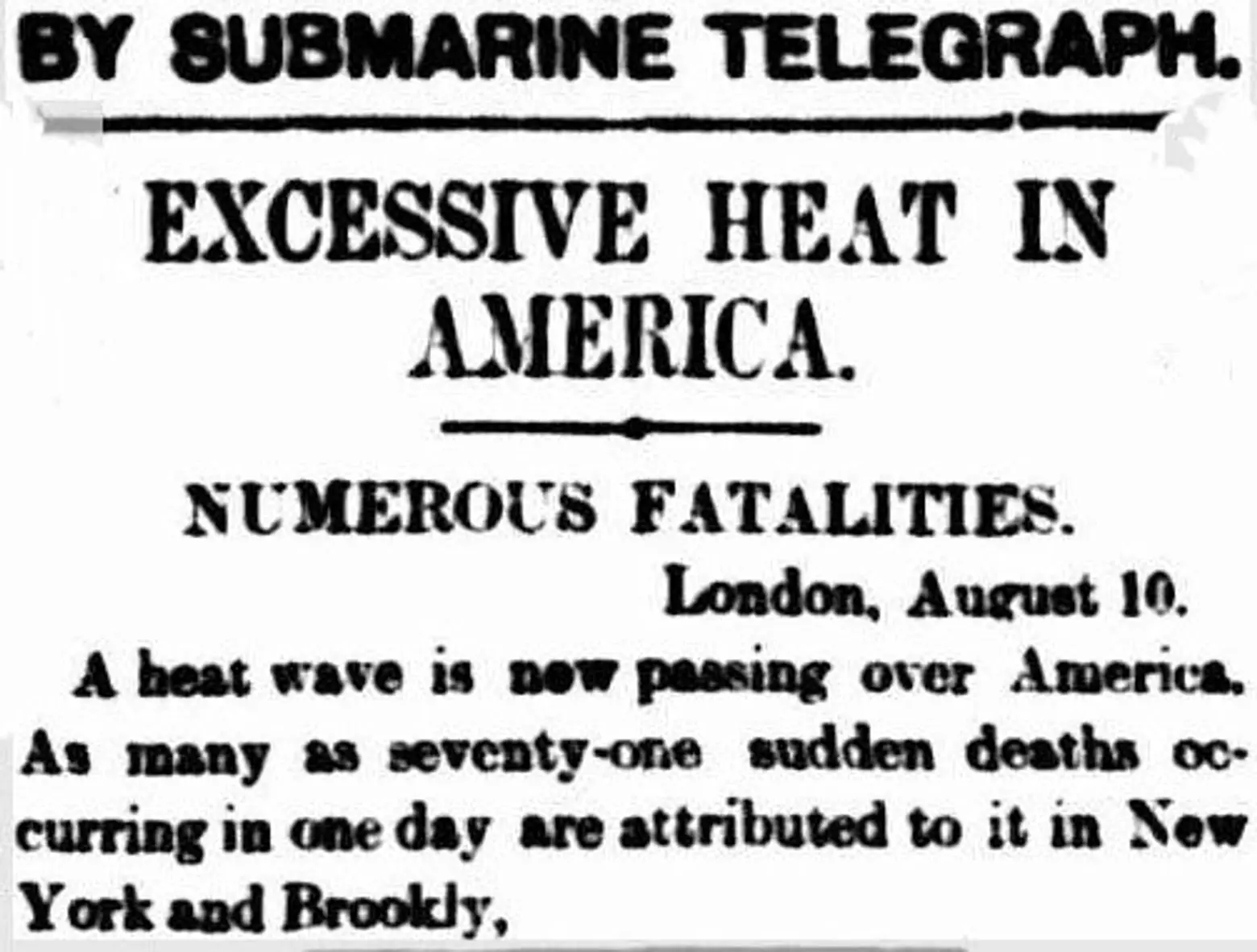

New Yorkers have been uncapping with and without permission since the “Great Heat Wave of 1896,” which lasted 10 days and resulted in more than 1300 fatalities. On that occasion, the hydrants were technically opened to cool down the streets and help wash away accumulating piles of garbage, but this didn’t stop New Yorkers, especially the city’s youngsters, from running into the street to cool down. Over the coming decades, the practice of uncapping continued to gain popularity but not without complaints. These complaints would eventually lead city officials to ban this spontaneous form of summer fun.

Although uncapping was no longer legal, throughout the twentieth century, the practice persisted. As a result, in the late 1950s, six city agencies met to come up with a solution. They eventually agreed to start distributing free spray caps. To kick off the campaign, the Police Athletic League distributed 1000 free spray caps citywide in the summer of 1960. With each spray cap, a wrench was also given to an “authorized responsible adult” in the neighborhood to help turn the cap on and off as needed. With fire hydrants far outnumbering available spray caps, however, the problem was not solved.

Image via FDNY

Image via FDNY

During one heatwave in the summer of 1972, so many children uncapped hydrants that water pressure started to drop in neighborhoods across the city. In an effort to lower water consumption, the Mayor’s office toured neighborhoods, encouraging residents to use spray caps instead, which release only 25 to 28 gallons per minute versus as much as 1700 gallons per minute. Unfortunately, just as most kids would choose a bigger rather than smaller waterpark, the same logic applies to uncapping. Why splash in a mere 25 gallons per minute when you can have 1700?

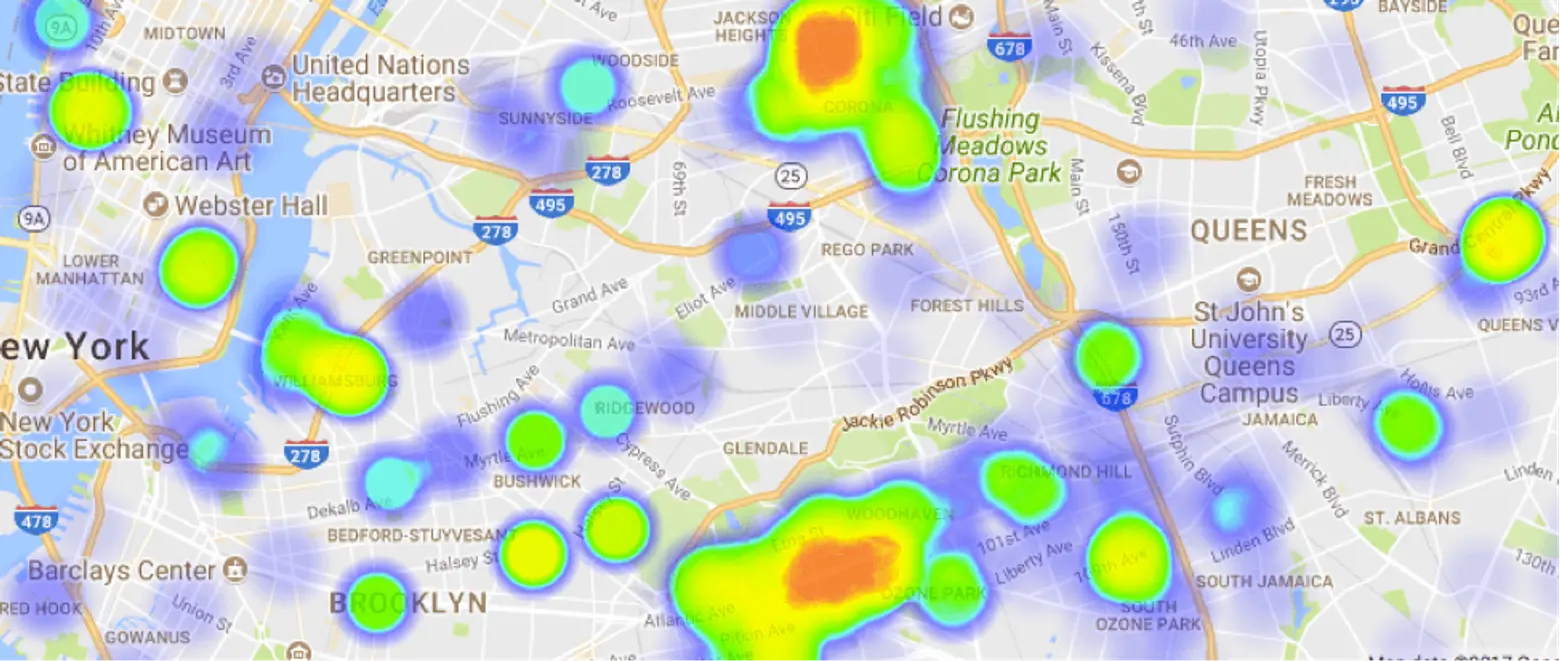

Uncapping’s hot spots

While uncapping’s hotspots have shifted over time, by and large, neighborhood’s with a higher percentage of people living on lower incomes and in public housing projects have always reported higher incidents of uncapping. As the above map (generated using data provided from 311 complaints about uncapping) reveals, Hell’s Kitchen, the Lower East Side, the South Side of Williamsburg, Bushwick, Bed-Stuy, Jackson Heights, and Woodhaven are among the city’s uncapping hotspots. Several locations in Upper Manhattan and the Bronx also report high numbers of 311 complaints about uncapping. By contrast, in other neighborhoods, including the Upper East Side where most residents leave for the summer or ship their children off to overnight camps, uncapping complaints are virtually nonexistent.

The legal and environmentally friendly way to uncap

Not surprisingly, as environmental awareness has grown, concerns about uncapping have not only increased but also taken a new form. While early New Yorkers frequently complained about road blockages and flooding, today’s 311 complainers are just as likely to point out that uncapping wastes precious water reserves at a moment when many people in the world—who don’t live in a city with its own pristine water reservoirs—barely have enough water to carry out basic cooking and cleaning tasks.

Fortunately, for those who want to uncap, it is still possible to do so legally and with limited environmental impact. Those free spray caps first distributed in 1960 still exist, so before you don your swimsuit and run into the street, get in touch with your local fire station. For no charge at all, a local fireman will install or lend you a spray cap to reduce your local hydrant’s flow to 25 gallons per minute and don’t worry, installation of the spray cap is part of the deal. While a spray cap may feel more like a sprinkler on a suburban lawn than a specular street-level waterpark, your eco-friendly neighbors will at least be less disapproving.

Finally, if you’re thinking about uncapping without the help of local firemen, think again. Uncapping without a spray cap does lower water pressure. If a fire does occur, fire crews may not have enough water pressure to respond to the blaze. Also, bear in mind that if you decide to splash without a cap and are caught, you may face up to a $1000 fine or 30 days in jail.

RELATED: