NYC neighborhoods made for workers: The history of Queens’ Steinway Village and the Bronx Co-ops

While immigration, urban planning, and the forces of gentrification are certainly key factors in how NYC’s neighborhoods have been shaped, New Yorkers’ patterns of work, their unions, and in some instances, even their employers have also played a role in the development of several of the city’s established neighborhoods. To mark May Day, 6sqft decided to investigate two of the city neighborhoods that were quite literally made for workers—the Van Cortlandt Village area of the Bronx and the Steinway neighborhood in Astoria, Queens.

“The Coops” in Van Cortlandt Village, Bronx

The Coops today, via Wiki Media

The Coops today, via Wiki Media

The “Allerton Coops,” sometimes simply known as the “The Coops,” were originally built by the United Workers’ Association in the 1920s. The union was primarily composed of secular Jewish needle-trade workers with far-left political convictions who sought to improve the living conditions of their members by constructing affordable housing in a safe and engaged community setting.

While the United Workers are often credited with building all the workers co-ops in the Bronx, in fact, there were several labor organizations that drove the construction of co-ops in the Bronx in the 1920s. The Shalom Aleichem Houses, which were also known as the Yiddish Cooperative Heimgesellschaft, were driven by the vision of the Workmen’s Circle. The Shalom Aleichem Houses included 229 apartments as well as several common spaces dedicated to education and the arts, including artist studios. Notably, while “Shalom Aleichem” translates into “peace be upon you,” the name was chosen because it also happened to be the pen name of well-known late-19 to early-20th-century Ukrainian Yiddish writer Solomon Naumovich Rabinovich, whose works included “Tevye the Milkman,” the source text for “Fiddler on the Roof.”

The largest housing initiative built by a union in the Bronx in the 1920s to 1930s was the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America complex at the edge of Van Cortlandt Park. The complex was designed by Springsteen and Goldhammer for 308 families and included an elaborate formal garden. Tenants were able to purchase their apartments for $500 a room and could finance most of the cost through a special fund set up to assist workers. Maintenance costs were $12.50 a room per month.

While providing workers with safe and affordable housing was the primary aim of the United Workers, Workmen’s Circle, and Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, the co-ops also offered other essential services. Indeed, to further support tenants, the Co-ops, the Shalom Aleichem Houses, and the Amalgamated also set up cooperative stores that offered groceries at a discount. By the late 1920s, the workers co-op movement had also rolled out another service for workers and their families that remains a New York City tradition—the upstate summer camp.

Steinway Village, Queens

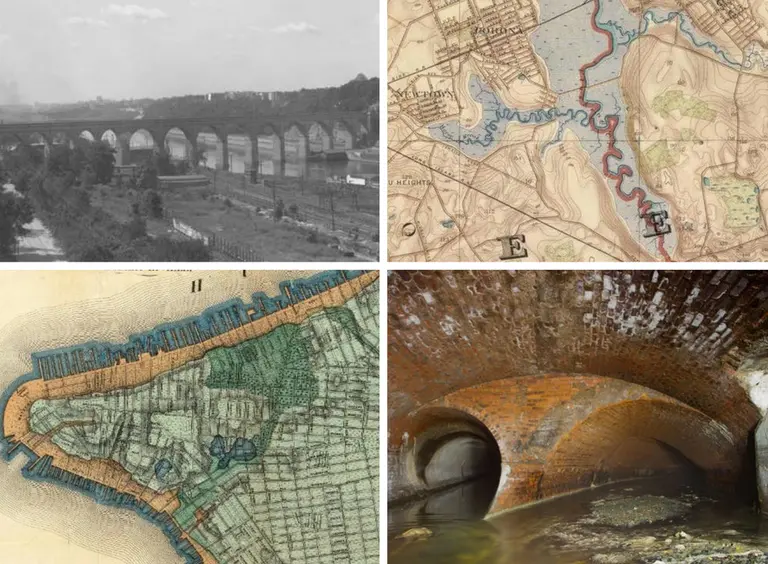

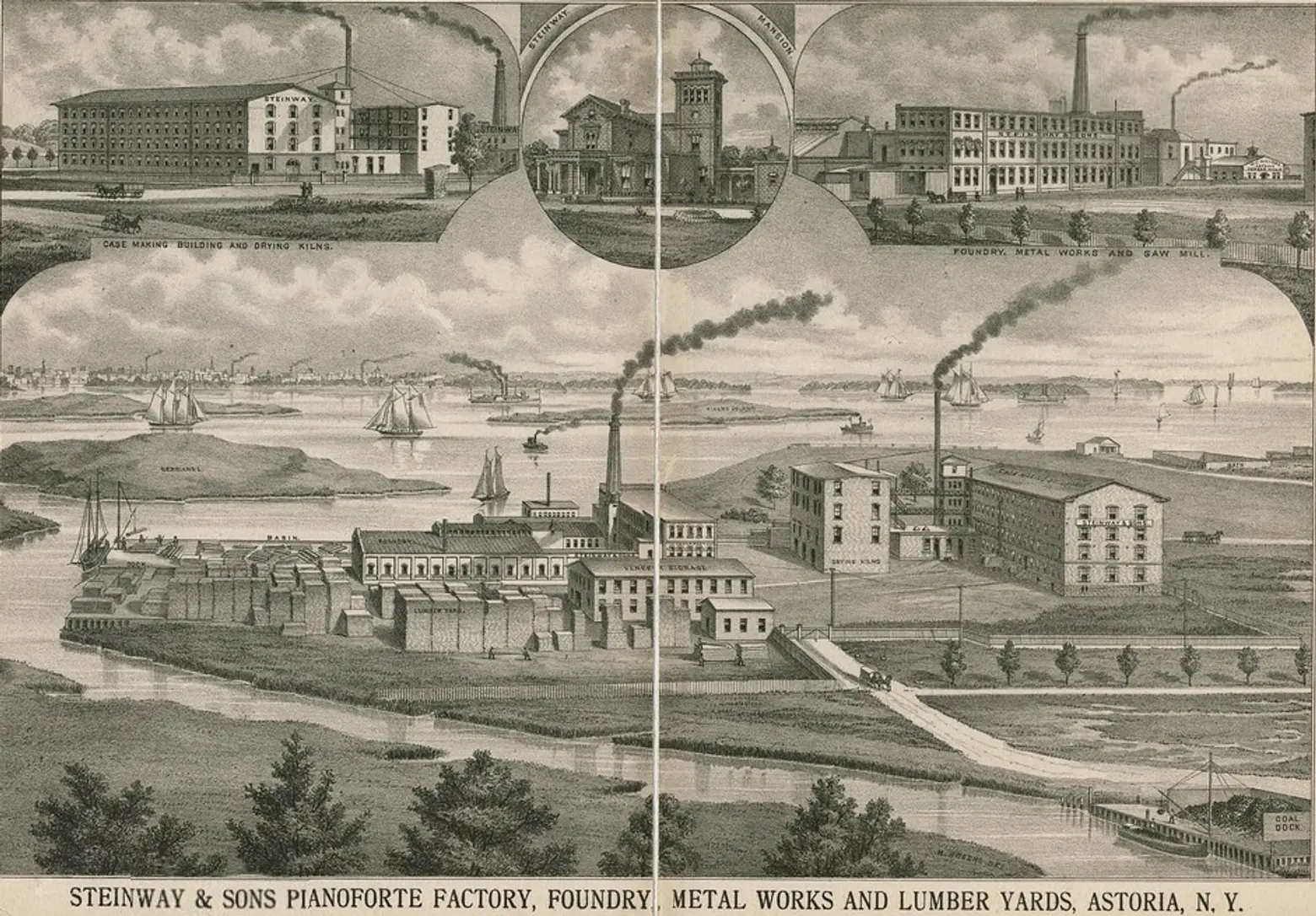

Steinway & Sons piano factory in 1875, via Queens Borough Public Library

Steinway & Sons piano factory in 1875, via Queens Borough Public Library

While workers in the Bronx were settling into new homes built with the support of their unions, in Astoria, Queens many workers and their families were already living in worker-designated housing but with a very different history.

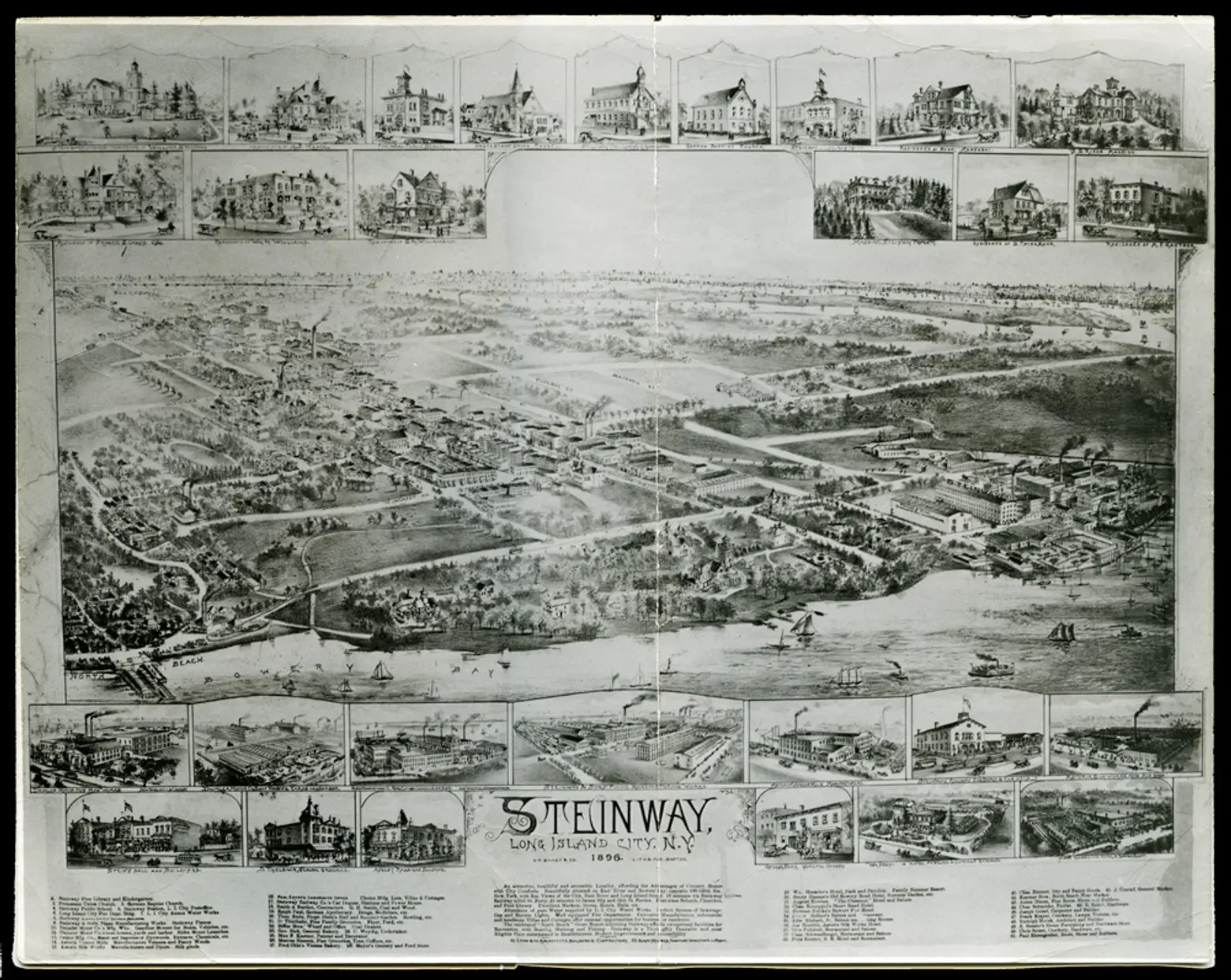

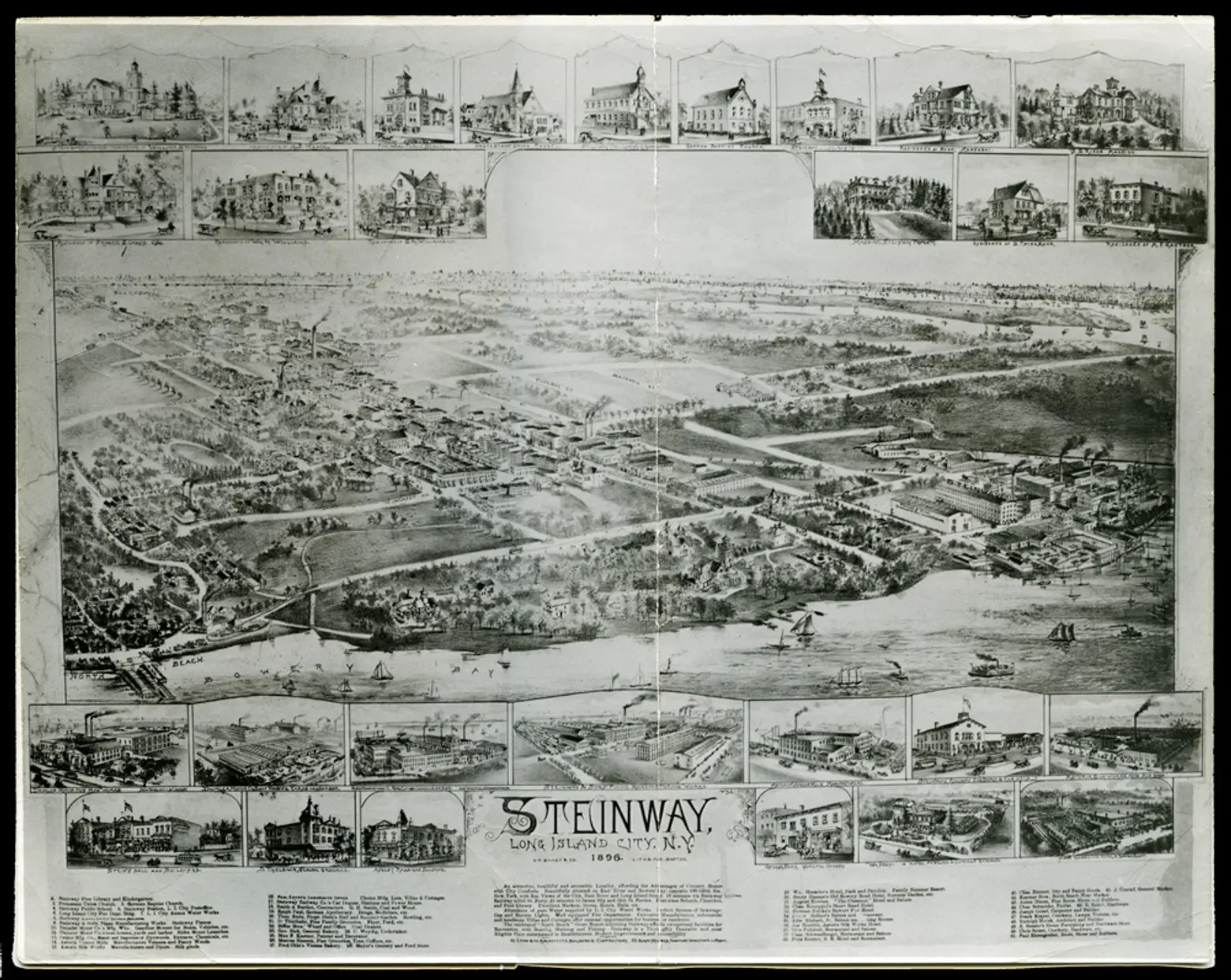

Map of Steinway Village in 1896. G. H. Bailey & Co. Courtesy of Henry Z. Steinway Archive, Smithsonian

Map of Steinway Village in 1896. G. H. Bailey & Co. Courtesy of Henry Z. Steinway Archive, Smithsonian

Steinway & Sons are most well known for their pianos but at one point, the family also had aspired to get into the real estate business. Originally, the Steinway’s piano factory was located in Manhattan, but given the difficult living conditions on the Lower East Side (and perhaps due to rising concerns about labor unrest), the family chose to relocate to Queens in 1870. However, in addition to moving their piano factory, they decided to also move their workers and their families. The Steinway’s intentional neighborhood would eventually include 29 two-story red-brick row houses located at 41st Street and 20th Avenue in Astoria, Queens. The houses were completed between 1874 and 1875.

In 1974, the Landmarks Preservation Commission attempted to establish a Steinway Historic District. In the end, the proposal was squashed by a majority of local residents who didn’t want their homes to become part of a historic district. Notably, at the time, the nullification of the Steinway Historic District was only the second occasion on which a landmark designation has been disapproved by the Board of Estimate.

Current Housing Initiatives for Workers

The newly restored Hahne & Company building in downtown Newark, where Audible workers could live rent-free. Via Hahne & Co. and Bozzuto

The newly restored Hahne & Company building in downtown Newark, where Audible workers could live rent-free. Via Hahne & Co. and Bozzuto

In New York City, housing continues to pose a major obstacle to workers, including essential workers from teachers to police officers to nurses. To help ensure that middle-income workers can afford to live in the city limits, the city continues to prioritize city workers (e.g., police officers and teachers working for the DOE) in housing lotteries. Several New York City hospitals also offer subsidized housing to staff, including interns, doctors, and nurses. Recently, however, the region has also seen a resurrection of the Steinway family’s approach to housing.

Last year, Amazon rolled out a housing initiative for workers at its Audible headquarters in Newark. The company offered 20 employees a chance to get $2,000 a month in free rent for a year on the condition that they sign a two-year lease in a recently restored building in downtown Newark. In the end, 64 of the company’s 1,000 employees applied with the lottery winners ending up with $500 a month apartments that generally substantially larger than their former homes in places like Brooklyn and Manhattan. Unfortunately, this seemingly too-good-to-be-true housing story isn’t a forever story: Audible’s housing lottery winners will eventually be expected to pay market rent for their units.

RELATED: