‘Peeling’ away the history of NYC’s banana docks

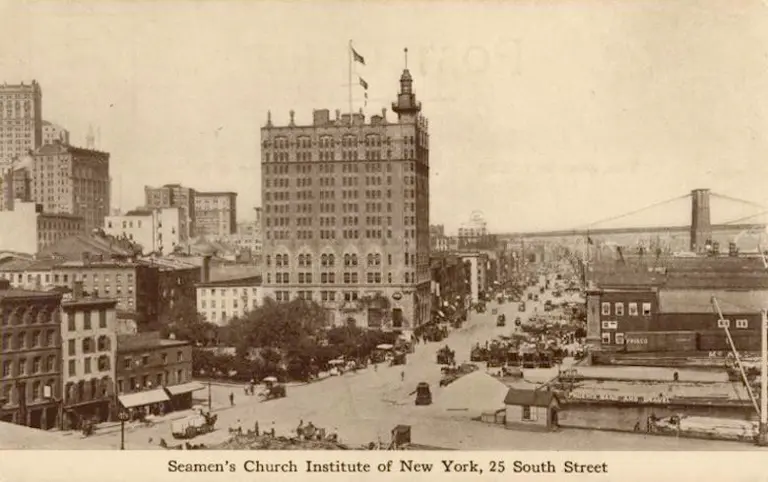

“Banana Docks, New York” c. 1906. Via The Library of Congress

If you’ve ever grabbed a bushel of bananas at your corner bodega, then you’ve nabbed a few of the 20 million bananas distributed around NYC every week. Today, our bananas dock at small piers in Red Hook, or, more often, make the journey by truck from Delaware. But, from the late 19th century until well into the 20th, New York was a major banana port, and banana boats hauled their cargo to the city’s bustling Banana Docks on the piers at Old Slip.

Surveying that cargo in August 1897, The New York Times wrote that the banana trade thrived in New York year-round, but the bulk of bananas hit the five boroughs between March and September. “They are brought to New York in steamers, carrying from 15,000 to 20,000 bunches…There is quite a fleet of small steamers engaged almost exclusively in the banana trade, and during the busy season many more steamers of greater size are employed.”

“New York, Banana Docks.” c. 1890 – 1910. Via The Library of Congress.

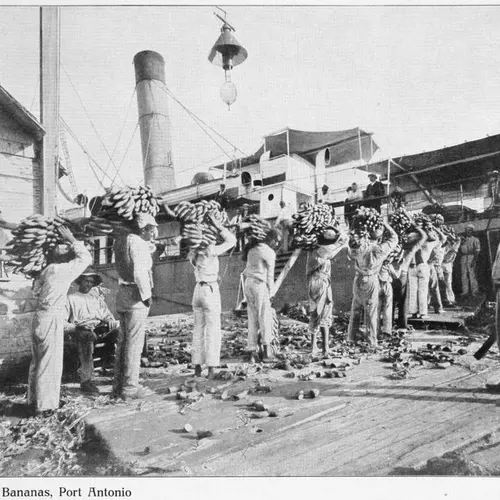

As New York’s “old time banana handlers” plied Lower Manhattan’s docks and piers, bringing bushels ashore, they were not alone in the harbor. Neighborhood children, including Alfred E. Smith, future four-term Governor of New York and loyal son of South Street, took turns diving off the banana docks to catch stray fruit. Remembering a childhood spent at the Seaport, Smith recalled in his autobiography, “In the warm summer days it was great fun sliding under the dock while the men were unloading the boatloads of bananas from Central America. An occasional overripe banana would drop from the green bunch being handed from one dock laborer to another, and the short space between the dock and the boat contained room enough for at least a dozen of us to dive after the banana.”

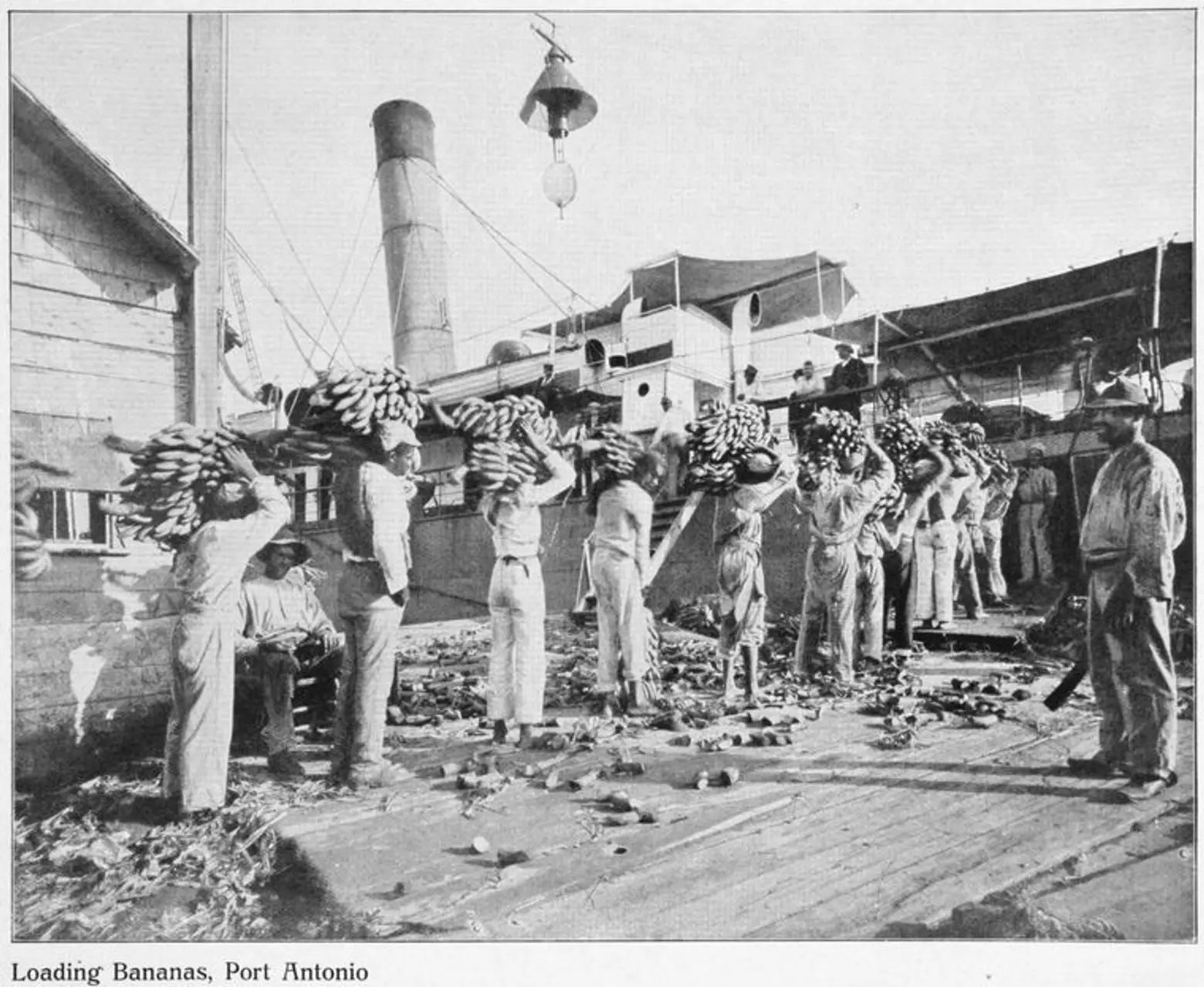

The bananas that Smith dove for are different than the Cavendish bananas we eat today. At the time, New Yorkers could choose from large red bananas from Cuba, high-end bananas from Jamaica, and the once-ubiquitous Gros Michel, or Big Mike from Southeast Asia and Central America.

“Loading Bananas” from “Picturesque Jamaica” c. 1900. Via Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, NYPL Digital Collection.

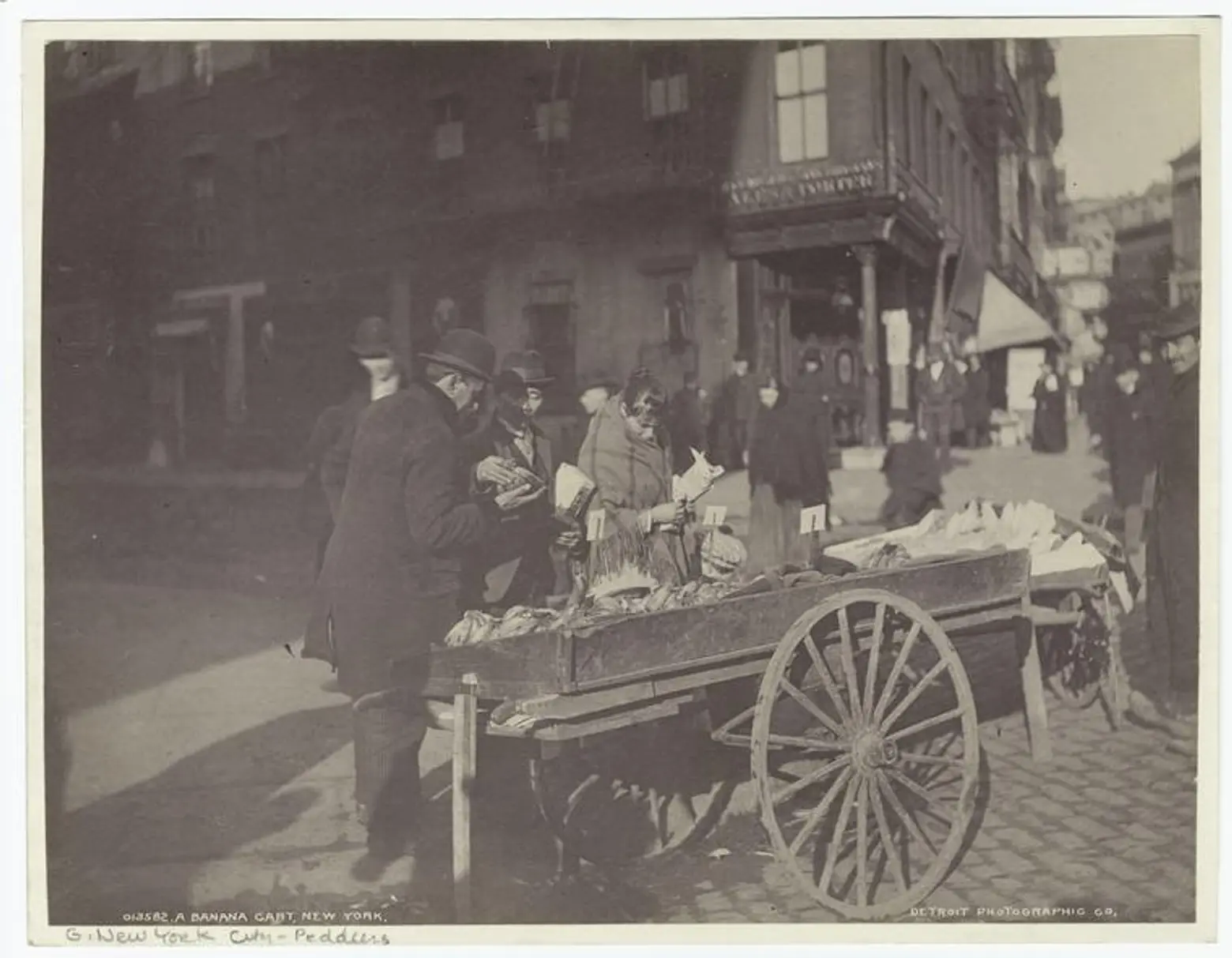

When New Yorkers weren’t diving for bananas, they were dropping them. In the late 19th century, banana peels had become a genuine menace to society. An 1875 column in the Times titled “Dangers of the Streets” decried “the dangerous practice of throwing oranges or bananas on public thoroughfares.” The column squawked, “In the neighborhood of West and Greenwich Streets, where traffic to and from the ferries is greatest, it is extremely dangerous for persons to move along the sidewalks at all, in consequence of the recklessness with which the custom is followed.”

Slipping on a banana peel was considered such a real danger, that Teddy Roosevelt himself, who was then President of the New York City Board of Police Commissioners, declared a “war on the banana skin” in 1896. Roosevelt instructed his officers to enforce a law already on the books which held that anyone discarding fruit in public places in New York City “which, when stepped upon by any person is liable to cause…him or her to slip and fall shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor.” Those who would inappropriately dispose of fruit within the city limits paid a heavy price: a fine between $1 and $5 or up to 10 days in jail!

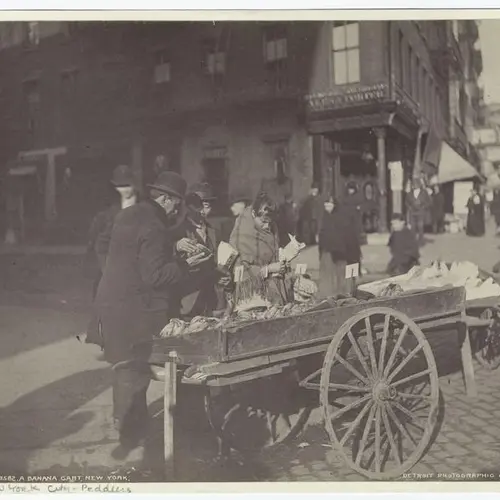

“Banana Cart, New York.” c 1900 – 1909, via NYPL Digital Collections.

But some New Yorkers turned slipping on a banana peel into an art form – and a cash cow. In 1910, Mrs. Anna H. Strula had collected nearly $3,000 in damage suits after claiming she had suffered 17 accidents in the space of four years. A skeptical New York Times, reporting that she had been arrested for grand larceny in connection to her accident claims, joked that “banana peels seemed literally to dog her footsteps.”

Three thousand dollars was one thing, but when it came to banking on bananas, Antonio Cuneo was the undisputed “Banana King of New York.” Cuneo, who arrived in New York a penniless Italian immigrant, rose to make a fortune in fruit. Poignantly, bananas and milk were among the first meals that newly arrived immigrants were served at Ellis Island.

Cuneo was top banana among the city’s fruit shipping and distribution firms. From his office at 54 Broadway, Cuneo ran the Cuneo Banana Company, also known as the Panama Trust. Ironically, it was Panama Disease that would ravage his wares. Panama Disease, named for the nation where it was first discovered, destroys banana plants from the inside out. The disease began seriously affecting the Big Mike banana crop in the early 1900s, and eventually led to the near-total extinction of Big Mikes by 1960.

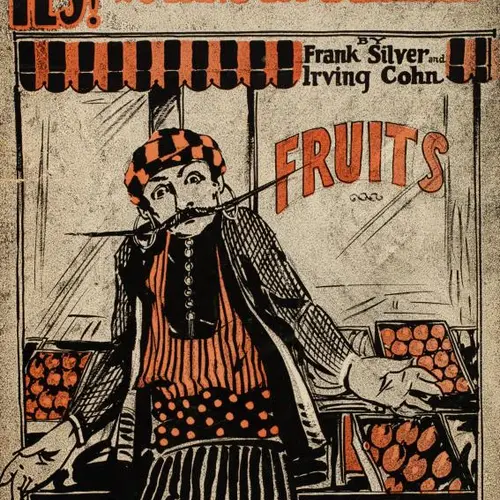

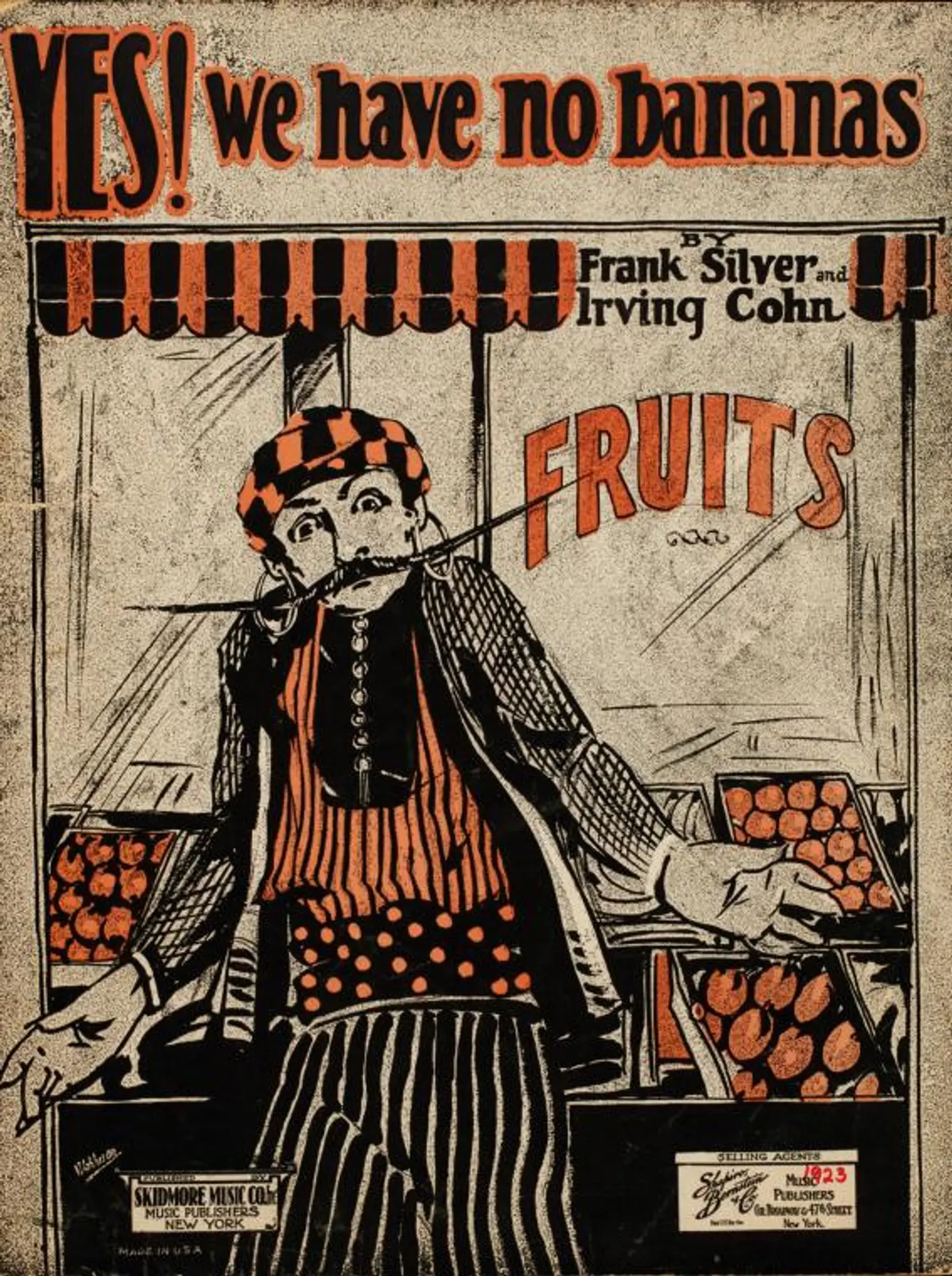

“YES! We have no bananas.” 1923. Via NYPL Digital Collections

“YES! We have no bananas.” 1923. Via NYPL Digital Collections

In fact, that’s the origin of the song “Yes! We Have No Bananas!,” which spent a stunning five straight weeks at number-one in 1923. The story goes that one day on the way to work, New York tunesmiths Frank Silver and Irving Cohn stopped for bananas and were told by a Greek grocer, “Yes! We have no bananas.” There were no bananas because Panama Disease had been steadily destroying Big Mikes since at least 1910.

But what brought the blight? Blame Big Banana. The United Fruit Company – a ruthless corporate empire that ran at least 12 “Banana Republics” throughout the Western Hemisphere, propped up bloody dictatorial regimes, and helped finance both the Bay of Pigs Invasion and the CIA coup in Guatemala in 1954 – came to control up to 90% of banana market, and made sure that market was devoted entirely to the Big Mike.

Since United Fruit favored extreme monoculture, when Panama Disease hit one crop, it could spread easily to them all. So, the Big Mike succumbed, and growers turned to the Cavendish, which we eat today (though similar failure to diversify now threatens the Cavendish).

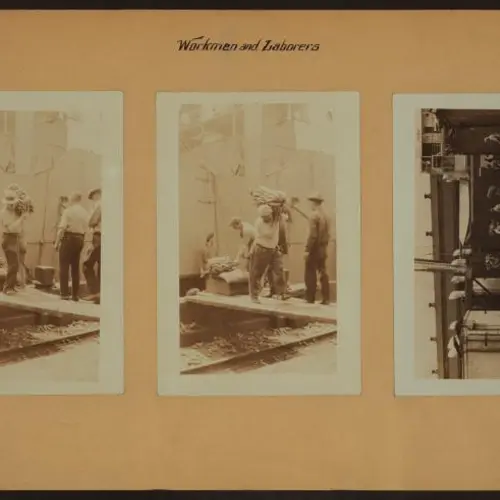

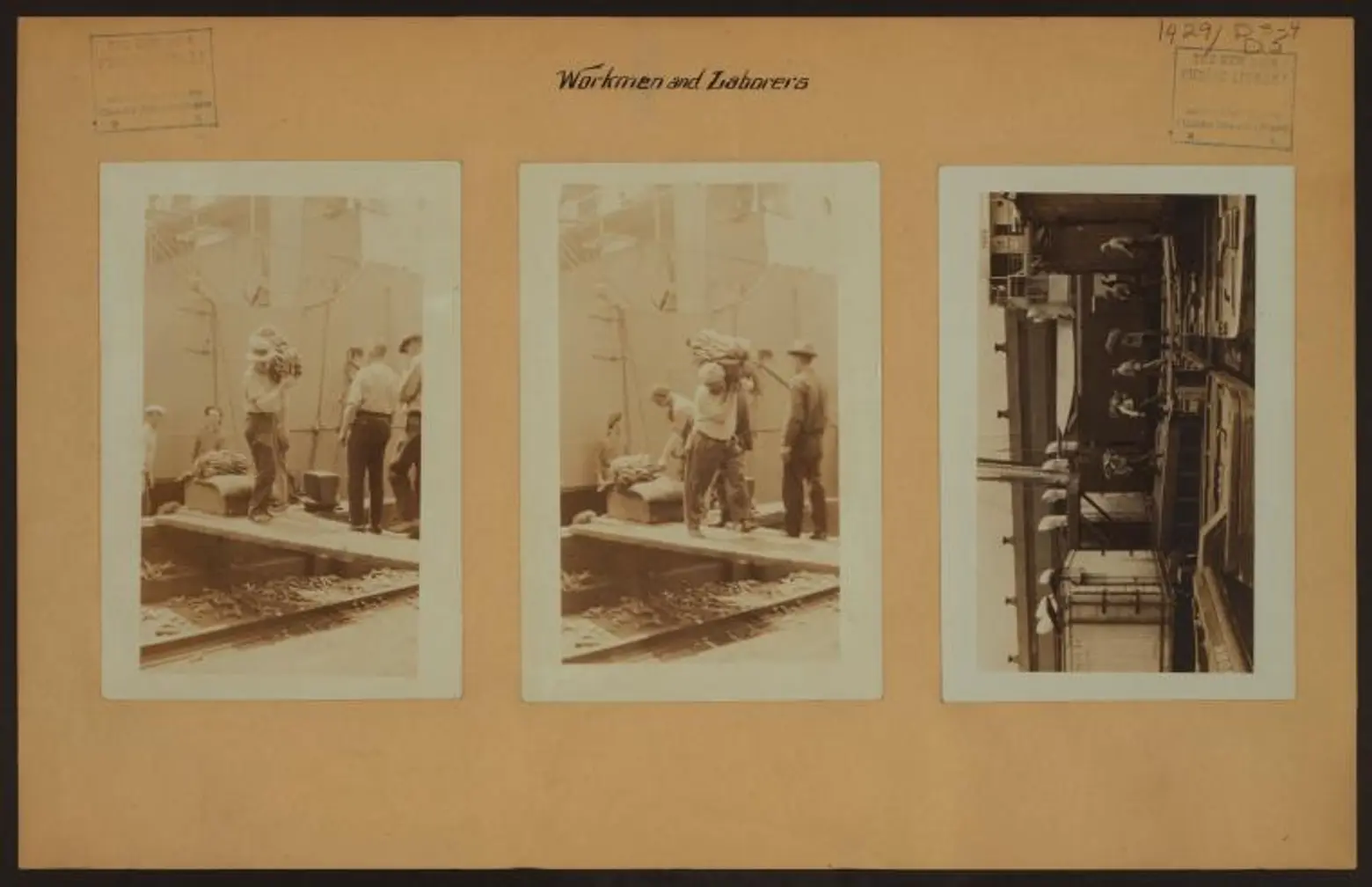

“Workmen and laborers – [Unloading bananas on the East River Pier No. 16 – United Fruit Company – S.S. Yoro.]. 1925 – 1926. via NYPL Digital Collections

As went Big Mike so went New York’s Banana Docks. In fact, United Fruit itself pulled the ultimate “Banana Split” in 1971. That year, the banana behemoth abandoned its Weehawken terminal, from which it brought millions of bananas through the Port of New York, for cheaper accommodations in Albany. In 1987, longshoremen unloaded cargo from Manhattan’s last banana boats, docked at Pier 42.

Today, the Red Hook piers handle about one-fifth of New York’s bananas. Al Smith’s banana docks have gone the same way as his beloved Fulton Fish Market: to Hunts Point, in the Bronx, where local distributors in the tradition of Antonio Cuneo ready your bunch for its place at the fruit stand on the corner.

RELATED:

- From beavers to banned: The history of New York City’s fur trade

- 10 places with ties to New York City’s maritime history

- Latin in Manhattan: A look at early Hispanic New York

+++

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.