Pubs, parades, and politicians: The Irish legacy of the East Village and Greenwich Village

Photo of White Horse Tavern (bottom left) courtesy of Wikimedia; Photo of the Merchant’s House Museum (bottom right) courtesy of Village Preservation on Flickr

For many, celebrating Irish American heritage in March brings one to Fifth Avenue for the annual St. Patrick’s Day Parade, or perhaps a visit to St. Patrick’s Cathedral. But for those willing to venture beyond Midtown, there’s a rich Irish American history to be found in Greenwich Village and the East Village. While both neighborhoods became better known for different kinds of communities in later years – Italians, Ukrainians, gay men and lesbians, artists, punks – Irish immigration in the mid-19th century profoundly shaped both neighborhoods. Irish Americans and Irish immigrants played a critical role in building immigrant and artistic traditions in Greenwich Village and the East Village. Here are some sites connected to that great heritage, from the city’s oldest intact Catholic Church to Irish institutions like McSorely’s Old Ale House.

Photo by Tony Hisgett on Flickr

Churches

Greenwich Village and the East Village contain no shortage of historic churches rooted in the Irish American experience. St. Joseph’s Church at 365 Sixth Avenue (Washington Place), built in 1833, is the oldest intact Catholic Church in New York City and the first built for a predominantly Irish congregation (the earlier Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Mulberry Street was burnt down and largely rebuilt). From its earliest days St. Joseph’s largely served Irish immigrants and their children, who began streaming into the neighborhood in the early 19th century. Even after Italian immigrants far outnumbered the Irish in Greenwich Village by the early 20th century, St. Joseph’s maintained its connections to parishioners from the Emerald Isle.

In its early years, St. Joseph’s dedicated much of its work to supporting struggling Irish families, many of whom had tough jobs as domestics or in the building and shipping trades. As time went on and Irish Americans became more established, the church’s focus expanded. Thomas Farrell, the pastor of the church from 1857 to 1880, spent his tenure advocating for emancipation and the political rights of African Americans. In his will, Farrell wrote: “I believe that the white people of the United States have inflicted grievous wrong on the colored people of African descent, and I believe that Catholics have shamefully neglected to perform their duties toward them. I wish, then, as a white citizen of these United States and a Catholic to make what reparation I can for that wrong and that neglect.”

When he died, Farrell gave five thousand dollars to found a new parish for the city’s black community, which became the nearby Church of St. Benedict the Moor at 210 Bleecker Street in 1883. This church was the first African American Catholic church north of the Mason-Dixon line. Farrell also pushed the envelope on church teachings, advocating for public education, questioning celibacy for priests and papal infallibility, and publicly supporting the Italian government taking control of Rome in 1870 and ending a long history of papal control. In the 1980s, the church also hosted the first meeting of the Gay Officer’s Action League (GOAL), founded by Sgt. Charles Cochrane, the first openly-gay NYPD officer.

St. Bernard’s Church at 336-338 West 14th Street (8th-9th Avenues) was built in 1873 by the great Irish church architect Patrick Charles Keely. Historically, St. Bernard’s Parish was considered one of the most important parishes in the city. In the 1870s, the congregation, primarily composed of Irish immigrants and their descendants, was rapidly outgrowing its smaller church on 13th Street at Tenth Avenue, so the decision was made to construct a new, larger structure nearby. The Irish-born Keely had become famous for his church designs across the country, numbering over 600 by the time of his death in 1896, including every Catholic Cathedral in New York State at the time except St. Patrick’s.

Though he designed for several different denominations, he built most prolifically for the Catholic Church. St. Bernard’s was designed in the Victorian Gothic style, which was in fashion for Catholic churches at the time; the twin towers, triple-portal entrance, and rose window inset with pointed arch reveal a masterful blending of French and English influences to create this uniquely beautiful church.

By 1910, St. Bernard’s was one of the largest churches in the city, with over 10,000 parishioners. In the 20th century, a Spanish immigrant community on the Far West Side began to worship there as well, and by the 21st century, the church served a predominantly Latin American population, renamed Our Lady of Guadalupe at St. Bernard’s.

Photo by Beyond My Ken on Wikimedia

St. Veronica’s Church at 149-155 Christopher Street (Washington/Greenwich Streets) was built in 1890 to serve the growing Irish American population along the Greenwich Village waterfront. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Hudson in this area was a thriving port, and those who worked the waterfront were overwhelmingly of Irish extraction. Like St. Bernard’s, St. Veronica’s pews were packed in its early decades, with over 6,000 parishioners when it opened. In the late 20th century, as the surrounding neighborhood became the center of New York’s gay community, the church struggled with how to accommodate a population whose lives in some ways contradicted church teachings. The church has the first known memorial to those who died of AIDS and opened one of the first hospices for People With AIDS in 1985. In the 21st century, the church’s congregation dwindled, and it was first downgraded to a chapel of Our Lady of Guadalupe/St. Bernard’s, and then was closed. Its fate remains uncertain, though landmark designation in 2006 should protect at least the exterior of the building.

St. Brigid’s Church at Avenue B and 8th Street was built in 1848 and, like St. Bernard’s, designed by Patrick Charles Keely. Built at the height of the Irish potato famine and the beginning of large-scale Irish immigration to New York, it was known as the “Irish Famine Church.” Before the Hudson River’s ascendance as the heart of New York’s waterfront, it was the East River that was the center of the city’s shipping trade. St. Brigid’s mostly served a congregation connected to that industry, which like along the Hudson River waterfront consisted predominantly of Irish workers. Appropriately, Brigid was the patron saint of boatmen.

In the mid-19th century, the church was the source of many of the men of the 69th New York State militia’s 2nd regiment of Irish Volunteers; in the late 1980s, the church took the controversial stand of feeding and helping protestors, squatters, and the homeless involved in the Tompkins Square Riots. In the early 2000s, the church was slated for closure despite vocal objections of the local community after it became clear that structural repairs were needed. However, a $20 million anonymous donation not only allowed the church to reopen but undergo a thorough renovation and restoration, and the church now operates as St. Brigid-St. Emeric, absorbing a congregation which formerly worshipped on Avenue D.

Photo © James and Karla Murray for 6sqft

Pubs

No survey of Irish American heritage would be complete without a look at some of their great and gathering places for food and drink. Two of the most legendary New York City taverns of Irish lineage are located in Greenwich Village and the East Village.

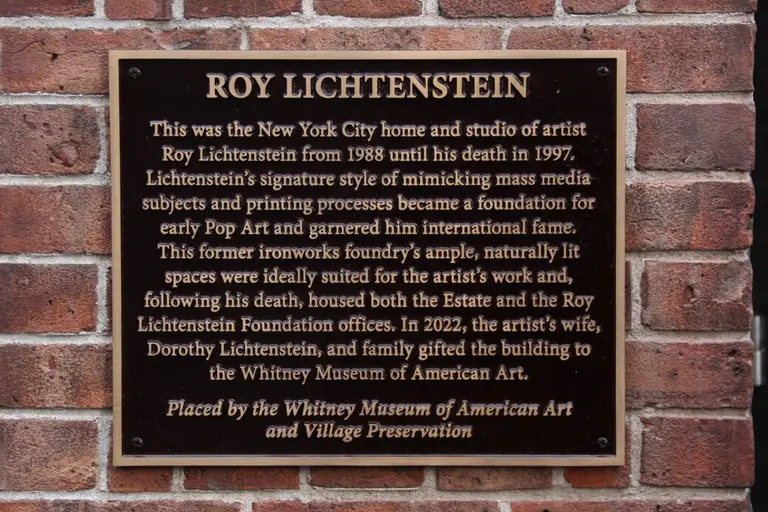

Depending on whom you believe, McSorley’s Old Ale House at 15 East 7th Street was either founded in 1854 (according to McSorley’s) or around 1860 or 1861 (according to Department of Buildings records indicating when the present structure was built). In either case, it’s been a beloved fixture of the New York cultural and literary scene for well over a century and a half, and a favorite of artists and writers. It was also one of the last holdouts in the city to admit women in 1970 – after considerable agitation from the courts, legislature, and feminists (it was another decade and a half before the bar installed a ladies room).

Founded by Irish Immigrant John McSorley, the bar has changed little in decades; its floors are still covered in sawdust, and memorabilia on the walls dates back a century or more. If you’re wondering what it looked like in days gone by, just check the 1912 painting McSorley’s Bar by artist John Sloane; other than the garb of the waitstaff and patrons, not much has changed (and in some cases even that hasn’t!).

Photo by Seth Fox on Wikimedia

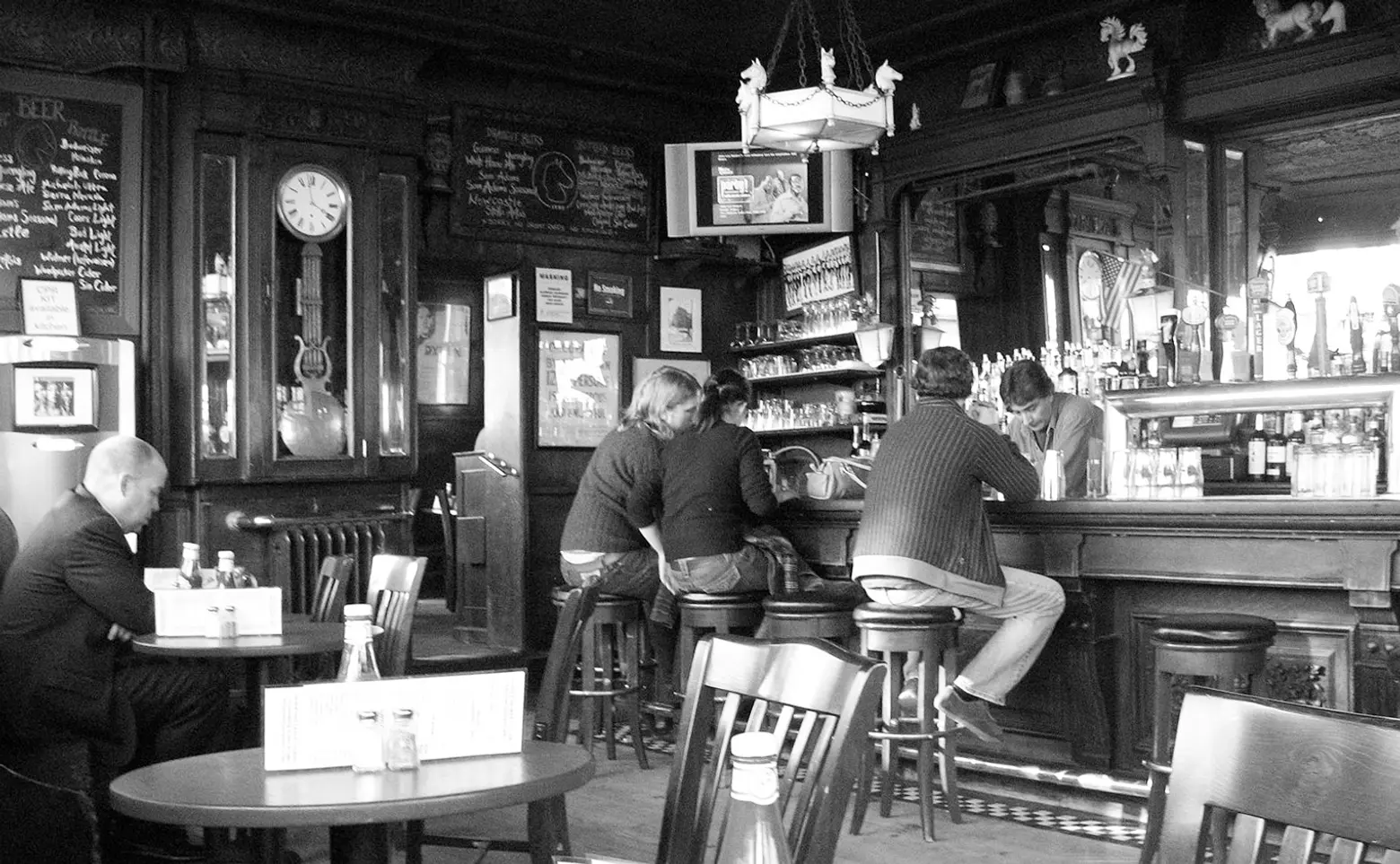

Another classic Irish gathering spot is the White Horse Tavern at 567 Hudson Street. Opened in 1880 to serve a predominantly Irish longshoreman clientele from the surrounding waterfront neighborhood, it became a center of labor organizing and agitation by the early 20th century, as the dockworkers organized around various union and left-wing movements and argued their cases and positions over drinks. After World War II, however, the bar became a center for New York’s literati, with local residents James Baldwin, William Styron, Norman Mailer, Anais Nin, Jack Kerouac, Jane Jacobs, and Allen Ginsberg, among others, frequenting the spot.

Perhaps hard-drinking Welsh poet Dylan Thomas cemented the Horse’s reputation as the place for the literary class to go when he in 1953 drank himself to death there. Thomas’ associations with the pub attracted the next generation of creative thinkers to the watering hole, which included his namesake, Bob Dylan, as well as Jim Morrison, Peter, Paul and Mary, and the Clancy Brothers.

Domestic workers

For poor and working-class Irish and Irish American women in the 19th and early 20th centuries, one of the best opportunities available to them was to serve as domestic workers in the home of an affluent family. While this often meant no more than an afternoon off per week, being on call 24-hours-a-day, and climbing up and down stairs all day carrying water, coals and ash, and refuse and laundry, it did mean avoiding the perils of often overcrowded and unsanitary tenement life and frequently dangerous factory work and was considered a ‘respectable’ profession for women.

While the story of the lives of most of these women has been lost to history, one surprising place where they are kept alive is the Merchant’s House Museum at 29 East 4th Street. New York’s only intact preserved 19th-century merchant family house on the inside and out, MHM not only endeavors to tell the story of the Tredwell family which owned the house but the Irish servants who made it run. You can learn more about the lives they lead, their role within the house, and how they managed to save money from their meager incomes to send back to support relatives in Ireland.

Alfred Smith at the opening of Yankee Stadium, April. 18, 1923, Courtesy of the George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress)

Politicians

It was not long after arriving in New York that the Irish began to make their way up the political ladder, becoming a powerful force in the city’s electoral politics for generations. Two of the city’s most prominent and successful Irish American politics called the Village home.

Alfred E. Smith was not only the first Catholic major party candidate for President but the first Irish Catholic as well. Born on the Lower East Side, he worked his way up the electoral ladder, starting as an Assemblymember, New York Country Sheriff, President of the Board of Aldermen, and finally New York State Governor. After several attempts, in 1928 he secured the Democratic nomination for President but was bested by Herbert Hoover, who soon presided over the stock market crash and the worst economic depression in American history.

After his lopsided defeat in the 1928 election (clearly powered in part by anti-Catholic sentiment), Smith retired from electoral politics and moved into the newly built elegant apartment building at 51 Fifth Avenue at 12th Street in Greenwich Village. From there he helped lead the consortium responsible for the building of the Empire State Building, the tallest building in the world from its opening in 1931 until 1973, and a continuing symbol of New York City.

James “Gentleman Jim” Walker was a protégé of Al Smith’s who served as Mayor of New York City during the “Jazz Age” from 1926 to 1932. Often called ‘Beau James,’ he embodied the flash and sparkle of that era, and while not New York City’s first Irish Catholic mayor, he was arguably its most flamboyant. Walker, whose father was born in Ireland, pursued the unusual dual career track of becoming both a lawyer and a Tin Pan Alley songwriter. His career ambitions eventually focused on his former vocation, as he began to climb the electoral ladder in 1910, starting with the State Assembly like his mentor Smith. Like Smith, Walker was a staunch advocate of creating a social safety net, repealing blue laws prohibiting baseball games on Sunday, and legalizing boxing, and was an equally staunch opponent of Prohibition and the revived Klu Klux Klan, which was increasingly active in its anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant, anti-Semitic, and racist campaigns.

Walker was known for cavorting with chorus girls, tolerating speakeasies, and flouting conventional morality while greatly expanding the city’s subway, sanitation, and transportation systems. He grew up in the Irish middle-class enclave of St. Luke’s Place in Greenwich Village at No. 6, where he continued to live through his mayoralty; the city playground across the street is today named in his honor.

The Parade

While New Yorkers have for well over a century celebrated St. Patrick’s Day with a parade up Fifth Avenue starting at 40th Street, this was not always the way it was done. In fact, in the 19th century, the parade both began and ended in the East Village.

In 1870 the St. Patrick’s Parade began at the corner of Second Avenue and 10th Street, in front of St. Mark’s-in-the-Bowery (Episcopal) Church, and from there headed south down Second Avenue to City Hall. It then marched its way back uptown to Union Square, eventually ending in front of the Cooper Union at Astor Place and Cooper Square.

It followed this very convoluted route for years until the construction of the new St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Fifth Avenue and 50th Street, after which the parade began its current route up Fifth Avenue. At the time it was built, St. Patrick’s was, curiously, the only Catholic Cathedral built in New York State not designed by the Irish Catholic architect Patrick Charles Keely, but rather by Protestant James Renwick Jr., who descended from some of the oldest New York families of English and Dutch stock.

Oscar Wilde stayed at 48 West 11th Street in Greenwich Village during his first trip to the U.S. in 1882; Map data © 2019 Google

Writers

There’s no shortage of writers of Irish or Irish American extraction who in some way made their mark in Greenwich Village and the East Village. Just a small sampling includes Eugene O’Neill, who co-founded the Provincetown Playhouse Theatre at 133 MacDougal Street (a fragment of which has survived multiple demolitions and alterations by NYU); Oscar Wilde, who stayed at 48 West 11th Street in Greenwich Village during his first trip to American in 1882; James Joyce, whose scandalous and groundbreaking modernist retelling of The Odyssey Ulysses was first published in serialized form in Greenwich Village’s The Little Review magazine at 27 West 8th Street; New York School poet Frank O’Hara, who lived at both 441 East 9th Street in the East Village and 90 University Place in Greenwich Village; and Basketball Diaries author and post-punk musician Jim Carroll, who honed his craft at the St. Mark’s Poetry Project on East 10th Street, co-managed Andy Warhol’s porn theater at 62 East 4th Street, and after his death in 2009 had his wake at the Greenwich Village Funeral Home on Bleecker Street and his funeral at Our Lady of Pompeii Church on Carmine Street.

+++

This post comes from Village Preservation. Since 1980, Village Preservation has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid